These forts had been put in place by Field Marshal George Wade in the wake of the earlier Jacobite rebellion in 1715. As part of his pacification policy for the north of Scotland, Wade was responsible for the construction of defensive points at Fort George, Fort Augustus and Fort William, the aim being to control the important line of communication through Loch Ness and Loch Lochy, the route of the later Caledonian Canal.

The Hanoverian government ordered their commander-in-chief in Scotland, Lieutenant-General Sir John Cope, to make preparations for the defence of the Highlands, as that remote land mass would be the most likely focus for the raising of a revolt in support of the Stuart cause.

Reacting to the government’s orders, Cope ordered three companies of Guise’s Regiment to march to Fort William, the southernmost strongpoint, while an additional three companies moved to Fort Augustus and two others deployed to Fort George outside Inverness. At the same time single companies were sent to smaller garrisons at Bernera and at Ruthven near Kingussie. There was also a small presence at Castle Duart on the island of Mull. Each company should have been about seventy strong, but detachments had had to be withdrawn to furnish working parties on the roads, so the garrisons in place were inadequate to mount a serious defence to a determined attacking force. The challenge was not long in coming.

The first news of Charles’s landing had arrived in London, where the initial reaction was one of muted indifference. The only member of the Cabinet alert to the threat was the Duke of Newcastle, Pelham’s brother and foreign secretary, who wrote to the Duke of Cumberland, commander-in-chief of the government forces in Flanders, warning him that he might have to send back some of his infantry regiments. A warning was also sent to the Earl of Stair, who commanded the army in England, but the elderly field marshal believed that the 6000 soldiers at his disposal were ample to meet the challenge. At the same time Cope was proceeding with his intention of strengthening the lines of communication in the Highlands and had ordered two companies of the Royals to make their way without delay from Fort William to Fort Augustus to reinforce the garrison. It was a distance of no more than thirty miles but the order was fraught with difficulty: the barely trained infantrymen were unused to the mountainous terrain, having served only at the depot in Perth prior to embarking for service in Flanders.

On approaching Wade’s High Bridge (close to present-day Spean Bridge) on 16 August, the Royals, under the command of Captain Scott, were ambushed by a group of Highlanders loyal to Donald Macdonnell of Keppoch. Unnerved by the sudden and unexpected firing, Scott’s men retreated back down the track, and after a brief skirmish they were forced to surrender to Keppoch. Scott and three other officers, together with eighty NCOs and infantrymen, were taken prisoner and marched off to Achnacarry, where Charles showed leniency by offering parole on condition that they did not serve against him again. The same treatment was meted out to Captain John Swettenham, a military engineer sent by Wentworth to gather intelligence who had also fallen into Jacobite hands.

Both incidents were good for the morale of Keppoch’s men and they undoubtedly influenced Lochiel in his decision to support the uprising. From a military point of view the skirmish and Swettenham’s capture would also influence the following course of events.

The key to the tactical situation lay in the government forts, which were suddenly open to attack. Wentworth recognised the danger and told his cousin Thomas Watson-Wentworth, Lord Malton and Lord Lieutenant of the West Riding, that ‘the Pretender with 3,000 highlanders is six miles off’. Cope also saw what was happening and realised that if the forts fell it would hamper his own plans to march into the Highlands to destroy the rebellion before it gathered momentum. On 19 August he rejoined the government forces in Stirling, before heading north to Dalwhinnie by way of Crieff and Dalnacardoch with a small force of 1500 infantrymen representing Murray’s, Lascelles’ and Lee’s regiments, most of them under strength and all untested. From there he proposed marching towards Fort Augustus, a route that would take him over the wilds of the Corrieyairack Pass, the only passable crossing place in the western Monadhliath mountain range – Wade had recognised its importance when he built his twenty-eight miles of zig-zag military road in 1731. Corrieyairack was the strategic equivalent of Afghanistan’s Khyber Pass: the commander who held this position was in possession of the only viable route for a rapid descent from the West Highlands into the Lowlands.

Before leaving Edinburgh, Cope had discussed his tactics with a number of leading grandees, including Lord President Duncan Forbes of Culloden, and throughout his march he was in constant correspondence with the Marquess of Tweeddale, the ineffectual Secretary of State for Scotland, who was inclined to minimise the threat posed by the Jacobites. With so many political masters having to be placated, Cope was in a parlous position, but once he had committed his force to move into the Highlands his military thinking was sound enough. Recognising that in such terrain artillery and cavalry would not be helpful, he decided to leave behind his field guns and two regiments of Irish dragoons and to move as quickly as possible with his infantry. According to the testimony of one of his officers, Lieutenant-Colonel Charles Whitefoord, Cope ‘kept the Highlanders always advanced, extended to the left and right, with trusted officers who were to make signals, in case of the enemy lurking in the hills’.14 On 26 August Cope reached the small village of Dalwhinnie, which justified its Gaelic name Dail Chuinnidh (‘meeting place’), for it was here that he had to decide whether or not to continue towards the Corrieyairack Pass or to veer north-east towards Inverness. It was here, too, that he received the intelligence that a superior force of Jacobites had already beaten him to the pass.

What is more, the information was confirmed by Captain John Swettenham, who although on parole passed on the intelligence to Cope as his superior officer. Earlier Swettenham had witnessed one of the high points of the uprising (and an iconic moment in Jacobite historiography) when he was present at the gathering of Prince Charles’s supporters at the head of Glenfinnan. Having given instructions to muster at the meeting point of the glens of the Shlatach, the Finnan and the Callop, Charles and his retinue arrived shortly after midday. To begin with he only had a small bodyguard of some four hundred Macdonalds, a handful of Macgregors and Glenbucket’s Gordons, but as the afternoon dragged on and tensions no doubt grew, the sound of bagpipes was heard from the east, heralding the arrival of eight hundred Camerons. Lochiel had been true to his word and in so doing produced a wonderfully dramatic scene which Charles was able to milk to the full. The Jacobite standard was unfurled, James Stuart was proclaimed king and the blessing was provided by Hugh Macdonald, Bishop of the Highlands. Several onlookers remarked that Prince Charles had never looked happier than he did at that moment. He had 1200 men under his command and the rebellion was now a reality.

#

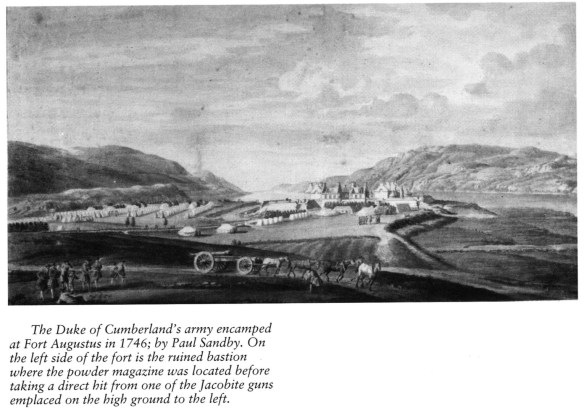

By the beginning of March 1746, having established himself at Inverness and its environs, the Prince Charles Stuart’s key immediate objectives were to reduce Fort William and Fort Augustus, to disperse Lord Loudoun’s army and to keep possession of the coast towards Aberdeen for supplies. Lord Loudoun had retreated, with Lord President Forbes and a majority of his men (excepting the garrison at Fort George), to Dornoch, taking all the available boats with him (as Captain MacLeod had stated) and therefore making pursuit extremely difficult. Once at Dornoch he was able to successfully defend himself against an attack by Lord George. He and his party eventually withdrew to Skye. At the same time Lieutenant General Walter Stapleton of Berwick’s regiment, accompanied by the Royal Ecossais, three Irish picquets and, crucially, the chief engineer Colonel James Grant of Lally’s (who had been mysteriously absent at Stirling) advanced to Fort Augustus, then under the governorship of Major Hu Wentworth. The siege began on 3 March. After some well-aimed shelling, which set fire to the powder magazine and eventually blew a breach in the outer wall, Major Wentworth surrendered on the 5th.

After the successful siege of Fort Augustus, Lieutenant General Stapleton had left Lord Lewis Gordon in command and marched on to Fort William accompanied by the Camerons and MacDonalds of Keppoch, who ‘were particularly interested in the success of it, as Fort William commands their country; and during the Prince’s expedition to England, the garrison made frequent sallies, burnt their houses, and carried off their cattle’. The garrison was commanded by Captain Caroline Scott. Colonel Grant began raising the batteries on 20 March and proceeded to pound the fort for over a week, during which he was injured. The comte de Mirabel took over and ‘succeeded no better . . . than he had done at Stirling’. On 31 March two parties sallied out from the fort to attack the batteries and succeeded in spiking the guns in one battery and taking prisoners from both. A few days later the siege was abandoned and the Jacobite troops retired back to Inverness. At about the same time, Lord George and his men were also ordered to return to Inverness, allowing Major General Crawford the opportunity to relieve the starving garrison at Blair Castle.

The Siege of Port Augustus, 3-5 March 1746

The forts Augustus and William had been thorns in the sides of the western clans, and when their chiefs saw how easily Fort George had been taken they clamoured for the siege of those two offending objects. Prince Charles accordingly released the Irish picquets, Royal Ecossais and more than 1,500 of the clansmen of Lochiel, Lochgarry and Keppoch, who descended on Fort Augustus at the end of February:

God knows what pains we had to send them the artillery, ammunition, meal and even forage, for there was not a scrap to be had in that part of the country; die roads were frozen, the horses reduced to nothing, and not a carter who knew how to drive or guide them. Our small pieces of cannon could be of no great use, only to fire on the barracks. All that we had to depend upon were two pieces of eight that were found in the Casde of Inverness [Fort George], and three or four small mortars that were taken at the battle of Falkirk … there were but sea carriages for our piece of eight pounds. The French ambassador [d’Eguilies] undertook to get carriages made, and so he did, but only one of these pieces arrived, the other carriage broke, and the cannon was left on the road.’

It was fortunate for the Jacobites that Fort Augustus had been designed ‘more … for ornament than strength’, as a demonstration of Hanoverian presence in the Highlands. It was badly sited, the curtain walls were feeble, and vital installations were installed in full view in conical towers on top of the four bastions. The garrison was more powerful than that of Fort George, being made up of three companies of Guise’s 6th, but the governor, Major Hu Wentworth, placed one of them in an isolated position in the old barracks of Kiliwhimen on the higher ground to the south.

Lieutenant Colonel Walter Stapleton, as commander of the ‘French’ troops, evicted the redcoats from the barracks by a straightforward assault, and Colonel James Grant was able to open his first trenches against the fort proper on 3 March. The Jacobite cannon were of little use against even these unimpressive ramparts but on 5 March a bomb from one of the coehorn mortars broke through the roof of the magazine. The resulting explosion breached the bastion beneath, which laid the fort wide open to an assault. The governor surrendered without more ado, which was only sensible, though he was later court-martialled and dismissed from the service.