EXPERIMENTS IN CAMOUFLAGE

The losses of Cambrai in 1917 didn’t just teach the British about the need for armour when flying low over the enemy – they highlighted the need for protection from enemies flying above too.

British fighters tasked with daytime missions had, up to that point, generally been painted in mixtures of iron oxide and lampblack which resulted in a sort of drab brown colour. This was used for doping (painting) specifications PC10 and PC12. Also used were battleship grey and clear varnish.

After Cambrai, the Central Flying School’s Experimental Flying Section at Orford Ness on the Suffolk coast was set the task of devising a doping scheme that would break up a trench fighter’s outline and make it harder to see.

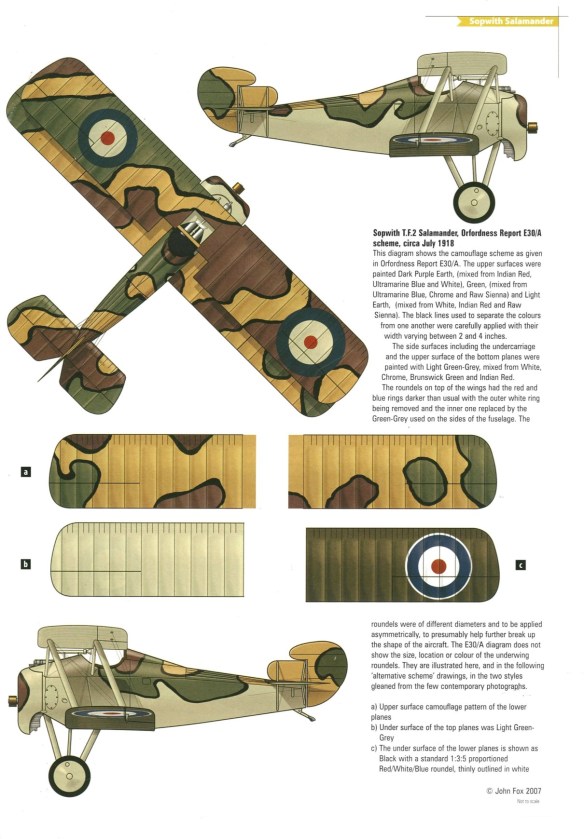

The Salamander was naturally an ideal guinea pig for this work and J5913, built by the Glendower Aircraft Company, was the subject of several test schemes. Patches of brown and green were painted on the upper wing and fuselage with black lines to separate them. The circular markings on the upper wing were made darker than usual and the white ring normally applied around the outside was painted in grey-green instead.

There were no markings on the fuselage or stripes on the tail and the lower wings were painted an earthy brown. The grey-green colour was also applied to the fuselage sides. On the aircraft’s underside, the cockades were made larger to prevent British troops on the ground opening fire on the trench fighter by mistake.

While it was too late in the war for these schemes to be applied to aircraft already fighting at the front, notes were taken and when Britain’s fighters were camouflaged in 1938 ahead of the Second World War, similar schemes were applied.

Lieutenant Colonel John Salmond’s tactical air force [Royal Air Force in the Field] in France would need a low-level fighter-bomber. This role was currently being carried out by standard fighters, but losses to ground fire had been heavy and there was a case for giving the pilots more protection. How much was a matter of debate as more armour meant less maneuverability and air combat capability. In January 1918, a specification was released for an armoured ground-attack fighter. Sopwith put forward two proposals: a modified Camel with 130 lbs of armour, the TF1 (Trench Fighter 1); and a more heavily armoured plane, the Sopwith Salamander TF2, based on the Snipe, with no less than 600 lbs of defensive armour. As the Snipe was not yet in production, the Camel-based TF1 would be available long before the TF2. Weir, for production reasons, and Trenchard, for tactical reasons, favoured the lighter and more maneuverable Camel TF1, while the Air Ministry Technical Department preferred the more heavily armoured Salamander. Within a month, Sopwith had a prototype of the lightly armoured Camel TF1 in the air. In March, two prototypes were flown to France for service trials and the pilots felt the light armour would be perfectly adequate. A couple of squadrons were to be equipped with the plane as quickly as possible for trials, although work on the more heavily armoured Salamander still continued. Neither these nor many other new designs would arrive in time to meet the German spring offensive.

Once Camels entered service in 1917 they were extensively used for ground attacks and a prototype armoured Sopwith Trench Fighter (T.F.1) version was built. However, the project was shelved in favour of the Sopwith T.F.2 Salamander, conceived from the first for a trench fighting role. It carried 650 lb of armour to protect the pilot and the fuel tanks, and after field trials in France production was begun in the summer of 1918 despite the ridicule voiced by diehards like Biggles.

- E. Johns writing from his own memory of 55 Squadron attitudes some fourteen years earlier:

‘That’s the trouble with this damn war; people are never satisfied. Let us stick to Camels and S.E.s and the Boche can have their D.VIIs – damn all this chopping and changing about. I’ve heard a rumour about a new kite called a Salamander that carries a sheet of armour plate. Why? I’ll tell you. Some brass-hat’s got hit in the pants and that’s the result. What with sheet iron, oxygen to blow your guts out and electrically heated clothing to set fire to your kidneys, this war is going to bits.’

However, as so often with new British aircraft, production was too slow and only a handful of Salamanders were delivered before the Armistice. The sole successful armoured aircraft of the war was the German Junkers J.I, a remarkable piece of design since the engine, tanks and pilot were protected by a one-piece ‘bathtub’ of steel that also doubled as the fuselage itself, monocoque-style. It was introduced in the late summer of 1917 and was well liked by its German crews since it offered them immunity from just about anything short of armour-piercing cannon shells. RFC pilots, meanwhile, had to content themselves with sitting on cast-iron stove lids, just as in World War II bomb-aimers lying prone in the nose of their aircraft used car hub caps, and in Vietnam low-flying helicopter pilots sat on their flak jackets rather than wearing them.

RISE OF THE SALAMANDER

Sopwith had put its proposal for the ground attack version of the Snipe into official hands on February 1, 1918, even before the TF. 1 was complete. This was updated on February 11 when the company gave revised details of the armour it intended to install on the aircraft – an 8mm thick plate at the front, an 11mm thick plate across the bottom, 6mm on the sides and a double wall behind the pilot of 4mm and 2.6mm thicknesses.

All of this armour combined weighed a hefty 605lb – the equivalent of carrying four additional average sized men in the aeroplane’s fuselage. As with the TF. 1 also being worked on, it was envisioned that the TF. 2 Snipe would have a pair of downwards firing Lewis guns with five 97-round drums of ammunition each. It would also have a single forwards firing Vickers with 300 rounds.

Unlike the TF. 1, six prototypes were ordered for the TF. 2 on March 20, 1918. By now the report from France was in on the TF. 1’s downwards firing Lewis guns and all six were ordered to have a pair of fixed forwards firing Vickers guns instead, with 1000 rounds between them.

The name Salamander was approved for the TF. 2 on April 9, 1918, and the first prototype, E5429, made its first flight on April 27. It looked very much like a Snipe – though the two types were already diverging from their common ancestry – for example on April 23, it was decided that the Salamander’s Vickers guns should be staggered to allow more room for their oversized ammunition boxes.

It was overoptimistically reported on April 24 that all future Salamanders would now be able to carry 1850 rounds of ammunition. They would also, as of May 8, be able to carry a rack of four 20lb bombs – though Sopwith had some difficulty in finding a way for the release mechanism’s control cables to pass through the pilot’s armour plating and into the cockpit.

The RAF was less than enthusiastic about the Salamander at this stage, feeling that Sopwith had gone overboard and provided too much protection for its pilots. Controller of Aircraft Production Brigadier General Robert Brooke-Popham wrote on April 19: This machine has about 500lb of armour but will probably be unsuitable owing to its poor view and the fact that it will not be very handy. I pointed out that all we had ever asked for was a lightly armoured single-seater machine and a heavily-armoured two-seater machine, and that the TF. 2 did not fulfil either of these two requirements. With regard to the distribution of the armour on the Camels, I pointed out that it had been agreed that up to 100lb of armour was permissible, and it was obvious that complete protection could not be afforded but that as much protection as possible should be afforded to a) pilot b) carburettors c) magnetos. Petrol tanks should be protected by being covered with rubber i. e. self-sealing tanks.”

The first prototype E5429 was flown to France for testing on May 9 and arrived with 3 Squadron on May 17. It then went to 65 Squadron on May 19 but was damaged beyond economic repair when it crashed while its pilot was trying to avoid a vehicle crossing the aerodrome to reach the scene of another crash. The 65 Squadron report on the Salamander stated: “The machine gets up a tremendous speed with the nose slightly down, and for this reason I do not think that it will ever be well suited for trench strafing owing to the fact that it will be impossible to dive anything approaching vertically as the speed obtained would be too great.” The Air Ministry ignored this report and ordered 500 Salamanders at the end of May. While the first Salamander prototype had been fitted with `soft’ steel armour plates, those of all subsequent aircraft had `hardened’ plates made by four firms – William Beardmore & Co of Glasgow, Thomas Firth & Sons and Sir Robert Hadfield & Co of Sheffield, and Vickers.

It proved very difficult to obtain steel plates that were of sufficient quality for use in an aircraft however. The hardening process tended to distort them, making them awkward if not impossible to fit.

Sopwith itself complained that an engine back plate supplied by Firths would not fit because it was too deformed. Firths said it simply couldn’t rectify this problem and knew of no viable solution to it. Worse, it seemed that apparently straight plates could still spontaneously distort even after the aircraft had been completed.

After the war, on January 6, 1919, it transpired that one aircraft, F6599, had shifted badly out of its proper internal alignment for no obvious reason.

It was flown in this distorted state by Captain Copeland to determine just how much of a problem this distortion might pose to an aircraft in service. He reported on June 17, 1919: “Taking off it was very difficult to get the tail up.

“When I did the machine went up and almost stalled and I had to push the stick half forward and throttle the engine back a little.

“I climbed to about 1500ft without turning, I then turned. The machine is flying right wing low. I tried the machine with varying throttles taking my hand off the joystick to see what would happen.

“She went up every time and stalled. I tried it with the engine off. It did the same thing. I then landed and taxiing up I had to put on full le? rudder and hard right aileron to make her go straight. This, though, may have been due to the length of the grass on the aerodrome, which is very long and almost dangerous.

“The throttle controls were very loose and vibrated closed as soon as they were left alone. The machine is not safe to fly as it is.”

JUST A LITTLE TOO LATE

Three months after the original Salamander prototype was wrecked in France, another example was tested at Brooklands. It was naturally found to be heavy on the controls but still capable of being looped and turned without too much trouble. With the engine on full revs it was deemed “easily manageable” when flying close to the ground, though visibility was poor.

Tests had shown that its metal plates, except those on the sides, would deflect a German armour piercing bullet fired directly at them from 150ft away. The weaker plates on the sides would stop a bullet at anything over a 15º angle.

Its Vickers guns had 750 rounds each and it could carry the same bomb load as a Camel – four 20 pounders or a single 112lb bomb. The pilot testing the Salamander concluded: “Practically the only way in which the machine could be brought down would be by explosive bullets in a main spar – two flying wires shot away – or a direct hit from anti-aircraft.”

Many still believed at this stage that the Salamander was simply an armoured Snipe but the truth was that the two types now had few parts in common. The only interchangeable parts were apparently the tail skid and rudder. The primary reason for this difference was the need to give the Salamander strengthened parts that could take the strain of its enormous weight.

This was underlined when a mistake on the production line led to Snipe centre sections being used instead of Salamander ones. At a glance, they no doubt looked the same but there was a big difference in strength. On December 28, the Technical Department wrote to the RAF to say: “I am directed to inform you that it has been ascertained that all Salamanders hitherto delivered by Messrs Sopwith have been provided, by an error on the part of the firm, with Snipe centre sections, which reduce the factor of safety to 3.1 in the case of the front spar and 2.8 in the case of the rear spar, instead of the required factors of 7 and 5 respectively.

“As the machine is clearly dangerously weak, it will be necessary to withdraw machines at once from service, and to have instructions issued that they are not to be flown until rectified. I have to request you for immediate information as to whether this rectification can be made by units, or whether the machines will have to be returned for this purpose to depots or to the makers.

“In the latter case, it may be possible to arrange for correct centre sections to be supplied for this purpose by the makers.”

The war was over before the Salamander saw service but it was still in production by 1919 and squadrons had begun re-equipping with it. Sopwith built at least 337 Salamanders, the Air Navigation Company built at least 100, the Glendower Aircraft Company built 50 and at least 10 were made by Palladium Autocars. A total of 1400 Salamanders had been on order at the time of the Armistice.

The first Salamander unit was to have been 157 Squadron but despite receiving 24 Salamanders by October 31, the war was over before it could be transferred over to France and it was disbanded. Another squadron, No. 96, was also allocated a number of Salamanders but it is doubtful whether it ever received them.

In 1919, the Salamanders already produced were retained by the RAF rather than being scrapped and a small number were used for testing camouflage schemes designed to make them less easily seen from above while flying at low altitude. A couple of examples were still flying at the Royal Aircraft Establishment for this purpose at the beginning of 1920 and the type was listed alongside the Snipe, Cuckoo and Ship’s Camel as being in service with the RAF in February, 1922.

A single Salamander, F6533, went to the US for testing that year and it survived until 1926.