One of the bitter lessons that the British had learnt from the Dieppe raid in 1942 was that armoured support was essential for supporting the assaulting infantry. At Dieppe, half of the Churchill tanks that landed on the beach either lost tracks in the shingle or had difficulty crossing the sea wall to get off the beach and support the troops inland. Of the twenty-nine Churchills landed, only fifteen tanks were able to get onto the promenade before road blocks eventually halted their progress inland and forced them to return to the beach. A total of eighteen tanks were immobilised by gunfire that knocked their tracks off, and four more tanks got stuck in the chert shingle on the beach. The Germans could not believe the British would abandon their latest tanks on the beach to be examined at their leisure and presumed the Churchills were obsolete tanks that the British could afford to lose.

It was not an auspicious combat debut for the Churchill tanks, but their sacrifice helped identify many of the challenges of an opposed landing. The Operation Overlord planners moved to address some of these problems with the formation of the 79th Armoured Division a year before D-Day under Major-General Percy Hobart to develop and test the specialist armoured vehicles needed to overcome the obstacles expected to be encountered in future landings in France. The 79th Armoured Division also provided training for men to operate this equipment; the US Army had no equivalent.

A shortage of landing craft was influencing Allied planning (i.e. the delayed timing of Operation Overlord for the invasion of north-west France and Operation Anvil/Dragoon for the south of France landings) as there were not enough craft to make simultaneous landings. Given the shortage, the British were concerned that landing craft would be vulnerable on the run into the beach from shore defences. One devastating hit on a landing craft from a gun could eliminate four or five tanks in one stroke. This was despite the fact that at Dieppe no tank-carrying landing craft were lost on the actual run-in to the beach, although many were damaged and several sank after off-loading their tanks. The Royal Navy did, however, lose more than thirty landing craft of all types in the operation. One solution was to convert a number of landing craft to fire rockets for close support after the naval bombardment had ceased, but this only compounded the shortage of such craft. Another solution was to provide the tanks with flotation equipment so they could swim in under their own power, thus presenting smaller and more dispersed targets. On touchdown on the beach, the tanks would then be immediately available to support the infantry.

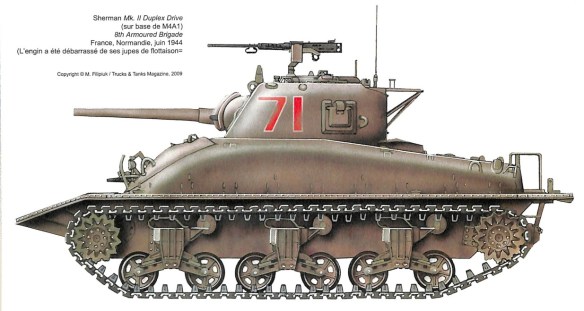

Work on a floating tank had already begun using a design originally conceived in 1941 by an American, Nicholas Straussler, and successfully used on Valentine and Tetrarch tanks. As these tanks were outdated and the British were standardising their armoured units around the Sherman M4 as their main cruiser tank, the design had to be altered to suit the Sherman. The realisation of the floating tank concept became one of Major-General Hobart’s projects.

A rubberised canvas screen fitted around the top of the tank hull was erected and held taut by a combination of metal struts and inflatable pillars filled with bottled compressed air. The canvas screen was raised by thirty-six pillars when compressed air was pumped into them via a pneumatic system, and thirteen metal struts fixed between the tank and the screen helped to keep it erect. The screen itself was attached to a boat-shaped metal framework welded to the tank’s upper hull. This system could be inflated in 15 minutes and could be quickly deflated when the tank reached a depth of 5ft or less. The tank floated according to Archimedes’ principle: with its additional canvas screen, it displaced more water than it weighed. The struts were fitted with a hydraulic quick-release mechanism to collapse the screen and allow the 75mm main gun to come into action when the tank arrived on the beach. If the screen was not properly lowered, the bow machine gun could not be used. Once the screen was deflated and ejected, the tank had the full use of its turret and could operate as a normal tank.

A modified Sherman tank was known as a DD tank, so named for its double, or ‘duplex drive’ systems that by means of a pair of propeller screws at the rear could propel the tank in water at a speed of up to 4½ knots as well as power it on land. The Americans inevitably nicknamed the DD tanks ‘Donald Ducks’.

The Sherman II (M4A1), as used by Americans at Omaha and Utah sector beaches, had a freeboard of 3ft in front and 2.5ft at the stern when unloaded. The slightly larger (by 5.5in) Sherman V (M4A4), as predominantly used by the British, had a freeboard of 4ft at the bow and 3ft at stern.

To launch from their landing craft, a tank drove on its tracks down the lowered modified ramp into the water and then engaged the Duplex Drive to operate the propellers. This meant a dangerous delay of a few seconds in which large waves could potentially push the tank back into the ramp or the landing craft could run down the tank if a wave caused it to suddenly surge forward. Once launched, the tanks could not get back on the landing craft. When the screen was erected, the driver’s vision hatch was blocked by it, so steering was by means of a periscope and a gyroscope, following the commander’s instructions. The driver steered the tank by means of a rod linkage that swivelled the propellers at the rear of the tank. The tank commander, as his view out of the turret was also blocked by the screen, helped steer the tank by using a simple detachable tiller linked to the steering mechanism while standing outside the tank on a plate welded to the back of the turret. The tank commander was very exposed in this position outside the tank, and as soon as enemy fire was received, he was forced to duck back into the turret while the driver continued to steer by means of his gyroscope. However, heavy seas made the gyroscope very unstable and difficult to read so at the most crucial time of the landing, when under fire and nearing the beach, the tank was virtually blind. The limited vision of the DD tanks, particularly under fire or in heavy seas, was recognised as a problem and during Operation Overlord a navigation boat was to be used to guide the DD tanks to a point where they could clearly see their intended landfall. Once launched, the raised canvas screen gave the DD tank in the water the superficial appearance of a smaller infantry assault craft, and it was hoped that this would disguise the tank during its approach to the shore.

Before being loaded on the landing craft, each tank had to be waterproofed by applying a putty-like compound to all joints, access plates, hatches and bolts before covering the putty itself with Bostik glue. The crews undertook extensive training in the form of practice launches, combined exercises and even practised escaping from a tank that had sunk. Scottish lochs and various lakes around England were used for these training exercises throughout the five months prior to Overlord. At Fritton Park, escape training was conducted with all tank crews wearing modified Davis Escape apparatus (as used in submarines), which provided a limited source of air. The crew took their place in a Sherman at the bottom of a concrete tower and water was rapidly pumped in, flooding the tank to a depth of 10ft. The crews then had to get out of the tank and swim to the surface, an operation particularly hazardous for the tank driver as he was the last of the crew to leave. A piece of equipment added to the DD tanks at the last minute for the Normandy invasion was an inflatable life raft of the type used by the RAF, a last-minute suggestion of Admiral Talbot, commander of the Sword sector Royal Navy forces in the assault.

The performance of the DD Shermans in rough weather was found to be poor in training exercises. The 13th/18th Royal Hussars lost two tanks in Operation Cupid in March 1944 when the weather turned bad during an exercise after the tanks had already been launched. In Operation Smash, April 1944, the 4th/7th Royal Dragoons lost six tanks when they were launched in a heavy swell and then conditions worsened; six men were drowned.

The DD tanks were demonstrated to General Eisenhower on 27 January 1944, and he was enthusiastic about their potential, directing the US forces to use them in their landings on the basis that any measures that might preserve landing craft were worth taking. The benefits of the deployment of the DD tanks in the first assault wave were thought to far outweigh any potential disadvantages. However, the deployment of DD tanks by both the British and American armies meant that there would not be enough DD conversion kits to go round, so a British expert was flown to the USA with the design drawings and the Firestone tyre company began the manufacture of kits with the intention of sending them to England. As the tanks had to be modified to install the screens, it was far more efficient for US manufacturers to install the kits in America, and the first 100 DD-equipped tanks arrived in Liverpool, England, six weeks later.6

The planned use of DD tanks was not greeted enthusiastically by all Americans, however. General Gerow, commander of V Corps and on the COSSAC (Chief of Staff to Supreme Allied Commander) planning staff, was not keen on the DD tanks as he had successfully landed tanks from landing craft directly onto beaches the previous year in the invasion of Sicily and thought the DD tanks impractical.

Ultimately, a shortage of DD kits meant that only two companies or squadrons of each battalion or regiment earmarked for D-Day would be equipped with DD tanks. The third company or squadron would be equipped with tanks with deep wading vents similar to those that had been used successfully in the Sicilian landings. Two trunks, or stacks, were fitted to extend the air intakes and exhausts of the tank, which permitted fully waterproofed tanks to drive off landing craft into water up to 6ft deep.

For the British, the shortage of DD tanks for Overlord was only overcome by taking over the training tanks of the 79th Armoured Division and by the transfer of 80 M4A1 DD tanks from the Americans in March 1944. The Americans’ initial order was for 350 DD tanks, and as only ninety-six were required for the operational use of the three tank battalions, with another ninety-six being for training, the Americans had plenty spare. First, however, they had to be shipped to England. As a result of this, many regiments did not receive their DD tanks until late May and there were few opportunities for training. Time at the firing ranges was even more limited as the DD tanks had to be transported by road which required the waterproofing to be redone before the tank could take to the water again. Travel was also restricted as the DD tanks were a secret weapon and any road movements risked them being seen by enemy agents. The Americans turned down the British offer of training instructors from the 79th Armoured Division for the DD tanks and practised at Gosport and Torcross for their D-Day landings under their own instructors.

Each British and Canadian regiment would have two squadrons of nineteen tanks in the assault. As each landing craft Mk III had space for five DD tanks in its hold, there was room for an extra tank to be used. On 17 May the RAC (Royal Armoured Corps) approved the use of forty tanks on D-Day, if there were sufficient tanks and crews available. Eighty-five DD tanks were finally allocated to each of the 2nd Canadian and 8th Armoured brigades and forty-two to the 27th Armoured Brigade, but some of these tanks were in the workshop for repair. The 13th/18th Royal Hussars in the 27th Armoured Brigade actually used forty tanks on D-Day, along with the Canadian Fort Garry Horse Regiment.

On 26 April 1944 General Hobart alerted the War Office and the ACIGS to a potential problem with the top rail of the canvas screen on Sherman M4A4 tanks. Owing to faulty manufacture it was very weak and liable to break, especially in rough weather. An investigation was undertaken and rectification work consisting of bolting a length of angle iron to the top rail was immediately carried out on 126 tanks, under the supervision of the contractor, Metro Cammell. This fault affected only the kits made in England installed on M4A4 tanks and was apparently not present in US-made kits, although these were made from British plans with the same specification. A British interim report in May stated that a steel tube with a higher tensile strength was now being used in production. The repairs were to be trialled by B wing of the 79th Armoured Division in rough weather before D-Day but these trials had to be cancelled ‒ owing to bad weather! There is no evidence that the Americans were informed of the potential problems before D-Day.

The training branch of the RAC believed the DD tanks could be classed as underwater craft and therefore the tank crews should be entitled to the same Special Duty Pay as submarine crews, but this was rejected by the War Office.

Hobart’s team developed a range of special-purpose vehicles for use in beach operations, the floating tank being only one of them. A Churchill tank fitted with a short-range mortar that fired a large explosive charge, known as a Petard, for destroying bunkers was developed. The Petard-firing tank was then used to build other special-purpose vehicles to cross obstacles, including a tank to carry a small box girder bridge that could be laid across trenches and a tank to carry a bundle of planks (fascine) that could be dropped into ditches and trenches to enable other vehicles to traverse them. Another version (Bobbin) carried a canvas carpet for placing over soft ground to prevent vehicles from getting bogged. As these tanks were issued to army engineers, they were called Armoured Vehicles for Royal Engineers, or AVREs. Once the AVRE tank had completed its task, it was then able to operate as a normal Petard-firing tank. Another useful vehicle developed by Hobart’s team was the Flail, also known as a Sherman Crab, which was a Sherman fitted with chains on a rotating drum at the front of the tank to beat the ground ahead of the tank and explode any mines in its path.

Two myths have persisted in the aftermath of the debacle on Omaha beach. The first is that the Americans refused to use the British specialised armour at all and the second is that the Omaha landings nearly failed because British AVREs were not used in the assault.

All of the specialised tanks were demonstrated to Eisenhower and FUSA generals at Tidworth early in 1944 and FUSA rejected them all except the DD tank. One of the reasons given was that the US forces were developing their own M4 versions of the British tanks and that the US Army did not want to add another type of tank, the Churchill, to their inventory. As 115 Churchill flamethrower tanks had already been ordered in February 1944, this was disingenuous. As the USA was developing its own mine-clearing tank, the T1E3, the Sherman Flail was also turned down. However, in November 1944 the Sherman Flail was adopted by all US forces in the ETO and the T1E3 was quickly phased out.

Therefore the first myth is just that, a myth. FUSA was prepared to use whatever vehicles it saw a need for and would employ British designs where necessary if there was no duplication with the US Army’s own developments. The refusal to adopt the British Flail tanks was shortsighted, as was the late decision to rely on M4 bulldozers, of which only four were available for each unit on D-Day. It has been argued that the shortage of LCTs prevented the Americans from using the British AVREs, which is not true: FUSA simply did not want them.

Regarding the second myth (that US landings at Omaha nearly failed because they did not use the specialised armour), a report of the 79th Armoured Division claims:

There is no doubt that the troops of the Division were of inestimable value on ‘D’ Day and thoroughly justified the time and material that had gone into their specialist training and equipment. … It was the overwhelming mass of armour in the leading waves of the assault, the specialist equipment coming as a complete surprise, that overwhelmed and dismayed the defending troops and contributed a large part to the combination of strategic and tactical surprise which resulted in the comparatively light casualties suffered by our troops on ‘D’ Day.

While the specialist AVREs had mixed success, the performance of the DD tanks in the weather conditions of D-Day was far from successful and the DD tanks could have been landed directly on the beaches without any significant losses of landing craft and tanks. The DD tanks at Omaha did not contribute their full mass to the assault as many sank before the assault even began.