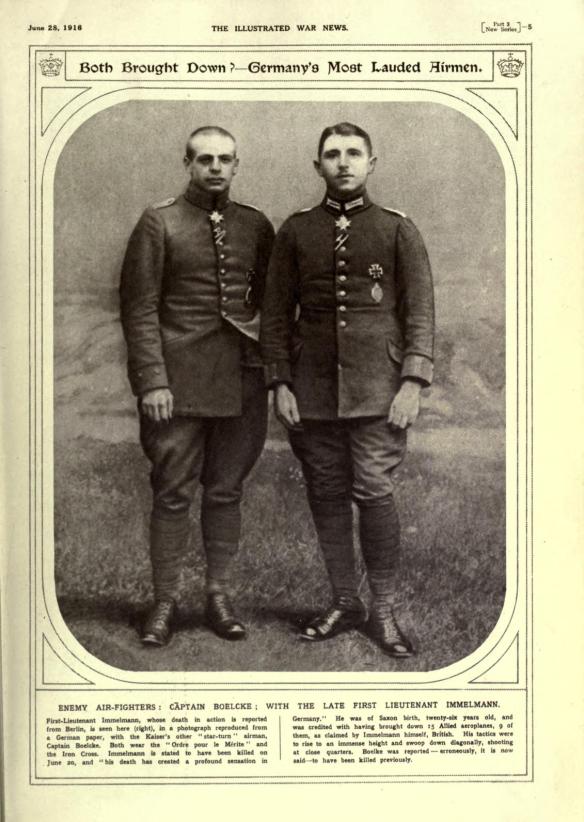

Bavaria, though part of the Kaiser’s Reich, had a strong tradition of independence. It was the South German wing of the air service which formed the first three bespoke (if ad hoc) fighter groups, latterly the brilliantly named Kampfeinsitzer-kommando or KEK, combat single-seater commands. This facilitated the rise of two men who were to symbolise the emerging cult of fighter aces – Max Immelmann and Oswald Boelcke. In January 1916 both would be awarded the Pour le Mérite – the legendary ‘Blue Max’; Germany’s highest gallantry award. For an ace, it was the badge of stardom. Celebrity was becoming important. Propagandists on both sides realised that these heroic lone wolves offered the cloak of chivalric glamour in this most un-chivalrous of wars. It was on that day perhaps that the fighter ace fully ‘arrived’.

AH-Aviation-Art

Immelmann, ‘the Eagle of Lille’, was famed not just as a fighter ace but as a technical innovator of the half-loop, half-roll combat tactic, ‘the Immelmann turn’. Born in 1890, he was an early enthusiast for flying. He was sent for pilot training in November 1914. He was a gifted student but, like von Richthofen, something of a loner, devoted to his mother and his dog and not imbued with the boisterous camaraderie of the mess. His early missions were entirely reconnaissance. In June 1915 he was shot down by a French Farman, only to emerge unscathed and with an Iron Cross (second class).

The arrival of the Eindecker at Douai aerodrome was the spark that ignited both his and Boelcke’s careers. On 1 August ten British planes shot up and bombed the airfield. Both German aviators leapt for their machines and mounted hot pursuit. Boelcke’s gun jammed, forcing him out of the fight. Immelmann did rather better. He took on two of the Brits and forced one down. Though wounded the Englishman landed safely and Immelmann courteously took him prisoner. This exploit earned him another Iron Cross, this time first class.

In the third week of September he brought down two more victims but was himself shot down a couple of days later when a French Farman peppered his fuel tank and shot away his wheels. He walked away from the wreck and, undeterred, chalked up kill no 4, another British plane, above Lille. He downed another over Arras and the sixth on 7 November. Just over a month later on 5 December he claimed a French Morane. By the standards of 1915, seven kills was a lot. The war in the air hadn’t reached the immense numbers of 1917–18. He and Boelcke became rivals that autumn, matching score for score.

One Royal Aircraft Factory BE2c was luckier. Captain O’Hara Wood was flying with Ira Jones as observer. The single Lewis gun operated by Jones had a series of mounts and for a full traverse had to be swapped between these. No easy matter especially when, as they’d dreaded, a lone Eindecker began stalking them over Lille. The hunter manoeuvred below and behind, the classic blind spot and came in gun blazing. Jones, unable to swap the Lewis fast enough, grabbed it and tried to fire holding the cumbersome weapon with its fearsome recoil like a Tommy gun. Not a great idea. The gun, like a living thing, leapt free of his hands and disappeared overboard. They were defenceless but Immelmann had run out of ammunition and flew off. Wood and Jones lived to fight another day.

It was on 12 January 1916 that the two rival aces both downed their eighth opponent. Eight kills was enough to win a coveted Blue Max, the talisman of success. With other manufacturers hot on his heels, Fokker attempted to up-gun the EIII model by adding two more machine guns and beefing up engine performance. In April 1916, Immelmann tested the new plane but the interrupter gear just couldn’t handle three guns and he shot himself down. Even two proved tricky and led to another crash in May.

Nonetheless, by early June he’d scored 15 victories. On the 18th his considerable luck ran out. He got into a dogfight with some of the ‘pushers’ of 25 Squadron. In the melée Lieutenant G. R. McCubbin and Corporal J. H. Waller claimed they’d hit Immelmann’s Fokker, causing his fatal crash. German sources claimed it was anti-aircraft fire, ‘Archie’ as it was known, that brought him down. Fokker himself was prepared to accept this verdict as it neatly avoided any questions about the working of the interrupter gear. Immelmann’s brother Franz was convinced otherwise, claiming he’d examined the wreckage and found the propeller shot in half. Whatever actually occurred, the first true fighter ace passed into legend.

AH-Aviation-Art

Oswald Boelcke was far more gregarious. Born a year later in 1891; he was an outstanding young sportsman and enthusiastic advocate of aggressive German militarism. At 13, he wrote a personal letter to the Kaiser asking for a place at a military academy. His turn came in 1914 – at Darmstadt he had his first taste of flying. He was still only an NCO for, in those very early days, the observers had most of the kudos, flyers were just the ones who drove. His older brother Wilhelm had also joined up and both won gallantry awards during that first year.

Boelcke was grounded by illness for a period but, early in 1915 he was assigned to Aviation Section 62 where he met his rival Immelmann. By the start of 1916, he was a star and, in January scored another four kills. These included a Vickers FB5, another two-seater pusher. Although these were rapidly approaching obsolescence as a design, they were very agile in the air and this crew gave Boelcke quite a fight. The two duelled for over half an hour, the pusher’s gymnastics enough to deny him a killing burst. The Englishman’s luck ran out almost directly above Boelcke’s own aerodrome at Douai.

He was not only a hit in Germany, he also won a decoration from the French. Nothing to do with flying this time, he had averted tragedy when a local lad slipped into the canal. Boelcke, a strong swimmer, dived in to rescue the boy from certain drowning. The French government awarded him a life-saving medal, though obviously not in person.

In February 1916, the great German offensive at Verdun opened up, the fearsome shrieking of the guns a doleful summons to months of hideous attrition. Boelcke’s jasta (fighter squadron) flew into this sector. Their prime role would be reconnaissance but on 13 March he clashed with a lone Voisin and set off in pursuit. The much slower French plane, pilot already rattled, made for the sanctuary of the clouds. The next Boelcke saw of it, the hapless observer was engaged in a desperate bid to stabilize the unwieldy brute of an aircraft by clambering out onto the wing.

This wasn’t recommended in any textbook or manual. Boelcke lacked the innate cruelty which spurred his successor von Richthofen and refrained from firing. It didn’t really matter as a sudden lurch sent the Frenchman off into the clouds and the long, very lonely fall to his death. Within a few days Boelcke had added another three Farmans to his growing tally.

The battles of 1916, across the ravaged landscapes of pounded fields and skeletal forests, grew larger and more intense, dwarfing anything that had gone before. So too in the skies. By September 1916, Boelcke was leading Jasta 2, equipped with the much-feared Albatros DII. He had his pilots fly in big formations, ‘circuses’ as the Allies dubbed them. Flying these formidable, fast fighters Boelcke pushed his score up to 40. In September alone, now battling over the Somme, he downed 11 British planes. He was Germany’s top ace yet he had none of the hubris that often went with that status. His belief was that victories belonged to the unit, more than the individual. It is perhaps ironic that one of his most promising novices was Manfred von Richthofen, the man who would come to exemplify the self-seeking glory of the individual hunter.

Boelcke was an inspirational and conscientious leader. He trained and mentored his pilots exhaustively and preached the gospel of successful air combat throughout the German air service. He issued his tactical doctrine for dog-fighting early in 1916 as the great battle for Verdun was beginning to unfold. This is the voice of experience:

(1) Always try to secure an advantageous position before attacking. Climb before and during approach in order to surprise the enemy from above, and dive on him swiftly from the rear when the moment to attack is at hand.

(2) Try to place yourself between the sun and the enemy. This puts the glare of the sun in the enemy’s eyes and makes it difficult to see you and impossible for him to shoot with any accuracy.

(3) Do not fire the machine guns until the enemy is within range and you have him squarely within your sights.

(4) Attack when the enemy least expects it or when he is preoccupied with other duties such as observation, photography or bombing.

(5) Never turn your back and try to run away from an enemy fighter. If you are surprised by an attack on your tail, turn and face the enemy with your guns.

(6) Keep your eyes on the enemy and do not let him deceive you with tricks. If your opponent appears damaged, follow him down until he crashes to be sure he is not faking.

It was on 28 October that Boelcke’s store of luck ran dry. All pilots, aces especially, lived with the knowledge that their life expectancy was finite. For beginners, it could be measured in weeks, sometimes days. With no parachutes the only hope was to nurse a stricken plane into a soft landing somewhere. Few slept well when they were set to fly the dawn patrol, that mystical time when light filters and brightens as the new day rises. Up at 04.30 with a brew of tea or cocoa and perhaps a shot to calm the nerves, then out and into the cockpit, the loneliest place on earth. This is five o’clock in the morning courage, no red mist or heat of battle, no comfort of comradely cloth at the touch. Each patrol may be your last, the way to flaming death. Pilots carried revolvers and pistols, not for cowboy antics but to spare themselves the agony of burning alive.

On that day, Boelcke had von Richthofen and Erwin Böhme as his wingmen, six Albatroses in the patrol. They dived to scrap with some DH2s and Böhme flew that bit too close, that second of inattention. His wing sliced clear through his chief’s upper wing struts, like a knife through cheese. The wing collapsed; all torsion and strength gone and Boelcke plummeted to his death. Ironically, he did manage to crash land the crippled Albatros but he had forgotten to fasten his seat harness and was killed on impact.

Erwin Böhme, born in 1879 and, like his boss, a serious sportsman, was devastated by the accident for which he blamed himself. Indeed, at one point, he became suicidal. Von Richthofen (nobody’s first choice for counselling perhaps) managed to talk him out of it and he went on to score 24 kills and win the Blue Max. He was killed in action on 29 November 1917.

Oswald Boelcke was buried in Cambrai Cathedral to a packed house, ablaze with gold braid. Even British prisoners of war from Osnabrück sent a card and the RFC dropped a wreath. There was still some romance left, for the moment anyway.