Battle of Northampton

The Yorkist lords disappeared into the night, leaving their men and their banners at the mercy of their enemies. Whether by accident or design, they broke into two groups. York was accompanied by his second son Edmund – they immediately fled by sea to Ireland – but Edward joined the Nevilles. Edward’s party acquired a ship with the help of Lady Dinham, and it appears they may also have tried to reach Ireland. However:

when they had gone to sea, my Lord of Warwick asked the captain and the others whether they knew the way westward, and they answered they did not, they did not know these waters for they had never been there. The whole noble company then became fearful, but the Earl of Warwick, seeing his father and all the others were afraid, said to comfort them that if it pleased God and St George, he would lead them to a safe haven. And indeed, he took off his pourpoint [tunic], went over to the rudder and had the sails hoisted. The wind took them to Guernsey, where they waited for the wind, until by the grace of God they reached Calais.

The exiles were greeted by Lord Fauconberg: Warwick had left Calais in his care. Yorkist control of Calais, where Edward and the Nevilles arrived on 2 November, would prove crucial. Warwick’s prowess at sea would ensure the Yorkists possessed a secure base from which they could plot their return.

Back in England, a Parliament was held at Coventry: the so-called ‘Parliament of Devils’. The Yorkist leaders, including Edward, were declared traitors. Execution was not possible but the Yorkists were attainted, meaning their blood was deemed corrupt. Consequently, their descendants would not be permitted to inherit their lands and titles. The Yorkist lords were now legally ‘dead’, although the Lancastrian government continued to pursue them. Steps were also taken to deny the Yorkists a refuge: the young Duke of Somerset, supported by Andrew Trollope, was charged with the task of bringing Calais to heel. As we have seen, Somerset was a determined and aggressive man who passionately desired to avenge his father. He also possessed great charisma, and knew how to win and keep men’s loyalty. Somerset would prove a formidable adversary. Fortunately for the Yorkist lords, however, by the time Somerset was able to put to sea they were already safely ensconced at Calais. When Somerset approached Calais he was greeted by artillery fire from the Rysbank tower. Yet, refusing to admit defeat, Somerset moved down the coast and put ashore at Guines. He promised to pay the garrison their long overdue wages and was admitted to the fortress.

From his new base at Guines, Somerset did his best to harass the Yorkist garrison at Calais – ‘full manly he made sorties’, according to ‘Gregory’ – but without further support his mission could not succeed. Some of his supplies and men had already fallen into the Yorkists’ hands, weakening his position considerably. In December a fleet was assembled at Sandwich to go to Somerset’s aid. Lord Rivers and Sir Gervase Clifton were in command. But there was much sympathy for Warwick within the coastal towns and he was kept well informed of the Lancastrian plans. On 15 January 1460, in the early hours of the morning, a Yorkist fleet descended on the port. Lord Rivers, his wife and son were all taken captive. More importantly, Warwick’s men captured most of the Lancastrian fleet. Edward did not take any part in this daring exploit, but the surviving sources do suggest a growing prominence. William Paston recorded that Lord Rivers and his son Anthony were brought to Calais by the light of ‘eight score torches’. Then, according to Paston, Edward joined the other Yorkist lords in ‘rating’ [berating] the Woodvilles for their perceived pretensions. Perhaps this episode does not reflect especially well on Edward – and, as we shall see, there is a certain irony given the events that were to come! – but evidently ‘my Lord of March’ was now considered a person of substance whose activities were worth reporting.

By March 1460 the Yorkists were growing in confidence. It must have seemed clear that the Lancastrian government did not possess the necessary resources, or even the will, to displace them. Indeed, at this time Warwick felt secure enough to sail to Ireland, in order to consult the Duke of York, by now well established at Dublin. At Guines, however, the Duke of Somerset experienced immense frustration. A further Lancastrian expedition under the new Lord Audley was driven ashore by bad weather near Calais and Audley taken captive. Somerset’s position was now precarious, but he remained a tenacious opponent. Although Somerset was almost crippled by lack of funds and supplies, Warwick’s absence from Calais offered Somerset a glimmer of hope. On 23 April, St George’s Day, Lancastrian forces attacked Newnham Bridge, the gateway to Calais itself. The date is significant – doubtless Somerset wished to inspire his men by appealing to England’s patron saint – and this was a determined assault. But the Lancastrians were repulsed with heavy loss. Unfortunately, the details of this engagement are obscure, but is it possible that Edward was involved in the fighting? Assuming that Somerset attacked in strength, the Yorkist lords still at Calais would surely have gone out to meet him. Perhaps it was here that Edward first drew blood from an enemy. Shortly afterwards Warwick returned to Calais, despite the attentions of a fleet under the Duke of Exeter, who declined to engage. Warwick brought news of his talks with York, and the result had been profound. Edward was soon to be released from exile at Calais: the Yorkist lords would return to England.

In hard fighting, Lord Fauconberg and Sir John Wenlock won a bridgehead at Sandwich. On 26 June, Edward and Warwick took ship at Calais; with them were Salisbury, Lord Audley (who had defected to the Yorkists) and 1,500 soldiers. The Yorkists had also gained a useful ally in the person of Francesco Coppini, Bishop of Terni. Coppini had been sent by the Pope to preach a crusade in England, but he had now espoused the Yorkist cause. The weather was kind and the Yorkists ‘arrived graciously at Sandwich’. Propaganda had been disseminated in advance, which meant that a large number of Kentishmen rapidly answered their call to arms. At Canterbury, the three ‘captains’ who had been ordered to hold the city – John Fogge, John Scott and Robert Horne – decided instead to join the Yorkists. The Yorkist army reached London on 2 July. After some debate they were greeted by the mayor and the Archbishop of Canterbury, although the City Fathers tactfully suggested to the Yorkist earls that their stay in London should be brief. Doubtless they were worried about the prospect of conflict in London itself, because there was still a Lancastrian garrison in the Tower, under the command of the veteran Lord Scales. However, it is also likely that the Yorkist leaders wished to confront King Henry as soon as possible, before he had time to gather substantial forces. They were themselves desperately short of money and supplies, but in two days of whirlwind activity the Yorkist earls raised loans from within the city and organised everything necessary for the campaign to come, including horses and baggage. By 4 July the Yorkist army was ready to march and their vanguard led the way. A force under the Earl of Salisbury was detailed to keep watch on the activities of the Lancastrian garrison in the Tower, but the rest of the army followed the day after.

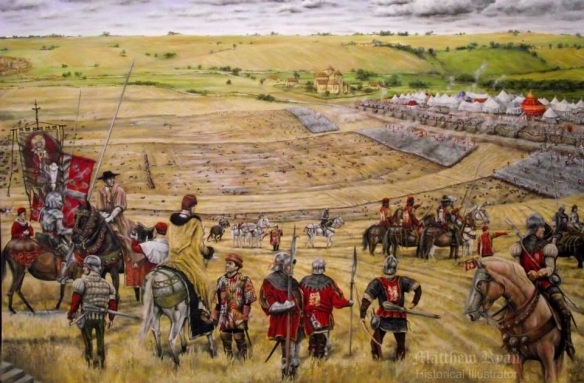

The Lancastrian court was at Coventry, as was common during this period, but on hearing of the Yorkist advance, King Henry and his supporters – who had already been raising troops – moved to Northampton. Initially, Henry may have lodged at Delapré Abbey, south of the town, although his army would have camped in the open. Henry was accompanied by a number of peers – the Duke of Buckingham, the Earl of Shrewsbury, and Lords Beaumont, Egremont, and Grey of Ruthin – although there had been no time to raise a truly formidable force. But the Lancastrians were confident they were capable of making a stand. By 10 July, when the large Yorkist army arrived on the scene, the Lancastrians had taken up a fortified position with their rear protected by the River Nene. They ‘ordained there a strong and mighty field […] armed and arrayed with guns’. Banks and ditches would have been dug to the front and the Lancastrians would have been well supplied with artillery from their arsenal at Kenilworth. Although the Yorkists outnumbered the Lancastrians, the army must have looked on their enemy’s strong position with trepidation.

The Yorkists’ propaganda had always stressed that their argument was with Henry’s courtiers, not with Henry himself. Therefore they needed to give the impression of wanting to present their case. Henry had now joined his army in the field. A delegation headed by Richard Beauchamp, Bishop of Salisbury, approached the Lancastrian camp, offering the Archbishop of Canterbury and Coppini as mediators. Perhaps Henry, even now, would have granted the Yorkist lords an audience but his noble supporters were in no mood to parley. The Duke of Buckingham was particularly belligerent. He has traditionally been regarded as a moderate influence, but by now he had lost all patience with the Yorkists. Buckingham angrily denounced the bishop’s delegation as ‘men of war’ – because they came with an armed guard – and curtly cut off their protestations to the contrary. ‘Forsooth,’ said the duke, ‘the Earl of Warwick shall not come to the King’s presence; if he comes he shall die.’ Yet remarkably, Warwick sent another herald, and it was not until this emissary was refused access to the King that the charade of negotiation finally came to an end. One last Yorkist messenger announced that ‘at two hours after noon he [Warwick] would speak with him or else die in the field’.

Conflict was now certain. Realistically, had it ever been in doubt? As was customary, the Yorkists ordained three ‘battles’, although quite what this meant in practice is not always clear. It is often assumed that armies during the Wars of the Roses were crudely split into three large units, probably because the sources rarely tell us more. It has been plausibly suggested that further organisation may have been provided, albeit in a rather haphazard way, by grouping the men according to lordships or localities. Yet evidence does exist to suggest that medieval battle plans – and dispositions – could be much more complex. For example, the surviving battle plans drawn up by the Marshal Boucicaut and by Duke John ‘the Fearless’ of Burgundy clearly demonstrate that tactical considerations were taken very seriously. It was also considered how an army should be organised when not made up of seasoned warriors. But on this occasion tactical factors were not crucial, although dispositions will be discussed more thoroughly below, when the sources allow this. The Battle of Northampton was partly to be decided by a factor sometimes neglected by historians, but which played a part in almost all of the battles and campaigns of the Wars of the Roses: namely, the weather. The Yorkists would also profit from an act of treachery. But what of Edward’s own role in the battle? It is contested in the sources. Most chroniclers agree that ‘little Fauconberg’ was accorded the honour of leading the vanguard, consisting of the men of Kent. According to Wavrin, Warwick and Edward then jointly ‘directed’ the rest of the army, although Whethamstede tells us that Edward led one of the three ‘battles’. At Northampton, the army probably looked to Warwick for overall direction, although it is clear that Edward held a position of responsibility. Perhaps Edward had already ‘won his spurs’ in the skirmish at Newnham Bridge, but now there was more at stake. What is certain is that here, for the first time, Edward would have stood under his own banner with a group of men looking to him for leadership.

According to Whethamstede, Warwick, Edward and Fauconberg made a simultaneous assault on the Lancastrian position, presumably hoping to win the day through sheer force of numbers. The assault took place in driving rain, which must have made the going difficult, and at around 400 yards the Yorkists would have come within range of the Lancastrians’ artillery. This was a critical moment: the Yorkists might suffer heavy casualties and panic would surely ensue … Yet, inexplicably, the Lancastrian guns did not fire. According to the English Chronicle, ‘the ordnance of the King’s guns availed not’, because they ‘lay deep in the water, and so were quenched, and might not be shot’. The Yorkists’ relief would have been countered by Lancastrian alarm. Worse was to come. There must have been archers in the Lancastrian camp but they made little impact and the Yorkists quickly arrived at the Lancastrians’ fortifications. Lord Grey of Ruthin was in command of the Lancastrian ‘vaward’, which would have been expected to offer fierce resistance. But in a quite extraordinary move, Grey changed sides and went over to the Yorkists:

the attacking squadrons came to the ditch before the royalist rampart and wanted to climb over it, which they could not do quickly because of the height [but] Lord Grey and his men met them and, seizing them by the hand, hauled them into the embattled field.

The Yorkists now poured into the Lancastrian camp. According to Wavrin, Edward’s own troops were the first inside. With their fortifications now useless, most Lancastrian soldiers seem to have thrown down their arms or taken flight. The Lancastrian nobles made a stand around King Henry’s tent but, assailed from all sides, they stood little chance. Buckingham, Shrewsbury, Beaumont and Egremont were all killed. King Henry himself was captured by an archer, Henry Mountfort. The Yorkist victory was complete.

Clearly Grey’s treachery was crucial: how can his actions be explained? The Yorkist English Chronicle argues that Grey was responsible for the ‘saving of many a man’s life’, but later commentators have been less kind. In the words of H.T. Evans, ‘in the sordid annals of even these sterile wars there is no deed of shame so foul’. Yet Grey’s motives remain shrouded in mystery. According to Wavrin, Grey’s treachery had been arranged in advance, but if this is true it seems curious that Grey did not receive any immediate benefits from his ‘foul’ deed. Much later he became Earl of Kent, although for now survival was his only reward. Perhaps, as R.I. Jack has suggested, Grey’s actions simply represent ‘an inspired gamble’ in the heat of the moment. But it is also a puzzle why Lord Grey was entrusted with the ‘vaward’ in the first place. He was not an especially important magnate, and, unlike Fauconberg on the other side, he did not have a military reputation. This is particularly significant bearing in mind that the other nobles present do not seem to have been adequately prepared for battle; another leader, such as Buckingham, or the warlike Egremont, would surely have offered more defiance.

The battle lasted barely half an hour. Some royalist troops appear to have drowned in the river Nene while trying to escape, but losses on both sides were slight. As at St Albans the Yorkists’ aim was to isolate and eliminate the Lancastrian leaders. Indeed, according to the English Chronicle, orders were given to spare the King and the commons, but to show no mercy to the lords and gentry. Probably neither Edward nor Warwick were heavily involved in the fighting; once it became clear the battle was won, and their chief rivals could not escape, doubtless their main concern was to ensure that the person of Henry VI was secured. This too was quickly achieved. Edward, as a soldier, was to face much greater challenges. Even so, his experience here may have strongly influenced his later conduct as both a strategist and a tactician. During the course of the French wars it had become received wisdom that defensive tactics would invariably prevail on the battlefield. Jean de Bueil, reflecting on his experience of fighting the English, counselled that ‘a formation on foot should never march forward, but should always hold steady and await its enemies …’ It is often suggested that the defensive approach adopted by York, at Ludford, and by Buckingham, at Northampton, was a legacy of their experience in France. For younger men such as Edward, however, the events at Northampton must have discredited the tactic of the entrenched encampment. If they did look to the Hundred Years’ War for models, they would find them in the careers of men such as John Talbot, whose success depended on audacity and speed, not on dogged defence.

Following the battle the captive Henry was treated, ostensibly at least, with the deference due to a king; both Edward and Warwick kneeled before him, acknowledged him as their sovereign, and Henry was led with ceremony into Northampton. Although it was later alleged that Coppini had threatened to excommunicate the Lancastrians if they did not submit, the bodies of the dead Lancastrian lords were treated with respect. Buckingham, for instance, received honourable burial at the Grey Friars’ Church; other victims were buried at St John’s Hospital. On 14 July the Yorkists headed back to London, where the Earl of Salisbury, ably assisted by Sir John Wenlock, was now besieging the Tower. With the approach of the Yorkist army, Lancastrian resistance in the Tower quickly came to an end. Scales surrendered the Tower on 19 July. Some of the defenders would later be executed, but Lord Scales negotiated safe passage for himself and Lord Hungerford. But the Tower garrison had fired cannon into the city, which had enraged the citizens. Scales tried to reach sanctuary at Westminster but was recognised by a woman, taken captive by a party of Thames boatmen, and brutally put to death. Perhaps surprisingly, the Yorkist leaders are said to have much regretted these events, although of course there were many connections that could, under different circumstances, have brought together those who we today refer to as ‘Yorkist’ or ‘Lancastrian’. Indeed, Lord Scales’ death is said to have caused Edward particular grief; he was Edward’s godfather.

Edward and the Nevilles were now masters of the kingdom, but in the absence of the Duke of York it was not possible to pursue any of their long-term objectives. York landed at Chester on 8 September, however, and from here he made leisurely but regal progress, his sword borne upright before him like a king. For the last ten years, all of York’s public statements had stressed that he was a loyal subject of Henry VI; his opposition was for the good of the ‘common weal’ and was not aimed at King Henry himself. But now York would propose a more radical solution to England’s problems. He reached London on 15 October and upon arriving at Westminster Palace – where a Parliament had been hastily assembled – he immediately made his intentions clear. York placed his hand on the throne and looked for acclamation. But he was met with stunned silence. The Archbishop of Canterbury made a clumsy attempt at a greeting, asking York if he wished to see the King. York’s reply was proud and haughty: ‘I know of no one in the realm who would not more fitly come to me than I to him.’ Then he stormed out of the room, leaving consternation in his wake.

According to Wavrin, York’s actions took Edward and the Nevilles by surprise, and they were appalled. Warwick went to remonstrate with the duke:

and so [Warwick] entered the duke’s chamber and found him leaning on a dresser. When the duke saw him he came forward and they greeted each other and there was some strong language between them, for the earl told the duke that the lords and the people disapproved of his intention to depose the King. While they were talking [Edmund] Earl of Rutland entered, the brother of the Earl of March, and he said to Warwick: ‘Dear cousin, do not be angry, for you know that it belongs to my father, and he shall have it.’ To this, the Earl of March, who was present, responded and said to the Earl of Rutland, ‘Brother, offend nobody, for all shall be well.’ After these words, when the Earl of Warwick had heard the duke’s wishes, he left in anger without taking leave of anybody, except the Earl of March, whom he asked very kindly to come the next day to London, where a council meeting would be held. March said he would not fail to be there.

This is a fascinating passage. It provides evidence of a rapport between Warwick and Edward, which had presumably developed in exile, but also evidence of Edward’s growing influence, which was to a certain extent independent of York or Warwick. Wavrin’s account has not been generally regarded as reliable, however. Were Edward and Warwick really surprised or appalled by York’s actions? It seems extremely unlikely. Nevertheless, it may be that Warwick, ever the politician, quickly realised that the lords were still reluctant to depose Henry VI. Edward, a much more subtle and sensitive man than his father, would surely have reached the same conclusion. Perhaps, then, the cause of the arguments reported by Wavrin was not that Duke Richard had sought the throne, but that he had (literally) shown his hand too soon.

In truth there were flaws and inconsistencies in the claims of both York and Lancaster. The lords, who were mindful of the oaths they had sworn to Henry but also of the power that York now held, eventually offered a curious compromise. York reluctantly agreed to the terms of the ‘Act of Accord’, which was similar to the Treaty of Troyes, whereby Henry would remain king for the rest of his life, but thereafter the crown would pass to York and his descendants. Henry, of course, had little choice but to acquiesce, although his queen was still at large and would scarcely have been expected to honour such an agreement. Margaret and her adherents were scattered – the Queen had herself fled to Wales in precarious circumstances – but she quickly took steps to gather her supporters. By early December York was preparing for war. The Yorkists split their existing forces, although of course they expected to raise fresh troops for the struggle to come. York went north, Warwick was to remain in London, and Edward was sent to the Marches; it was to be his first independent command.