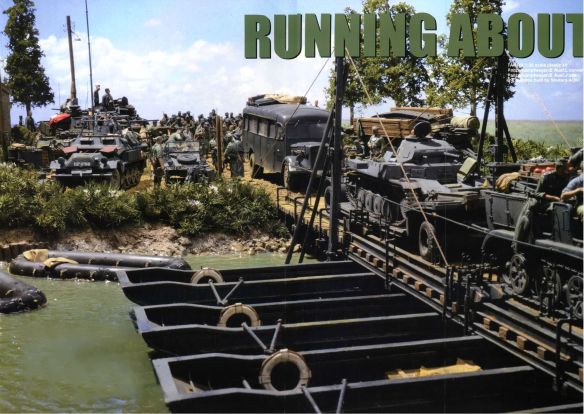

The geography of the Axis–Soviet borderlands was defined in great part by the numerous rivers, particularly the Bug and the Dniester that faced AGS and AGC respectively. Elements of AGN would have to cross the Niemen River followed by the Dvina and the Lovat, the spaces between which were cut by smaller rivers and tributaries. In many areas the approaches were swampy and the bridges few and far between and frequently incapable of sustaining more than light vehicles. Therefore, the fighting would be dominated by both sides attempting to take or hold bridging points. To further complicate the issue vast swathes of the western USSR was heavily forested, remaining what it had been for thousands of years – a primeval wilderness. Many of the waterways were well over 100m wide and certainly during the early weeks of the Barbarossa campaign swollen by heavy rainfall. AGC faced the additional problem of its invasion route being split in two by the soaking morass known as the Pripet Marshes.

The armoured spearheads of AGC, Second and Third Panzer groups (Generals Hoth and Guderian respectively), would confront these problems from the very first day. Indeed, Hoth’s forces had to deal with three rivers within 60km of their ‘dry’ border crossing. Second Panzer Group crossed the Bug River in the vicinity of Brest-Litovsk Fortress on bridges captured by Russian-speaking special forces troops of Regiment 800 – the Brandenburgers. These specialists in infiltration and sabotage were also largely responsible for widespread disruption of the Soviet communications system by the simple expedient of cutting the wires of the civilian network. Radios were in short supply and consequently the Red Army depended on civilian landlines. Furthermore, when radios were available their operators were frequently jammed and continually monitored. A commonly intercepted message within the first 24 hours of the invasion was, ‘The Germans are attacking what shall I do?’

By 1500hr on 22 June, Barbarossatag, units of Second Panzer Group had bypassed Brest Fortress and were into open country. Third Panzer Group, crossing all three rivers by captured bridges, were within 48 hours responsible for breaking the connection between the NW and W fronts where the Eleventh and Third armies linked. With his communications with Third and Fourth armies in chaos, the W Front’s commander, General D.G. Pavlov, could only guess at what was going on. It seemed that his Tenth Army in the centre of the front was the only unit holding together. In an attempt to restore contact with the NW Front, Pavlov ordered a counterattack in the direction of Grodno.

The operation was to be led by General I.V. Boldin, the W Front’s second-in-command, and involved VI Mechanized and VI Cavalry corps from Tenth Army and XI Mechanized Corps from Third Army. The mechanized corps each had 2 tank divisions, totalling some 1,000 armoured vehicles. A formidable force, it included over 200 T-34 and KV-1 tanks. Despite the numbers, it was German experience that told and the attack failed and Grodno was lost. On 25 June Moscow ordered the W Front to fall back to a line running north to south from Lida–Slonim–Pinsk on the edge of the Pripet Marshes. Unfortunately for Pavlov, Hoth’s armour was already on the way to Minsk via Vilnius, which had fallen on 24 June. To the south Second Panzer Group, having destroyed 95 per cent of XIV Mechanized Corps’s 480 tanks, was well on its way to Baranovichi.

Moscow’s next instruction to Pavlov was to ‘achieve positive control over front line units’ and to ‘evacuate Minsk and Bobruisk’ to the south west. But by this time most of the W Front’s original forces were being contained in what became known as the Minsk Pocket. The German term for this technique is kessel, which translates as cauldron and this is the term that will be used in this book.

Minsk, capital of the Belorussian SSR, had already witnessed the evacuation of the Communist Party’s officials. Martial Law had been declared in the western and southern districts of the USSR on 22 June and the evacuation of officials and state property from Minsk began three days later in the face of Third Panzer Group’s rapid advance. In the process of this Hoth’s forces were passing through the fixed defence line of the 1920s and 1930s. Line is a misnomer, conjuring as it does the impression of fortifications similar to those of the Maginot Line. The so-called Stalin Line was neither continuous nor in many places was it anything other than a set of blueprints. It had been conceived as a series of fortified zones covering river crossings and other points of strategic value from the 1920s when the border ran along the Estonian, Latvian, Lithuanian, Polish and Romanian frontiers. To cover the designated areas hundreds of concrete machine-gun and field-gun bunkers were built between 1928 and 1939. When the frontiers moved westwards another series of fortified zones was planned – the so-called Molotov Line. Such engineering works were expensive in terms of time, money, resources and manpower. Furthermore, prioritizing which to build varied with the prevailing political mood. Weapons allocation was transferred to the Molotov Line so that many assets were shipped from the Stalin to the Molotov Line. A case of robbing Joseph to pay Vyacheslav.

Consequently, the invaders were faced with a patchwork of fortifications, some tough and viable, others simply holes in the ground. Manning these systems fell to the remnants of first-line units, reserves and local militia, few of which had the specialist training required to carry out such work.

With Guderian reluctantly closing on Minsk from the south and Hoth moving more eagerly from the north, Pavlov ordered the recently raised Thirteenth Army to hold the Minsk Fortified Region. On 29 June the city was surrounded and Belorussia lost, and 24 hours later Pavlov was relieved of command of the W Front and replaced by Marshal S.K. Timoshenko. Simultaneously, OKH (Oberkommando der Heeres (German Army Supreme High Command)) ordered von Bock’s AGC to align his forces for ‘operations in the direction of Smolensk’. OKH was, until late 1941, subject to control from the OKW (Oberkommando der Wehrmacht which directed army, air force and navy operations). When Hitler took leadership of the OKH, in December 1941, it effectively became independent of OKW. As AGC regrouped, Hitler and his staff had to decide what their course of action would be – where would von Bock’s armour go next?

AGN’s left flank rested on the Baltic Sea and was the responsibility of General von Kuchler’s Eighteenth Army. In the middle of AGN General Hoepner commanded Fourth Panzer Group and on the right flank Sixteenth Army, led by General Busch, was tasked with maintaining the connection with AGC. AGN was commanded by Field Marshal von Leeb. Fourth Panzer Group was expected to secure the river crossings and made a mixed start. By 23 June one crossing over the Dubysa River by 1st Panzer Division had been taken but 6th Panzer Division failed in similar missions because of a shortage of fuel brought on by the heavy going. It was then attacked by strong Soviet armoured units. For 24 hours battle raged at close quarters as 1st Panzer Division fought through to relieve its sister unit. Eventually, with constant support from Fliegerkorps 1, the tables were turned and the Soviet attackers were thrown back with losses of 90 per cent in men and machines. With much of the Soviet tank force thus eliminated, the panzers were free to resume their missions. General Manstein, commanding LVI Panzer Corps (8th Panzer and 3rd Motorized infantry divisions) was in the happy position of exploiting the gap created by Hoth’s Third Panzer Group when they pushed the NW Front’s Eleventh Army east instead of north. Now the race was on to capture the vital Dvina River bridges at Dunaberg. General F.I. Kuznetsov, commanding the NW Front, recognized the threat and committed the newly raise Twenty-Seventh Army, composed entirely of infantry but supported by XXI Mechanized Corps, to make for Dunaberg. However, locally conscripted militia were unable to prevent the city’s bridges and fortifications from being captured. As elsewhere in the Baltic States, natives took up arms to attack what they regarded as Russian occupation forces.

Stavka had ordered Kuznetsov to hold the Dvina River line but, despite counterattacking valiantly, he had signally failed to do so. Incredibly, he instructed Twenty-Seventh Army to fall back to the east and thus opened the road to Leningrad! As the men of Eleventh and Twenty-Seventh armies retired they began to reach parts of the Stalin Line which Kuznetsov had been told to hold. General N.F. Vatutin was ordered to join Kuznetsov as Chief-of-Staff with an instruction directly from Stalin to halt the Germans ‘at all costs’.

On AGN’s left Sixteenth Army made rapid progress across Lithuania and in ten days had covered some 120km, crossed the Dvina River, captured Riga and proclaimed a Latvian Provisional Government. Cheered on by the Lithuanians and Latvians, the operation to date had seemed to some ‘like an exercise.’ However, despite almost cornering Eighth Army, its infantry had been unable to effect an encirclement and the Soviet troops fought on doggedly.

Away on the right flank the forward elements of General Busch’s Sixteenth Army had reached the capital of Lithuania, Kaunas, which had already been liberated by local forces. The newly formed Lithuanian Provisional Government took office in the capital on 23 June. However, they were too late to save the bridges over the Niemen River and its tributaries. Supported by local forces, 121st Infantry Division held off several Red Army counterattacks to occupy the city. With Kaunas secure, Sixteenth Army’s infantry set off in the wake of the panzers in an east–north–easterly direction. As they advanced there were increasingly numerous and worrying reports of attacks by roving groups of Russian stragglers on their dramatically stretched supply lines. To counter this threat unofficially raised units of Lithuanians and Latvians were permitted to carry out security duties, a task that they undertook with relish and often little mercy.

But now it was von Leeb’s turn to commit errors which would gift his opponents time to prepare defensive lines before Leningrad and realign their battered forces. Hoepner’s panzer group was ordered to halt along the Dvina River and await the arrival of Sixteenth Army, which took until 4 July. To compound matters von Leeb did not unite his armour into one mass but instead he prevaricated and lost more precious time. In his defence Fourth Panzer Group was a precious asset not to be committed recklessly to battle in the vast, dank, brooding forests in front of Leningrad unless it enjoyed the close support of infantry. As Sixteenth Army fell in along the Dvina River and its supply columns pushed ahead as fast as they could, Stalin wasted little time.

The N Front’s troops in and around Leningrad were to create a defensive line along the Luga River from the coastal city of Narva to Lake I’lmen. This cobbled together force was to be known as the Luga Operational Group (LOG). Behind the Luga Line a series of defence lines were to be put in place with the final section covering suburban Leningrad. The people of the former capital were mobilized to dig and the fit and able to fight.

As well as noting the defensive preparations German intelligence also observed the build-up of Soviet forces in the Velki Luki area, which posed a threat to the junction of AGN and AGC. Leningrad was not about to be abandoned to the invaders without a fight.

Far away to the south Field Marshal von Rundstedt’s Army Group South’s Brandenburg Special Forces failed to take the bridge over the San River until late on 22 June. III Panzer Corps, part of First Panzer Group, broke through Soviet infantry positions and was en route for Lutsk, an important road and rail hub on the Styr River. It was taken on 25 June. To the south infantry of General Kempf’s XLVIII Panzer Corps opened the way for 11th Panzer Division to advance on Dubno. To interdict this movement General M.P. Kirponos, commanding the SW Front, set several of his mechanized corps in motion to counterattack. IV and XV Mechanized corps were both bloodily repulsed, while others, having endured a gruelling march of up to 75km under almost continual Luftwaffe attack, arrived with their numbers significantly depleted. 13th Panzer Division had little difficulty in fending off their poorly coordinated attacks. Elsewhere, however, it was a very different story. XV and VIII Mechanized corps had nearly surrounded 11th Panzer Division until the jaws of the encirclement were torn apart by 16th Panzer Division. Sensibly, Kirponos withdrew his armoured units on 27 June before the losses became too great. Despite this prudent move, a gap was now developing between Fifth and Sixth armies which First Panzer Group was about to exploit.

As Fifth Army retired to the southern reaches of the Pripet Marshes Sixth Army prepared to defend Lvov. At his HQ von Rundstedt was concerned that AGS’s right flank, Seventeenth Army, was moving too slowly and exposing other forces to Soviet penetration from the south. Anxiously, von Rundstedt awaited Hungarian and Romanian intervention. While considering how best to encircle Lvov, von Rundstedt received news that 9th Panzer Division was to the rear of the city and the Soviets were hurrying to leave.

Covered by a succession of rearguard actions, the SW Front fell back in relatively good order towards the Stalin Line. On 2 July Hungarian forces crossed the Dniester River and Seventeenth Army broke the connection between Kirponos’s Sixth and Twenty-Sixth armies. However, as AGS advanced its frontage increased, as did that of the Soviets just as they began to lose their cohesion. Now moving into more open country, von Kleist’s armour was able to pursue its opponents with greater effect. Once again the defences that stood before the Axis troops were a mixed collection of useful and useless, manned in many cases by reservists with little or no idea how to make use of what weapons they held.

Operation Munich was the code name for Romania’s invasion of the USSR by which it hoped to reintegrate the lost province of Moldavia. German elements of Eleventh Army took a major bridge spanning the Prut River on 30 June, but the main blow came on 2 July with an attempt to split Eighteenth and Ninth Soviet armies. Eleventh Army was sandwiched between Third and Fourth Romanian armies to the north and south respectively. The attack was preempted by General I.V. Tyulenev’s blow at the junction of Fourth and Eleventh armies. German support for the Romanians was swiftly provided and the S Front, weakened by transfers elsewhere, was ordered to withdraw and re-assemble near Uman, roughly 120km to the north east. Initially, von Schobert moved, utilizing the recently arrived Italian CSIR, to encircle S Front between the Bug and Dniester rivers. Crossing the latter between 17 and 21 July, a combination of unseasonably bad weather and recently introduced Soviet scorched earth tactics allowed the S Front’s forces to escape.

The SW and S fronts had achieved some success in holding up AGS’s progress, indeed considerably more than W or NW fronts had, but both were now starting to suffer from the same symptoms of impending doom already experienced by the W Front. Communications were disintegrating and there was very little left to defend before the Dnieper River and the Ukrainian capital of Kiev aside from the rolling steppe. Kirponos’s front slowly but surely began to unravel. By mid-July Fifth Army was holding out on the southern edge of the Pripet Marshes, while Sixth and Twelfth armies gravitated towards the S Front’s operational area.

Much as was the case with AGN, Hitler wanted to use the panzers of AGS to do more including the capture of Kiev while von Rundstedt wished to leave Kiev to the infantry of Sixth Army. But now the flanks of the latter were receiving the attention of Fifth Army. On 4 July elements of Kleist’s First Panzer Group had broken into the Stalin Line at Novgorod-Volynski, 250km west of Kiev. 13th Panzer Division took Berdichev three days later and on 9 July Zhitomir fell and III Panzer Corps was ordered to take Kiev. This was in line with the Führer’s wishes but he wanted part of Kleist’s armour to participate in an encirclement of Soviet forces in the Dnieper River bend to the south of Kiev. This topic became the subject of much debate but before a conclusion was reached 13th Panzer Division had crossed the Irpen River and was within 25km of the Ukrainian capital. The appearance of German tanks that close to Kiev horrified the Soviets. Stalin ordered an immediate series of counterattacks by the S and SW fronts. These desperate efforts were poorly coordinated and costly both in terms of men and materiel. The German armoured formations held on desperately as infantry, both motorized and on foot, was rushed to their aid. By 19 July von Stulpnagel’s Seventeenth Army was coming up and it was decided to use nine of its infantry divisions to replace I Panzer Corps, which would now combine with other infantry divisions to encircle Soviet troops in the Uman area. Satisfied that he had blunted the German attack, Kirponos was unaware that it was elsewhere along the Eastern Front that the stage was being set for an even greater disaster than those that had already overtaken the Red Army.