While Louis tried to pick up the pieces of his shattered crusade in Acre, news of its defeat stirred deep emotions among the rural population in France. What happened was not unlike the reaction to the loss of Jerusalem when the Children’s Crusade had burst through the towns and hamlets of France and Germany. This time, shepherds were on the march, led by a demagogue known as the Master of Hungary who had the idea that shepherds, through their honesty and simplicity, could achieve for God what the French nobles had failed to do. The Master of Hungary was described as sixty years old and, according to one source, was a survivor of the Children’s Crusade of 1212. He began preaching soon after Easter in 1251, claiming that he had a document of authorization from the Virgin Mary.

Young shepherds and herdsmen began to follow him and, according to the Chroniques de St Denis, a crowd of 30,000 gathered over eight days; together they marched to Amiens where the inhabitants were fascinated by the Master of Hungary. ‘He came before them with a great beard, also as if he were a man of penitence; and he had a pale and thin face… some knelt before him, as if he were a saint and gave him whatever he wished to demand.’ According to the English chronicler, Matthew Paris, who recounts that he heard the story from an English monk held prisoner by the shepherds for eight days, they carried standards depicting the lamb and the cross: ‘the lamb being a sign of humility and innocence, the standard with the cross a sign of victory’. But as well as the banners, including the one showing the Virgin Mary who was supposed to have appeared before the march, they were also armed with swords, axes and knives.

In Paris they received royal patronage. Queen Blanche, Louis’s mother, and regent while he was in the East, gave the Master of Hungary an audience and showered him with great gifts. The St Denis chronicler thought that ‘she hoped that they would bring some aid to King Louis, her son, who still remained in Outremer’. Queen Blanche was soon to regret her endorsement of this enterprise. In Paris, the shepherds began to run amok and the Church became a target of their violence; they were reported to have slaughtered the clergy and desecrated churches; there was trouble all the way through France, but in Orleans Matthew Paris wrote that people turned out to hear the Master of Hungary preach, ‘in an infinite multitude’. The bishop tried to stop the clergy from attending but when a scholar from the university began to heckle, a riot broke out. Twenty-five clerics were killed, says Matthew, ‘without [counting] those wounded and injured in various ways’. The Jews suffered as well and it was not long before Queen Blanche was forced to outlaw the shepherds.

Some of their followers are said to have reached Aigues-Mortes where they expected a ship to take them to the East, but most dispersed and made their way home. There is no doubt that the shepherds received a bad press because, as Dr Malcolm Barber of the University of Reading points out, all the sources for the story of the crusade were clerics who were not anxious to admit to the anti-clerical feeling among many people at that time. Indeed, the criticism reached a shrill pitch when the Master of Hungary was accused by one writer of having been in league with the Muslims and interested only in selling French boys as slaves. In spite of the trouble the shepherds caused, townspeople did open their gates to them and it can be argued that, while the crusade did get out of hand, it contained many familiar elements of sincere crusading.

Matthew Paris, continuing his story, says that one group of shepherds landed at the port of Shoreham in Sussex. But when their leader began preaching, his audience turned on him and, ‘in fleeing into a certain wood [he] was quickly captured and not only dismembered, but cut into tiny pieces, his cadaver being left exposed as food for the ravens’. The Warden of the Cinque Ports was under instructions to expel any shepherds who were trying to preach their crusade, but as Matthew says, some of those would-be crusaders took the Cross, ‘from the hands of good men’, and set off to serve King Louis in the Holy Land.

Louis’s vision for the protection of the Frankish kingdom in Palestine extended beyond the rebuilt battlements of Caesarea and Acre. He sent envoys to the Mongols and those envoys ended up at the court of the Mongol emperor Mongka at Karakorum in central Asia – a journey that took William of Rubruck the best part of a year. He arrived bearing greetings from Louis in 1254 at a court which had become the centre of a vast empire that stretched from the South China Sea to the shores of the Mediterranean.

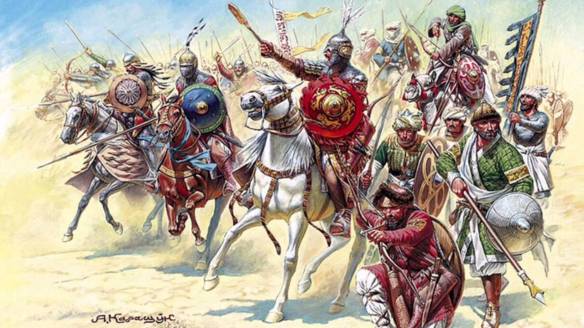

The Mongol expansion had started when a group of Turkish and Turko-Mongol tribes in the north-west of China were welded together under the leadership of Genghis Khan. In 1206 he set out to conquer the world and very nearly did; he took northern China, including Peking, during 1211-12, and by 1221 Mongol armies were raiding along the banks of the Indus River. Genghis Khan’s sons, by the 1240s, had overrun central Russia, the Ukraine, Korea, Poland, Hungary, Iran and Asia Minor. Their empire was built on the efforts of ruthless and courageous nomadic warriors who did not surrender or take any prisoners. John of Pian del Carpini, an envoy of Pope Innocent IV who visited the Great Khan in 1246, said that their army was organized in units of ten, each with its own captain. ‘At the head of ten captains of a hundred is placed a soldier known as captain of a thousand, and over ten captains of a thousand is one man, and the word they used for this number is darkness.’

The Mongols seem to have had unlimited mounted warriors who could tirelessly travel for days across the steppes of central Asia, each man carrying ‘two or three bows, three large quivers full of arrows and an axe and ropes for hauling siege engines of war’. These tough nomads, according to the Pope’s envoy, observed a strict moral code and dealt abruptly with thieves and adulterers by putting them to death. On a long campaign the troops would eat anything and, in extremis, would select other members of the army to be slaughtered and eaten. ‘When they are going to make war, they send ahead an advance guard and these carry with them nothing but their tents, horses, and arms. They seize no plunder, burn no houses and slaughter no animals; they only wound and kill men.’ The well-disciplined military machine provided a following wave of troops to take care of the plunder. As they moved across the vast plains of Asia, pastures that suited so well their sturdy little horses and flocks of animals, the warriors took their families with them. ‘Their women make everything, leather garments, tunics, shoes, leggings… they also drive the carts and repair them, they load camels, and in all their tasks they are very swift and energetic. All the women wear breeches and some shoot like the men.’

These people of the central Asian steppes were for the most part pagan but there was an influential minority of Nestorian Christians – a heretical sect which broke from the early Church and expanded eastwards in the fifth century. The Mongol emperor’s mother had been a devout Christian and his principal wife and many of his other wives were also adherents to the faith. The emperor himself attended Buddhist, Muslim and Christian services, declaring that there was only one god, who could be worshipped anywhere.

King Louis’s ambassador waited his turn for an audience with the Great Khan along with embassies from the Caliph of Baghdad, princes from Russia, the Seljuk sultan from Asia Minor and the King of Delhi; William of Rubruck even found a man called Basil, the son of an Englishman, living in the imperial capital, but while the emperor was well-disposed towards the Christians and their struggle with the Saracens, he viewed the world quite differently from King Louis in Acre. Like many oriental rulers before and after him, he regarded the potentates of the West as only tinpot kings on the periphery of the civilized world and, as such, to be treated as vassals. Louis’s ambassador, the second he had sent to the Mongol court since the start of his crusade, came back with nothing that was acceptable in western terms, and noted, as he travelled across half the world on an important trade route, that he made the journey safely and in comparative comfort under the protection of the Mongol administration all the way.

The Armenian King Hethoum also visited Karakorum in 1254, and, mindful of the Mongol control of Anatolia, paid homage to the Great Khan. In return for military assistance against the Muslims, the Mongol emperor offered to restore Jerusalem to the Christians – but under his imperial auspices. Bohemond of Antioch, King Hethoum’s son-in-law, also agreed to support the Mongolian advance into Syria, but the Franks of Palestine did not trust the Mongols and were probably far more realistic. In January 1256 the Mongol army began to move west; it crossed the River Oxus under the command of Mongka’s brother, Hulagu. Engineers went ahead of the army preparing roads and bridges, and siege machinery was brought thousands of miles from China. The Assassin headquarters at Alamut in Iran fell and Hulagu then advanced on Baghdad in spite of the 120,000 cavalry that the caliph was able to put into the field. On 15 February 1258 Hulagu triumphantly rode through the city that had been the seat of the Abbasid Caliphs for five centuries; and in the sack that followed, the Mongols slew 80,000 of Baghdad’s citizens – among them the Caliph Al-Mustasim himself. Baghdad’s Christians, however, who were all sheltering in the churches, were spared.

The cities of upper Mesopotamia were the next to be overrun, and in the autumn of 1259 the Mongol army crossed the Euphrates and was soon at the gates of Aleppo. When Hulagu arrived at the frontier of Antioch, Hethoum, King of Armenia, and Bohemond, Prince of Antioch, rode out to the Mongol camp to pay homage. The two Christian rulers were then offered a number of captured castles and when the Mongol army moved against Damascus its Christian general, Kitbuqa, had by his side the two Christian rulers from Cilicia and Antioch.

At this point, the Christians in Palestine decided that the Mongols were a threat and not potential allies. They applied for help to Louis IX’s brother, Charles of Anjou. He was becoming embroiled in the Pope’s political crusade against the Hohenstaufen and the appeal came to nothing, but just as the Mongols were laying plans to take control of Egypt, the Great Khan, Mongka, died while campaigning in China in August 1259. Inevitably, his brother, Hulagu, turned his attention from the Near East to Mongolia itself, where various members of the imperial family were jockeying for the right of succession. Hulagu moved troops to his eastern frontier ready to intervene if necessary, while his general Kitbuqa was left to govern Syria with a much-reduced army.

The Mamluks were ready to exploit this weakness. The leader of a Mongol embassy which arrived in Cairo to demand the sultan’s submission was executed and an army led by the Mamluk Sultan Qutuz prepared to march against the Mongols in Syria. Qutuz crossed the border on 26 July 1260 and took the small Mongol garrison at Gaza. He then wanted to cross the Frankish territory to engage the Mongol army in northern Palestine and Syria and sent an Egyptian embassy to Acre seeking permission to cross Christian-held lands. The barons of Acre now decided to help the Egyptians and agreed to re-victual the Egyptian army and grant it safe conduct through Christian territory, although a military alliance was rejected. While the Mamluks camped in the orchards outside Acre, news was received that the Mongol army had crossed the Jordan and entered Galilee.

The Mamluk and Mongol forces met at Ain Jalut, the Pools of Goliath, on 3 September 1260. The Mongols advanced into the hills in pursuit of Baybars’s forces, unaware that the main Mamluk army was hidden nearby; Qutuz then sprang the trap and with his superior numbers surrounded the Mongols and tore their army to shreds. That battle brought Mongol expansion in Syria and Palestine to a full stop, although it is possible that they had reached the limit of their advance anyway, but it also marked a long period of attrition and decline for the Frankish states.

The Mamluks’ front line advanced to the Euphrates river and Mongol attacks into northern Syria brought Egyptian reinforcements hurrying north through the Palestinian corridor. When the Mongols withdrew or their armies simply did not materialize, Muslim commanders would unleash their troops on Christian towns and castles on the long march back to the Nile. Under Qutuz’s murderer and successor, Baybars, the systematic reduction of the Latin settlements got under way. In 1265 Caesarea, Haifa and Arsuf fell to him; the great Templar castle of Safad was taken in 1266. Jaffa, Beaufort and Antioch fell in 1268 and, in 1271, Crac des Chevaliers and Montfort. The Mamluk campaigns were characterized by savagery and slaughter; when Baybars led a raid on Acre in May 1267 he ravaged the nearby countryside and decapitated all the inhabitants he could find. Frankish ambassadors sent to Safad to negotiate a truce with him reported that the castle was surrounded with the severed heads of Christian prisoners.

There can be no doubt that the Holy Land was never far from King Louis’s thoughts in France. He poured money into the defence of the Frankish East year after year – an average of 4,000 livres tournois annually between 1254 and 1270 – and he hankered after another big crusade to redeem his reputation and clear his conscience. The papacy, however, was preoccupied with political crusades in Italy that sought to extinguish forever the influence of Frederick II. It was also to be a period of great change in other parts of the commonwealth of Christendom. Latin Constantinople fell in 1261 to the Byzantine emperor Michael VIII; the French and Venetians still held southern Greece and the islands of the Aegean, but naval war between the Italian maritime states was taking a heavy toll on Venetian and Genoese shipping. Louis’s brother, Charles of Anjou, not only won Sicily for the Pope and a crown for himself by defeating Frederick’s bastard son, Manfred, in 1266, but also became overlord of most of the remaining Latin settlements in Greece.

As the threat from Frederick’s heirs receded – Conrad was finally captured and executed by Charles in October 1268 – Louis’s idea for another crusade was promoted actively by the papacy. In 1267 Louis took the Cross, but he must have been disappointed with the poor response from those around him – for example John of Joinville, the historian of Louis’s first crusade, would not go – and Louis sailed from Aigues-Mortes in the summer of 1270 with not more than 10,000 men. Among his retinue were his three sons, his son-in-law, King Thibald of Navarre, and the counts of Artois, Brittany, La Marche, Saint Pol and Soissons. Many of the nobles were sons of crusaders who had sailed with him to the Nile twenty-two years before. But Louis’s flotilla did not go to the East; it headed instead for Tunis on the North African coast.’