The worst omen of 1937 was the ministerial change in May: Stanley Baldwin retired, and Neville Chamberlain became Prime Minister, with Sir John Simon as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Anthony Eden was Foreign Secretary. A new card had already been introduced into the political pack: a Minister for Coordination of Defence. Sir Thomas Inskip took up that office in March 1936, and held it until January 1939. Chamberlain, of course, was the dominant personality, as he had been as Chancellor; the personal preeminence of that strange man is an important element in the politics of the time. He had that strength which comes from a remarkable degree of self-assurance; unfortunately, this quality itself was in his case founded neither on deep knowledge nor on particular expertise, but all too often on pure ignorance. We have seen how in 1934 he unhesitatingly “took charge” of defence requirements. As Chancellor of the Exchequer he showed no diffidence whatever in challenging the opinions of the Chiefs of Staff on strategic and other military matters – indeed, he attached little weight to those opinions. Now, as Premier, he took the same position over foreign policy, ignoring, bypassing and brushing aside the Foreign Secretary. The consequences we know too well; the reasons continue to be disputed. I would suggest three main strands in Chamberlain’s approach, and its outcome, the policy called “Appeasement”.

The word itself has been subjected in recent years to sharp and sceptical scrutiny, yet as a political reality it does not readily lose force. Appeasement was, in fact, a disastrously effective political position, and since Chamberlain was its prime exponent he has been accordingly attacked with bitterness, and sinister motives have been attributed to him as leader of the “Guilty Men”. Recent research presents a different picture; Chamberlain’s personal attitude towards the dictators does not now appear all that different from Eden’s or Churchill’s. As regards the Nazis, as Dr Wrench says, “he regarded them with hatred and contempt”; such episodes as the brutal murder of the Austrian Chancellor Dollfuss sickened him no less than anyone else. Regarding Mussolini, he clung to the idea of keeping Italian Fascism and Nazism apart by friendly gestures long after any such possibility had evaporated. But fundamentally, the conflict between the appeasers and the resisters was one of method rather than intention.

Chamberlain’s methods were dictated, first, by an attitude towards all things military which was far from common in men of his age and background. Neville Chamberlain was born in 1869; 31 years of his life had passed in the nineteenth century – the formative years. This, and his Birmingham business upbringing, were decisive:

The school of thought which remained predominant throughout the great industrial epoch bitterly resented the assumption, made by certain classes, that the profession of arms was more honourable in its nature than commerce and other peaceful pursuits. Inefficiency, indifference, idleness, trifling and extravagance were a standing charge against soldiers as a class. The soldier, according to Political Economy, was occupied in a non-productive trade, and therefore it was contrary to the principles of that science to waste more money on him than could be avoided.

The experience of the First World War seemed, to men like Chamberlain, to underline every word of this text; it positively hurt to put large sums of money in the hands of military profligates of doubtful competence. And it hurt all the more because – this is the second strand – Chamberlain, all his supporters and above all the senior officials of the Treasury, had an immense, overwhelming respect for money itself. They really did believe, as Brian Bond says, that “economic stability was one of the cornerstones of the nation’s defence structure and an integral part of the defensive strategy.” This would have serious implications for Defence planning, particularly affecting the RAF, as we shall see. Finally, in Chamberlain’s make-up, and perhaps the decisive element, was sheer conceit, the self-assurance referred to above, which Dr Wrench calls “his unassailable belief in his own rectitude”. All in all, it was a formidable combination.

It was, then, with more money in its pocket than it would recently have dared to dream of, but still not enough, and under the eagle eye of a premier innately hostile to military spending, that the RAF approached the last crisis before the war. The key word, of ill omen, during this period was “parity”. Ever since Hitler had made his startling boast of air equality to Simon and Eden in March 1935, the fear of German air power had been growing in Britain. Linked to the theory of the “knock-out blow”, it had most serious effects in decision-making circles. In October 1936 the Joint Planning Committee of the Chiefs of Staff examined the probable course of a war starting in 1939, and pronounced:

We are convinced that Germany would plan to gain her victory rapidly. Her first attacks would be designed as knock-out blows. It is clear that in a war against us the concentration, from the first day of war, of the whole German air offensive ruthlessly against Great Britain would be possible. It would be the most promising way of trying to knock this country out.

The Joint Planners then proceeded to draw a picture of casualties mounting to 150,000 within a week, internal security breaking down, and “angry and frightened mobs of civilians” trying to sabotage RAF aerodromes. The hysterical reactions of civilians to the air raids of the First World War were bearing poisoned fruit; fear of a breakdown of civilian morale was very strong at this time. One of the country’s most famous military experts, Major-General J. F. C. Fuller, who was passing through a period of searching doubt about democracy’s survival capacity, was writing of air power achieving victory “through terror and panic”; after even one air raid, said Fuller,

London for several days will be one vast raving Bedlam, the hospitals will be stormed, traffic will cease, the homeless will shriek for help, the city will be a pandemonium. What of the Government at Westminster? It will be swept away by an avalanche of terror.

The Joint Planning Committee has been taken to task for its “disgraceful estimate of the guts of their fellow-countrymen”. The Air representative on it was Group Captain A. T. (later Sir Arthur) Harris; the naval spokesman was Captain T. S. V. Phillips, who was to fall victim to Japanese air power in HMS Prince of Wales, and for the Army Colonel Sir Ronald Adam, Adjutant-General, 1941-46. Their prognostications seem unduly alarmist with the hindsight that 1939-45 was to bring, but in those last pre-war years they were in good company. And as Marshal of the RAF Sir John Slessor said, it must be remembered that “before 1939 we really knew nothing about air warfare”.

Slessor became Deputy Director (in effect Director) of Plans at the Air Ministry in May 1937. He very soon became alarmed at what he was able to discover on the subject of air parity with Germany, the more so in view of the limping progress of British industry with the production of new aircraft. Air Ministry Intelligence estimated that Germany already had “800 bombers technically capable of attacking objectives in this country from bases on German soil”; by September, 738 were identified in units, but the estimate of those actually serviceable was put at 500-600. In addition, Italy was credited with a long-range striking force of over 400 bombers.

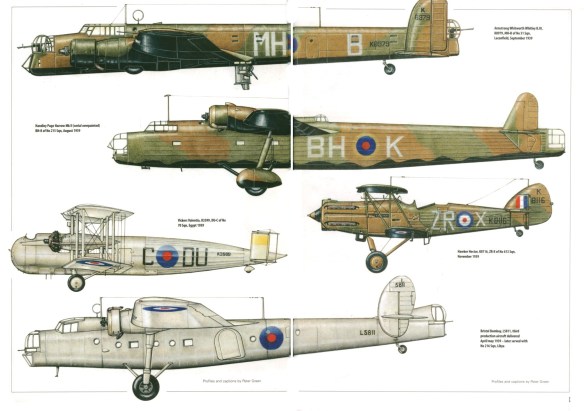

Against this we could mobilize in Bomber Command only ninety-six corresponding “long-range” bombers – thirty-six each of Blenheims and Wellesleys and twelve each of Battles and Harrows, pretty poor stuff compared with the Ju 86, He 111 and Do 17, of which we knew some 250 were mobilizable in Germany. Our nominal bomber strength was 816 in the Metropolitan Air Force; but the remaining 700 odd were mostly obsolete short-range types like Heyfords, Hinds, Audax and Ansons, and in any event over 30 per cent of the squadrons would have to be “rolled up” on mobilization to provide some reserves for the remainder.

Here was something to keep one awake at night!

Slessor did not let grass grow under his feet; on September 3 (interesting date) he and his fellow Deputy Directors submitted a paper to the CAS in which they said:

…the Air Staff would be failing in their duty were they not to express their considered opinion that the Metropolitan Air Force in general, and the Bomber Command in particular, are at present almost totally unfitted for war; that, unless the production of new and up-to-date aircraft can be expedited, they will not be fully fit for war for at least two and a half years; and that even at the end of that time, there is not the slightest chance of their reaching equality with Germany in first-line strength if the present German programmes are fulfilled…

Newall and Swinton were impressed by this forthright language, and the Air Staff was requested to draw up a scheme to produce, in Swinton’s words, “what as a General Staff you consider is militarily the proper insurance for safety, leaving it to the Cabinet to decide the extent to which the programme should be carried out”. The result was Scheme “J” (October 1937), “in many respects the best of all the schemes submitted”.

Scheme “J” proposed a bomber force of 90 squadrons (as compared with 70 in Scheme “F”) of which 64 would be heavy and 26 medium (as compared with 20 heavy and 65 medium in the abortive Scheme “H”). The first-line strength (1,442) was actually slightly lower than that proposed in Scheme “H”, but the aircraft were to be more powerful and the figure was real – not dependent on juggling with reserves or overseas Commands. There was also better provision for reserves within the scheme. Scheme “J” was due for completion by the spring of 1940 – if agreed. It had, however, two snags: first, it involved the mobilization of industry, and even with the lowering stormclouds of 1937 neither the Government nor the nation was yet ready to go that far. Secondly, the Minister for Coordination of Defence recoiled from the cost – and in doing so he used the argument of the knock-out blow to challenge the Air Staff’s view of strategy:

If Germany is to win she must knock us out within a comparatively short time owing to our superior staying power. If we wish our forces to be sufficient, to deter Germany from going to war, our forces – and this applies to the air force as much as to the other Services – must be sufficiently powerful to convince Germany that she cannot deal us an early knock-out blow. In other words, we must be able to confront the Germans with the risks of a long war, which is the one thing they cannot face.

The RAF’s role, argued Inskip, “is not an early knock-out blow… but to prevent the Germans from knocking us out”. He was not, he insisted, arguing for nothing but fighters: That would be an absurdity. My idea is rather that in order to meet our real requirements we need not possess anything like the same number of long-range bombers as the Germans – the numbers of heavy bombers should be reduced. Pursuing this line of thought, he suggested substituting “a larger proportion of light and medium bombers for our very expensive heavy bombers”. This, of course, flew in the face of all expert thinking; the whole development of modern aircraft – the very power of the new fighters themselves – was forcing bombers (except for specialized purposes) to become larger and larger. As it was, the outbreak of war found the RAF with too many light bombers of practically no value; Inskip’s suggestion would have compounded that disastrous condition. But Inskip was not really thinking about tactics and strategy; like too many of his Government colleagues, he was thinking above all of expense – and in this he received strong support from the Prime Minister, who stressed the need for economic stability once again. So Scheme “J” was referred back for cuts to make it cheaper – embodied in Scheme “K” of January 1938. But this never left the ground, because 1938 was the year when everything began to fall apart.

The first sign of the new bad times was the German occupation of Austria in March – once more in flat defiance of the Treaty of Versailles. More significant but not yet apparent was a German strategic advantage which became clearer as the Czech crisis developed only a few weeks later. Czechoslovakia’s powerful frontier defences against Germany were now outflanked by the open 250 miles of what had been the Austrian frontier, a fatal weakening. More blood-curdling to British opinion, however, at this stage, was the bombing of Barcelona between March 16 and 18, chiefly by Italian aircraft; some 1,300 people were killed and about 2,000 wounded – a total not vastly different from Britain’s in the whole of the First World War. And it was in London that the Barcelona raids made a significant impact; it was officially calculated, on the basis of these losses, that one ton of bombs would produce 72 casualties. Later, however, taking all raids on Barcelona into account, it appeared that the average number of people killed by a ton of bombs was three and a half. “This new casualty ratio was not apparently substituted in the British Home Office plans for the earlier and more drastic figures.”

This example of what air power could do in only three days seemed to bear out all the prognostications of the knock-out blow, and was prominent in the minds of public men and public opinion as the Czechoslovakian crisis built up through the summer of 1938. The Barcelona raids denoted a deep advance into the comfortless future, with every probability of worse to come. Yet calm examination of what history had already revealed about the subject of bombing could have offered some encouragement – if permitted. But just as the very small number of people killed by air action in Britain between 1915 and 1918 was ignored (as was the fact that even in 1917 improved techniques of air defence had made the Germans abandon daylight bombing), so now in 1938-39 there appears to have been no attempt to put Spanish air raid losses into any true perspective. Admittedly, this would not have been an easy task; but it was important. Hugh Thomas’s calculations, which to the best of my knowledge have not been overthrown, indicate that probably some 14,000 people were killed by air action in the Republican zones during the whole war, and possibly another 1,000 or so in the Nationalist – out of a grand total of approximately half a million dead; in other words, air raids accounted for about three per cent. Even if interim figures pointing towards this conclusion had been discovered and proclaimed, however, it is doubtful whether they would have won any wide acceptance, running as they did absolutely counter to the prophecies of the most respected pundits and the most alarmist science-fiction writers. As Sir John Slessor said many years later:

We may have been wrong about the knock-out blow; I still do not believe anyone is justified in saying we were certainly wrong there. And at least no one should judge the men of 1938 without understanding that that was the atmosphere in which decisions were made.