The Siege of Fort William, 20 March – 3 April 1746

The attention of all parties now shifted to Fort William, as the last surviving strongpoint on the chain of the Great Glen. Cumberland looked on it as ‘the only fort in the Highlands that is of any consequence’, and claimed that he was ‘taking all possible measures for the security of it’. The elderly governor, Alexander Campbell, was described as ‘a careful good man’, but doubts rose as to his competence during the blockade, and on 15 March he was superseded by Captain Caroline Frederick Scott of Guise’s 6th. Scott was the son of a landed family of Bristo, just south of Edinburgh, and few other lines in Britain were associated so intimately with the reigning house. His diplomat father was already a friend of Elector George of Hanover before he claimed die throne in 1714, and Caroline himself owed his curious name (and possibly, in compensation, his ferocious ways) to his godmother Princess Caroline of Ansbach, who became the queen of George II.

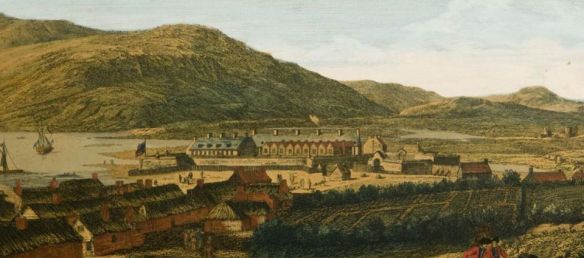

The garrison, as finally reinforced, was made up of two companies of Guise’s 6th, two other companies of regulars and a company of the Argyll Militia, about 400 men in all. The fort was more solidly built than Augustus, and its roughly triangular form was calculated to take advantage of the cover afforded by the head of Loch Linnhe, having a north-eastern side giving on to the salt marsh at the mouth of the River Nevis, a western side facing the loch, and three irregular bastions and a ravelin which looked inland to the east. The armament comprised six 12-pounder cannon, eight 6-pounders, seven smaller pieces, two 13-inch mortars and eight coehorns. There was plenty of ammunition, but there was no permanent supply of water within the fort.

On 25 February the garrison began to demolish the service town of Maryburgh so as to clear a field of fire, though nothing could be done to deny die besiegers the use of the outlying heights. Conversely, the location of the fort by the lochside not only gave the place immediate tactical strength, but made it accessible to craft that braved the Jacobite guns at the Corran Narrows. The defenders were supported by the sloop Baltimore and on 15 February she was joined by the bomb vessel Serpent.

Fort William had long been subject to intermittent blockade by bands of Camerons and Clan Donald, but the chiefs now called for a full-scale siege to take the place by force, and there were some valid reasons for doing so. In friendly hands it would remove an affront to Lochaber, deny the enemy their access to the south-western end of the Great Glen, and, as an offensive base for the Jacobites, enable them to make an inroad into Argyllshire and lay all before them waste – a prospect which induced Major General John Campbell of Mamore to fortify Inverary.

It is difficult to discover the thinking of the Duke of Cumberland. He expressed great concern for the safety of the fort, as we have seen, but at the same time he was glad that the depredations of the garrison had provoked the Jacobites into besieging the place, for that would ‘discourage the men [of the Jacobites] and add to their present distractions’.’” This interesting statement lends indirect support to the arguments of Prince Charles, who was ‘altogether against it… but the clans looked upon it to be so essential a thing to them, and for the good of the cause, that the Prince consented, though it was exposing himself and them, and even the cause to have the army so scattered’.”

The operation was entrusted to the same team which had taken Fort Augustus – Lieutenant Colonel Stapleton, the ‘French’ regulars and Lochiel’s and Keppoch’s clansmen. The logistic difficulties were more acute still, and the shortage of strong horses to draw the heavier guns from Inverness was aggravated by that bird of ill-omen, Mirabelle de Gordon, who, Stapleton was amazed to find, had reduced the number of beasts available from twenty-six to fifteen.

One of the precious 8-pounders was overturned on Wade’s road beside Loch Ness, and heavy rains in the middle of March swept away two sections of the further road alongside Loch Lochy at Letterfinlay. With uncharacteristic insouciance Colonel James Grant reported that only thirty-four 8- pounder shot were available out of the sixty which were supposed to have been brought from Perth, ‘but that will be quite enough, for a single 8-pounder will do the work – that’s all we need for a good start, and the Prince’s good luck will supply the rest’. Stapleton complained that he meanwhile had to wait uselessly outside Fort William with his ‘arms crossed’.

The landward blockade was loose enough to tempt the officers of the garrison to go on recreational walks beyond the ramparts. That was not a good idea, because the local people had suffered much from the garrison, and on 15 February a farmer of the village of Inverlochy shot down Lieutenant George MacFarlane as he was returning by the stepping stones over die River Nevis. In retaliation the governor sent an expedition that burnt down Inverlochy, as being ‘the common receptacle of the rebels’.

The Jacobites focused their seaward blockade down Loch Linnhe at the Corran Narrows, where they succeeded in capturing one of the Baltimore’s boats. Alexander Campbell determined to ‘destroy that nest of rebels’. Early in the morning of 4 March he embarked seventy-one of his men on six boats at Fort William, and over the course of five hours they made their way down the loch, surprised the sentries at the Narrows, and burnt the two ferry houses along with a small settlement a few hundred yards away on the western side. The Jacobites were reported to have had two men killed, ‘and many wounded as appeared by the quantities of blood left upon the roads’.

By chance the tender of the bomb vessel Terror had been waiting on the seaward side of the Narrows, having been detained on the way to Fort William by adverse wind and tide. The boat was carrying supplies, eighteen Argyll militiamen, and the young engineer Mr John Russell, who had been dispatched to give his expert opinion on the fort. Not knowing what was afoot, tile craft weighed anchor at 5 a. m. and fortuitously arrived at the narrows towards the end of the action. ‘After … everything was over, the master and I was standing upon the stern of the boat looking round us as some rascals from behind a boat fired most furiously upon us. We returned their fire with two swivels and a few muskets, but made off very fast for we could not see our enemy: we expected to be seized every hour. Everybody is in high spirits. French artillery will only inspire us with courage, and white cockades, will make us desirous after glory” Russell disembarked at Fort William on the same morning of 4 March, and discovered that the fortifications were ‘not in so good repair as I could have wished, the parapet being too low, and some of the wall very old, but the men of war defending one side entirely, I purpose to bring all the guns to the side which is liable to be attacked’.

After having been detained at Castle Stalker by contrary winds. Captain Caroline Scott and the bomb vessel Serpent were safely at Fort William on 15 March, and he drew up his rules for die conduct of the defence. Amongst other things, Scott laid down that the garrison must keep up a frequent harassing fire at night with light cannon, and

send out parties to listen. But take care not to fire while those parties were out. Also keep little patrols going all night on the outside of the walls for securing engineers or another sort of reconnoiterers … When their batteries are raised against us, to ply them well with all the guns we can bring to bear upon their battery from every part of our line, both great and small, and that by degrees, not all at once, but gradually to torment and hinder them from firing or loading their guns with a good direction.

There was no consistency of direction among the Jacobites. The sharp eye of Colonel James Grant had noted that the work was dominated from the south-east by a hill

whence one may discover everything that passes in the fort. Mr Grant proposed to begin by erecting a battery on this hill to annoy the garrison; and he had observed that one of the bastions projected so far as not to be defended by the fire of the rest, so he proposed to arrive at it by a trench and blow it up. But as he was reconnoitering, he received a violent contusion by a cannon ball, and Brigadier Stapleton having no other engineer, was obliged to send to Liverness for Monsieur Mirabelle, who began on a quite different plan, and succeeded no better at Fort William than he had done at Stirling.

The scheme of attack as actually carried out by Mirabelle de Gordon put the whole weight on the artillery, employing both cannon and 6-inch mortars. The Jacobites opened fire on 20 March and (although there is some uncertainty as to the actual sequence of the initial batteries) it is clear that the earlier sites – on the slopes of Sugar Loaf Hill and the slopes of Cow Hill – were too distant from the target. On the 23rd, however, a further battery was opened on the Cow Hill but closer to the target. The 6-inch bombs caused Captain Scott some concern for the overhead cover in the fort, but his gunners were hammering back effectively, especially against Cow Hill, and ‘we gather up all the splinters of the rebels’ shells thrown at us, and broke them small to serve as grape shot’.”

It was impossible for the besiegers to creep near the ramparts unobserved, for the nights were clear and moonlit and the only chance the Highlanders had to get to grips with the enemy was when watering parties left the fort. Whilst Scott succeeded in imposing his authority on this garrison, a spirit of division spread among the frustrated Jacobites. There were feuds between the Camerons and the Keppochs, between the ‘French’ troops and the Highlanders as a whole, and between the Prince’s Secretary, Murray of Broughton, and almost everybody else. ‘Lochiel and Keppoch are loud in their complaints against him, and the latter has threaten to beat him with a stick … these gentlemen accuse him of having sold off a great quantity of flour to the local people.

On 27 March the emphasis of the attack shifted from the mortars to the cannon, when the Jacobites unmasked a battery of four 6-pounder pieces on the ground above the Governor’s garden. On the night of the 28th the garrison saw a large fire disconcertingly close (at 300 yards) on the hillock of the Craigs Burial Ground, east of the fort, and the next morning the Jacobites opened an artillery attack from this side with red-hot shot, ‘which at first burnt some of the fellows’ fingers who went to lift the shot till they became more wary’. The aim was to make the cramped interior of the fort untenable, and further missiles included cold roundshot, grapeshot, old nails and (a Jacobite specialty) red-hot lengths of notched iron that were intended to lodge in timbers.

This time Scott was unable to hit back properly with his artillery, for the muzzles of die guns on the Craigs were difficult to see. Instead, upon detecting signs of commotion among the besiegers, he dispatched Captain George Foster with 150 men to assault the battery on the evening of 31 March. There was a muddled relief of the guard between the Camerons and the Keppoch which happened to leave the battery unprotected at the crucial time, and the sortie was able to spike two 6-inch mortars and a 6-pounder cannon, and bring back two more 6-inch mortars and three French 4-pounder cannon. The party then turned against the battery above the Governor’s garden, but this time without the advantage of surprise, and Scott had to send two successive reinforcements to get the troops out of trouble. They returned safely with the captured pieces, and the casualties in the whole affair were even, at eleven or twelve a side.

The siege had dragged on much longer than had been expected, and still to no purpose, and Prince Charles called on Lochiel and Keppoch to bring their men back to Inverness. The fire of the besiegers slackened on 1 and 2 April, and on the 3rd Scott found that the enemy had disappeared, leaving behind their equipment and all but their most easily transportable artillery. ‘I shall mount our prize guns (both those we took and the legacy the rebels left me when they marched off), on one corner of our walls that if any general officer comes here, they may be seen at one view.’

The Baltimore and the Terror, which had done so much to help the defence of Fort William, were units of a flotilla of sloops and surprisingly agile mortar vessels operating under the command of Captain Thomas Noel, from his 20-gun Greyhound. As well as supporting the garrisons, Noel had the wider remit of intercepting French sailings, and preventing or deterring the movement of Jacobite clansmen from the western capes and islands to the army of Prince Charles.

The first exercise in retaliatory power (much worse was to follow in the pacification) was entrusted to the naval captain Robert Duff of Logie, who was another of those Lowland Scots who were much embittered against the Jacobites. He took his bomb vessel Terror and the small supporting craft Anne to Mingary Castle to embark a force of Argyll Militia, and at 4 a. m. on 10 March he landed the troops and fifty-six of his armed sailors on the Morvern shore of the Sound of MuJl. By 6 p. m. the expedition had devastated 14 miles of coast from Drimmin to Loch Aline. The people had been able to escape with some of their effects, but nearly 400 of the houses of the Camerons and MacLeans were destroyed, along with barns, stores of grain, and cattle and horses. Curiously enough these folk were tenants of the Duke of Argyll, whose assets were thereby diminished. On 27 March a further expedition ascended Loch Sunart, and meted out the same treatment along the northern shore of the Morvern peninsula.

Reports on the Siege of Fort William from Scots Magazine March & April, 1746