The Cayuga was the first ship through the water barrier at about 3:30 a. m. The Confederates did not discover the Cayuga until about 10 minutes later, when it was well under Fort Jackson. Understandably, General Duncan at Fort Jackson subsequently complained that Mitchell had failed to send any fire rafts to light the river at night, nor had he stationed any vessel below the forts to warn of the Union approach. The different naval commands and lack of cooperation between land and naval commanders indeed proved costly for the defenders.

As soon as they spotted the Cayuga, gunners at both Confederate forts opened up almost simultaneously, with the Union ships in position to do so immediately replying. Soon the river surface was filled with clouds of thick smoke from the discharges of the guns. This smoke obscured vision from both the ships and the shore, but on balance it favored the ships. Porter, meanwhile, had brought forward the five steamers assigned to his mortar schooners and these opened up an enfilading fire at some 200 yards from Fort Jackson, pouring into it grape, canister, and shrapnel shell, while the mortars added their shells. This fire did drive many of the Confederate gun crews from their guns and reduced the effectiveness of those who remained.

The Pensacola, the second Union ship through the obstacles, was slow to get under way, and this meant that for some time the Cayuga faced the full fury of the Confederate fire alone. Lieutenant George H. Perkins, piloting the Cayuga, had the presence of mind to note that the Confederate guns had been laid so as to concentrate fire on the middle of the river and therefore took his ship closer to the walls of Fort St. Philip. Although its masts and rigging were shot up, the hull largely escaped damage.

The captain of the Pensacola, Captain Henry W. Morris, apparently interpreted Farragut’s orders to mean that he was to engage the forts. Halting his ship in the middle of the obstructions, he let loose a broadside against Fort St. Philip, driving the gun crews onshore to safety. On clearing the obstructions, he ordered a second broadside against the fort. But stopping the Pensacola dead in the water made it an ideal target. It took nine shots in the hull, and its rigging and masts were also much cut up. The Pensacola also suffered 4 killed and 33 wounded, more than any other Union ship in the operation that day.

The leading division continued upriver, engaging targets as they presented themselves. The remaining Union ships followed, firing grape and canister as well as round shot. The shore batteries had difficulty finding the range, and damage and casualties aboard these vessels were slight.

About 4:00 a. m., the Confederate Navy warships above the forts joined the battle. The most powerful of these, the McRae, lay anchored along the shore 300 yards above Fort St. Philip when its lookouts spotted the Cayuga. Lieutenant Thomas B. Huger, captain of the McRae, ordered cables slipped and fire opened. The McRae opened up with its port battery and pivot gun, but the latter burst on its 10th round. The Cayuga continued upriver, passing the McRae. Two other Union ships, the Varuna and Oneida, then exited the smoke and steamed past the McRae without firing on it, probably taking it for a Union gunboat. Huger ordered his vessel to sheer first to port and then to starboard, delivering two broadsides. The Varuna and Oneida also sheered and returned fire. Each of these ships mounted two XI-inch Dahlgrens in pivot and these guns soon told. The explosion of one Union shell started a fire in the McRae, and only desperate efforts by the crew kept the blaze from reaching the magazine.

Although most of the remaining lightly armed Confederate warships fled upriver on the approach of the Union ships, this was not the case with the ram Manassas. Although his ship was armed with only a single 32-pounder, Lieutenant Alexan der Warley was determined to attack, even alone. Warley understood that the only chance for a Confederate victory lay in an immediate combined assault by the gunboats and fire rafts to immobilize the Union vessels long enough for the heavy guns in the forts to destroy them.

The Manassas lay moored to the east bank of the river above Fort St. Philip, when flashes in the vicinity of the obstacles indicated action in progress. Warley immediately ordered his ship to get under way. He attempted to ram the Pensacola, but skillful maneuvering by the Union pilot avoided a collision, and the Pensacola let loose with a broadside from its IX-inch Dahlgren guns as the Manassas passed. Damaged in the exchange, the Confederate ram nonetheless continued on.

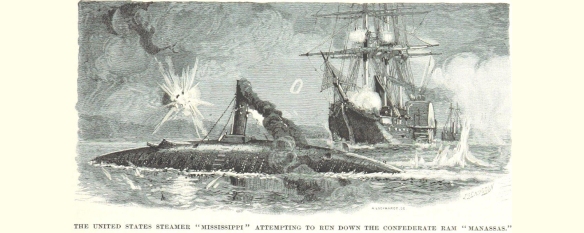

Warley then spotted the side-wheeler Mississippi. Lieutenant George Dewey tried to turn his ship so as to ram the onrushing Manassas, but the latter proved more agile than the Union paddle wheeler and was able to strike the Mississippi a glancing blow on its port side, opening a large hole there but failing to fatally damage the Mississippi.

As the Union ships cleared the forts, they came under fire from the Confederate ironclad Louisiana along the riverbank. Its gun ports were small and did not allow a wide arc of fire, so the gun crews scored few hits.

Proceeding north, the leading Cayuga overtook some of the fleeing Confederate vessels and fired into them. Three of the Confederate gunboats struck their colors and ran ashore. The Varuna and Oneida soon came up, but in the confusion sailors in the Varuna mistook the Cayuga for a Confederate vessel and fired a broadside into it.

Impatient with the Pensacola’s slow progress, meanwhile, Farragut ordered the Hartford to pass it and then climbed into the mizzen rigging so as to secure a better view over the smoke. As the Hartford proceeded upriver, Farragut saw a fire raft blazing off the port bow, pushed forward by the unarmed Confederate tug Moser. Farragut ordered his own ship to turn to starboard, but it was too close to the shore and its bow immediately grounded hard in a mud bank, allowing Captain Horace Sherman of the Moser to position the raft against the Hartford’s port side. The blaze soon ignited the paint on the side of the Union vessel, which then caught the rigging. With his ship on fire and immobilized, Farragut thought it was doomed. Fortunately, the gunners at Fort St. Philip were unable to fire into the now stationary target as the fleet’s fire had dismounted one of the fort’s largest guns and another could not be brought to bear.

Farragut came down out of the rigging to the deck where he exhorted the Hart ford’s crew to fight the fire. Gunfire from the flagship, meanwhile, sank the Moser. Farragut’s clerk, Bradley Osbon, brought up three shells, unscrewed their fuses, and dropped them over the gunwale of the Hartford into the fire raft. The resulting explosions tore holes in the raft and sank it, extinguishing the flames. With the raft gone, the Hartford’s crew was able to extinguish the fires. The men cheered as their ship backed free of the mud bank and resumed course upriver.

In the confusion and smoke, accidents occurred. The gunboat Kineo collided with the sloop Brooklyn; although seriously damaged, the Kineo was able to continue on past the forts. The Brooklyn, meanwhile, plowed into one of the Confederate hulks, then suddenly ground to a halt just north of the obstructions, its anchor caught in the hulk and hawser taut. The river current then turned the sloop broadside to Fort St. Philip. With the gunners ashore having found the range and the Brooklyn taking hits, a crewman managed to cut the cable and free the sloop.

Captain Thomas T. Craven of the Brooklyn ordered it to pass close to Fort St. Philip, the sloop firing three broadsides into the Confederate works as it steamed past. The Brooklyn then passed the Louisiana at very close quarters. In the exchange of fire, a Confederate shell struck the Union ship just above the waterline but failed to explode. Later, the Brooklyn’s crew discovered that the Confederate gunners had failed to remove the lead patch from the fuse.

Smoke from the firing was now so thick that it was virtually impossible to see and take bearings. Craven merely conned his ship in the direction of the noise and flashes of light ahead. But the tide carried the sloop over on the lee shore, perfectly positioned for the guns of Fort Jackson. As the sloop touched bottom, Craven saw the Manassas emerge from the smoke.

Warley had previously tried to ram the Hartford without success. The Manassas had taken a number of Union shell hits and its smokestack was riddled and speed sharply reduced. Warley decided to take the ram down river to attack Porter’s now unprotected mortar boats. But when the Confederate forts mistakenly opened up with their heavy guns on the Manassas, Warley decided to return upriver. At that point he spotted the Brooklyn lying athwart the river and headed for Fort Jackson. Warley ordered resin thrown into his ship’s furnaces to produce maximum speed and maneuvered the ram so as to pin the Brooklyn against the riverbank.

Seamen aboard the Brooklyn spotted the ram’s approach and gave the alarm. Craven ordered the sloop’s helm turned, but this could only lessen, not avoid, the impact. Only moments before the collision, a shot from the Manassas crashed into the Brooklyn but was stopped by sandbags piled around the steam drum.

The Manassas struck the Union ship at a slight angle, crushing several planks and driving in the chain that had been protecting the ship’s side. Craven was certain his ship would go down, but the chain and a full coal bunker helped lessen the impact. Meanwhile, the Manassas disengaged and resumed its progress upriver.

The tail of Farragut’s force, Porter’s mortar flotilla, was also under way. When his vessels came under fire as they approached Fort Jackson, Porter ordered the mortar boats to stop and open fire. This was about 4:20 a.m. The mortars fired for about a half hour, sufficient time it was thought for the remainder of the Union squadron to have cleared the forts. However, when Porter signaled a halt, some of the Union ships were still engaging the forts.

In the thick smoke the Wissahickon, the last ship in the first division, grounded. As the sun rose, Lieutenant Albert N. Smith, the Wissahickon’s captain, discovered he was near three third-division ships, the Iroquois, Sciota, and Pinola, but also in the vicinity of the Confederate gunboat McRae, soon hotly engaged with the much more powerful Iroquois. The McRae was badly damaged in the exchange and Lieutenant Huger was mortally wounded; 3 men were killed outright and another 17 were wounded.

At this point the Manassas came on the scene. Warley tried without success to ram first the Iroquois and then the other Union ships. Realizing the danger if their ships were to be disabled close to the Confederate forts, the Union captains then broke off firing on the McRae and resumed their passage upriver.

Three of Farragut’s ships failed to make it past the forts. The Kennebec and Itasca ran afoul of the river obstructions. In an effort to back clear, the Itasca then collided with the Winona. The Itasca then took a 42-pounder shot through its boiler and had to abandon the effort. The Winona was able to retire before dawn. The Kennebec, caught between the two Confederate forts at daybreak, also withdrew. Fourteen of the 17 ships in Farragut’s squadron had made it past the forts, however.

Farragut lost one ship, the screw steamer Varuna, in the first division. At about 4:00 a. m., Lieutenant Beverly Kennon of the Louisiana state gunboat Governor Moore spotted the Varuna, which was faster than its sister ships and was advancing alone. Kennon immediately ordered the Governor Moore to attack; but in order to reach the Varuna, it was obliged to run a hail of shot and shell from the other Union ships, which cut it up badly and killed and wounded a number of its crew. But the exchange of fire also produced so much smoke that the Confederate gunboat was able to escape and follow the Varuna upriver.

Some 600 yards ahead of the trailing Union ships, the Governor Moore trailed the Varuna by 100 yards. The Union warship engaged its adversary with its stern chaser gun and repeatedly tried to sheer, so as to get off a broadside, but Kennon carefully mirrored the motions of his adversary and was thus able to avoid this. Nonetheless, the Governor Moore took considerable punishment. Shot from the Varuna’s stern chaser killed or wounded most of the crewmen on the Confederate vessel’s forecastle. With his own ship then only 40 yards from his adversary and his bow 32-pounder unable to bear because of the close range, Kennon ordered the gun’s muzzle depressed to fire a shell at the Union warship through his own ship’s deck. This round had a devastating effect, raking the Varuna.

Kennon ordered a second shell fired, with similar result. With the two ships only about 10 feet apart and after firing a round from its after pivot gun, the Varuna sheered to starboard so as to loose a broadside, but Kennon could see the Union ship’s mastheads above the smoke and guessed what was intended. Swinging his own ship hard to port, he smashed it into the Union vessel. The Governor Moore then backed off and rammed the Varuna again, taking a full broadside from the Union ship in the process that made casualties of most of the Confederates on the weather deck. Shortly thereafter, however, another Confederate warship, the Stonewall Jackson, appeared and rammed the Varuna on its opposite, port, side. This blow produced such damage that the Varuna’s pumps were unable to keep it afloat, and Commander Charles S. Boggs ran his ship ashore. Having absorbed two broadsides from the mortally wounded Union vessel, the Stonewall Jackson was itself in a sinking state, and its captain ordered it also run ashore and burned to prevent capture.

As he watched the Varuna ground, Kennon was faced with a new problem in the remaining rapidly closing Union ships, which soon subjected the Confederate gunboat to a devastating fire. His own ship in danger of going down in the river, Kennon grounded it just above the stricken Varuna and ordered it fired. The casualty toll on the Governor Moore was appalling. Fifty-seven men had been killed in action and 7 more wounded out of a crew of 93.

As dawn broke, between 5:30 and 6:00 a. m., the Union ships assembled at Quarantine Station. At this point the Manassas suddenly appeared, heading for the squadron. Standing on the hurricane deck of the Mississippi, Lieutenant Dewey saw the Hartford, blackened from the recent fire, steaming by. Farragut was in its rigging and calling out “Run down the ram!” But when Warley saw the extent of his opposition, he knew the battle was over. The speed of the Manassas was now so much reduced, and it had sustained such damage that an attack would have been suicidal. Warley headed his ship ashore and ordered his crew to scatter.

The battle for the lower Mississippi was over. With the Union fleet past the forts and the Confederate gunboats destroyed, there was now no barrier between Farragut’s squadron and New Orleans. Union casualties had been surprisingly light: the total from April 18 to April 26 was just 39 killed and 171 wounded. Farragut reported to Porter: “We had a rough time of it . . . but thank God the number of killed and wounded was very small considering.”