In late September 1944 the Allies became aware that Hitler was withdrawing his armour from the front in order to build up a very large panzer reserve. Alarmingly his tank strength on the Western Front steadily expanded to 2,600 tanks compared to 1,500 on the Eastern Front. Signals intelligence indicated that the 1st SS, 2nd SS, 9th SS and 12th SS Panzer divisions, along with the 17th SS Panzergrenadier division, were being refitted for renewed combat. Most notably, the two SS Panzer Corps were swiftly rebuilt as the strike force of SS-Oberstgruppenführer ‘Sepp’ Dietrich’s powerful 6th SS Panzer Army. The 6th Panzer Army is best noted for its leading role in the Battle of the Bulge (December 16, 1944 – January 25, 1945). On April 2, 1945, it was transferred to the Waffen-SS. The 6th Panzer Army then became known as 6th SS Panzer Army (6. SS-Panzerarmee).

Although it didn’t receive the SS designation until after the Battle of the Bulge, the SS designation came into general use in military history literature after the Second World War for the formation as assembled prior to that campaign. After the Ardennes Offensive, the 6th SS Panzer Army was transferred to Hungary, where it fought against the advancing Soviet Army.

The two panzer divisions of SS-Gruppenführer Hermann Priess’ 1st SS Panzer Corps were each brought up to about 22,000 men; the 1st SS Panzer division was supplemented with Tiger tanks of SS Heavy Panzer Battalion 502; and the 12th SS, now under SS-Brigadeführer Hugo Krass, was rebuilt, though it lacked experienced junior officers. The 2nd SS, reassigned to SS-Gruppenführer Heinz Lammerding, and the 9th SS, reassigned to SS-Brigadeführer Sylvester Stadler, of SS-Obergruppenführer willi Bittrich’s 2nd SS Panzer Corps were similarly rebuilt with better than average recruits, though the 9th SS lacked transport.

Up until the end of the year the 2nd SS and 10th SS Panzer divisions helped hold the Siegfried Line while Hitler built up his counter-attack force for the Ardennes offensive, which had been in preparation from October. This was initially codenamed watch on the Rhine (Wacht am Rhein) to imply a purely defensive operation, but subsequently became Autumn Mist (Herbstnebel). Planning was entrusted to Field Marshal Model’s Army Group B and he was allocated the very last of Germany’s reserves – some ten panzer and fourteen infantry divisions.

After three months the Americans had been unable to punch through the Siegfried Line between Geilenkirchen and Aachen. on 12/13 November the weak 17th SS and 21st Panzer divisions counter-attacked at Sanry-sur-nied, driving the Americans back, although they were forced to withdraw for fear of encirclement. The 17th SS was ordered to retreat and escaped being trapped in Metz, which finally fell on 17 November. By the beginning of December the division was down to just 4,000 men and twenty tanks and was no longer available for the Ardennes offensive.

Hitler’s massed armed forces included Dietrich’s 6th SS Panzer Army, with the 1st SS, 2nd SS, 9th SS and 12th SS Panzer divisions, 501 and 506 Heavy Panzer Battalions, plus seven army divisions equipped with a total of 450 tanks, assault guns and self-propelled guns; von Manteuffel’s 5th Panzer Army with nine divisions included about 350 armoured fighting vehicles. The 7th Army, with a similar number of divisions under General Erich Brandenberger, had a few battalions of tanks and assault guns. Antwerp was their goal; 6th SS Panzer Army was to break out between Liège and Aachen and 5th Panzer Army between Namur and Liège.

In the past Himmler had accepted SS divisions coming under army corps commanders and SS army corps and SS armoured groups coming under army commanders, but the Ardennes was a subordination of a completely different magnitude. For the first time a whole army was placed under the command of an SS general with the minority of his command consisting of SS units. This general, though, was under an army field marshal. Furthermore, the Waffen-SS was completely reliant on the army’s newly raised Volksgrenadier divisions and Luftwaffe parachute units fighting as infantry to first seize the ground over which their panzers were to advance.

On 10 December 1944 Hitler found a convenient way to avoid Himmler being involved in the forthcoming Ardennes offensive. The Reichsführer-SS was appointed commander-in-chief of Army Group Upper Rhine, far from the centre of action. This meant he could not meddle in Field Marshal von Rundstedt’s control of the 6th SS Panzer Army. Rundstedt as C-in-C west had been particularly irked by Himmler styling himself ‘Supreme Commander, Westmark’. It also forced Himmler to commit his replacement Army to the front; in particular, he plugged a gap in the defences of the German frontier south of Karlsruhe, which was independent of Rundstedt’s command.

Although the Ardennes was the first time an SS army took to the field, only four of ‘Sepp’ Dietrich’s six panzer divisions actually belonged to the Waffen-SS and two of them were soon detached from the right flank to bolster the 15th Army; they were replaced by the inadequate Volksgrenadier divisions of Himmler’s replacement Army. Dietrich, who nominally answered to von Rundstedt, was flabbergasted at the scope of the proposed operation:

Reach the Meuse in two days, cross it, take Brussels, go on and then take Antwerp? Simple. As if my tanks could advance in a bog. And this little programme is to be executed in the depths of winter in a region where there are nine chances out of ten that we will have snow up to our middles. do you call that serious?

He hoped to reason with Hitler but the Führer would not see him. Dietrich was acutely aware that although the SS panzer divisions had been rebuilt, they were not what they had once been, bitterly observing: ‘out of all the original Adolf Hitler division there are only thirty men today who are not dead or prisoners. Now I have recreated a new panzer army and I am a general and not an undertaker.’

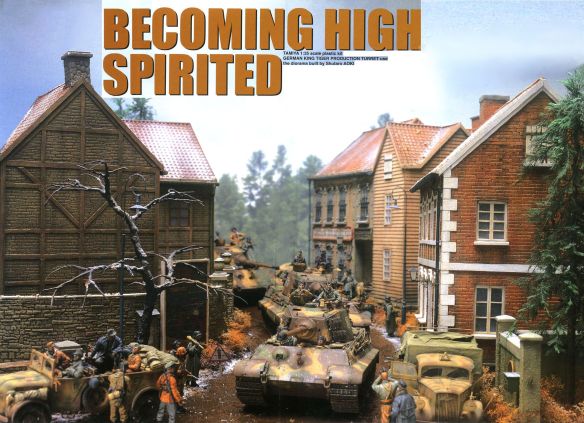

Perhaps not surprisingly after its losses in Normandy, the 12th SS was only able to field one mixed tank battalion for the Ardennes offensive, consisting of two companies of Panzer IVs and two companies of Panthers. The other battalion remained in Germany, where it was being reconstituted. The division also committed its two panzergrenadier regiments and its anti-tank battalion. Kampfgruppe Peiper, drawn from the 1st SS, consisted of a hundred Panzer IVs and Panthers, forty-two formidable King Tigers and twenty-five assault guns.

Elements of the 1st SS and 12th SS Panzer divisions conducted the 6th SS Panzer Army’s main attacks to the north along the line St Vith–Vielsalm on 16 December 1944. They did so under dense cloud, thereby avoiding the unwanted attentions of the Allies’ troublesome fighter-bombers.

Unfortunately for Dietrich, SS-Obersturmbannführer Peiper, whose forces were desperately short of fuel, turned north to seize 50,000 gallons of American gasoline at Bullingen, instead of pushing west. His force was eventually surrounded and destroyed, leaving forty-five tanks and sixty self-propelled guns north of the Ambleve River.

The 12th SS, following-up the Kampfgruppe, was unable to dislodge the Americans from the Elsenborn ridge and had to swing left, nor was Panzer Lehr able to get to Bastogne before the Americans reinforced the town. on the northern shoulder of the advance the 9th SS headed northward after breaking through the Losheim Gap; frustratingly only the artillery regiment and reconnaissance battalion were committed, although once St Vith was captured the rest of the division was brought in. On 18 December the troops of the 9th SS reached their official start line and fought their way towards Manhay and Trois Ponts before being replaced by the 12th Volksgrenadier division. They got as far as Salmchateau, less than halfway to the Meuse.

Meanwhile 116th Panzer drove between Bastogne and St Vith, but the Americans holding out in Bastogne delayed 2nd Panzer. Crucially, the failure to take Bastogne greatly slowed Manteufell’s drive on the Meuse. St Vith fell on 21 December, though American artillery fire forced the 6th SS Panzer Army to become entangled with the 5th Panzer Army. Hitler felt that even if Antwerp were not taken, keeping his panzers in the hard-won bulge created in the front line would slow the Allies’ push on the vital Ruhr. To secure the bulge, Bastogne had to be taken and the 12th SS was shifted south to help capture the town.

By 22 December the 9th SS had been committed to the southern flank of the 1st SS, but could not reach Kampfgruppe Peiper. At the end of the month the 9th SS was replaced by the 12th Infantry division and also moved south to help with the assault on Bastogne. However, once the weather cleared Allied fighter-bombers began to attack the exposed panzers in a repeat of the Falaise battle. Exposed on the snow-covered landscape, many were easy targets. Lacking fuel, 2nd Panzer got as far as Celles, just 4 miles short of the river Meuse, before American armour moved in. American tanks also halted the 2nd SS, while 116th and Panzer Lehr were stopped short of Marche.

Even in the face of defeat, the 2nd SS continued to inflict heavy losses on the Americans. Normandy survivor Untersturmführer Fritz Langanke took his Panther tank into battle just before Christmas:

Thanks to our preparations, we knocked out the first five Sherman tanks in quick succession, despite the poor visibility. They moved at a steep angle to us, down the slope, half-right. The firing distance between us was 500 and 700 metres. The other tanks then turned around and drove back. Thereafter it was quiet and dusk set in soon.

The US 6th Armored division launched an attack near Bastogne on 2 January 1945. Although the tanks were driven off, American infantry broke through the positions of the 26th Volksgrenadier division, reaching Michamps. Under Normandy survivor von Ribbentrop, the 12th SS Escort company and the 1st Battalion, SS Panzer regiment 12, were sent to counter-attack. They recaptured Michamps and Obourcy, and along with the fighting at Arlencourt the 12th SS accounted for twenty-four American tanks. The 12th SS was then thrown at the northeast outskirts of Bastogne on the 4th, but the Americans turned back every attack. Shortly afterwards the 12th SS was withdrawn to Cologne. By now the 9th and 12th SS Panzer divisions only had fifty-five tanks left between them.

During the New Year Dietrich was dismayed that his SS panzer divisions had been handed over to the army to help take Bastogne. First Leibstandarte then the whole of the 1st SS Panzer Corps were assigned to Manteuffel. By 4 January Hohenstaufen had also been reassigned, leaving Dietrich with just Das Reich as his sole armoured unit. within four days both generals were in full retreat, heading back to their start line. Rundstedt counselled Hitler to withdraw the two battered panzer armies east of Bastogne ready for the inevitable Allied counter-attack. On 8 January Hitler finally ordered a partial withdrawal. The 6th SS Panzer Army was now needed on the eastern Front following a major Soviet offensive.

Meanwhile Himmler, with his first combat command, wanted to launch a major offensive across the Rhine. In order to distract attention from the Ardennes, he conducted operation Northwind (Nordwind) to the south in Alsace, involving ten divisions, including the Normandy veterans 10th SS Panzer and 17th SS Panzergrenadier on 31 December. It was simply too late to have any bearing on the fighting in the Ardennes.

Undoubtedly for Himmler this was a matter of SS prestige over the army. While the Army High Command had floundered on the Ardennes battlefield, Himmler believed he could be the conqueror of Alsace if he could retake Strasbourg. He wanted to be the civilian who had won a victory defending Germany while the army had failed. This conveniently avoided the embarrassing truth that ‘Sepp’ Dietrich and the 6th SS Panzer Army had also failed, even if it had been under the direction of the army.

Himmler’s planning was flawed from the start, because his offensive was to comprise three generally unrelated local offensives that could be contained piecemeal. His SS staff dominating Army Group Upper Rhine proposed a swift advance to the Saverne Gap by three panzer divisions, including the 10th SS supported by Volksgrenadier divisions to the north and south. This would cut the US 7th Army in two, the southern portion of which would then be destroyed, allowing Himmler’s offensive to sweep the French Army out of Strasbourg.

Along with the 36th Volksgrenadier division, the 17th SS Panzergrenadiers attacked the US 44th and 100th Infantry divisions near Rimlingen on 1 January 1945. within a week they had been thrown back and the Americans recaptured Rimlingen on the 13th. It was only after the Americans had withdrawn in good order towards the river Moder south of the Forêt de Haguenau that Himmler launched his secondary attacks in the centre around Gambsheim and to the south around Erstein.

The 10th SS achieved some success in its attack from Offendorf to Herlisheim on 17 January. Although this lost momentum, Obersturmführer Bachmann, adjutant of the 1st Battalion, SS Panzer regiment 10, remembered:

Everything went according to plan. The two-panzer crew cooperated in a first-rate fashion. Panzer 2 opened fire while Panzer 1 raced into the junction and knocked out the first Sherman. More US tanks were knocked out, and a white flag appeared….

The total was twelve captured Sherman tanks and sixty prisoners. I deployed my own two Panthers forward to the edge of Herlisheim. From there they covered in the direction of Drusenheim and knocked out two Shermans on their way to Herlisheim. Thus my two Panthers achieved nine kills.

Bachmann’s tanks crews were rewarded with Iron Crosses, with Bachmann himself gaining the Knight’s Cross. This success posed a threat to Strasbourg, forcing the Allies to counter-attack and clear the Germans from the west bank of the Rhine. Although Himmler’s Operation Northwind caused a small crisis for the Allies, it also wasted away Hitler’s already meagre reserves.

By the end of January, Hitler’s Ardennes bulge had gone for the loss of 100,000 casualties and most of their armour; the 5th Panzer Army and the 6th SS Panzer Army lost up to 600 tanks. Hitler’s great gamble had not paid off, although in five weeks of fighting twenty-seven American divisions suffered 59,000 casualties thanks to his reconstituted panzer divisions.

However, Hitler had achieved what Falaise had failed to do: the near-total destruction of the panzer forces in the west. This time there could be no miraculous recovery. Rundstedt did all he could to make the Waffen-SS shoulder the blame for the failure of the Ardennes offensive: ‘I received few reports from “Sepp” Dietrich of the 6th [SS] Panzer Army and what I did receive was generally a pack of lies. If the SS had any problems, they reported them directly to the Führer.’

In late January 1945 Himmler was posted to the Eastern Front to command Army Group Vistula. General Westphal, one of Himmler’s bitterest critics, regarded his organisational abilities as a shambles. Upon Himmler’s departure, ‘There was naturally no question of an orderly transfer,’ wrote Westphal, as the Reichsführer-SS left behind ‘a laundry-basket full of unsorted orders and reports.’

Paul Hausser assumed command of the Upper Rhine, which came under Rundstedt as C-in-C west. Hausser found himself with the unenviable task of holding the Colmar pocket with much-depleted forces. Himmler took with him General Lammerding as his Chief of Staff. Lammerding, former commander of the 2nd SS Das Reich, had blood of the Oradour-sur-Glane massacre and the Tulle executions on his hands. Himmler did not care.

This footage, taken by an SS war correspondent shows the lead elements of Kampfgruppe Peiper’s heavy tank battalion moving through the town of Tondorf on the afternoon of Dec. 16, 1944.