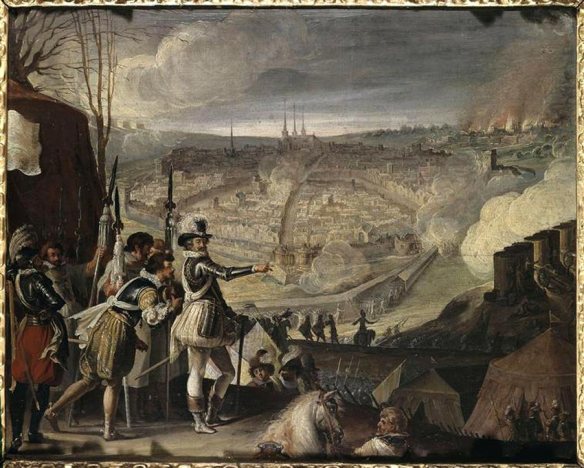

Henry IV before Amiens.

Siege of Amiens 1597 showing the English positions (left) & French positions.

Henri was King of France, but only in name. Most of the country was ruled by warlords, and everywhere the nobles robbed the bourgeois and harried the peasants, while the countryside swarmed with bandits. The League proclaimed as king Henri’s uncle, the aged Cardinal de Bourbon, and struck coins in the name of ‘Charles X’; but their real champion was the Duc de Mayenne (Guise’s brother) who secretly hoped for the throne. A mere sixth of France supported Henri. His army dwindled every day—not many Catholics would fight for a heretic King who had been excommunicated. His only chance was to be a Politique, to appeal to those who preferred peace to religious war. Some years before, he had written to a friend, ‘those who follow their conscience belong to my religion—my religion is that of everyone who is brave and true.’ But while the Baron de Givry might fling himself at Henri’s feet, crying, ‘You are the King for real men—only cowards will desert you’, there were not many men like Givry.

Meanwhile, Henri withdrew to Normandy with 7,000 troops, from where he could control the districts on which Paris depended for food, setting up his headquarters at Dieppe. Here he could obtain supplies and munitions from England. Mayenne pursued him, with 33,000 men. The odds were nearly five to one, and Henri’s staff advised him to sail for England. Instead the King prepared an impregnable position. The road from Paris approached Dieppe through a marshy gap between two hills—on one side was the castle of Arques, on the other earthworks and trenches. Henri placed his arquebusiers and Swiss pikemen in the trenches and drew up his cavalry behind them; heavy cuirassiers armed with pistols but accustomed to charging home with the sword.

The Catholic cavalry were old-fashioned lancers who charged in widely spaced lines. Their commander, the Duc de Mayenne, was a strange figure, enormously fat, too fond of food and wine, gouty and tortured by venereal disease, who passed his days in a sluggish torpor, frequently retiring to bed. His staff were as idle and unbusinesslike as their commander. None the less, he lacked neither ambition nor courage.

The morning of 21 September 1589 was misty. When Mayenne attacked the trenches in the Arques defile, the mist prevented the castle’s guns from firing. The Catholic pikemen overran Henri’s first line of trenches and the Catholic cavalry attacked on both flanks. When his front was on the point of disintegrating, Henri galloped up, shouting ‘Are there not fifty noblemen of France who will come and die with their King?’ His cavalry held the enemy—the Royalist foot rallied. Then the mist lifted and the castle batteries opened fire. The Leaguers withdrew hastily and Henri retook all the lost ground. Mayenne realized that he was facing a most formidable general. Some days later, news came that reinforcements were on their way to Henri—more Huguenot troops and an English expeditionary force. After another halfhearted engagement, the Duke withdrew.

Having taken the measure of his opponent, Henri was anxious to bring him to battle again. As bait he laid siege to Dreux. Mayenne advanced to its relief with 15,000 foot and 4,000 horse, and on 14 March 1590 engaged the King at Ivry. Henri had 8,000 infantry and 3,000 cuirassiers. A white plume in his helmet and a white scarf round his armour, he prayed before his troops—then he told them that, whatever happened, they must follow his white scarf. In the centre, he led his cuirassiers to crash into Mayenne’s lancers, through whom they hacked and pistolled their way. All along the line the Royalists hurled back the enemy cavalry until they disintegrated, fleeing, abandoning their infantry to be shot down by Henri’s arquebusiers. In his flight, Mayenne ordered the bridge at Ivry to be broken down behind him, cutting off many of his men from any hope of escape. The King ordered his exultant followers to spare Frenchmen but to give foreigners no quarter. Three thousand Leaguer foot and 800 cavalry died—nearly a hundred standards were taken.

In May he besieged Paris with 15,000 men, but the capital remained fanatically Catholic—even monks and friars took up arms. Rather than shed Parisian blood, Henri decided to starve the city into submission. (He is said to have passed his time debauching two young nuns, whom he afterwards made abbesses.) By July Paris was starving, horribly. There were cases of cannibalism—children were chased through the streets. People ate dead dogs, even the skins of dogs, together with rats and garbage. Some made flour from bones; those who ate it died. Thirteen thousand perished of hunger. At midnight on 27 July the King launched a general assault on the suburbs, but it was beaten back; despite its sufferings, Leaguer Paris was not prepared to surrender to a heretic King. Early in September it was relieved by the Duke of Parma, who ferried food across the Seine to the stricken city. Disconsolately the King withdrew, to winter in northern France. Many Royalist squires rode home.

It was in these gloomy days that Henri met Gabrielle d’Estrées. She was seventeen (Henri was thirty-seven), the daughter of a Picard nobleman, a plump, round-faced pink and white blonde who liked to dress in green. Gabrielle already had a lover, the sallow-faced Duc de Bellegarde (known as feuille morte—dead leaf). Rivalry drove the King into a frenzy. He showered letters on his ‘belle ange’—‘My beautiful love, you are indeed to be admired, yet why should I praise you? Triumph at knowing how much I love you makes you unfaithful. Those fine words—spoken so sweetly by the side of your bed, on Tuesday when night was falling—have shattered all my illusions! Yet sorrow at leaving you so tore my heart that all night long I thought I would die—I am still in pain.’ He wrote a poem, Charmante Gabrielle, and had it set to music. Eventually the affair went more smoothly. In the autumn of 1593 Gabrielle found herself enceinte with the King’s child, the future Duc de Vendôme.

Meanwhile, after the setback at Paris, Henri’s star had begun to rise again. In the summer of 1591 he was reinforced by English troops. For a time these were commanded by Queen Elizabeth’s young favourite, the Earl of Essex, to whom Henri showed himself especially amiable. Sometimes relations were strained: Sir Roger Williams, being rebuked for his men’s slow marching pace, snapped back that their ancestors had conquered France at that same pace. Even so, many Englishmen took a strong liking to Henri IV. In 1591 Sir Henry Unton, the English ambassador, wrote of him: ‘He is a most noble, brave King, of great patience and magnanimity; not ceremonious, affable, familiar, and only followed for his true valour.’

Sully tells us that Henri’s life on campaign was so exhausting that sometimes the King slept in his boots. Unton grumbled, ‘we never rest, but are on horseback almost night and day.’ None the less, Henri continued to hunt whenever possible.

The League was splitting into many factions. The Cardinal King, ‘Charles X’ had died in 1590, since when they had been unable to agree upon even a nominal candidate for the throne. The most formidable Catholic contender was the Infanta Isabella, daughter of Philip II of Spain—Guise, son of the murdered Duke, was to be her consort.

In November 1591 the Royalists beseiged Rouen. Henri, hearing that Parma was on his way to its rescue, galloped off with 7,000 cavalry to stop him. On 3 February 1592, at Aumâle, he unexpectedly made contact with the Spaniards and had to beat a hasty retreat after being wounded by a bullet in the loins; he was carried in a litter for several days. Unton commented gloomily, ‘We all wish he were less valiant.’ Parma relieved Rouen in April. However, he and Mayenne were trapped by Henri at Yvetot. When all seemed lost for them, Parma—who had been wounded—rose from his bed and evacuated his troops over the Seine by night. This great general then returned to the Low Countries where he died at the end of the year, his wound proving mortal.

One must admit that Henri IV lacked calibre as a soldier, compared with Parma. Though capable of fighting a defensive battle, as at Arques, the King was primarily a cavalry man—all his victories were won by the charge. His instincts as a captain of horse always came before his duty as a commander.

During 1592 Henri, the League and Philip II accepted a stalemate. The Tiers Parti, a combination of Politiques and moderate Leaguers, now asserted itself. Their solution was that Henri should turn Catholic. More and more Huguenots were willing to settle for a Politique monarchy—many urged the King to let himself be converted. After carefully counting his followers’ reactions, Henri, in white satin from head to foot, was received into the Roman fold at Saint-Denis, on 23 July 1593. This conversion has too often been seen as an act of cynical statesmanship, summed up in the phrase ‘Paris vaut bien une messe’ (there is no proof that he ever said it). In fact Henri wept over the gravity of the step. Since childhood his personal beliefs had been fought over by the kingdom’s most persuasive theologians, and he must have become hopelessly confused. Within a fortnight, towns all over France were declaring for Henri, and on 25 February 1594 he was crowned King in Chartres Cathedral. The impact upon France was extraordinary—Henri’s putting on the Crown was accepted as both sacramental confirmation and seal of legality.

On 18 March Henri entered Paris, sold to him by its governor, the Comte de Cossé-Brissac. The same afternoon the Spanish troops marched out of Paris. Henri watched them, saying, ‘My compliments to your King—go away and don’t come back.’

The warlords still controlled most of France—Mayenne Burgundy, Joyeuse the upper Languedoc, Nemours the Lyonnais, Epernon Provence, and Mercoeur Brittany. But the bourgeoisie rallied to Henri. Town after town rebelled against the magnates; at Dijon, led by their mayor, armed citizens overcame Mayenne’s troops and handed the town over to the Royalists.

Paris was still dangerous. Early in 1595, a young scholar, Jean Chastel, attacked Henri with a knife. Always agile, Henri recoiled so quickly that he escaped with only a cleft lip and a broken tooth.

At the beginning of 1595 Henri formally declared war on Spain. He had not done so before, to avoid the onslaught of Philip II’s full military might, which was still directed against the Dutch. Soon the Spaniards were invading France on five fronts. In June Henri, operating in Burgundy, nearly lost his life in a cavalry skirmish at Fontenay-le-Français. With a small force of cavalry he found himself surrounded by the entire Spanish army. An enemy trooper slashed at him and was shot down only just in time by one of Henri’s gentlemen. Luckily, reinforcements came up and the Spaniards withdrew. Henri wrote to his sister Catherine, ‘You were very near becoming my heiress.’

In September 1595 Clement VIII at last agreed to give Henri absolution (officially he was still excommunicated). Six days later Mayenne negotiated a truce with Henri; in return for his submission he received three million livres and the governship of the Ile de France. Soon, of the warlords, the Duc de Mercoeur in Brittany alone remained. Elsewhere every important French city had recognized Henry IV by the summer of 1596.

But Philip II continued the war implacably. Henri was desperate for money: in April 1596 he wrote to Rosny (the future Duc de Sully) that he had not a horse on which to fight nor a suit of armour. ‘My shirts are all torn, my doublets out at elbow, my saucepan often empty. For two days I have been eating where I can—my quartermasters say they have nothing to serve at my table.’ The King summoned the old feudal Assemblée de Notables to meet at Rouen in October 1596—nineteen from the nobility, nine from the clergy and fifty-two from the bourgeoisie. He invited them to share the task of saving France, in a tactful and flattering speech, and the necessary supplies were voted. Even so the war was far from won. In 1597 Amiens, capital of Picardy, was captured by the Spaniards. It was a severe loss, as not only was the town the centre of Franco-Flemish trade, but also a supply depot filled with munitions. Henri in person led an army to recapture it. ‘I will have that town back or die,’ he promised. ‘I have been King of France long enough—I must become King of Navarre again.’

During his siege of Amiens, Henri reorganized the army. He placed the three veteran corps of Picardy, Champagne and Navarre (also known as Gascony) on a permanent basis, together with that of Piedmont and new regiments from the northern provinces, each of 1,200 picked musketeers and pikemen. There were also the Royal Guards and the various regiments of mercenaries, Swiss and German. His 4,000 Gendarmes d’Ordonnance provided the heavy cavalry.

Amiens surrendered on 25 September. Elsewhere the Spaniards were failing. The Dutch, still fighting the Spanish, were increasingly successful. Another Spanish Armada, destined for Ireland, was destroyed by storms. In March even Mercoeur surrendered. King Philip, in failing health, despaired and, on 2 May 1598 a treaty was signed at Vervins, by which France retained the frontiers of 1559 and regained any towns occupied by the Spaniards. (Queen Elizabeth of England was so furious that she called Henri the Anti-Christ of ingratitude.)

Henri had also taken steps to ensure peace at home. The Edict of Nantes, promulgated in April 1598, gave the Huguenots liberty of conscience and guaranteed their safety with 200 fortified towns maintained at the Crown’s expense, though defended by their own Protestant garrisons. The Edict was not quite the triumph of common sense over bigotry that it seems to modern eyes. In reality it was little more than an armed truce. Protestant France could muster 25,000 troops led by 3,500 noblemen who constituted an experienced and highly professional officer corps. An English observer, Sir Robert Dallington, noted: ‘But as for warring any longer for religion, the Frenchman utterly disclaims it; he is at last grown wise—marry, he hath bought it somewhat dear!’ France could simply not afford another civil war. Even so Henri had to bully the Parlements into registering the Edict.

Henri IV was now undisputed King of a France which was at peace for the first time for nearly half a century. At last he was able to enjoy Paris. He acquired new friends, like the fabulously rich tax farmer, Sebastien Zamet, an Italian from Lucca, who had begun his career as Catherine de Medici’s shoemaker and then made his fortune as court money-lender. The King often dined and gambled or gave little supper parties for his mistresses in Zamet’s hôtel in the Marais. Gabrielle became a familiar figure in the capital. She accompanied the King everywhere; they rode together hand in hand, she riding astride like a man, resplendent in her favourite green, her golden hair studded with diamonds; she presided over the court like a Queen. As tactful and kindly in manners as she was warm-hearted and generous by nature, Gabrielle had the miraculous gift of making no enemies. She had born Henri several children, notably César whom the King made Duc de Vendôme. Gabrielle was given increasingly greater rank, eventually becoming a Peeress of France. Henri’s love deepened every day. Eventually he decided to marry her. In token of betrothal he gave her his coronation ring, a great square-cut diamond.

Henri left her briefly in April 1598, when she was again big with child. Her labour began on Maundy Thursday, accompanied by convulsions. On Good Friday, her stillborn child was cut out of her; she suffered such agony that her face turned black. She died the following day, of puerperal fever. Henri buried her with the obsequies of a Queen of France—for a week he wore black, and then the violet of half-mourning. He wrote to his sister, ‘The roots of love are dead within me and will never revive.’

Perhaps fortunately for his sanity, he was soon busy with Savoy. Its Duke, Charles Emmanuel, who dreamt of restoring the ancient Kingdom of Arles, delayed the surrender of Saluzzo and intrigued with Henri’s courtiers; there was even a plot to poison the King. In late 1600 Henri invaded the Duchy. Snow made it a difficult campaign and Henri complained of the hardship—‘France owes a lot to me, for what I suffer on her behalf.’ By the peace of Lyons, signed in January 1601, Henri gained Savoyard territories on the Rhône which all but blocked communications between the Spanish Netherlands and Spain’s possessions in northern Italy. It was the end of Henri’s career as a soldier. Few monarchs have handled a pike or pistolled their way through a cavalry mêlée with such gusto.