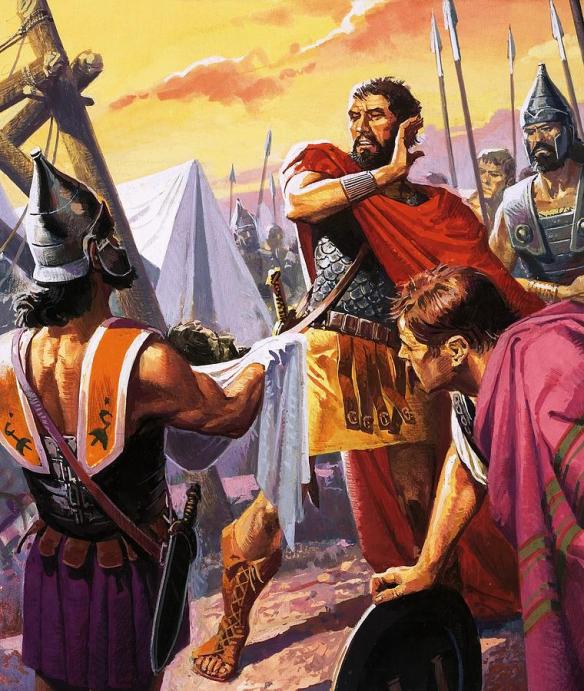

Hannibal presented with the head of his brother Hasdrubal.

When Hannibal left Spain for Italy, he placed his younger brother Hasdrubal in command of the Carthaginian-controlled portion of the country. Hasdrubal was tasked with holding southern Spain, upon whose vast mineral wealth and manpower reserves Carthage depended to fuel the war against Rome. For ten years, Hasdrubal kept the Spanish tribes nominally under his control and the Romans at bay. Then in 208 B.C. Hannibal sent word to his brother to bring reinforcements to Italy. Hasdrubal was the equal of Hannibal in all respects: character, courage, skill, and ability to command. He was, as the Roman historian Livy commented, “a son of Hamilcar Barca, the thunderbolt,” and as dynamic and experienced a leader in battle as Hannibal. Hannibal in Italy was trouble enough for the Romans, but now the second son of the thunderbolt was about to bring another army of mercenaries and elephants over the Alps to reinforce his brother.

Polybius had similar praise for Hasdrubal, characterizing him as a brave man, to be admired for his abilities as a commander, and not dismissed out of hand because he lost and died at the battle of the Metaurus. Hasdrubal stands out because he kept the Romans at bay in Spain for ten years, brought his army over the Alps intact, increased its size with Gauls, and nearly reached his brother. He could see beyond the short-term rewards of victory in battle, glory, and profit and formulated a contingency if things, as they often do, should go wrong. This was something that Polybius found to be a rare and valuable characteristic in leaders of his day.

Both Polybius and Livy praised Hasdrubal for having made it over the Alps with his army—more rapidly than Hannibal, and with significantly fewer losses. It was an accomplishment on a par with Hannibal’s but has been overshadowed and relegated to the footnotes of history. Hasdrubal moved quickly through Gaul and over the Alps, due perhaps to better weather conditions. The Gauls probably allowed Hasdrubal, with nearly twenty thousand soldiers and a contingent of elephants, to move through their territory safely, but we do not know for sure if the passage was entirely without difficulties. Hasdrubal reached Italy more quickly than his brother had expected, which may account for the coordination problems that developed between them.

The Roman army was waiting for Hasdrubal at the Metaurus, a river that begins in the heights of the Apennine Mountains and flows east into the Adriatic Sea at Fano, just north of the modern-day port of Ancona. The Romans won that day and their victory was the turning point in the war. The Metaurus is one of the greatest battles in ancient history, yet it has been given remarkably little attention by scholars, overshadowed as it is by Hannibal’s crossing of the Alps, and his victories at Trasimene and Cannae. Hasdrubal’s defeat and death were significant because they sealed Hannibal’s fate in Italy and condemned him to lose the war. The Romans won at the Metaurus because of the competence and effective coordination of the two consuls in command, Gaius Claudius Nero and Marcus Livius Salinator. Of the two, Nero is probably the unsung hero of the battle, and, in some respects, of the Second Punic War. Because of his initiative, boldness, and drive, he turned the tide of the war in Rome’s favor and, like Hasdrubal, he has been relegated to history’s footnotes. Claudius Nero took a gamble and made a bold move, which deceived Hannibal and defeated Hasdrubal.

The Romans needed competent leaders, one to deal with Hannibal in the south and another to stop Hasdrubal in the north. Many of Rome’s most experienced commanders had been killed in prior battles, including the Scipio brothers in Spain. It was the law of Rome that one of the two consuls elected each year to command the armies of the republic had to come from the lower plebeian class and one from the aristocratic patrician class. The patrician candidate for office in 208 B.C. was Claudius Nero, whose descendant some two hundred years later would become the infamous Julio-Claudian emperor. Claudius Nero, whose cognomen or nickname can mean the powerful one or the dark one, depending on the context, was an experienced commander who had fought against Hannibal in Italy and Hasdrubal in Spain.

The plebeian candidate for the consulship was Marcus Livius Salinator, nicknamed the salt man. Salinator had commanded Roman forces in Illyricum but had been censured and then exiled for a term for using his position to enrich himself. Because Rome was critically short on experienced commanders, he was allowed to return and run for the consulship. The two men hated each other because Nero had been one of Salinator’s most vocal and strident accusers when he came to trial. After the election, when the senate awarded them their commands and sought to reconcile them, Salinator rebuffed the overture and commented it would be best if they remained enemies. The hope of Rome, now at its most perilous hour since Cannae, rested on two men who detested each other. Salinator took command of the forces in the north, tasked with blocking the Alpine passes through which Hasdrubal had to pass, while Nero was given command in the south against Hannibal. But Hasdrubal, in command of a force now estimated to have grown to some thirty thousand, had moved far more quickly than expected. He came down from the Alps and was on the plains of Italy before Salinator could put his own forces in place to stop him.

In the south, Nero moved his army of forty thousand to Venusia in Apulia, looking for Hannibal, who began playing a game of cat and mouse with his Roman adversary. There were minor skirmishes where Hannibal’s soldiers apparently suffered more casualties than the Romans. The fact that Hannibal avoided engaging Nero leads to speculation that his army may have been weakened considerably by this point in the war. Hannibal eventually retreated farther south on the Italian peninsula to Metapontum, where the ranks of his army were increased with new recruits from Bruttium enlisted by his nephew Hanno. Only when his army was reinforced did Hannibal move it back to Venusia, where he waited for Nero to make his next move. Hannibal had become uncharacteristically passive.

In the north, Hasdrubal avoided the Roman army, and instead of crossing the Apennine range by the same route Hannibal had taken earlier, he moved by way of Bologna, directly to Ariminum (Rimini) on the Adriatic coast. Ariminum had been established by the Romans in 268 B.C., shortly before the First Punic War, as the terminus for the recently completed Via Flaminia, an ancient version of a superhighway. The highway led from Rome, over the Apennine Mountains, to the east coast of Italy. At Ariminum, Hasdrubal posed a direct threat, as he was now, by way of the Via Flaminia, less than two hundred miles from the city. The Roman senate, on the advice of Nero, sent an army to block the route. As Hasdrubal moved south along the Adriatic coast looking for his brother, another smaller Roman army, led by the praetor Lucius Porcius Licinius, the pig man, moved into position and began to shadow him from the north.

Anxious to establish contact with his brother, Hasdrubal sent six horsemen south along the coast with orders to find him. Riding day and night, the couriers covered nearly four hundred miles from Ariminum to just north of Tarentum without being detected. Just short of reaching Hannibal, who had retreated to the coastal city of Metapontum, their luck gave out when they came upon a detachment of Roman soldiers who were foraging in the countryside for supplies. Captured, they were taken to Nero, who ordered them tortured until they revealed the details of their mission as well as the size, composition, and route of Hasdrubal’s army.

Nero was now faced with a dilemma. Could he trust the information that had fallen into his hands by luck—a gift from the gods—and act on it? Or was this a Carthaginian trick intended to lure him into the kind of trap Hannibal was famous for setting? While everything about these messengers seemed genuine, down to the fact that their horses were worn out from days of hard riding, the year before, a Roman force commanded by Marcellus, one of Rome’s best generals, was ambushed on the border between Apulia and Lucania. Marcellus was killed in the fighting, and Hannibal used the consul’s signet ring to forge documents in an effort to retake the city of Salapia. The attempt failed when the Roman garrison commander became suspicious about the authenticity of the documents.

Nero put his reservations aside and acted decisively to stop Hasdrubal from reaching his brother. Taking a portion of his army, essentially his best soldiers, he led them north in a forced march to reinforce Salinator at the Metaurus River. Nero’s plan was to quickly defeat Hasdrubal and return south before Hannibal even knew he had left. It was a bold gamble with high stakes. If Hannibal learned that Nero was gone and attacked his weakened army in the south, it would be a disaster. Then there was the question of whether Nero’s soldiers could be force-marched over such a long distance, fight a major battle, and then force marched back to fight again. How much could human endurance be taxed? Nero sent couriers to Rome to advise the senate to send a legion from Capua to reinforce the soldiers securing the Via Flaminia and then assembled his expeditionary force; six thousand infantry and one thousand cavalry. Marching them day and night, north from Tarentum, through the center of Italy, they arrived where the Metaurus River enters the sea at Fano.

Nero and his army covered the distance in a remarkable seven days. Each soldier carried only the bare minimum—mainly his weapons. Messengers were sent ahead of the army to mobilize the people who lived along the route to prepare food and provide supplies for the soldiers as they passed. In that way, the army could move without being encumbered by baggage, supplies, and camp followers. As Nero’s army moved north, volunteers along the route, moved by patriotism and caught up in the emotions of the moment, joined them, swelling their ranks. What Nero was doing went against Roman law. As a consul, he was forbidden to leave his assignment without senatorial permission. Recognizing the potentially devastating consequences of the Carthaginian brothers joining forces or attacking Rome from two different directions, and the need for decisive action, Nero circumvented the law and acted on his own volition.

Livius Salinator, on the other hand, was taking a very cautious approach relative to Hasdrubal and his army. He allowed the Carthaginian army to cross the river and move south along the coast, without engaging them. With the army of Licinius behind him, Hasdrubal camped just a half-mile or so to the north of Livius. Nero arrived with his army late at night and led his soldiers into the Roman camp quietly so as not to raise an alarm among Hasdrubal’s sentries. Nero was constantly worried about Hannibal, and despite a long and tiring march, he insisted on fighting Hasdrubal the next day so he could return south as quickly as possible.

The next morning, Hasdrubal awoke to find two Roman armies in front of him and one behind. Overwhelming forces were converging on him at the Metaurus, and this caused him to conclude that Hannibal might already have been defeated in the south. How else could the Romans have been able to bring together so many soldiers against him in the north? Hasdrubal remained safely within his camp and pondered his options. The rest of the day passed without event, as Salinator and Licinius, in spite of Nero’s pressure for them to engage in battle, refused to advance on Hasdrubal’s fortifications. Nero argued that they could not remain passive, waiting for Hasdrubal to make the first move. All three recognized the urgency of the situation and that time was crucial. Once Hannibal learned that the Roman army in southern Italy was without its commander and weakened in number, he was sure to attack it. The only option open to the Roman commanders was to move quickly against Hasdrubal, destroy him, and release Nero to return south.

Hasdrubal on the other hand had no desire to engage the Roman armies. His mission was to reach his brother with his army intact, so when nightfall came he led them out of camp with the intent of recrossing the river and retreating north as quickly and quietly as he could. Once safely over the Metaurus and well away from the Romans, Hasdrubal planned to try once more to establish communication with Hannibal even though he had only a vague idea of where he might be or even if he was still alive. As the night wore on, Hasdrubal’s problems multiplied. His local guides deserted him, leaving him lost in the darkness, trying to find a safe place for his army to cross the swiftly flowing river. A combination of melting snows from the nearby Apennines and spring rains had caused the river to flood, trapping his army on the south shore as his scouts frantically searched up and down the riverbank in the darkness for a place to cross. Many of the Gauls began drinking and in short order became disorderly. Like most Carthaginian armies, Hasdrubal’s was a mix of cultures and included the same Iberians, Ligurians, Gauls, and Africans as Hannibal’s army.

The first light of morning found Hasdrubal’s army in disarray. It was trapped with its back against the banks of the flooded Metaurus, and there were three consular armies converging on it. When the Roman commanders realized Hasdrubal was cornered, they moved their infantry up into position. Hasdrubal’s cavalry, the one section of his army that was superior to the Romans and on which he depended heavily, was essentially useless in the confined and hilly countryside around the Metaurus. In a bad position and with no alternative left, Hasdrubal gave up looking for a crossing point and ordered his army to turn and prepare to face the advancing Romans. How many soldiers clashed that day is uncertain, but numbers given by the ancient sources tend, as they usually are, to be underestimated, inflated, or contradictory. The Greek historian Appian, for instance, writes that the Carthaginian force numbered forty-eight thousand infantry, eight thousand cavalry, and fifteen elephants. Livy claims that there were more than sixty-one thousand slain or captured Carthaginian soldiers at the end of the battle and still more who escaped the slaughter. Those numbers indicate an army of far more than Appian’s fifty-six thousand. Polybius reported that ten thousand of Hasdrubal’s men were killed in the fighting versus only two thousand Romans.

Hasdrubal’s army probably numbered thirty thousand including his Gauls, and Livius had roughly the same number. The praetor Licinius commanded an additional two legions, probably ten thousand men, so between them the Roman army might have come to forty thousand including their Italian allies. However, the numbers of the allied contingents fighting with the Romans could have been lower, since some of the confederation members in central Italy, weary with the long and indecisive war against Hannibal, had begun to refuse Roman demands to provide auxiliaries and to pay additional war taxes. Adding Nero’s seven thousand troops to the Roman mix, what is certain is that Hasdrubal and his Carthaginians were outnumbered at the Metaurus.

When Hasdrubal’s army turned to face the Romans, his right flank, where he placed his best horsemen, was pressed against the river while his left flank was in hilly terrain, which proved to be a mixed blessing. Hasdrubal’s most experienced and reliable troops, his African and Iberian infantry, were placed on the right flank as well—the section of the battle line where Hasdrubal now placed all his hope for a victory. The center was composed of Ligurians, who, though not as skilled and well trained as the veterans on the right-flank, could be savage fighters in short bursts of combat. Hasdrubal intended for them to absorb the initial Roman assault and keep his center together until the Africans and Spaniards could turn the Roman flank and carry the day.

On his left, Hasdrubal placed the Gauls, his least reliable soldiers, who would be protected by a deep ravine in front of them and hills behind them. By this point, many of them were, according to Polybius, “stupefied with drunkenness.” Hasdrubal had ten elephants, which he used to reinforce the center. However, once the fighting began, the animals quickly became a liability. Frightened by the din of battle, many panicked, and while some charged the Roman line, others turned on their own soldiers. Six elephants were killed and the remainder ran off the field later to be captured or killed by the Romans.

Licinius deployed his infantry directly in front of Hasdrubal’s Ligurians, while Salinator took command of the Roman cavalry on the left flank and Nero positioned himself on the right facing the Gauls. The battle commenced with the Roman left flank charging the Carthaginian right, followed by the advance of the Roman center. The outnumbered Carthaginian horsemen fell back while their center held its ground. Finally, overcome by sheer numbers, the center began to give way. Nero tried to attack the Gauls, but the hilly terrain and the ravine made it difficult for his troops to reach them. Then he made a decision that changed the course of the battle. Taking roughly half a legion with him, Nero broke off the attack and led his troops behind the Roman center to strike hard at the Carthaginian right flank. The Carthaginians broke ranks under the assault, and, with Hasdrubal trying in vain to force them back into the fight, their line disintegrated. Panic ensued, followed by desertions. The Romans chased the fleeing Carthaginians, meeting almost no resistance, and according to the ancient sources this is where most of the casualties among Hasdrubal’s soldiers occurred. The Carthaginian center, now in disorder, faced a three-pronged attack: Licinius from the front, Livius and Nero from the right. Hasdrubal, seeing that there was nothing more he could do, and presumably doubtful of his own prospects of escape or simply unwilling to be taken captive, charged into the thick of the fighting to meet a warrior’s death.

The Romans severed Hasdrubal’s head from his body and brought it to Nero as a trophy. Nero ordered it placed in a sack and given to a courier with instructions to ride south, find Hannibal, and throw the head into his camp. This was barbaric and contrary to Hannibal’s honorable treatment of Roman officers who had died in battle at Trasimene, Cannae, and even in southern Italy. He had been scrupulous in his treatment of their bodies, giving the dead burial with full military honors and often sending their ashes and personal effects back to Rome. Nearly a decade had passed since Hannibal had last seen his brother, and when the head was brought to him, he recoiled at the sight and groaned. The severed head was the harbinger of worse things to come. The war had turned.

Nero ordered the Carthaginian prisoners executed except the most prominent among them, who could be held for sizable ransom. The success of the legions at the Metaurus filled the Romans with hope and gave them confidence that Hannibal could not remain in Italy much longer. Nero changed the course of the war, forcing Hannibal to retreat into the most southern portion of Italy, Bruttium (Calabria), where he remained isolated until he was recalled to North Africa four years later.

With Hasdrubal’s defeat, the war in Italy was essentially lost for Hannibal. Any chance he had of building a force strong enough to even bring the Romans to the conference table was gone. With a Roman naval presence off the coast of Sicily, Hannibal’s chances of reinforcements reaching him from North Africa by sea diminished, and the war in Italy became a sideshow compared to the larger conflict that was now being waged in Spain and soon to reach North Africa. With Hannibal confined to Bruttium, the next four years were ones of relative inactivity in Italy—except for a second attempt to reinforce Hannibal which occurred in in 205 B.C.

This attempt was made by Hannibal’s youngest brother, Mago, who, like Hannibal and Hasdrubal, was dedicated to the struggle against Rome. Mago was an experienced and competent commander who had crossed the Alps with Hannibal in 218 B.C. and was largely responsible for the victory over the Romans at the Trebbia. He distinguished himself at Cannae and later raised additional troops for Hannibal in Bruttium. Mago was sent to Carthage to report on the victory at Cannae and then to Spain in 215 B.C., where, along with his older brother Hasdrubal and another Hasdrubal, son of Gisco, he conducted the war against the Roman commanders Gnaeus and Publius Scipio (215–212 B.C.). When the Romans launched a major offensive in 211 B.C., Mago was instrumental in their defeat and the subsequent deaths in battle of both Scipios.

In the summer of 205 B.C., Mago left Spain for Italy. Instead of attempting another overland trek and Alpine crossing, he chose a sea route leaving a flotilla of some thirty warships and fourteen thousand soldiers on board. Since Hannibal was confined to the extreme tip of southern Italy on the Adriatic coast, reaching him by sea from Spain would have been nearly impossible. The journey would have been too long and dangerous, both because of the risk of storms and the patrolling Roman navy. Instead, Mago chose to hug the Ligurian coast and landed at Genova (Genoa). From there, he moved overland into northern Italy and, like Hasdrubal, recruited as many Ligurians and Gauls as possible to supplement his army. Since Roman armies controlled both sides of the Apennines and blocked the routes south, Mago and his army remained in northern Italy for the next two years, conducting largely guerilla operations. Then, in the summer of 203 B.C., outside of Milan, the Romans forced Mago into a decisive battle. With a force composed of Numidian and Spanish cavalry, infantry, and elephants, supplemented with Ligurians and Gauls, Mago engaged four Roman legions. During the battle, he was badly wounded in the thigh and retreated to Genova and the safety of the ships that awaited him there.

At Genova, messengers from Carthage were waiting with orders for him to return with his army to North Africa. Mago left behind an officer named Hamilcar with a small force to continue guerilla activities against the Romans in northern Italy. Mago died at sea from his wound, just as his fleet passed the island of Sardinia. Hannibal was confined to a narrow area in Bruttium between the Adriatic coast and what today comprises a series of Italian national parks known as the Sila. Crotone is where Hannibal chose to reside—a Greek city famous for philosophers like Pythagoras and athletes like Milo, the Olympic champion and most renowned wrestler in antiquity. In luxury, cultural refinement, and amusement, Crotone was the equal of Capua, and it was there that Hannibal spent the next two years, 205 B.C. until 203 B.C., while the Romans shifted the focus of the war to Spain and North Africa. Isolated, with one brother dead and another one about to die, his forces considerably diminished in numbers, and resources scarce, Hannibal was no longer driving the war but forced to sit on the sidelines and await developments.

To help keep Hannibal contained, a Roman army under the command of the young Scipio moved from Sicily across the Strait of Messina into southern Italy and captured the Greek port city of Locri, just south of Crotone. The port had been important to Hannibal earlier in the war, and even though he launched a counterattack, he was unable to retake the city. A few miles south of Crotone is Cape Lacinium, or as it is known today, Capo Colonna. Among the sparse ruins on its shores is a solitary marble Doric column that looks out over a vast and desolate sea and gives its name to the present-day cape. That column is all that remains of a once magnificent temple built by the Greeks to honor the goddess Juno Lacinia. Among the most prized treasures of the temple was a column made of gold, which Hannibal allegedly probed to determine if it was solid or merely coated. When he discovered it was solid, he contemplated having it melted and cast into ingots or bricks for his personal use until the goddess came to him in a dream and threatened to take away his one good eye if he dared to desecrate her temple.

It was at this temple, at the end of his campaign, that Hannibal allegedly had a bronze plaque erected. It was inscribed in Greek, the universal language of the ancient world at the time, and in Hannibal’s native Punic. On that plaque Hannibal recounted his exploits in crossing the Alps, his battles in Italy, the size of his army, and the numbers of men he had lost. Such tablets, or as the Romans called them, res gestae, were commonplace in the ancient world. They were personal monuments of sorts to the ambitions and egos of important men. While Hannibal’s tablet has never been found and there are only literary references to its existence, it has given rise to speculation that he had come to regard himself as a king, perhaps the regent of southern Italy, and the plaque was left behind so posterity would not forget his accomplishments, victories, and aspirations.

At the same time, that plaque can be interpreted as Hannibal’s tacit acknowledgment that the war in Italy had ended and he no longer had the manpower or the resources to take on the Roman armies. His Macedonian ally, Philip, had failed to deliver, and the last straw came when some eighty Carthaginian cargo ships trying to reach him with provisions were blown off course by a storm and captured by the Romans. The loss of those ships sealed Hannibal’s fate, and in 203 B.C. he was ordered to return to North Africa.

When the Carthaginian envoys arrived and relayed the order to return, Hannibal was barely able to contain his rage. He gnashed his teeth and cried out that he had been betrayed, defeated by the aristocratic faction in Carthage, led by Hanno, not by the Romans he faced on the battlefield. He bemoaned that he would fail in this war for the same reasons his father had failed forty years before—lack of support from home. Several towns in Bruttium, seeing the writing on the wall, deserted Hannibal and tried to make their peace with Rome. In response, he dispatched the weakest of his soldiers, those he classified as “unfit for duty,” to garrison some of them, which he now held, more by force than loyalty.

“The Carthaginian Wars 265-146 BC: • Samnite heavy infantryman • Campanian cavalryman • Lucanian heavy infantryman”, Richard Hook

In preparation for his return to Africa, Hannibal ordered timber cut from the forests of Bruttium and transported to Crotone for use in building ships. The completed transports would be escorted on their voyage home by a few warships from Carthage that had eluded the Roman navy and made it to Crotone. Hannibal carried out his preparations with “bitterness and regret.” He assembled the elite of his army, some twenty thousand of his veterans, who by this point must have been mostly Italians from Bruttium and Lucania, and announced their departure for North Africa. Their response bordered on mutiny. What the ancient sources refer to as a large number refused the order and barricaded themselves in the temple of Juno Lacinia, where they sought sanctuary. Confident that Hannibal would never violate the sanctity of a holy place, they misjudged the man who for his entire adult life apparently had no fear of the gods. Hannibal had the temple surrounded and, according to one of the sources, thousands of rebellious soldiers slaughtered along with horses and pack animals.

The scope of this massacre has often been regarded by scholars as an exaggeration in the ancient sources that probably stems from the reported slaughter of three thousand horses that could not be taken on board the ships to Africa. There certainly may have been mutinous soldiers at that point in the war, and Hannibal may well have had them executed. But the Italian contingents in Hannibal’s army were his core, his veterans, and he needed them. By this time, few, if any, of the mercenaries who crossed the Alps with him could have been left. It would be the Italians, those who had fought with him in southern Italy and who were prepared to accompany him to North Africa, who would prove to be his most reliable soldiers in the next and final stage of this long and destructive war.