We can see from this that Boabdil’s life as sultan in the Alhambra was luxurious and pleasurable from a material point of view, but his political landscape was less attractive. Although he ruled exclusively in his capacity as emir, the policy, actions and affairs of state were conducted and influenced by divergent groups and individuals, the most prominent of whom was the vizier, or wazir. Since the emir was above all a military leader whose mission was to defend Granadan Muslims from danger, the military government of territory was more important than civil government. To maintain his personal power Boabdil had to spend a good part of his income on maintaining the garrison and troops on a salary, and he needed to rely on his vizier to act on his behalf in civil matters, although the minister had to obey the superior jurisdiction of the emir, could not interfere in the decisions of religious authorities and did not have any right of succession. The appointment or dismissal of the vizier was the will of the emir, and many of those appointed to the post became personal friends of their masters, such as Boabdil’s vizier Aben Comixa, who served him loyally to the end, in contrast to the viziers of some earlier rulers who were notoriously vicious to their enemies. The vizier had a virtually all-embracing power derived from the trust and friendship of the emir. He conveyed and fulfilled the emir’s orders, organised all administration, drew up decrees and official correspondence, as well as being head of diplomacy and leader of the Granadan part of the army, although the emir held overall jurisdiction and power as military commander.

The qadis, or judges who reviewed civil, legal and religious matters according to Islamic law, were trained in theology at the madrasa in the city, and were entirely independent of the emir. In the late fifteenth century they had all the power of the doctors of Muslim law, the fuqaha, behind them. Both groups could dictate policy on the strength of their opinions, and they were both ferociously opposed to any emir who countenanced concord with or subjection to Castile, which did not augur well for Boabdil. Religion was inseparable from the administration of justice, and the existence of a civil, secular judicial body was unthinkable. So Boabdil ruled surrounded in theory by friendly collaborators in the vizier and the qadis, to which we should add the ever-present pressure groups and unions of interest formed by the lineages, including the Abencerrajes who had supported both Aixa and Boabdil, and also the military who were the masters of physical force. The uniqueness of existence in Granada rested on this social and political edifice.

Looking out from the belvederes of the royal apartments, an abundant city of gardens, groves of trees and private orchards surrounding its walls was laid out before Boabdil , with the inimitable vega beyond. This fertile plain acted as a natural defence for the city as it was a barrier between Granada and the mountains. It was also vital for providing food, and flourished at the hands of Muslims expert in horticulture and irrigation. In common with other Nasrid cities, Granada had intimate contact with its rural surroundings. This was in strong contrast with its Christian conquerors, who scorned the local countryside. City dwellers went to the country for harvest celebrations and festival days, while there was a constant flow of Granadans from the vega entering at the city gates to sell their vegetables and fruit.

Beyond the vega lay the omnipresent frontier. This area of land, known to the Castilians as the banda morisca, the Morisco border, was a vital factor in the material and psychological life of the Granadan state. It is one of the most fascinating features of the war between Christian Spain and Muslim Granada. The Spanish historian Miguel Ángel Ladero Quesada makes a telling point when he writes that this frontier was unusual because it divided a place that had a previous history and identity as Hispania, and separated populations mostly descended from natives of Hispania on both Christian and Muslim sides. In that sense it could not be compared to other medieval frontiers between Christianity and Islam such as Byzantium or the Crusades in areas of the Mediterranean. It was not officially a border between two countries, but in all other respects it might just as well have been, as it separated two cultural systems, two religions, two societies. No independent new culture ever emerged as there was little possibility for coexistence or mixing. The frontier was a precise one, a line or strip marked out by towers and fortresses, a line of demarcation not only geographically but also symbolically. As L. P. Harvey puts it, it was also a frontier of the mind. It was the tangible manifestation of an ancestral confrontation between two worlds which opposed each other from ideological and religious positions that were reciprocally exclusive.

The land frontier that delimited the territory of the Granadan emirate consisted of about 11,600 square miles (30,000 square kilometres) of what is now eastern Andalusia, and it had existed for nearly 250 years when Boabdil became sultan in 1482. The territory was a paradoxical place of peace and also of hostility. There, truces were fulfilled and goods exchanged, while daily hostilities and confrontation created a permanent need for both defence and attack along the border. The truces helped to suspend and defuse large-scale hostilities and ease the pressure of the intense life of frontier coexistence, where at times relations were peaceful and even neighbourly, but mostly consisted of rivalry, violence and reprisal. There were some measures in place for maintaining peaceful coexistence on a daily basis in the form of the juez de frontera, or frontier judge, a kind of arbitrator between Moors and Christians, and usually there was one representative from either side, both of whom resolved the petitions of the opposing group. There were also special frontier police, the fieles de rastro, and exeas, or interpreters, who were indispensable for commerce, in the exchange of captives between the two parties, and as guides for merchants. Often a Christian interpreter let his beard grow and wore Muslim clothes in order to be better accepted by the Granadans. Direct evidence of the vital role played by interpreters is brought to light in a letter written by King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella to Boabdil much later, in June 1488, regarding a number of Moors, as they describe them, who managed to infiltrate the province of Malaga, under Christian command by that time, and who committed some unspecified crimes. The monarchs command Boabdil to make public announcements stating that no Moors should visit these areas without a Christian interpreter, otherwise they would be taken captive.

Castile was perennially the counterpoint to Granada, and nowhere more so than on the frontier. The attitude of the Castilian Christians to the Muslim emirate speaks of a fundamental difference in perception between the opposing sides. Castile perceived Granada as a vassal kingdom whose emirs held illegitimate power because the creation of the Muslim state by Muhammad I was in their eyes an act of vassalage. Granada naturally took a different view, and never accepted its subservience to the Christians. The social and political aspirations of the Christian noblemen of Andalusia largely revolved around the frontier, where many died or were wounded; these showed in their chivalric ideals and in the poetic memory of that unique time recorded in the famous Spanish frontier ballads then and later. The pattern of violence and reprisal provided the opportunity for heroism on the frontier, through the kind of hostility that did not break any truce in force, such as surprise assaults and horseback raids on fortresses and other local places, with the intention of seizing booty, wearing down the enemy and capturing a frontier outpost. These sorties fed a desire for fame and for fulfilment of the ideal of fighting the infidel.

For the Granadans, ribat, which was the obligation to fight on the frontier, was a religious one, and their involvement in frontier warfare was essentially defensive since there was little hope of them ever being able to expand their territory significantly owing to its geographical location. Yet, however seriously both sides might have taken their obligation to fight for their God and for their people, the immediate aim was often the commandeering of a herd of cattle or a recently harvested crop. The frontier fighters developed a way of life which was transferred to the New World discovered by Columbus, where cattle raiding and hard riding formed part of the myth of how the West was won, and was also echoed in the life of the Argentinian gauchos.

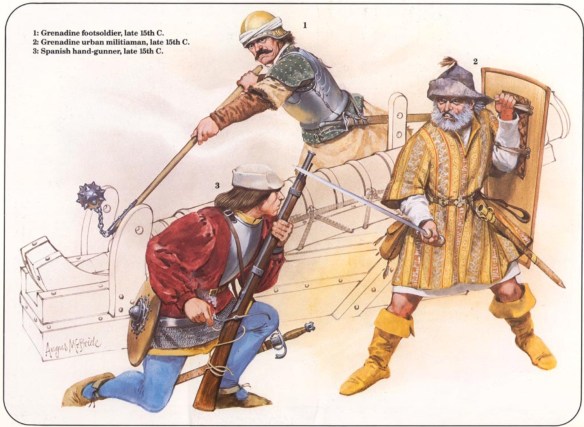

The major preoccupation of Boabdil’s life up to the time he became sultan was the inner discord in Granada and in his own family. But the Christian threat on and beyond the frontier that lurked constantly in the background began to come to the fore in 1482. The Granada campaign now started in earnest. In 1479 the Warrior Pope Julius II had issued a crusading bull calling for war against Granada. This chilling order from the head of the Catholic Church was reissued in 1482, reinforcing the ingrained idea that the war against the Moors was part of the culture of the fighting and ruling classes of late medieval Spain. The popularity of great novels of chivalry such as Tirant lo blanc (Tirante the White) and Amadís de Gaula (Amadeus of Gaul), whose world of valour and often superhuman strength of arms reinforced traditional values, proclaimed the need to restore chivalric ideals among the knights of Spain. The Muslim preoccupation with lineage was to an extent mirrored by the Christian anxiety over limpieza de sangre, or purity of blood. Aristocratic families were desperate to assert their unsullied bloodline going back to the ancient Visigoths. In Castile in particular, being the son of someone of note, an hijodalgo – from which the word hidalgo comes – was an important distinction.

The Christian chroniclers of the war emphasised the idea that their campaign could be vindicated as a reconquest of territory lost a long time ago to the Moors. It was a taking back, a restoration of what was rightly theirs, the overcoming of a wicked political enclave and a holy war against the unbeliever. It was also a positive way of channelling the violence among the aristocracy of Castile which had threatened to ruin the kingdom in recent years. The accounts of those historians are inevitably biased towards the victors, and we have to take this into consideration when we attempt to build up a picture of what really happened. With the exception of the anonymous Arabic Nubdhat and al-Maqqari’s long history, nearly all the accounts of the Granadan war were written by Christians, though it is true to say that they often present the Muslim enemy in a respectful light, and even with admiration at times.

As life on the frontier continued with its raids, skirmishes and minor victories on both sides, the event took place which proved to be the catalyst for a final, focused Christian campaign against Granada. While Boabdil and his supporters were in Guadix in early 1482 plotting the next moves in their plan to set the prince on the Granadan throne, the Christians made the surprise assault on the fortified town of Alhama, when Abu l-Hasan so boldly defended its people against the odds. The success of the Christians in this battle moved the war into a new phase and, as we have seen, Abu l-Hasan was quick to retaliate in successfully defending Loja. But this did not deter King Ferdinand for long. He regrouped his men and resorted to a strategy known as the tala, which consisted of burning and destroying crops. It was a ploy he had used before, except that this time it was in the vega of Granada, very close to the city, and in an area which provided much of its essential grain, fruit and vegetables. It was a dreadful, slow and devastating process, against which the Granadans could do nothing. If their food supplies were destroyed, there could be no hope of survival.

In his territory of the now divided kingdom of Granada, Abu l-Hasan carried on doing what he did best – raiding and attacking frontier outposts. By early 1483, the Christians had decided to try to capitalise on their success at Alhama and invade the large and beautiful coastal area east of Abu l-Hasan’s territory of Malaga, known as the Ajarquía. Their strategy was not entirely clear, other than perhaps to boost their morale, and that lack of clarity of intention was matched by an equal indecisiveness regarding which way they should go. A council of war assembled in the town of Antequera and a long discussion took place. Fears were expressed about the rough mountainous terrain and steep drops which favoured the enemy, and which would be little use to the Christians if they did capture it. In the end they did decide to make a raid, but their fears proved to be well founded, since the local inhabitants led them into a disastrous trap. Pulgar tells us what happened:

The scouts who were entrusted with guiding them along the safest route took them across a mountain track so high and steep that a man on foot would have found it difficult. According to their custom, the Moors kept fires lit all day and all night on the tops of mountains and other high points, as a way of summoning those who lived in those areas. They lay in wait for the Christians and inflicted heavy casualties by raining rocks down on them and firing arrows from the side and rear. As the Christians struggled to extricate themselves, night fell. Fearing they would suffer even greater casualties if they kept on the track, they went back down a deep river valley under a high mountain which the Moors had already climbed. When they saw that the Christians had taken this route they threw rocks and stones down on them, killing many. Some who tried to escape by climbing the cliffs fell to their deaths because in the darkness they couldn’t see any of the footholds. They could hear the war-cries of the Moors, and terrified by the darkness of the night and the rugged terrain, they lost heart and did not know how to escape.

The experienced soldier Rodrigo Ponce de León managed to escape only by taking another man’s horse. Many Christians gave themselves up rather than face the mountainous ravines around them, and quite a number were captured in the countryside by brave Muslim women who came out from Malaga to hunt for them. More than 1,000 prisoners were taken. Pulgar naturally blamed the scouts, although he also criticises the excessive pride of the Christians. Abu l-Hasan did well out of the victory, as the booty won was sent to Malaga to be shared out, but it inevitably ended up in the hands of his officials.

Back in Granada, the news of the Christians’ demoralising defeat reached Boabdil, and his advisers and other noblemen felt that on the back of this, the new sultan should make some kind of sortie into Christian territory to please his people and show his mettle. So Boabdil and his troops left the Alhambra with a great display of power and aplomb, and passed through the towns of Luque, Baena and other areas before returning to Granada, where he was welcomed back joyfully. It was a successful PR exercise, and gave Boabdil a sense of his own strength and responsibility. The mood was high. From the shelter of the palatine city he could survey his domain, the still prosperous city below him. His father was out of the way in Malaga, and in spite of the ruined crops in the vega, supplies still arrived from outlying towns and villages. The enemy was demoralised and the sultan, aged twenty-one or twenty-two at the time, was persuaded to undertake a more daring plan for his next military outing. Little did he know that he was to meet his nemesis.