Historians are still puzzled by Louis’s decision to make such a surprising diversion, but more of them are now inclined to accept the report that he had been led to believe that the ruler of Tunis would convert to Christianity if he made a demonstration before his town. The crusade’s destination, or diversion, seems to have been kept secret until the fleet assembled off Sardinia before the run across to the North African coast, but when they got there the troops did very little fighting. The ruler of Tunis gave no sign of desiring baptism and retired behind his walls, and while Louis’s army camped on the site of ancient Carthage, disease reduced the troops more effectively than any amount of Greek fire, swords or mangonels. The French died like flies. Louis had landed on 18 July 1270 and within a few weeks his son, the Count of Nevers, the youth who had been born at Damietta during his last crusade, had succumbed to dysentery or typhoid. Louis himself expired on 25 August just as his brother, Charles of Anjou, the new king of Sicily, arrived.

Charles, who was noticeably less saintly than Louis, was in dispute with the Emir of Tunis over trading arrangements between their two countries – the emir was also sheltering exiles from Sicily – and a treaty with Tunis, obviously to Charles’s advantage, was now negotiated. But Charles, having found the crusade army leaderless and in desperate straits, abandoned all thoughts of going on to Acre. Poor Louis! It was reported that on the night before he died he whispered the words, ‘Jerusalem, Jerusalem’.

The Lord Edward, heir to Henry III of England, who had also taken the Cross, turned up in Tunisia with his small army of about 1,000 men just as the French were leaving. He decided to go on to Acre where he was later joined by his brother, Edmund of Lancaster. Conditions in the Kingdom of Jerusalem in 1271 were almost as depressing as those which had been engendered by the collapse of Louis’s crusade. Edward was successful in getting the Mongols to distract Baybars for a short time but the Mongol ruler, Abaga, had his own problems in Anatolia and soon withdrew. Edward found that the Latin states had no consistent policy towards the Mamluk threat – not even the nobles of Cyprus would commit themselves to the defence of the Holy Land without debate – and barons holding fiefs on the mainland often made their local truces with Baybars. Edward, like many other European crusaders, settled for a truce with the surrounding Muslims after an unsuccessful raid to the south. In June 1272 he survived an attempted assassination, although he remained seriously ill for some months. He left for home and succeeded to the crown of England on 22 September 1272.

One of the anomalies that Edward found hard to deal with was the amount of trade carried on between the Italian merchant communities and the enemy, for the Venetians had a profitable business in supplying Egypt with all the timber and metal it needed for armaments; and the Genoese, while trying to muscle in on that trade, specialized in providing slaves to the highest bidder. To Edward it was even more surprising that both communities held licences from the High Court of Acre which made their trade with the enemy legitimate. The commercial stakes were high, and at times the competitive Italian merchant communities came to blows both at sea and ashore. During the 1250s there had been pitched battles in the streets of Acre when both sides brought in siege machinery in what was called the ‘War of St Sabas’. This bitter struggle stemmed from Venetian and Genoese competition for the domination of the trade routes to Europe, but in Acre the barons of Outremer and the leaders of the Military Orders took sides and further divided the kingdom. The Genoese succumbed after two years, but today you can still see fortified gates at the entrances to their quarter and parts of the massive defensive wall that the Venetians erected when they took over some of the abandoned Genoese quarter.

Medieval maps show the city streets and the self-governing quarters, like the Italian communities with their great palaces and markets, together with churches and religious communities. A traveller in the thirteenth century, Willbrand of Oldenburg, left this description of Acre: ‘This town is good and strong, situated on the sea coast; so that, while it is quadrangular in shape, two of its sides, which come to an angle, are bounded and fortified by the sea; the remaining two sides are protected by good, large, deep moats, lined with stonework from the bottom. Crowned by a double-turreted wall firmly arranged in such a way that the first wall with towers, not higher than the main wall, is overlooked and protected by the second and inner wall, whose towers are high and most powerful.’ The Accursed Tower, the Tower of the English, the Gate of the Evil Step and Bloodgate have left no trace – the existing defences are nineteenth-century Ottoman – but the harbour area is revealing. In medieval times it had an international reputation ‘second only to Constantinople’, in the view of the Muslim traveller, Ibn Jubayr. It was a natural anchorage in antiquity and, standing on the sea wall of modern Acre, you can still see the outline, just beneath the waves, of a breakwater put there in ancient times.

The medieval harbour, filled by galleys and merchant vessels in the peak seasons around Easter time and in the autumn, had an inner and an outer anchorage. According to Theodorich: ‘In the inner harbour are moored ships of the city and in the outer are those of foreigners’. The inner harbour is well described by contemporary sources as having a huge iron chain slung between two towers that could close the harbour to traffic. One of those – the ‘Tower of the Flies’ – survives in part at the end of a breakwater, the foundation of which can still be seen in aerial photographs, but the focal point of the harbour is the Customs House. The fine two-storey building at the water’s edge, which has a large colonnaded courtyard, was reconstructed by the Ottomans in the nineteenth century. It was where flotillas of lighters and other small craft landed the merchandise and pilgrims from ships at anchor in the outer harbour.

For the return journey to Europe the merchants loaded the spices and other goods brought overland via Damascus by Muslim caravans. Ibn Jubayr left us this description of Acre’s customs at work: ‘We were taken to the custom house, which is a khan prepared to accommodate the caravans. Before the door are stone-benches, spread with carpets, where are the Christian clerks of the customs with their ebony ink-stands ornamented with gold. The merchants deposited their baggage there and lodge in the upper storey. The baggage of any who had no merchandise was also examined in case it contained concealed merchandise, after which the owner was permitted to go his way and seek lodging where he would.’

Acre in the central Middle Ages must have been an extraordinary place. One traveller counted thirty-eight churches, including the great Gothic church of St Andrew which mariners used as a navigation mark when approaching the coast. There were also many ecclesiastical establishments that transferred to Acre after Jerusalem was lost to Saladin in 1187, so that the streets were full of dispossessed clerics rubbing shoulders with the human dregs of medieval Europe. Acre had become an unofficial penal colony for all sorts of criminals who could escape serious prison sentences at home in return for a penitential lifetime of service in the Holy Land. For them it was business as usual among the gullible pilgrims in a city burgeoning with riches and endless opportunities for villainy. Acre’s reputation as the ‘wickedest city in the world’ was probably well earned.

Those who seek out Acre find a small, provincial fishing port, overlooked by an Ottoman town mixed with more recent buildings, back from the water. But look closely at the streets and the buildings behind the peeling paint, festoons of electric cables and modern concrete additions! Hidden behind the façade of modern Acre there are ruined towers and fragments of buildings which archaeologists, during a survey in the 1960s, realized were the remnants of the crusaders’ splendid medieval capital. In coming to the conclusion that much more of royal Acre survives than was ever thought possible, the surveyors employed a simple but effective method; they systematically measured the existing streets and buildings and compared their findings with what was shown on medieval maps. The degree of correlation was astounding. The street plan for whole areas of the town fitted almost exactly, showing that the same alignments had been followed for eight centuries.

The survey team then wanted to discover if the buildings themselves could be contemporary with the crusades as well. Investigation of the foundations and interiors of buildings revealed that many original parts of medieval Acre were intact. There were long lengths of the vaulted streets, watchtowers and gatehouses of the Pisan and Genoese and Venetian quarters, and street after street of two-storey medieval houses. The Pisan market, adjacent to the Custom House, and reached by a narrow covered street, is unchanged in its layout and essential thirteenth-century features.

The quadrangle is complete, although many of the arched openings, where the merchants stored and displayed their goods, have been bricked up. These days the market is used as a shabby, litter-strewn backyard for tenement families occupying what were once the houses of wealthy Pisan merchants.

The buildings that survive further back from the harbour were found to be even more remarkable. Away from the water the ground rises steeply, concealing the buried remains of the crusaders’ great palaces and public buildings. The ‘tell’ or mound that contains the medieval past – over which modern streets have been laid – is up to 24ft deep, and archaeologists entering an underground world, through cellars and sewers, found a series of huge sand-filled buildings of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. One of the most impressive buildings cleared during the 1950s and ’60s is the ‘Crypt of St John’, in what was once the Hospitaller quarter. This huge, groin-vaulted hall, supported by three massive drum-like central pillars, has been identified as the Hospitallers’ refectory, and its late twelfth-century dating leads historians to believe that they have discovered one of the earliest buildings to display the first flowering of Gothic architecture.

But even more exciting is the discovery of more of the Hospitaller quarter, which Eliezer Stern of the Israel Antiquities Authority began in 1990. He has unearthed a large courtyard with substantial buildings opening on to three sides. A series of vaulted halls, each 30m by 45m, was dug out of the hillside; they also found a group of eight barrel-vaulted halls which were perhaps the barracks of the knights, and, in another building, probably a dormitory opening off the central court, they discovered a latrine block on three levels. The waste was taken down through internal pipes to a sewer in the basement, which emptied into the sea. Archaeologists are still finding more of the Hospitaller Quarter underneath the modern town, and, under the flood lights, the excavation looks more like a mining operation – the town above has to be shored up as the excavation proceeds, and to hold the roof up archaeologists and engineers have devised a way that is both aesthetically pleasing and practical. The re-erected columns have been strengthened with a core of steel. The metal interior cannot be seen but it connects with a web of concrete and steel girders above which stops the modern town from falling into a medieval void. In one of the medieval halls a deeper trench revealed the remains of classical Greek buildings reminding us of the deeper antiquity of the site. Most recent excavations have made it possible to walk through a street of the crusader city – along an alley lined with blocked doorways on either side filled with rubble.

Archaeologist’s short probes have revealed coins, pottery and glass objects that survived the destruction of the city in 1291, showing for the first time the extent of the trade with the rest of the world including China. Pilgrims have also left their mark on the alley – graffiti showing heraldic symbols of some of the crusader families and sketches of the ships they sailed in to reach the Holy Land. It could be a rich source of medieval social history as families are identified by their coat of arms. When I visited the excavations in December 2009, Eliezer Stern told me that another five years of consolidation would be needed before the doorways of the houses in the street could be explored. He believes that the last ten years have ony revealed the edge of the underground city and that about 90 percent lies untouched. In the East, the barons of Outremer were as disunited as ever, and in 1276 King Hugh, who had come to the throne of Jerusalem in 1269, gave up trying to run his kingdom and retired to his other realm of Cyprus. Maria of Antioch, who had contested his right to the throne for many years, sold the Kingdom of Jerusalem, with the Pope’s approval, to Charles of Anjou, King of Sicily. His was not a consolidating influence and when Sultan Baybars died, probably of poison, after campaigning in Anatolia in 1277, his eventual successor, Qalawun, carried on with the gradual reduction of Frankish territories. The Hospitallers’ great castle at Marqab fell in 1285; in 1287 the last remaining possession of the Principality of Antioch, the port of Latakia, fell to a Muslim army, and in 1289 Tripoli met the same fate.

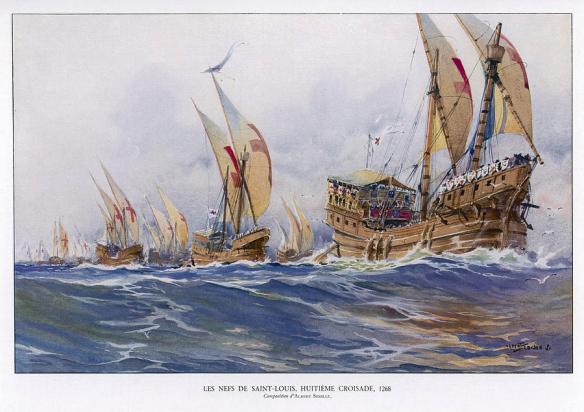

Pope Nicholas IV wrote to the kings of Europe begging for a crusade to relieve the Franks, but to no avail. An English force sailed in 1290 and it was followed by a band of peasants and townspeople from Lombardy and Tuscany; the Venetians agreed to supply twenty galleys and Aragon five, and the army was under the command of the exiled bishop of Tripoli.

But this small, ill-equipped group of saviours, which reached Acre in August 1290, turned out to be drunken and unruly. They started picking fights with anyone they thought was a Muslim on the streets on Acre and, at a time when a truce between the Mamluk Sultan Qalawun and the barons of Outremer still held, there were plenty of opportunities to confront Muslim merchants and farmers going about their business in the city.

The Tuscans and the Lombards provoked a riot and during the mêlée began killing as many Muslims as they could find. It turned into a massacre, which the sultan took as good reason for ending the fragile truce. Qalawun died before he could march on Acre but his son, al-Ashraf Khalil, went ahead with a siege which began on 5 April 1291. Ludolph of Suchem left us this impression of Sultan al-Ashraf Khalil outside Acre confronting the Christians. ‘He pitched his tents, set up sixty machines, dug many mounds beneath the city walls, and for forty days and nights, without any respite, assailed the city with fire, stones, and arrows so that [the air] seemed to be stiff with arrows. I have heard a very honourable knight say that a lance which he was about to hurl from a tower among the Saracens was all notched with arrows before it left his hand.’

King Henry of Cyprus and Jerusalem, who had been crowned in 1286, arrived with reinforcements a month after the siege had begun, but in spite of an heroic defence by the people of Acre the walls and towers were overwhelmed. Thousands of inhabitants tried to evacuate by sea; many got away, but, because there were not enough boats, large numbers were left on the quayside. One chronicler tells the story of 500 ladies of noble birth crowding around the harbour, promising sailors whatever they asked to get a place on a boat that would take them to safety. Many unscrupulous men suddenly acquired great riches but, according to Ludolph of Suchem, one sailor filled up his boat, took a load to Cyprus and, like a medieval Scarlet Pimpernel, refused payment or even offers of marriage and disappeared into history without giving his name.

Untold numbers lost their lives or were carried off into slavery, along with great swags of booty, including a gothic doorway of an Acre church, St Andrews, which now, somewhat incongruously, decorates the façade of a building in medieval Cairo. The last bastion in Acre to fall was the great Templar fortress on the shore at the south-western end of the city. The Knights agreed to surrender, then changed their minds because of the behaviour of the Muslim soldiers and fought on until the sultan’s mines toppled the huge edifice, crushing large numbers of Templars and Muslim soldiers fighting among the ruins. For the Muslims it was a profound victory of deep religious importance that was evident in the reception accorded to the victorious sultan in Damascus. Ibn Taghribirdi described an ecstatic welcome: ‘The entire city had been decorated, and sheets of satin had been laid along his triumphal path through the city leading to the viceregal palace. The regal sultan was preceded by 280 fettered prisoners. One bore a reversed Frankish banner; another carried a banner and spear from which the hair of slain comrades was suspended. Al-Ashraf was greeted by the whole population of Damascus and of the surrounding countryside lining the route: mosque officials, Sufi shaykhs, Christians, Jews, all holding candles, even through the parade took place before noon.’

On the Mediterranean coast today, a tumbled wall washed by the sea marks the site of the last heroic hours of the defence of Acre, and of Christian power in Palestine. As a poignant postscript to Acre’s violent end, a traveller is reputed to have come across some once-proud Templar Knights, thirty years after the fall of Acre, serving their Muslim masters as woodcutters by the Dead Sea.