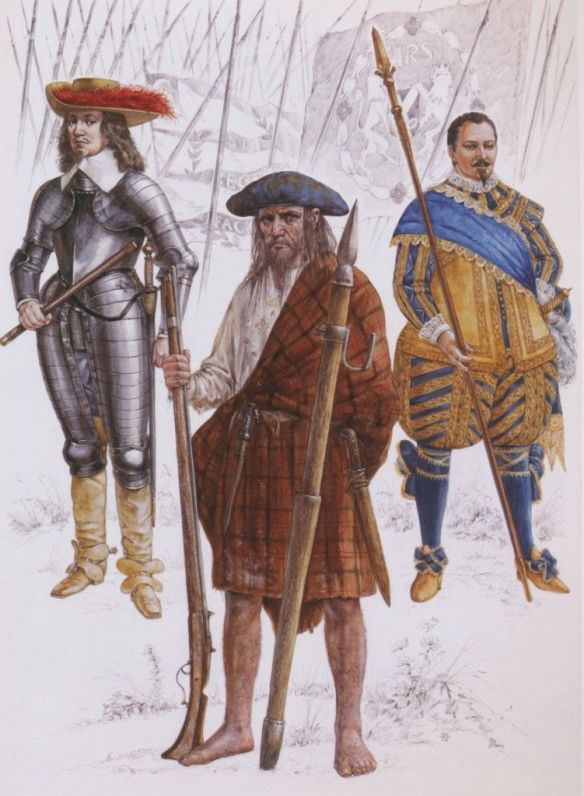

Scots in Swedish Thirty Years’ War service.

In October 1605, having embarked on his war with Poland in Livonia, Karl IX of Sweden sought Robert and James Spense assistance in the recruitment of soldiers. The use of merchants as middlemen or agents in recruitment was an established practice – they had contacts, access to transport and, most importantly, financial resources at their disposal. Recruitment also took place through the agency of military officers. Both merchants and officers were expected to carry out the task at their own expense against later reimbursement and employment. The king had already employed a Colonel Thomas Uggleby (Ogilvie) in 1602 to secure Scottish troops and in January 1607 Robert Kinnaird was sent from Sweden to the North-East, to the Gordon country, to raise 200 horsemen. Through Spens, Karl wanted 1,600 foot soldiers and 600 cavalry, a levy that had to be undertaken with the approval of the British monarch. James Spens’s reward would be the sum of 1,600 thaler for every 300 men and the rank of colonel in command of his recruits. It was an enticing prospect but the recruitment of such a large number of men presented Spens with considerable difficulties; after two years and no sign of them, Karl obviously began to wonder what was going on and, a few days after despatching Robert Kinnaird in 1607, wrote to Spens to express the hope that he would arrive in the spring with the troops. When May came and there was still no sign of soldiers, Karl had to send another letter, following it later in the year with similar ones to Thomas Karr and William Stewart. The latter styled himself ‘of Egilsay’ and was the brother of the Earl of Orkney. A 1609 commission from him to Captain John Urry appoints the latter to be in command of a company of 200 infantry in Karl’s service.

It is difficult to pin down how much a recruiter might hope to gain personally through his activities in raising men; some profit could be expected but this could be conceived as reward in the form of status or war plunder rather than in cash. The Swedish government between 1620 and 1630 laid down a rate for recruitment of 8 riksdaler per man, a sum that fell to 6 in 1631 and dropped to 4 in the following few years. As a riksdaler had an exchange value varying from 4 to 5 shillings sterling, the recruiter therefore could expect to have a sum of up to £2 per man to carry out what he had agreed to do. This sum included the provision of food and drink for recruits, probably some clothing too, and their transport costs across the North Sea, as well as a handout when a man signed on. In his study of recruitment for Sweden in the 1620s, J.A. Fallon calculated that it cost 6s 8d to ship a man from Scotland to the Elbe, and that two weeks’ food and drink for a recruit cost 9s 4d. Fallon suggested that 4s would have been handed to the newly signed-on recruit – hence the ‘dollar’ in the saying about the chief of Mackay. These expenses add up to £1. Fallon suggested that a recruiting captain might typically expect a payment of £1 per recruit. It is possible that the difference between the captain’s outlay and the overall sum afforded by the riksdaler–pound exchange rate went into the recruiting agent’s coffers, as we must accept that there would always have been the temptation among agents to minimise expenses and redirect a little cash into their own pockets. They also faced a fine if the numbers they attracted fell short of the total they had promised to bring in.

Spens was now running up against serious problems in fulfilling his side of the bargain with Karl IX, perhaps partly from difficulties with finance and shipping but also because James was loathe to allow so many men to go abroad to serve the Swedish flag, worried they might be deployed against his own brother-in-law, the King of Denmark. Karl IX sent a pair of falcons to James in August 1609 with a letter designed to allay the canny king’s suspicions, a gift the latter reciprocated with a book. To further Karl’s aims, Spens came over from Sweden in December 1609 with what amounted to a delegation of several Scottish officers that included Samuel Cockburn, who held the rank of colonel and had been in Swedish service since 1598.

The recruitment drive paid off at last but the numbers amounted to only a fraction of what Karl had first sought. Three hundred arrived in Sweden in January 1610, and further contingents were recruited in Ireland and England. In March 1610 the council noted a request from captains Johnne Borthuik and Andro Rentoun, who had received no reimbursement from Stockholm for the 4,000 merks and 300 riksdaler they had raised for the recruiting and shipping of men for Swedish service and who were now seeking the council to ask James to raise the matter with Karl on their behalf. The soldiers joined the Swedish forces in Russia, in time to be present at the defeat at Klushino on 4 July 1610 and were among the men who sat out the battle in response to the Polish commanders’ promises. James Spens, although nominally the senior officer, was not present in the field, and any blame, however slight, that may have come his way after the levies deserted to the Polish side did not prevent him from continuing a successful diplomatic career, not only as ambassador from the Stuart monarch to Sweden but also, at various times, to Denmark, the Dutch Republic, Danzig and Brandenburg.

Karl IX recaptured parts of Livonia during 1607 but in the spring of 1609 Chodkiwiecz began a campaign to strike at the enemy bridgeheads on the coast. An attempt to take Dynemunt at the mouth of the Dvina failed and he switched his attention to the port of Parnawa at the northern end of the Gulf of Riga, taking advantage of late-season frosts to ease movement through the swamps and forests. The defenders knew the enemy was at their door but remained unaware that the threat came from the main Polish–Lithuanian army and not bands of marauders. Chodkiwiecz ordered his men to the attack during the night of 16 March before Swedish reinforcements could arrive from Reval. In this battle Scots fought on both sides. On the Polish side were a company of Scottish mercenaries and 14 Scots sappers, while some 155 Scots under Captain John Clark were members of the Swedish garrison. Under fire the sappers, under the direction of two French engineers, managed to insert a bomb under the south gate of the town, which destroyed this section of the defences and allowed the Poles to burst in. The garrison retreated to the castle but after a short time surrendered. John Clark and his Scots then changed sides, a common practice during this period.

Chodkiwiecz’s and Karl’s armies marched and fought each other around the shores of the gulf during all 1609. Mansfeld, who had escaped from the catastrophe at Kircholm, returned to the fray at the head of an 8,000-strong army that included some Scots along with French, Swedish and Dutch. Riga and Parnawa endured sieges again as the combatants struggled for control of the lands around the gulf until, late in 1609, the Swedes were finally forced to surrender. By this time a former enemy of both sides had entered the contest: Russia.

A violent and confused struggle for power ensued in Russia after Ivan the Terrible’s death in 1584, a struggle out of which Boris Godunov emerged as victor and tsar in 1598. Among the Scots in his service were two captains, Robert Dunbar and David Gilbert, both of whom entered Russia in 1600 or 1601. Of Dunbar we know little beyond his name and rank. One historian described Gilbert as ‘an international scoundrel’, a judgement that could just as easily be ascribed to many mercenaries of his ilk. A challenge to Godunov’s regime emerged from Poland in 1601 in the person of a defrocked priest who claimed to be the grandson of Ivan. This man, who is known to history as the first False Dmitri, launched a campaign in the direction of Moscow with the support of some Poles and disaffected Russians. Gudonov’s army defeated Dmitri’s force but Gudonov himself died in April 1605, giving Dmitri and the rebellious boyars a second chance to seize power. At this time David Gilbert was serving as a member of Dmitri’s bodyguard, a unit made up entirely of foreign mercenaries, some three hundred English, French and Scots, deemed more trustworthy than native Russians. Moscow now entered a phase in its history remembered as the Time of Troubles. Dmitri himself was assassinated by boyars less than a year after his coronation, and the crown was awarded to Vasily Szujski. This new tsar was equally unable to bring order out of the Russian chaos and he too was challenged by rebels who gathered under the banner of another pretender, the second False Dmitri. Meanwhile Gilbert appears to have returned to Scotland, as in July 1607 the Privy Council granted a warrant to a man of his name as one ‘being laitlie imployit be the king of Swadene to levey and tak up ane company of gentilmen to pas to Swadane’. The company sailed from Leith that summer. Among them was a man called Robert Carr, a consummate horseman and possibly from the Borders. Back in Russia in 1608, possibly through a transfer of allegiance of the first Dmitri’s bodyguard when his Polish widow, Marina Mniszek, married the second Dmitri, David Gilbert found himself in the retinue of the latter and, before long, charged with treason. Perhaps this had something to do with the Swedish connection in the Privy Council minute. Only the intercession of the Polish wife saved Gilbert from a judicial drowning in the River Oka to the south-east of Moscow. After this narrow brush with Russian justice, Gilbert clearly thought it was time to make himself scarce and switched his allegiance to Poland.

The Time of Troubles tempted Russia’s neighbours to interfere in her affairs. Mercenaries also smelled an opportunity and several Scots officers in command of Germans passed east through Prussia, pillaging the country there. In February 1609 Vasily Szujski formed an alliance with Sweden, and in response the Polish king, Sigismund Vasa, sent his army into Russian territory to begin a siege of Smolensk in September. Surrounded by the pine forests from whose resin it takes its name, Smolensk marked the highest navigable point on the Dnieper River and the site of the portage to the Dvina and the Baltic. Strongly defended and well supplied, it held out over the winter, tying down the Commonwealth forces before its walls.

Vasily mobilised his army to relieve the city on the western fringes of his realm, and Karl IX lent him Swedish troops under the command of Jacob de la Gardie, the son of the commander with the first name of Pontus at Wesenberg. The combined Swedish–Russian army advanced towards Smolensk in the summer of 1610. Sigismund Vasa learned of the approaching enemy through a group of disaffected Russian boyars and, on 6 June, a section of the Commonwealth army was detached under the command of Hetman Stanislaw Zolkiewski to intercept them. Although Zolkiewski’s force was heavily outnumbered, he held the advantage of surprise and at dawn on 24 June his men swooped to entrap 8,000 Russians in the village of Carowa-Zajmiszcze. Leaving enough troops to convince the Russians they were still surrounded, he led most of his force on a two-day march through wet weather to meet the main body of Vasily’s army. Zolkiewski now learned that there was dissension in the Russian camp between the native troops and the mercenaries and cleverly exploited this by letting the latter know through his network of agents that he was offering the foreign soldiers a bounty and a safe passage home for not fighting. De la Gardie discovered the subterfuge and quelled any mutiny but the seeds of temptation had been sown among the discontented mercenaries.

The two armies almost blundered past each other. Zolkiewski’s troops moving through the forests in the night found themselves near the enemy but were not ready to give battle and were unable to take advantage of the surprise encounter. Vasily now deployed his army in entrenched positions on open ground near the village of Klushino, between the forest and a river. The Swedes and Russians, including the mercenaries under de la Gardie, numbered 35,000, the Commonwealth troops less than 7,000. Nevertheless, Zolkiewski attacked, sending in his waves of hussars with lances and flaming torches before dawn on 4 July. Time and again the Polish cavalry hurled themselves with pistol, carbine and lance against the Russians, who defended well until a Russian cavalry counterattack failed and melted into a confused retreat that spread panic among the other Russian ranks. Robert Carr was riding with the Swedish–Russian horse, but we do not know if he took part in this key moment in the struggle. A rout ensued, with the Polish cavalry chasing and cutting down the fleeing enemy. De la Gardie’s mercenaries, deployed on the left of the Russian front line in strong redoubts, conducted themselves well, but they were weakened by dissension. One report, by Zolkiewski himself, states that the Scots and English among them chose not to fight and remained in their camp in the forest until they could surrender to the Commonwealth troops. These men agreed either to join the enemy or go home after pledging not to take up arms against the Commonwealth again. Carr returned to England in 1619 but it has been suggested he went back to Russia and founded a family with the surname of Kar.

In the wake of his defeat in the field, Vasily was overthrown. The way was now open for the Poles to occupy Moscow and they stayed in the Kremlin for the next two years. Smolensk also fell after a long siege. The Polish occupation was brought to an end by the emergence of a strong leader among the Russians; Mikhail Romanov was only sixteen years old when he was elected tsar in 1613 but he proved himself capable of regaining the lost territories. Gilbert campaigned with the Polish army in Russian territory but unfortunately fell into enemy hands and was taken back to Moscow, where he languished in fetters for three years. Again he escaped capital punishment when Sir John Merrick, ambassador to Tsar Mikhail from James VI, successfully interceded for his life. One may have forgiven Gilbert for concluding he had seen enough of Russia but, in 1618, with one of his sons, he returned and probably died there. Tsar Mikhail proved to be as fond of employing mercenaries as his predecessors had been: during his rule the number of foreign officers in Russian service rose to over four hundred, presenting the Scots with more opportunities to find service on the distant fringes of Europe.