Back on the south side of the Rappahannock, the Army of Northern Virginia, which had been in good spirits during the Bristoe expedition, was satisfied that the year’s bitter fighting had at last been ended. Meade was somewhat of the same mind. He believed that Lee had advanced to Bristoe Station in order to destroy the railroad and thereby to hold off the Army of the Potomac while he sent more troops to Tennessee—”a deep game,” Meade said, “and I am free to admit that in the playing of it [Lee] has got the advantage of me.” But Lee was not so sure that all was over for the winter. He presumed that Meade would advance again. “If I could only get some shoes and clothes for the men,” he said, “I would save him the trouble.” On the possibility that supplies might be forthcoming for a limited offensive, he kept his pontoons on the Rappahannock, close to the piers of the old railroad bridge at Rappahannock Station. Simultaneously, he fortified a bridgehead on the north bank of the river. In doing this, he had a defensive as well as an offensive object in view, for as long as he was able to maintain the pontoon bridge he would be in position to divide Meade’s forces and could throw a flanking column over the river in case his adversary attempted to cross the Rappahannock, either above or below him.

Two weeks and more passed without important incident. The Army of the Potomac advanced to Warrenton, halted there for some days, and then began to feel its way slowly toward the Rappahannock; but Meade did not appear to threaten a general advance. During the respite thus afforded him, Lee experienced some concern over the unsatisfactory handling of affairs in western Virginia. There was, too, the usual futile effort to get reinforcements, especially of cavalry; and some correspondence passed with the War Department over a proposed transfer of troops to South Carolina, a movement against which Lee protested with the reminder that “it is only by the concentration of our troops that we can hope to win any decided advantage.” For the rest, Lee was content to give the men a vacation from marching and to remain at headquarters near Brandy Station, as quietly as was possible, for he was in constant pain, and for five days at the beginning of November was unable to ride. He had set November 5 for a review of the cavalry corps and had invited Governor John Letcher to witness it, but he was afraid he would not be able to endure this ordeal. Fortunately, though, he felt better that day and was able to participate in a ceremony that delighted the spectators and made the heart of Stuart proud. Several of Lee’s nephews and his youngest son were among those passing in front of the commander, who had a secret parental delight in noting that Rooney’s old regiment, the Ninth Virginia, made the finest showing.

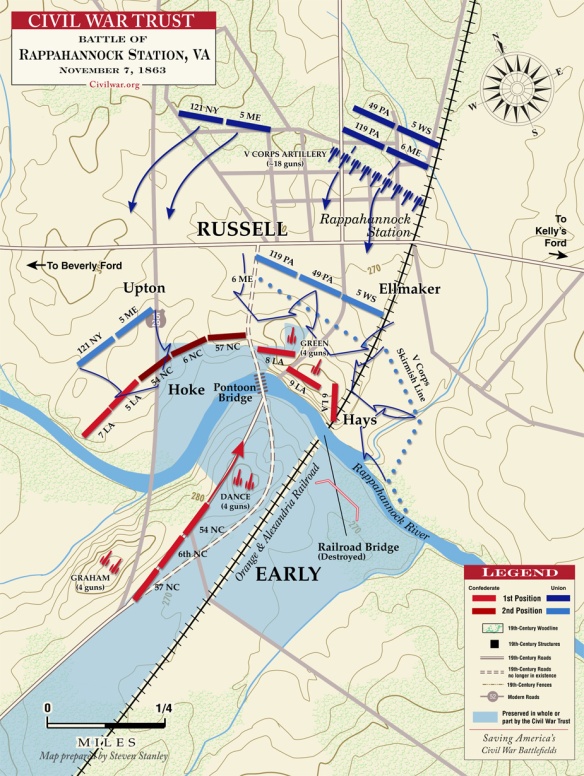

Ever since the famous review of June 8, 1863, on that same historic field near Brandy Station, there had been a tradition in the army that pageantry was always followed by action. Once again this was vindicated. On the very day of the ceremonies the outposts reported the enemy advancing to the Rappahannock, and by noon on November 7, Federal infantry was in front of the tête de pont, while a large column was moving to Kelly’s Ford. As the ground on the south bank of the river at this ford was somewhat similar to that at Fredericksburg, in that it offered no deep defensive position from which to dispute a crossing, Lee intended to permit Meade to cross and then to attack him in superior force by holding part of the Federal force at Rappahannock Bridge. The Confederate troops were well disposed for this purpose. Ewell’s corps extended from Kelly’s Ford to a point beyond the bridgehead, Hill was on the upper stretches of the river, guarding the fords, and the cavalry covered both flanks.

When, therefore, Lee learned during the afternoon that the enemy had crossed at Kelly’s Ford, in front of Rodes’s division, he felt no particular concern. Johnson’s division was ordered to reinforce Rodes, Anderson was brought up close to the left of the railroad to support Early, who commanded the crossing, and the rest of Hill’s corps was put on the alert. Early had only Hays’s brigade on the north side of the river, in the works covering the pontoon bridge, and no units resting directly on the south bank; but without waiting for orders he advanced the rest of his division as soon as he heard that the enemy was concentrating in front of the tête de pont. Lee overtook Early on his way to the bridge and rode forward with him to a hill overlooking the position on the north bank.

Early hurried across the pontoon bridge, which was in a protected position, and Lee busied himself with disposing two batteries of artillery that were at hand. After half an hour or more, Early returned and reported that the enemy was gradually approaching the bridgehead under cover of a range of hills, and that the defending force was entirely too small to man the works. On the arrival from the rear of the head of Hoke’s command, the leading brigade of Early’s division, Lee ordered it over the bridge to support the troops already in position, but he declined to send more men to the north side. He believed that seven regiments would suffice to defend the bridgehead, inasmuch as the enemy could not advance on a longer front than the two brigades held.

Soon after Hoke’s brigade crossed, the Federals planted artillery where it could deliver a cross-fire on the bridgehead. Answering this challenge, the Confederate batteries quickened their fire, and Lee moved up to a hill nearer the river in order that he might observe the fight more closely. He soon discovered that the Southern gunners were accomplishing nothing because of the length of the range, and he ordered the fire halted.

In a short time dusk fell. A heavy south wind was blowing and carried away from the river the sound of the action. Soon the Federal ordnance ceased its practice. Shortly afterward flashes of musketry could be seen, but these were not long visible. This stoppage of fire convinced Lee that the Federals were merely making a demonstration against the bridgehead, probably to cover their advance at Kelly’s Ford; and as the enemy had never made a night attack on a fortified position held by the infantry of the Army of Northern Virginia, Lee concluded that the action in that quarter was over for the day. If the enemy came too close, he believed it would be possible for the troops on the north side to return to the south bank under cover of the batteries. Leaving General Early in charge, Lee rode back to headquarters, where he received the unwelcome news that the enemy had captured parts of two regiments at Kelly’s Ford, had laid a pontoon bridge, and had sent a large force over to reinforce the first units.

In this situation, of course, the logical course was to carry out the plan previously prepared for this contingency-to hold the bridgehead, to demonstrate there, and to move the greater part of the army eastward to engage the troops that were facing Rodes and Johnson at Kelly’s Ford. But before Lee could execute this plan, Early sent him almost incredible news from the tete de pont: After darkness had fallen, the enemy had massed in great strength, had stormed the bridgehead and had captured the whole force on the north side, except for those who had swum the Rappahannock or had run the gauntlet over the pontoon bridge! Fearing an attempted crossing, Early had set fire to the south end of the bridge and had lost the pontoons.

Lee’s defensive plan collapsed as he read Early’s dispatch. If the bridgehead was gone, it would be futile to demonstrate on the left while attacking on the right at Kelly’s Ford. Meade would laugh at the helpless Southern troops opposite the old railroad bridge. Moreover, the Army of Northern Virginia could not safely remain where it was, on a shallow extended front, with the Rapidan River behind it. Pope had nearly been caught there, with the positions reversed. Lee saw that he must move back, and at once. Within a few hours after Early had reported the disaster at Rappahannock Bridge, the troops had been routed out from their huts, the wagons had been packed, and the army was retiring to a line that crossed the Orange and Alexandria Railroad two miles north-east of Culpeper and barred the road from Kelly’s Ford by way of Stevensburg. Lee was, of course, concerned over this hurried movement, but he did not let it upset his poise. As he prepared to leave his headquarters near Brandy Station, he went to Major Taylor’s tent and found that officer stretched out in front of a roaring fire. “Major Taylor is a happy fellow,” he commented cheerfully, and went on his way. There was no sleep for Lee that night, and he was glad to see his faithful staff officer snatching rest while he could.

As the army formed line of battle in its new position on the morning of November 9, there was some expectation that Meade would attack, but when he let the day pass without following up his success at Rappahannock Bridge, Lee again put the columns in motion and, on November 10, was back on the south side of the Rapidan, whence he had started one month and one day previously for Bristoe Station.

The troops were much chagrined at the necessity which threw them back from the Rappahannock. The affair of the bridge was, Taylor insisted, “the saddest chapter in the history of this army,” showing “miserable, miserable management.” Sandie Pendleton, son of the chief of artillery and one of Jackson’s former staff officers, was burning for Lee to attack Meade and “let us retrieve our lost reputation.” He went on: “It is absolutely sickening, and I feel personally disgraced by the issue of the late campaign, as does every one in the command. Oh, how each day is proving the inestimable value of General Jackson to us.” A young North Carolinian, less close to the saddles of the mighty, probably voiced the sentiments of the army when he said, “I don’t know much about it but it seems to me that our army was surprised.” Early was intensely humiliated, though he did not feel himself responsible. Lee called for prompt reports both of the attack at the bridgehead and of the capture of the skirmishers at Kelly’s Ford; but when the documents were received he could only say that sharpshooters had not been properly advanced in front of the bridgehead, and that Rodes had erred in placing two regiments on picket duty, instead of one, at Kelly’s Ford. “The courage and good conduct of the troops engaged,” he said, “have been too often tried to admit of question.”

The morale of the army was not impaired by this unhappy affair. The men went cheerfully to work building new huts, and contrived to make themselves comfortable after a fashion. Lee sought once more to get shoes for those who were barefooted and began a long correspondence with the commissary bureau concerning the rationing of the army. Supplies were so scanty and the operation of the Virginia Central Railroad so uncertain that he was compelled to serve warning that he might be forced to retreat nearer Richmond. As he could not leave the army to go to the capital to discuss these matters with Mr. Davis, he requested the President to visit the army, and, during a period of rainy weather from November 21 to November 24, conferred with him on the situation. Lee’s most immediate concern was for the horses, which were almost without forage. He anticipated the loss of many of them from starvation during the winter, and he did not believe that without food they could survive more than two or three days of active operations. The country round about had been stripped almost as bare as the devastated area north of the Rappahannock.

But whether men or mounts survived or perished, Lee had to guard his front against the powerful, warm, and well-fed enemy that might again descend upon him. A little tributary of Mine Run, known as Walnut Run, fifteen miles north-east of Orange Courthouse, was fortified to cover the right flank. Ewell’s corps was extended from that point westward to Clark’s Mountain, where the old lookout was re-established. In Ewell’s absence on account of sickness, this part of the line was entrusted to Early, with particular instructions to study the defensive possibilities of Mine Run. From Clark’s Mountain westward to Liberty Mills, a distance of approximately thirteen miles, Hill’s camps were spread. The cavalry covered both flanks, and as Lee thought it probable Meade would make his next advance from Bealton to Ely’s and Germanna Fords, Hampton’s division on the lower Rapidan was enjoined to maintain a ceaseless watch for an advance in that quarter.

For more than two weeks after the line of the Rapidan was manned, Meade showed no sign of any disposition to assume the initiative except for minor cavalry demonstrations. Then, on the night of November 24, one of Lee’s spies reported that eight days’ rations had been issued the I Corps, and another scout told of suspicious movements by Federal horse in Stafford County. The next morning Stuart’s cavalry was put on the alert, and the army became expectant of a new battle. “With God’s help,” wrote Major Taylor, “there shall be a Second Chancellorsville as there was a Second Manassas.”

Lee’s belief was that his able adversary, in making another thrust, would attempt, on crossing the Rapidan, to advance through the Wilderness of Spotsylvania in the direction of the Richmond and Fredericksburg Railroad. He had already suggested to General Imboden in the Shenandoah Valley that he join with Mosby’s Rangers in operations against the Federal line of communications, and he now prepared to move quickly to the north-east in order to interpose between Meade and his objective. For once the roads favored him, and he had three fair highways almost to Wilderness Run and two nearly to Chancellorsville.

A heavy fog limited vision from the Confederate signal stations early on the morning of November 26, but this lifted as the day wore on, and disclosed the enemy moving in force through Stevensburg toward Germanna Ford. As this was precisely what Lee had expected Meade to do, orders were issued for the Confederate movement to begin during the night. Care was taken to cover both flanks, and a route was selected for the wagon train that would place it where it could either reach the army quickly or retire southward toward the line of the Virginia Central Railroad. At 3 A.M. on the morning of the 27th, Lee left his headquarters near Orange Courthouse and started for Verdiersville. The weather was excessively cold, and icicles formed thickly on the beards of the officers, but Lee was in high spirits, now that there was a prospect of battle. He was quite unconscious of the inward grumbling of his staff that he had started ahead of everyone else and would arrive at his destination ere more seasonable sleepers were astir.

True to these chilly predictions, when Lee reached Verdiersville he found no troops there, but down the road, in a thick pine wood, fires were burning and Confederate cavalry outposts were to be seen. After establishing his headquarters at the Rhodes house, Lee walked down the plank road and found Stuart just rising from beside the fire, where he had slept since midnight with only one blanket. “What a hardy soldier!” Lee exclaimed as Stuart approached. The same thing might have been said of Lee himself, for he had cast aside his cape and wore only his uniform.

In a brief conversation with his chief of cavalry, Lee directed him to cover the roads in the direction of Chancellorsville and Spotsylvania Courthouse, as the enemy was believed to be moving in that direction. Not long after Stuart rode off to look for Hampton’s division, which had not yet come up, General Early reported in person. Ewell’s corps, Early said, was already beyond Verdiersville on the old turnpike, which approximately paralleled the plank road. Lee simply ordered him to continue his advance in the direction of Chancellorsville and to attack any force he encountered Early rode off to direct this movement. He soon sent back word that the cavalry pickets had been driven in and that General Hays, who was leading Early’s own division, had met Federal infantry at Locust Grove, situated on a ridge about a mile and a half east of Mine Run. Assuming that this was a force thrown out to protect the rear of Federals moving eastward from the nearby fords, Lee did not ride forward to reconnoitre in person, but waited at Verdiersville for the arrival of Hill’s corps, which had a long march on the plank road from its encampments.