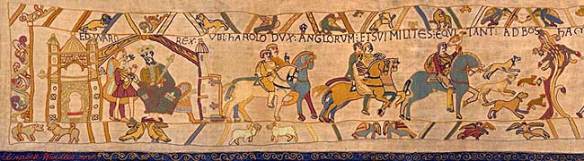

Bayeux Tapestry

This provides military historians with considerable and very useful data about the pre-events to the Battle of Hastings, the course of the conflict, and the weapons and the accoutrements employed by soldiers on both sides. It is the best contemporary illustration of protective armour. It is not actually a tapestry, but an embroidery, made by English ladies and maids in Kent. The tapestry, which was made on the order of Bishop Odo, measures 231.5 feet long (70.34 metres) and 19.5 inches wide (50 centimetres). It is stitched in eight colours on coarse linen. It was hung for a long time in Bayeux Cathedral. In his paper ‘Arms Status and Warfare in the Late Anglo-Saxon England’ N P Brooks makes two particularly interesting references to this:

‘We find that the English soldiers are shown through the battle as well-armed warriors with which we have seen to characterise the nobility — the thegns. They wear conical helmets and trousered byrnies; their shields are predominantly kite shaped, but occasionally round or sub-rectangular; they have spears and swords and sometimes two-handed battle axes.’

‘But it is at least clear that the tapestry artist distinguishes between the main body of the English army, which formed the shield wall and comprised soldiers with a full complement of the weapons and body armour, and the shield man who played a subsidiary role. The artist makes the same distinction between the noble and non-noble soldiers in depicting the Norman army with its uniformly well-armed knights and its archers who with single exception have no body armour at all.’

Armour

Norman and French horsemen wore a knee-length, one-piece mail shirt, with three-quarter-length sleeves, over a padded hauberk, which also protected the neck and throat. The bottom mail section was like an open skirt, as a mounted trooper did not need to protect his inner leg because it was not exposed when he was in the saddle. ‘Furthermore, the discomfort of riding in mail trousers might be palliated by padding, but damage to saddle and horse from friction could not.’ They protected their heads with an iron helmet fitted with a nasal guard. The English housecarls used almost identical armour. They also wore a protective garment of interlinking ring mail and a conical iron helmet with nasal guard. The main difference was that when the English fought on foot they needed to protect their groin area and thus laced up their lower mail coat to make trousers. By the 11th century mail was made with either round or flat rings riveted together to make a suit. Perhaps the strongest defence was achieved by a mail incorporating a mix of both flat and rounded rings. The weight of a mail coat stretching to the waist was about 28 to 42 pounds; a full-length coat weighed considerably more. Below the mail they wore a leather coat or padded jacket, which provided an essential additional safeguard. These protected a man from the contusion effects of a swinging sword or a mace blow, and much reduced the effects of a spear thrust or javelin strike. However, mail would not halt arrows. ‘A mail coat would be most effective if worn over a leather jerkin, though evidence for such an undergarment is absent until the Middle Ages.’ Certainly the Vikings adopted this custom from an earlier period.

The armour used by the English and Norman French military elite was therefore very similar. Generally it would have provided some protection against edged weapons, particularly those wielded in a slashing manner, but it would have been less effective against sword- or spear-points. It would not halt an arrow unless it was a long-range one. The mail coat, unless worn over a quilted jacket, would be vulnerable to a firm thrust from a very long spearhead of the type used by the English, which was designed to penetrate armour. Doubtless these inflicted casualties at Hastings. However, the large and very robust kite-shaped shields would safely halt short-range arrows, sword cuts and spear thrusts. This is clearly confirmed by the Bayeux Tapestry, which shows housecarl shields sustaining numerous hostile arrows. These shields, often made from lime-wood and covered with leather, had a maximum width of about 15.5 inches. They provided very good personal protection.

With one exception, depicted in panel 60 of the Bayeux Tapestry, no Norman French archers are shown wearing armour. Their apparent lack of this resulted in high casualties at Hastings. Their infantry, who are little depicted in the tapestry, carried swords and spears, wore mail and perhaps helmets, but despite this protection also suffered at Hastings. William of Poitiers stated: ‘The attackers (the Norman French) suffered severely because of “the easy passage” of the defenders’ weapons through their shields and armour.’ This indicates their poor and ineffective quality. The English militia also generally had no armour except a buff coat, although its extent depended on the wealth of an individual. They did possess the useful round shield, with its projecting iron boss to protect the left hand. Because this only screened a small area of the body it would have been necessary to move it promptly to block a sudden blow from an unexpected direction. The unarmoured English militia were susceptible to short and high-angled arrow fire and to mounted troopers if isolated in the open. However, when fighting in the shield-wall formation they were more secure and, with their spears of various lengths creating an intimidating frontal mass of gleaming blades, presented a formidable defence to any attacker. Furthermore, men of the militia were often adept at agile ducking-and-weaving techniques, and would sometimes, at close quarters, avoid a hostile blow then at once deliver a successful one with spear or long chopping scramasax.

The Norman French brought a corps of some two to three thousand professional archers to England carrying short bows with a range of about 150 yards. This weapon had little resemblance, in form or use, to the later-famous longbow used so successfully by Welsh and English archers. The English army had only a few bowmen, in the normal Anglo-Saxon military tradition, because the weapon was not highly regarded. A possible explanation for this may come from David Howarth, who wrote:

‘Bows in England were aristocratic sporting weapons, used for shooting deer, not human enemies, and archery was a strictly guarded mystique. For a long time past, the nobles had been fanatically jealous of their hunting rights, and if a poor man owned a bow he labelled himself a poacher. No common soldier in the fyrd would be any good at archery, or admit it if he was.’

It is thus ironic that at both the Stamford Bridge and Hastings battles the bow played a crucial part: King Harald Hardrada of Norway was fatally struck in the throat by an arrow, probably fired by a Yorkshire huntsman; King Harold II of England was later, possibly, wounded at the battle’s crisis point by another at Hastings.

Cavalry

The Norman French cavalry comprised troopers, who rode fairly sturdy but unprotected horses called ‘Destriers’. These were bred and drilled to carry an armoured horseman. Such troopers were called ‘Miles’ or ‘Chevaliers’. In England, military aristocrats (thegns) riding horses were referred to as ‘knights’. Clearly, mounted troopers of the 11th century, with their light lances or throwing spears bore very little resemblance to the true armoured knights of the 13th and 14th centuries, being neither equipped nor trained to achieve shock power. Eventually cavalrymen of the 14th century often wore intricately fashioned suits of plate armour, and closed helmets that afforded considerable protection. Their armoured steeds, such as the percheron or Clydesdale, were large and powerful, capable of carrying the weight of armour while reaching sufficient speed to make effective charges. These extremely expensive animals were also carefully bred and trained. The true knights used a strong couched lance and were trained to charge together, knee-to-knee in an irresistible and unwavering formation. ‘The horse-soldier of the eleventh century had not reached that advanced stage of military development.’ The Norman French cavalry were thus necessarily more circumspect and cautious owing to their inadequate armour and unprotected steeds. Doubtless, Norman French horsemen were periodically effective in battle against other cavalry because they were trained to fight them on a one-to-one basis. They might also deal effectively with isolated small groups of unprotected peasants equipped with shields and spears. However, against well-trained, experienced and professional infantry on the defensive and forming a firm shield wall, they were certainly not.

The Bayeux Tapestry depicts troopers advancing on the English in somewhat scattered groups called ‘contoi’ carrying differing weapons such as maces, swords, light spears or javelins. To be more effective they should have all, perhaps, carried spears and advanced in larger, more compact groups.

On approaching the enemy, the drill was to launch light lances from some distance in the hope of inflicting casualties before turning away, allowing comrades to repeat the manoeuvre. Their purpose was to create a break in the defence line into which they would advance, and attempt to widen it with slashing swords. However, until the shield wall eventually disintegrated, most horses approaching the English line too closely might have been decapitated and their rider killed with an axe or spear. Troopers may have attempted a forward spear thrust but most horses would naturally have shied away from the bristling and dense line of spears. It is not surprising that many Norman French warhorses could not withstand the heavy and continuous fusillades of missiles that greeted attacks some 20 to 30 yards from the English shield wall. So the Norman French cavalry did not at all resemble the later, fully developed feudal heavy cavalry. However, we should remember that the steep and boggy ground at Hastings was disadvantageous to horsemen.

It is interesting that the English cavalry used their horses in a very different manner from that practised on the Continent. The principle in England was that warriors rode to battle, fought dismounted, and then rode home after the conflict. From the time of King Alfred, the primary purpose of Anglo-Saxon cavalry (mounted infantry) was to move a small, mounted infantry army to an area of conflict at sufficiently high speed to confuse and surprise their adversary. They then fought on foot. Harold achieved this on his Welsh campaigns. The tradition of mounted Anglo-Saxon armies moving at great speed to confront an adversary continued throughout their history and the tactic was usually very successful. However, the procedure had one snag: the dismounted fyrd troops would naturally be unable to keep up with the mounted ones, which consequently reduced the size of the force that eventually fought the battle.

Battle of Brunanburh (AD 927), where King AEthelstan of England defeated a huge hostile confederation army led by Constantine, King of Scotland.

Another important role of the Anglo-Saxon cavalry was to provide a small, mounted mobile reserve to be employed only when an adversary started to display weakness in a battle that was being fought on foot. These troops then used their horses to convert a retreat into a rout. A classic example of this was at the Battle of Brunanburh, in 937, when King AEthelstan defeated the huge northern confederation host. According to the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, the English promptly followed up their victory (fought on foot) with a long pursuit by mounted infantry:

‘All through the day the West Saxons in troops

Pressed on in pursuit of the hostile peoples,

Fiercely, with swords sharpened on grindstone,

They cut down the fugitives as they fled’

Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, AD 937; p.108

It is often assumed that, because the English fought on foot at Hastings, they therefore always fought on foot, and employed horses only to reach, and then later depart from, a battlefield. At Hastings, of course, Harold wisely dismounted his housecarls in order to create a very strong defensive line. ‘Much as he would have liked, no doubt, to have kept his mounted housecarls in reserve, poised to launch a counter attack, the rather poor quality of his rustic army demanded that he dismounted his professional soldiers to stiffen the ranks of the militia.’

Swords used by the housecarls and Norman French troopers.

Those employed by both sides were similar. They were often of the double-edged type with fullered blades similar to those of Wheeler’s Type VII. English ones possibly retained more Viking features than those of their opponents. Some swords had imported inscribed Rhineland or high-quality English blades and were fitted with short, straight guards and beehive or Brazil nut pommels. Some patterns may have incorporated thick, faceted ‘wheel’ pommels, sometimes with bevelled edges, or the three-lobed, cocked-hat type. Some swords would have had a much longer guard, in a variety of simple but slightly differing forms, similar to those of Oakeshott’s Type IX. These were designed to provide better hand protection from opponents’ sword cuts. This type was to be a characteristic of the subsequent knightly swords. Swords of the late 11th and early 12th centuries tended to have rather larger pommels designed to act as counterweights to the rather longer, more tapering blades.