While Early deployed his men slowly and cautiously, the morning hours passed. Shortly after noon some echoes of action may have reached Lee from the north-east, but the pine forests were thick, and sound did not carry far. Ere long, however, he must have been informed that while Johnson’s division was advancing toward Bartlett’s Mill, the ambulance train had been fired on from the north. Steuart’s brigade had moved out from the road, the rest of the division had been recalled, and a line of battle had been formed facing the Rapidan. Meantime, Early had completed his dispositions and had put Rodes and Hays in line, opposite what appeared to be a strong force at Locust Grove. Instead, therefore, of having a race for Chancellorsville, with an enemy moving southeastward from the fords of the Rapidan, Lee found the Federals in his front and on his left flank. Still, this situation did not altogether contradict the view that the enemy was advancing toward Fredericksburg or the Richmond and Fredericksburg Railroad. The Federal columns might have been delayed in crossing the fords opposite Lee’s front, or the forces that had been encountered by Early might be a heavy rearguard.

About 1 P.M., Heth’s division, at the head of Hill’s corps, reached Verdiersville. Lee gave the men an hour’s rest and then directed that they continue their march up the plank road toward Mine Run. Some time after the last regiment of the division had filed past, Lee himself rode forward with his staff. When he had gone about two miles he found the division halted and heard firing ahead. At length, Heth rode up and reported that when his advance had reached a point between two and three miles from Verdiersville, he had come upon a detachment of Stuart’s cavalry skirmishing with Federals along the plank road. Heth had thrown forward skirmishers to support the cavalry, but they had been driven in quickly. Several attempts to drive off the enemy had been made to no purpose. Might he advance his whole division and feel out the strength of the Federals? Lee consented, and Heth hurried away.

In rear of Heth’s line of battle, Lee waited. North of him, where Johnson’s division had been fired upon, a hot action was in progress. To the north-east, Rodes’s and Early’s men were skirmishing briskly. And now Heth was about to engage. It was, to say the least, stiff and extended resistance to be offered by an adversary who was supposed to be hastening toward the railroad below Fredericksburg.

General Hill, who joined Lee about this time, had been of opinion that the enemy had only cavalry in his front, but General Stuart, in a note sent at 2 o‘clock, expressed the belief that the enemy was advancing up the Rapidan. Most significant of all was a dispatch from General Thomas L. Rosser, one of Stuart’s new brigadiers. He reported that during the morning he had found the ordnance train of the I and V Army Corps on the plank road near Wilderness Tavern. Attacking, he had captured 280 mules and 150 prisoners, and—what was of far greater immediate importance—he had observed that the wagons were headed for Orange Courthouse, not for Chancellorsville.

Was Meade, then, moving against the Army of Northern Virginia, rather than to the Richmond and Fredericksburg Railroad? It seemed probable, but until the purpose of the enemy was more fully disclosed, Lee hardly dared hope that his numerically inferior army would have the opportunity of fighting a defensive battle. When, therefore, Heth returned late in the evening and announced that he had driven the enemy’s skirmishers from their advanced position, Lee was unwilling to authorize an advance until he had personally examined the enemy’s position and had seen for himself how strongly the Federals were posted. He ordered Anderson’s division of Hill’s corps to the right and rear of Heth to fill in the gap between Heth’s left and Early’s right, and after Hill returned from making these dispositions, Lee went with him on a reconnaissance.

By this time he had information that the force which Johnson’s division had encountered on its advance was an entire corps, part of which had been driven off, with a Confederate loss of some 545 men. Such additional intelligence as reached Lee confirmed the suspicion formed after the receipt of Rosser’s dispatch and led him to conclude that the whole of the Army of the Potomac was in his front. It was not necessary to go in search of the enemy; the enemy was searching for him! For the first time since Fredericksburg the army was to have a chance of receiving the enemy’s assaults instead of attacking. As it was now nearly dark, Lee determined not to advance against the strong position of the Federals that evening, but to withdraw to the west bank of Mine Run during the night and to await developments. Early retired behind the run without additional orders and took up a good line there. Hill’s corps was recalled during the night.

When Early reported, about daylight on the 28th, Lee instructed him to move his troops still farther westward to an even better defensive position, for if Meade was of a mind to assume the offensive, Lee wished to meet it on the most favorable ground. But before Early could execute this order he found the Federal infantry advancing to Mine Run and, with Lee’s permission, he waited to repulse them. A heavy rain began to fall while the army stood ready to resist attack, and this downpour seemed to deter the enemy. Making one or two minor adjustments in his front, to protect it from enfilading fire, Lee ordered earthworks thrown up. As the earth began to fly, he rode or walked among the soldiers with encouraging words. “In an incredibly short time (for our men work now like beavers),” one officer wrote shortly afterwards, “we were strongly fortified and ready and anxious for an attack.”

But the enemy did not attack that day, nor the next, though he opened a heavy artillery fire on the 29th and threatened to assault. Lee could not believe that Meade had made elaborate preparations and had moved his whole army for a mere demonstration, so he continued to strengthen his earthworks, while the enemy set to work to emulate him. The day witnessed the strange spectacle of two great armies exchanging occasional cannon shots and contenting themselves, for the rest, with seeing which of them could pile the higher parapets. It chanced to be a Sunday, and the weather was very cold. The men who were not on duty gathered about their fires and, here and there, assembled in prayer meetings incident to the great revival that showed no sign of losing its force. As Lee rode out on a tour of inspection, he, with his staff, chanced to pass one of these gatherings. He promptly dismounted and participated reverently in the service.

On the 30th, the weather still very cold, Stuart reported early that the enemy was forming line of battle on the south side of the Catharpin road. But once again expectations were deceived, and no general engagement occurred. Puzzled as Lee was by Meade’s lack of action, he was so confident of the outcome of a Federal attack that he notified Davis not to reinforce him with troops that might be needed for the defense of Richmond. He continued to keep a sharp lookout on his flanks, however, especially on his right, where there had been some active cavalry skirmishing on the 29th.

Sometime on the 30th a hurried message arrived from General Stuart, asking Lee to come to him at once. Lee went with the messenger, and found Stuart in the company of Wade Hampton in rear of the left flank of the enemy. Hampton had reached that position unobserved and believed that it was possible to turn the Federal position and repeat Jackson’s movement at Chancellorsville. Lee studied the ground carefully and conferred with some of his officers but decided against immediate action, probably because he could not bring the troops into position in time to attack that day, or else because he wished to wait a little longer in the hope that Meade would attack.

When the morning of December 1 came and went with no further sign of any intention on the part of the Federals to press the offensive, Lee lost hope that the Federals would assume a vigorous offensive and he determined to take the initiative himself. “They must be attacked; they must be attacked,” he said. Hill was directed to draw Anderson’s and Wilcox’s divisions of veterans to the extreme right, probably with an eye to moving them to the position Hampton had discovered the previous day, and Early was instructed to extend his right to cover the ground vacated by the two divisions. Lee’s plan was to carry Wilcox and Anderson beyond the enemy’s left flank and to sweep down it, while Early held the defenses on Mine Run with his own corps and with Heth’s division. The weather was so cold that water froze in the canteens of the men that night, but the movement got under way smoothly and without interruption by the enemy, though there were some evidences of activity within the Federal lines.

Before daybreak on December 2 the whole army was ready; Anderson and Wilcox were in position; the rest of the men were on the alert; the gunners were at their posts. As soon as it was light enough to see, the skirmishers looked eagerly through the woods for the Federal pickets. But they scanned the thickets in vain: The enemy was gone! The withdrawal was so unexpected that a staff officer who was sent to order Hampton’s division to pursue the foe found the videttes on the watch for an advance by the Federal divisions that were then fast making their way toward the fords of the Rapidan. Informed of the changed situation, the cavalry rode fast and hard, and the infantry followed through woods the retiring enemy had set afire. Meade, however, had a long lead, for he had started during the late afternoon of the 1st, and the chase was fruitless.

“I am too old to command this army,” Lee said grimly, when he saw that his adversary had retreated, “we should never have permitted those people to get away.” In deep depression of spirits, and indignant at the many evidences of purposeless vandalism, he soon recalled the infantry and moved back toward his camps higher up the stream. When he had cooled down, two days later, he wrote of Meade, “I am greatly disappointed at his getting off with so little damage, but we do not know what is best for us. I believe a kind God has ordered all things for our good.”

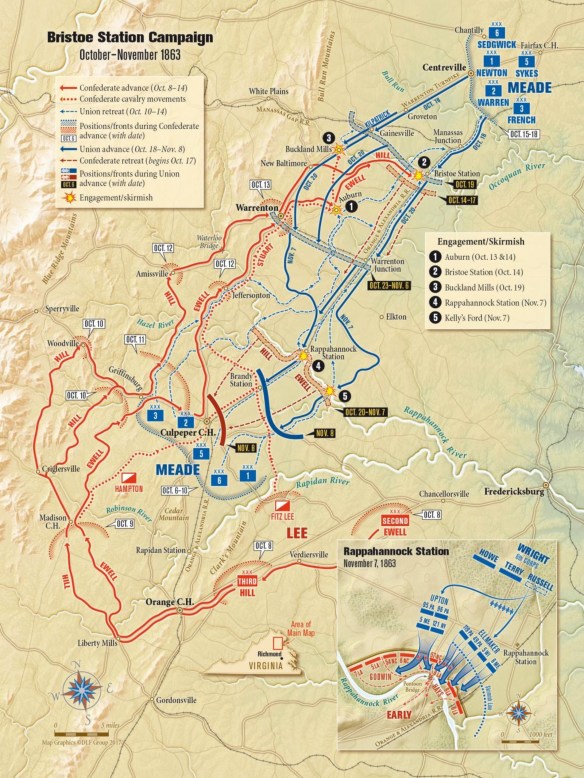

Except for a troublesome raid by General W. W. Averell against the Virginia and Tennessee Railroad, beginning December 11, the Mine Run episode marked the end of active operations in 1863. It had been for Lee no such year of victory as ‘62. The bloody glory of Chancellorsville had been dimmed by the defeat at Gettysburg. The limit of the manpower of the South had almost been reached. The spectre of want hung over the camps. From the time of the return to the line of the Rappahannock and Rapidan after the Pennsylvania campaign, the army had met with no major disaster, but it had scored no success. Taking Bristoe Station, the capture of the Rappahannock bridgehead and the movement to Mine Run as one campaign, Lee’s losses had been 4255 and his gain had been nil.

These casualties, amounting to nearly a whole division, were not due to recklessness on the part of the men, or to ready surrender. Aside from those killed and wounded in Johnson’s division as it marched to Mine Run, virtually the whole of Lee’s losses were attributable to defective leading or to carelessness on the part of commanding officers. The operations had lacked not only the dash of Jackson but the tactical skill of Longstreet, as well, and they must have raised serious misgivings in Lee’s mind as to the future handling of the two corps left him. The impetuosity that had marked A. P. Hill ever since the battle of Mechanicsville cost the army the service of two effective brigades at Bristoe Station, and along with them the possibility of a substantial victory. Not since McLaws’s slow bungling at Salem Church had there been a worse example of generalship. The defense at Rappahannock Bridge and at Kelly’s Ford on November 7 was unskillful, even though no blame could be fixed. As for Ewell, he made no mistake at Bristoe Station and was not present at Mine Run, but he was so enfeebled by his former wounds that Lee was deeply concerned for him. With his quaint language, his aquiline countenance, and his wooden leg, he was a picturesque and appealing figure as he rode gamely among the troops. Everyone was puzzled to know how he contrived to stick on his horse. Lee, however, had to ask himself the more serious question of how Ewell could sustain the hardships of an active campaign, and that question had added point, because, in Longstreet’s absence, Ewell was ranking lieutenant general. If Lee went down, the command would devolve, temporarily at least, on him. Taylor probably voiced the secret feeling of his chief when he wrote, “I only wish the general had good lieutenants; we miss Jackson and Longstreet terribly.” The full weight of the army rested on Lee. He had to give to his corps commanders a measure of direction that had been unnecessary when he had operated with two corps under “Stonewall” and “Old Pete.” His might now be the responsibility of fighting the battles as well as of shaping the strategy. It was a heavy burden to be borne by a man whose heart symptoms were becoming aggravated.

The final operations of 1863 marked two new stages in the methods of war employed by the Army of Northern Virginia. They increased, in the first place, the faith of the troops in the great utility of field fortification. Lee’s construction of the South Carolina and of the Richmond lines had early demonstrated his belief that the commanding general should provide the maximum cover for his men when they were to be engaged for a long period in defensive operations. His use of field works did not date, as some authorities have claimed, from Mine Run, but from Fredericksburg and, more particularly, from Chancellorsville. After Mine Run, as the declining strength of the army forced it more and more to the defensive, field fortification became a routine. Every soldier was a military engineer.

If the infantry were finally converted to the use of earthworks at Mine Run, the cavalry developed, in the second place, an important new tactical method during the last five months of the year. Prior to the Bristoe campaign, the sharpshooters of the cavalry had been organized officially, and during the second battle of Brandy, October 11, they were dismounted by regiments and were effectively employed. In that action, Lomax’s whole brigade left their horses in the rear and for a time occupied a line of breastworks. Again, in the “Buckland Races,” Fitz Lee used some of his cavalrymen on foot. During the Mine Run operations, when the cavalry had to contend with a thick forest and heavy undergrowth, through which it was impossible for mounted men to pass, these tactics of dismounted action were developed. In the fighting of November 27, and again on the 29th and on the 30th, the troopers were led against the enemy by regular infantry approaches. From that time onward, as the necessities of the service demanded, the dismounted cavalrymen were frequently summoned to support the thinning line of the infantry. It was hard on the troopers but it saved horses, and it prepared the army more fully for the fearful tests that awaited in the campaign of 1864.