In 406 the East Germanic Vandals and their tribal confederates, including Germanic Suebi and Iranian Alans, crossed the Rhine. After an initial defeat at the hands of the Franks, the Vandals enlisted Alan support and smashed their way into Gaul, plundering the countryside mercilessly as they advanced into the south. In the early 420s Roman pressure forced the Vandals into southern Spain where the newcomers faced a Roman-Gothic alliance; this threat the Vandals managed to defeat, but there could be no peace. Under their fearless and brilliant war leader Geiseric (428–77), whose fall from a horse had made him lame, the Vandals sought shelter across the Mediterranean; their long exodus led as many as 80,000 of them to Africa where, they believed, they could shelter themselves from Roman counterattack. They commandeered ships and ferried themselves across the straits to Tangiers, in the Roman province of Mauretania Tingitana.

There the local dux had few men to oppose Geiseric, who swept him aside and, after a year’s plundering march, in 410 reached the city of Hippo Regius (modern Annaba in Algeria). There one of the great luminaries of Christian history lay dying: Augustine of Hippo, bishop of the city and church father. The Vandals stormed the city and spread death and sorrow, but Augustine was spared the final horror; he died on August 28, 430, about a year before the Vandals returned and finally overcame the city. By then Vandal aggression had prompted a large-scale imperial counteroffensive led by count Boniface. In 431 an imperial expedition from the east led by the generalissimo Aspar joined forces with Boniface but suffered defeat and had to withdraw in tatters. The future eastern emperor Marcian (d. 457) served in the expedition and fell into Vandal hands. He helped broker the resulting peace, which recognized Vandal possession of much of Roman Numidia, the lands of what is now eastern Algeria. The Romans licked their wounds but could in no way accept barbarians in possession of one of the most productive cornlands and who threatened the richest group of provinces of the whole of the Roman west. In 442 the emperor Theodosius II dispatched a powerful force from the east with the aim of dislodging the Vandals. It too was defeated and in 444 the Romans were forced to recognize Vandal control over the provinces of Byzacena, Proconsularis, and Numidia, the regions today comprising eastern Algeria and Tunisia—rich districts with vast farmland and numerous cities. In 455 the Vandals sacked Rome, the second time the great city had suffered sack in fifty years, having been plundered by Alaric in 410. The eastern emperor Marcian had his own problems to deal with, namely the Huns, and therefore sent no retaliatory expedition.

Instead, Constantinople finally responded in 461 in conjunction with the capable western emperor, Majorian (457–61), but Majorian’s crossing to Africa from Spain was frustrated by traitors in his midst who burned the expeditionary ships and undid the western efforts. By this time the Vandals had established a powerful fleet and turned to piracy; they threatened the Mediterranean coastlands as far as Constantinople itself. In 468 the emperor Leo I launched another massive attack against Vandal North Africa under the command of his brother-in-law Basiliskos; Prokopios records that the expedition cost the staggering sum of 130,000 lbs. of gold. The expedition began promisingly enough. Leo sent the commander Marcellinus to Sardinia, which was easily captured, while another army under Heraclius advanced to Tripolis (modern Tripoli) and captured it. Basiliskos, however, landed somewhere near modern Hammam Lif, about 27 miles from Carthage. There he received envoys from Geiseric who begged him to wait while the Vandals took counsel among themselves and determined the course of negotiations. While Basiliskos hesitated, the Vandals assembled their fleet and launched a surprise attack using fire ships and burned most of the anchored Roman fleet to cinders. As his ship was overwhelmed, Basiliskos leaped into the sea in full armor and committed suicide.

The stain on Roman honor from the Basiliskos affair was deep; rumors abounded of his incompetence, corruption, or outright collusion with the enemy. The waste of treasure and the loss of life was so severe that the eastern empire made no more effort to dislodge the Vandals and to recover Africa. As the fifth century deepened and the Hunnic threat receded, the east settled into an uneasy relationship with the former imperial territories of North Africa, trading and exchanging diplomatic contacts, but never allowing the Vandals to think that Africa was rightly theirs. The emperor Zeno established an “endless peace” with the Vandal foe, binding them with oaths to cease aggression against Roman territory. Upon the death of Geiseric, his eldest son Huneric (477–84) ruled over the Vandals; he is remembered as a cruel persecutor of Catholics in favor of the heretical form of Christianity, Arianism, practiced by the Vandals and Alans. Huneric’s son with his wife Eudoxia, the daughter of the former western emperor Valentinian III, was Hilderic, who claimed power in Africa in 523. Under Hilderic, relations with Constantinople warmed considerably. Hilderic himself had a personal bond with Justinian from the time the latter was a rising talent and force behind the throne of his uncle, the emperor Justin (518–27), and in a policy designed to appease local Africans and the empire, Catholics were left unmolested; many Vandals converted to the orthodox form of Christianity. The Vandal nobility found their situation threatened, as one of the key components of their identity, Arianism, was under attack; assimilation and disintegration, they reasoned, were sure to follow. When, in 530, Hilderic’s younger cousin Gelimer overthrew the aged Vandal king it was with the support of the majority of the elites. Hilderic died in prison as Justinian monitored events from Constantinople with dismay. Roman diplomatic attempts to restore Hilderic failed. But Justinian was unable to act because war with Persia had commenced and his forces were tied down in Syria. By 532, Justinian sealed peace with Persia, freeing his forces and their young general Belisarios, the victor in 530 over the Persian army at Dara, to move west.

On the heels of the signing of the peace with Persia in 532, Justinian announced to his inner circle his intentions to invade the Vandal kingdom. According to a contemporary witness and one in a position to know, the general Belisarios’s secretary Prokopios, the news was met with dread. Commanders feared being selected to lead the attack, lest they suffer the fate of prior expeditions, while the emperor’s tax collectors and administrators recalled the ruinous expense of Leo’s campaign that cost vast amounts of blood and treasure. Allegedly the most vocal opponent was the praetorian prefect John the Cappadocian, who warned the emperor of the great distances involved and the impossibility of attacking Africa while Sicily and Italy were in the hands of the Ostrogoths. Eventually, we are told, a priest from the east advised Justinian that in a dream he foresaw Justinian fulfilling his duty as protector of the Christians in Africa, and that God himself would join the Roman side in the war. Whatever the internal debates and the role of faith, there was certainly a religious element to Roman propaganda; Catholic bishops stirred the pot by relating tales of Vandal atrocities against the faithful. Justinian overcame whatever logistical and military misgivings he possessed through belief in the righteousness of his cause.

It could not have been lost on the high command in Constantinople that Justinian’s plan of attack was identical to Leo’s, which was operationally sound. Imperial agents responded to (or more likely incited) a rebellion by the Vandal governor of Sardinia with an embassy that drew him to the Roman side. Justinian supported another revolt, this one by the governor of Tripolitania, Prudentius, whose Roman name suggests he was not the Vandal official in charge there. Prudentius used his own troops, probably domestic bodyguards, armed householders, and Moors, to seize Tripoli. He then sent word to Justinian requesting aid and the emperor obliged with the dispatch of a force of unknown size under the tribune Tattimuth. These forces secured Tripoli while the main expeditionary army mustered in Constantinople.

The forces gathered were impressive but not overwhelming. Belisarios was in overall command of 15,000 men and men attached to his household officered most of the 5,000 cavalry. John, a native of Dyrrachium in Illyria, commanded the 10,000 infantry. Foederati included 400 Heruls, Germanic warriors who had migrated to the Danubian region from Scandinavia by the third century. Six hundred “Massagetae” Huns served—these were all mounted archers and they were to play a critical role in the tactics of the campaign. Five hundred ships carried 30,000 sailors and crewmen and 15,000 soldiers and mounts. Ninety-two warships manned by 2,000 marines protected the flotilla, the largest seen in eastern waters in at least a century. The ability of the Romans to maintain secrecy was astonishing, for strategic surprise was difficult to achieve in antiquity; merchants, spies, and travelers spread news quickly. Gelimer was clearly oblivious to the existence of the main Roman fleet; apparently an attack in force was inconceivable to him and he saw the Roman ambitions confined to nibbles at the edge of his kingdom. The Vandal king sent his brother Tzazon with 5,000 Vandal horse and 120 fast ships to attack the rebels and their Roman allies in Sardinia.

It had been seven decades since the Romans had launched such a large-scale expedition into western waters, and the lack of logistical experience told. John the Cappadocian economized on the biscuit; instead of being baked twice, the bread was placed near the furnaces of a bathhouse in the capital; by the time the fleet reached Methone in the Peloponnese, the bread was rotten and 500 soldiers died from poisoning. The water was also contaminated toward the end of the voyage and sickened some. After these difficulties, the fleet landed in Sicily near Mount Aetna. In 533 the island was under the control of the Ostrogothic kingdom of Italy, and through diplomatic exchanges the Ostrogoths had been made aware of the Roman intentions of landing there to procure supplies and use the island as a convenient springboard for the invasion. Prokopios reports the psychological effect of the unknown on the general and his men; no one knew the strength or battle worthiness of their foe, which caused considerable fear among the men and affected morale. More terrifying, though, was the prospect of fighting at sea, of which the vast majority of the army had no experience. The Vandal reputation as a naval power weighed heavily on them. In Sicily, Belisarios therefore dispatched Prokopios and other spies to Syracuse in the southeast of the island to gather intelligence about the disposition of the Vandal navy and about favorable landing spots on the African coast. In Syracuse, Prokopios met a childhood acquaintance from Palestine, a merchant, whose servant had just returned from Carthage; this man informed Prokopios that the Vandal navy had sailed for Sardinia and that Gelimer was not in Carthage, but staying four days’ distance. Upon receiving this news, Belisarios embarked his men at once and sailed, past Malta and Gozzo, and anchored unopposed at Caput Vada (today Ras Kaboudia in east-central Tunisia). There the high command debated the wisdom of landing four days’ march or more from Carthage in unfamiliar terrain where lack of provisions and water and exposure to enemy attack would make the advance on the Vandal perilous. Belisarios reminded his commanders that the soldiers had openly spoken of their fear of a naval engagement and that they were likely to flee if they were opposed at sea. His view carried the day and they disembarked. The journey had taken three months, rendering it all the more remarkable that news of the Roman expedition failed to reach Gelimer.

The cautious Belisarios followed Roman operational protocol; the troops established a fortified, entrenched camp. The general ordered that the dromons, the light, fast war galleys that had provided the fleet escort, anchor in a circle around the troop carriers. He assigned archers to stand watch onboard the ships in case of enemy attack. When soldiers foraged in local farmers’ orchards the next day, they were severely punished and Belisarios admonished the army that they were not to antagonize the Romano-African population, whom he hoped would side with him against their Vandal overlords.

The army advanced up the coastal road from the east toward Carthage. Belisarios stationed one of his boukellarioi, John, ahead with a picked cavalry force. Ahead on the army’s left rode the 600 Hun horse archers. The army moved 80 stadia (about 8 miles) each day. About 35 miles from Carthage, the armies made contact; in the evening when Belisarios and his men bivouacked within a pleasure park belonging to the Vandal king, Vandal and Roman scouts skirmished and each retired to their own camps. The Byzantines, crossing to the south of Cape Bon, lost sight of their fleet, which had to swing far to the north to round the cape. Belisarios ordered his admirals to wait about 20 miles distant from the army and not to proceed to Carthage where a Vandal naval response might be expected.

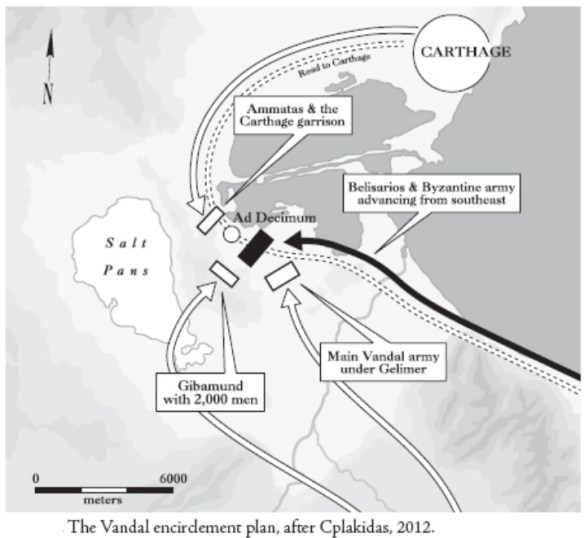

Gelimer had, in fact, been shadowing the Byzantine force for some time, tracking them on the way to Carthage where Vandal forces were mustering. The king sent his nephew Gibamund and 2,000 Vandal cavalry ahead on the left flank of the Roman army. Gelimer’s strategy was to hem the Romans between his forces to the rear, those of Gibamund on the left, and reinforcements from Carthage under Ammatas, Gelimer’s brother. The plan was therefore to envelop and destroy the Roman forces. Without the 5,000 Vandal troops sent to Sardinia, the Vandal and Roman armies were probably about equal in strength. Around noon, Ammatas arrived at Ad Decimum, named from its location at the tenth milestone from Carthage. In his haste, Ammatas left Carthage without his full complement of soldiers and arrived too early by the Vandals’ coordinated attack plan. His men encountered John’s boukellarioi elite cavalry.

Outnumbered, the Vandals fought valiantly; Prokopios states that Ammatas himself killed twelve men before he fell. When their commander perished, the Vandals fled to the northwest back toward Carthage. Along their route they encountered penny packets of their countrymen advancing toward Ad Decimum; the retreating elements of Ammatas’s forces panicked these men who fled with them, pursued by John to the gates of the city. John’s men cut down the fleeing Vandals in great number, bloody work far out of proportion to his own numbers. About four miles to the southeast, the flanking attack of the 2,000 Vandal cavalry under Gibamund encountered the Hunnic flank guard of Belisarios. Though they were outnumbered nearly four to one, the 600 Huns had the advantage of tactical surprise, mobility, and firepower. The Vandals had never experienced steppe horse archers; terrified by the reputation and the sight of them, Gibamund and his forces panicked and ran; the Huns thus decimated the second prong of Gelimer’s attack.

Belisarios had still not been informed of his lieutenant’s success when at the end of the day his men constructed the normal entrenched and palisaded camp. Inside he left the baggage and 10,000 Roman infantry, taking with him his cavalry force and boukellarioi with the hopes of skirmishing with the enemy to determine their strength and capabilities. He sent the four hundred Herul foederati as a vanguard; these men encountered Gelimer’s scouts and a violent clash ensued.

The Heruls mounted a hill and saw the body of the Vandal army approaching. They sent riders to Belisarios, who pushed forward with the main army—Prokopios does not tell us, but it seems that this could only have been the cavalry wing, since only they were drawn up for action. The Vandals drove the Heruls from the hill and seized the high point of the battlefield. The Heruls fled to another portion of the vanguard, the boukellarioi of Belisarios, who, rather than hold fast, fled in panic.

Gelimer made the error of descending the hill; at the bottom he found the corpses of the Vandals slain by John’s forces, including Ammatus. Upon seeing his dead brother, Gelimer lost his wits and the Vandal host began to disintegrate. Though Prokopios does not mention it, there was more in play; the string of corpses on the road to Carthage informed the king that his encirclement plan had failed and he now faced a possible Roman encirclement. He could not be certain that a Roman force did not bar the way to Carthage. Thus, as Belisarios’s host approached, the Vandal decision to retreat to the southwest toward Numidia was not as senseless as Prokopios claimed. The fighting, which could not have amounted to much more than running skirmishing as the Vandals withdrew, ended at nightfall.

The next day Belisarios entered Carthage in order; there was no resistance. The general billeted his soldiers without incident; the discipline and good behavior of the soldiers was so exemplary that Prokopios remarked that they purchased their lunch in the marketplace the day of their entry to the city. Belisarios immediately started repairs on the dilapidated city walls and sent scouts to ascertain the whereabouts and disposition of Gelimer’s forces. Not much later his men intercepted messengers who arrived from Sardinia bearing news of the defeat of the rebel governor at the hands of the Vandal general Tzazon. Gelimer and the Vandal army, which remained intact, were encamped on the plain of Bulla Regia, four days’ march south of Carthage. The king sent messengers to Tzazon in Sardinia, and the Vandal army there returned and made an uncontested landing west of Carthage and marched overland to Bulla Regia where the two forces unified. Belisarios’s failure to intercept and destroy this element of the Vandal force when it landed was a major blunder that Prokopios passes over in silence.

Once Gelimer and Tzazon unified their forces, they moved on Carthage, cut the main aqueduct, and guarded the roads out of the city. They also opened negotiations with the Huns in Roman service, whom they enticed to desert, and they attempted to recruit fifth columnists in the city to help their cause.

The two armies encamped opposite one another at Tricamarum, about 14 1/2 miles south of Carthage. The Vandals opened the engagement, advancing at lunch time when the Romans were at their meal. The two forces drew up against one another, with a small brook running between the front lines. Four thousand five hundred Roman cavalry arrayed themselves in three divisions along the front; the general John stationed himself in the center, and Belisarios came up behind him with 500 household guards. The Vandals and their Moorish allies formed around Tzazon’s 5,000 Vandal horsemen in the center of the host. The two armies stared one another down, but since the Vandals did not take the initiative, Belisarios ordered John forward with picked cavalry drawn from the Roman center. They crossed the stream and attacked the Vandal center, but Tzazon and his men repulsed them, and the Romans retreated. The Vandals showed good discipline in their pursuit, refusing to cross the stream where the Roman force awaited them. John returned to the Roman lines, selected more cavalry, and launched a second frontal assault. This, too, the Vandals repulsed. John retired and regrouped and Belisarios committed most of his elite units to a third attack on the center. John’s heroic final charge locked the center in a sharp fight. Tzazon fell in the fighting and the Vandal center broke and fled, joined by the wings of the army as the Romans began a general advance. The Romans surrounded the Vandal palisade, inside which they took shelter along with their baggage and families. In the clash that opened the battle of Tricamarum in mid- December 533, the Romans counted 50 dead, the Vandals about 800.

As Belisarios’s infantry arrived on the battlefield, Gelimer understood that the Vandals could not withstand an assault on the camp by 10,000 fresh Roman infantry. Instead of an ordered retreat, though, the Vandal king fled on horseback alone. When the rest of the encampment learned of his departure, panic swept the Vandals, who ran away in chaos. The Romans plundered the camp and pursued the broken force throughout the night, enslaving the women and children and killing the males. In the orgy of plunder and captive taking, the cohesion of the Roman army dissolved completely; Belisarios watched helplessly as the men scattered and lost all discipline, enticed by the richest booty they had ever encountered. When morning came, Belisarios rallied his men, dispatched a small force of 200 to pursue Gelimer, and continued to round up the Vandal male captives. The disintegration of the Vandals was clearly complete, since the leader offered a general amnesty to the enemy and sent his men to Carthage to prepare for his arrival. The initial pursuit of Gelimer failed, and Belisarios himself led forces to intercept the king, whose existence still threatened a Vandal uprising and Moorish alliances against the Roman occupiers. The general reached Hippo Regius where he learned Gelimer had taken shelter on a nearby mountain among Moorish allies. Belisarios sent his Herul foederati under their commander Pharas to guard the mountain throughout the winter and starve out Gelimer and his followers.

Belisarios garrisoned the land and sent a force to Sardinia which submitted to Roman control and sent another unit to Caesarea in Mauretania (modern Cherchell in Algeria). In addition, the general ordered forces to the fortress of Septem on the straits of Gibraltar and seized it, along with the Balearic Islands. Finally he sent a detachment to Tripolitania to strengthen the army of Prudentius and Tattimuth to ward off Moorish and Vandal activity there. Late in the winter, facing deprivation and surrounded by the Heruls, Gelimer negotiated his surrender and was taken to Carthage where Belisarios received him and sent him to Constantinople.

Roman victory was total. The Vandal campaign ended with a spectacular recovery of the rich province of Byzacium and the riches of the African cities and countryside the Vandals had held for nearly a century. Prokopios is reserved in his praise for his general, Belisarios, and for the performance of the Roman army as a whole, laying the blame for Vandal defeat at the feet of Gelimer and the power of Fortune, rather than crediting the professionalism or skill of the army commanders and rank and file. The Romans clearly made several blunders—chief among these the failure to intercept Tzazon’s reinforcing column, and Belisarios’s inability to maintain discipline in the ranks upon the plundering of the Vandal encampment at Tricamarum. On balance, though, the army and the state had performed well enough. The work of imperial agents in outlying regions of Tripolitania and Sardinia distracted the Vandals and led them to disperse their forces. Experienced Roman soldiers who had just returned from years of hard fighting against the Persians proved superior to their Vandal enemy in hand-to-hand fighting. Indeed, they had proved capable of meeting and destroying much larger enemy contingents. Belisarios’s leadership, maintenance of morale, and (apart from the Tricarmarum incident) excellent discipline accompanied his cautious, measured operational decisions that conserved and protected his forces. Roman losses were minimal in a campaign that extended imperial boundaries by more than 50,000 square kilometers (19,300 square miles) and more than a quarter million subjects. The empire held its African possessions for more than a century until they were swept under the rising Arab Muslim tide in the mid-seventh century.