The wind and spray of the Western Mediterranean pelted Jack Taylor as he piloted the 150-ton Samothrace across the turbulent blue-green water. Controlled by the Axis, the Aegean Sea was swarming with roving patrols of enemy ships and planes, which provided a formidable challenge to the MU’s first mission. A master sailor, Taylor felt at home at the helm of the 90-foot sloop. Years of experience on solo cruises across the Pacific, yacht races in the Caribbean, and a narrow escape from being buried alive in a gold mine in the Yukon had given Jack Taylor skills and mental toughness few men possessed.

In September 1943, Taylor set off on one of the most dangerous voyages in the eastern Mediterranean. His orders were to deliver critical supplies to the Greek island of Samos, located less than a mile off the coast of Turkey. Samos was the birthplace of several ancient Greeks, including Pythagoras, Epicurus, and the astronomer Aristarchus, but at this time it was part of a tiny pocket of Allied occupied islands surrounded by Axis garrisons. Taking the helm of the Samothrace—now serving as a cargo vessel—Taylor departed Cairo with two tons of food, TNT, Tommy guns, ammunition, and camp equipment. The expert sailor adroitly navigated the ostentatious schooner and dropped anchor at the OSS’s caïque base at Pissouri, Cyprus, code-named “Cincinnati.” The OSS had several of these hidden coves, all code-named for prominent American cities, and they used them to refuel, make repairs, and even hide agents. As the war dragged on, the OSS established nearly a dozen of such covert marine bases across the Aegean.

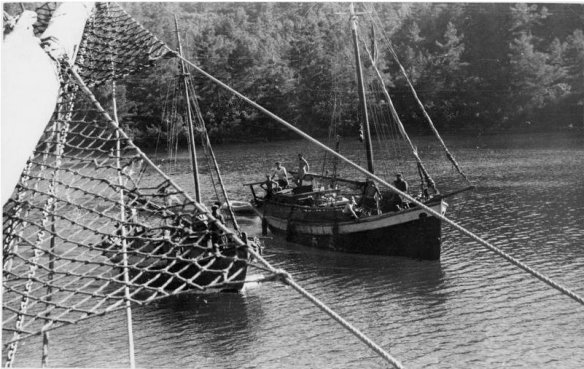

Jack and his team unloaded the supplies and ammunition onto the Irene, a fifteen-ton caïque awaiting their arrival. They saved space for fifteen hundred pounds of “urgently needed medical supplies for Samos arriving by air from Cairo.” Little more than a rotting tub, the Irene had a breakneck top speed of only two knots in calm water. Like many of the boats, it carried sails as a secondary means of propulsion. But with “Samos being dead to windward, sails could not assist. It was an impossible situation,” Taylor reported. In desperation, Taylor sailed to another port in Cyprus known as Famagusta to “grab any fast caïque and talk about it later.” Though the Greek government was holding two “very suitable caïques for size and speed” for no apparent reason, the local officials refused to allow Taylor to put them to “good use.”

It was then that Taylor, in his own words, “blew a fuse.” He enlisted the help of OSS operative Captain John Franklin “Pete” Daniel III to make an urgent plea to the Greeks. Captain Daniel, code-named “Duck,” was the Cyprus chief of the Greek Desk for Secret Intelligence and spoke the language fluently. As a former professor of archaeology at the University of Pennsylvania who had conducted extensive digs in areas around the Mediterranean, Duck was extremely knowledgeable about the culture and government. Jack asked Daniel to explain that the “U.S. was not interested politically or economically in post-war Greece; that [the U.S.] wanted nothing in return for helping them; that the money and resources expended were for the sole purpose of aiding their people; that [the OSS] was not begging for the loan of a caïque to deliver humanitarian supplies which [they had] every right to do but wanted only to charter the transportation from them, and it seemed that [the Greek officials] were very unappreciative.” Their impassioned entreaties ultimately persuaded the Greeks to lease the Americans three capable boats: the Mary B., the Kleni, and the Angelike.

The OSS crew transported the much-needed supplies and medicine onto the new boats. Taylor, along with two secret intelligence agents and their equipment, sailed aboard the Mary B. On October 1, 1943, the three caïques set out at dawn. The occasional British patrol planes and low-flying German surveillance planes passed over the small flotilla as they headed to Samos.

En route, the caïques docked briefly at another of the OSS’s forward operating bases, a secret harbor code-named “Miami.” Then, on October 3, at 8:15 a.m., Taylor got his first taste of the grim realities of war. After the caïques left the relative safety of their base, eight German Junker JU-88s “dive-bombed and strafed a destroyer close under the south coast of Kos. Plenty of ack-ack [anti-aircraft fire] and one shot down, crashing and burning on the hillside.” The German dive bombers sank the British destroyer. According to Taylor, “One of the Junkers came out of his dive in our direction and gave us a long burst with cannon and machine guns. The Greek crew, with the exception of the helmsman, were so busy diving for the hold . . . that I was not able to accompany them. . . . One bomb burst fifty yards to the starboard.” With the crew badly shaken by the attack, Taylor then changed course, and the small fleet hugged the Turkish coast to avoid German planes. Taylor then witnessed another battle on the island of Kos around 12:30 p.m.: “Nine Junkers circling easily just above the ack-ack. Absolutely no fighter defense. Several warships, the largest probably a light cruiser . . . were counted through the glasses. Float planes directed the fire. Airfield and ammunition dump were bombed, sending up a huge smoke and debris column.”

At 7 p.m., Taylor and his crew departed from the coast of Samos for Kos. Taylor then reduced speed to ensure that the island hadn’t fallen to the Germans. Over the next several months the islands around Samos would be the scenes of some of the most intense fighting in the Aegean. The strategic location of the islands made them a valuable prize to both the Allied and Axis forces. Later, a daring German airborne and amphibious attack would assault Leros, resulting in the capture of thousands of Allied prisoners of war. Fortunately, at 7 a.m. on October 4, when the Mary B. and the other craft entered Vathy Harbor at Samos, Taylor saw the British and Greek flags flying, signifying that the port remained in Allied hands.

While at Samos, Allied authorities informed Taylor that the Germans had captured Kos and heavily bombed Leros. With the potential for German invasion weighing on his mind, Taylor quickly delivered the cargo, including the much-needed emergency food and medical supplies, to the archbishop of Samos, who was also an agent for MI-6, Britain’s foreign intelligence service. The bishop informed Taylor that many of the people, including guerrillas, desperately needed items that could only be secretly procured on the Turkish black market, including insulin. Taylor agreed to undertake the mission. From Samos, Taylor and his small flotilla set sail for Turkey.

Desperate to get to the island of Leros where his battalion was fighting, Colonel May, a British doctor temporarily detached from his duty on Leros, approached the leader of the Greek guerrillas on Samos. Although he pleaded his case valiantly, the command major gave him little hope. Everyone knew the Germans were attacking Leros, and most believed the island would soon fall—if it hadn’t already. The guerrilla leader knew of only one man who might be willing to risk his life to make that journey: “If that crazy Yank doesn’t come back, I’m sure I won’t be able to get anyone else to take you,” the command major told May.

The “crazy Yank” was Taylor, of course, and he was already on his way back to Samos. The streetwise lieutenant and the shrewd “Duck” had savvily handled the negotiations—for which no spy training could possibly have prepared them—to procure the insulin and other supplies for the archbishop from the Turkish black market. However, getting out of Turkey proved its own ordeal. Taylor and his companions endured “three hours of haggling, bribing, fines, delays, inspections, bullshit, and just plain uncooperativeness” before obtaining authorization to leave the port. Fortunately for them, the journey back to Samos on the Mary B. was largely uneventful.

However, their next mission proved even more dangerous than the first. On Samos the Mary B. picked up Colonel May and two other doctors who were determined to travel to the island of Leros to rejoin their British units and support the defense of the island. The only problem was that the BBC had reported that Leros had already fallen to the Germans. Taylor “checked with the signals office, and they said it was still in British hands.” So the intrepid American began plotting a daring nighttime mission to drop the doctors off at daybreak—hopefully before the serious fighting resumed. May confided in Taylor that “he had thought his last chance [of getting to Leros] was gone.”

Before departure, Taylor once again radioed Leros, and although there was some contact, they were not able to communicate clearly. Taylor recalled, “The operator assured me the signal I heard was his operator in Leros and not a German operating his set. That was all the confirmation I could get” that the island had not yet fallen.

The “Crazy Yank” was willing to risk his life to transport the doctors, but the Greek caïque crew demurred. Taylor remembered, “We prepared to shove off, but it seems the Greek crew had heard the BBC report about Leros too and weren’t eager to go into Nazi-land. I told them we were going and if they didn’t want to come that they could stay and I would take the boat. They decided to go.” Of course, Taylor had some misgivings of his own. Of Colonel May he wrote, “It seemed all wrong to return such a good man and excellent Doctor to be captured so soon. That was the way he wanted it however, as it was his battalion and he wanted to be with them at the end. He reminded me it was an Irish Battalion and not to sell them short.”

As the Mary B. got underway in the strait between Samos and Turkey they came under fire in the darkness from the Turkish side. So they sailed closer to Samos, but then took rifle fire from that island as well. They arrived at Leros at 5:30 a.m. on October 7, 1943, just as the sky was beginning to lighten. Taylor recalled, “Departing, we were picked up by a searchlight and followed out of the bay until overtaken by a British [motor launch] and an Italian MAS (Torpedo Armed Motor Boat). The British checked us for a few seconds (we were flying the American flag) satisfied themselves and left, but the [Italian boat] insisted on stopping us with all guns trained. Not to be outdone, [one of the OSS agents on the Mary B.] picked up his Tommy gun and with barrel pointed at the skipper of the MAS, continued the discussion, which was not only useless and annoying but wasted valuable minutes when we should have been clearing the island.” At this point in the war, the Italians, whose government had recently left the Axis and sided with the Allies, were unsure who was friend or foe. Eventually the Italian crew let the OSS boat pass, and the flotilla departed Leros, making “more knots than Mary B. could comfortably handle with motor and sail.”

Taylor’s group left the island just in time. By 7:00 a.m. they could hear the first wave of Nazi war planes arriving on Leros. “Bomb burst and ack-ack were heard a few minutes later. Several groups followed, and detonations could be heard after we reached the Turkish coast.”

Winston Churchill continued to push for operations in the Aegean with an eye on a postwar world; however, the Allies lacked sufficient resources to conduct operations in the area. As a result, the British operations failed. Ultimately the Germans boldly counterattacked with a combined airborne and amphibious assault. They crushed the British garrison on Leros, which had a critical airfield, and seized the island of Kos. Soon they also encircled Samos and cut it off. In an unheralded operation, OSS caïques successfully evacuated hundreds of Greek and British personnel from the island.

Taylor’s experience on the missions to Samos and Leros highlighted the glaring need for high-speed motorboats. The caïques were mechanically unreliable and extremely costly to operate. The OSS took a number of stopgap measures to compensate for the boats’ problems, including swapping out the marine engines for tank and aircraft engines that the service somehow obtained. For months Taylor hounded OSS and Allied headquarters in the area to provide his fledgling Maritime Unit with fast motorboats.

Despite the lack of high-speed craft, Taylor accomplished a great deal in the few months he was in Egypt. Additional MU personnel hadn’t left the United States by October 8, so Taylor had to rely entirely on himself. Of his accomplishments in the region the chief of the Maritime Unit in Washington noted, “Lieutenant Taylor has been successful in establishing water transportation out of Alexandria to various island contacts, and his service is being enthusiastically received by all parties in the Middle East. Lieutenant Taylor is the caliber of a man who can do a big job in his field; in spite of all handicaps he has proven his worth to Maritime.”

Always forward thinking and pioneering, Taylor realized the fast craft he was requesting suited a range of missions, including those of the underwater variety that Taylor had spent so much time planning for in the States. He would later write, “Provisionally tried underwater swimming apparatus now includes underwater breathing apparatus and mask; luminous and waterproof watches, depth gauges, and compasses; protective underwater suit; auxiliary swimming devices; and limpets and charges. With this equipment and proper training, operatives could make a simple and almost perfectly secure underwater approach to a maritime target and effect a subsequent getaway. An underwater operative, for example, could place a limpet against the hull of an enemy munitions ship in a crowded harbor with good chances of destruction.”

Taylor also saw the opportunity to open up a new dimension of warfare, one that would become a hallmark of the U.S. Navy SEALs: parachute insertion. Taylor was one of the first OSS officers to document this groundbreaking method of delivering underwater commandos to the target, stating, “Underwater operatives and equipment might be landed by parachute to attack targets in inland waterways, such as hydro-electric dams on a lake or important locks in canals. Such an approach offers a unique technique in the penetration of enemy defenses.” Several months later Taylor’s innovative ideas were incorporated into the Maritime Unit training manual, which included an exercise to destroy a canal by parachuting underwater swimmers into the target, where they would don rebreathers and plant limpet mines along the enemy-held waterway.

The US Coast Guard and OSS Maritime Operations During World War II