The earliest Roman ventures across the Adriatic had occurred before the Second Punic War. The First and Second Illyrian Wars (229–228 and 221–219 BC) had been fought ostensibly to suppress piracy, but the interference with a minor state in Macedonia’s backyard had alarmed King Philip V sufficiently for him to form an alliance with Hannibal in 215 BC. The First Macedonian War (215–205 BC) proved a damp squib, however: Philip never sent support to Hannibal in Italy, and the Romans left their Aetolian allies to fight alone in Greece. But this reflected not pusillanimity on Philip’s part so much as his preoccupation with the Aegean – where his war with Pergamum and Rhodes provided a pretext for Roman intervention against him in 200 BC. The alliance with Hannibal, and his wars against fellow Greeks, including Roman allies, made it easy enough to portray Philip’s Macedonia as a dangerous ‘rogue state’.

In fact, Philip was no threat to Roman interests. The very fact that he did not send troops to Italy in the wake of Cannae is proof enough of that; Philip’s fighting front was to the south and the south-east, not towards the Adriatic. The Roman decision to back Pergamum and Rhodes and intervene in an eastern war was an act of aggression. Significantly, when the consul to whom responsibility for Macedonia had been given proposed a declaration of war, the Assembly of the Centuries turned it down. When he next summoned the assembly, he deployed a new concept: that of pre-emptive aggression against a would-be (and in fact imaginary) enemy. The decision was not ‘whether you will choose war or peace; for Philip will not leave the choice open to you, seeing that he is actively preparing for unlimited hostilities on land and sea. What you are asked to decide is whether you will transport legions to Macedonia or allow the enemy into Italy; and the difference this makes is a matter of your own experience in the recent Punic Wars … It took Hannibal four months to reach Italy from Saguntum; but Philip, if we let him, will arrive four days after he sets sail from Corinth.’ The Assembly now voted for war. A real hatred of the draft had been overcome by an invented fear of invasion. For invented it was, the speciousness of the consul’s argument apparent from the most superficial review of the events of the Second Macedonian War (200–196 BC). The largest Roman army sent to Greece was only 30,000 strong – a mere 2.5 per cent of Rome’s total military manpower, or 7 per cent of her maximum mobilized strength in the Second Punic War. Yet this small army was sufficient to bring Macedonia to defeat – a defeat Philip anticipated judging by his interim peace offers and initial avoidance of battle. Hannibal, by contrast, had destroyed a Roman army of 80,000 – and still lost the war. These simple calculations demonstrate how suicidal a Macedonian invasion of Italy would in reality have been: doubly so, since not only would the invaders have been crushed, but Philip’s kingdom would meantime have been overrun by his enemies in Greece.

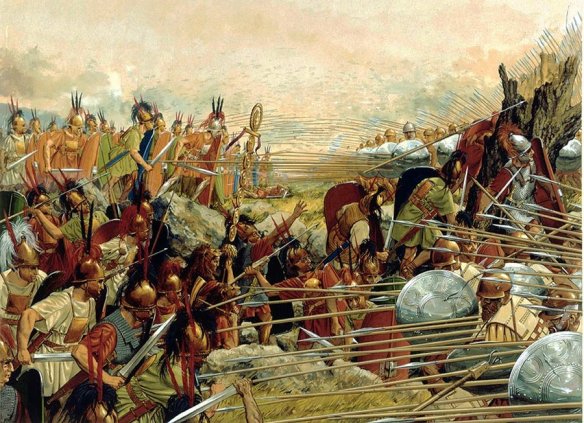

The first two years of the war were inconclusive, but in the spring of 197 BC Titus Quinctius Flamininus invaded Thessaly, and Philip, finally resolved to risk battle rather than prolong a war of attrition he knew he could not win, marched towards him with 25,000 men. The ground was unsuitable for battle where the armies first met, and both withdrew along parallel routes separated by low hills, each soon unaware of the other’s progress. A messy encounter battle then developed unexpectedly at Cynoscephalae when Macedonian and Roman detachments clashed in the mist on the heights overlooking a pass between the main armies. As more units were drawn into the fight for the high ground, a general engagement began. The Macedonian right reached the top of the pass before the Romans. When Philip saw this, he ordered the right phalanx to close up into a deep formation, increasing its shock power, and then to charge. Flamininus, seeing the desperate struggle that had begun on the Roman left, ordered in turn an attack by his right, which struck the left phalanx before it was properly deployed and routed it. The battle divided into separate halves, with the Macedonian right pushing down one slope, the Roman right down the other, such that a wide gap opened. At this point, a Roman military tribune seized the initiative. Taking the 20 maniples of triarii forming the rear line of the legions on the right, he reformed them and charged into the rear of the phalanx attacking the Roman left. The effect was devastating. The right phalanx was also routed. The battle had been hard-fought but decisive. About 8,000 Macedonians had been killed and 5,000 captured for a loss of 700 Romans. Philip V’s only army had been destroyed and he was compelled to make peace.

The battle of Cynoscephalae in 197BC was also fought up and over high ground which Plutarch describes as ‘the sharp tops of hills lying close beside each other’. Polybius calls the ridge ‘rough, precipitous and of considerable height’. Pietrykowski calls the ridge upon which the battle was fought ‘a true liability’ to the ‘ponderous phalanx’. Morgan, on the other hand, points out that the terrain does not seem to have been a deciding factor in the outcome of the battle.⁶⁰ Both of these claims seem to be only partially correct as, depending upon the exact nature of the ground on certain parts of the ridge, the phalanx was either hindered (which ultimately led to its defeat) or not.

The Macedonian army of Philip V, and the Roman army of Titus Flaminius, were both encamped on either side of the ridge at Cynoscephalae. Philip is said to have considered the ground unsuitable and unfavourable for a major engagement but, following initial contact and skirmishing between advance units from both sides, and the receipt of favourable reports from the ridge above which stated that the Romans were in retreat, Philip began to commit more troops to the action including elements of his pike-phalanx. Units of Philip’s right-wing phalanx surmounted the ridge at a run: a manoeuvre which must have necessitated their pikes being held vertically. Livy says that, once in position and arranged in double depth, the phalangites were ordered to drop their pikes and fight with swords because the length of the weapons was a hindrance. Both Polybius and Plutarch, on the other hand, state that the phalanx engaged with its pikes lowered. Indeed, there are several reasons why Livy’s account should be considered incorrect in this matter. Firstly, Livy later states that the phalanx was unable to turn about to face an attack from the rear. While this is true of a phalanx with its pikes lowered, it can be easily accomplished by one just fighting with swords. This suggests that the Macedonians were using the sarissa. Secondly, Livy also states that, at the end of the battle, parts of the phalanx signalled their surrender by raising their pikes. It is unlikely that the members of the phalanx had put away their swords, picked up their pikes – which would have been somewhere uphill behind them as the sources all state that the Macedonian right wing pushed the Romans down the slope – and then used them to signal their surrender. It is more likely that the phalanx had been using their pikes all along.

The phalanx units on the Macedonian right wing effectively engaged the Romans using the advantages of the high ground to their fullest. Plutarch states that the Romans facing these units could not withstand their attack. It was a different story on the Macedonian left, however, and it was in this quarter that the nature of the terrain may have hampered (and eventually defeated) the pike-phalanx. Livy says that additional pike units were brought up in column – a formation he says is better suited to a march than a battle – rather than in extended line. The ground here may have been more broken than on the right and this caused large gaps to open in the phalanx as it deployed: gaps which the more mobile Roman maniples were able to exploit to defeat the Macedonian left and then swing around to attack the remaining units on the Macedonian right. Polybius states that this fracture of the phalanx on the left was due to some units already being engaged, others only just making the top of the ridge, while others were in position but were not advancing down the hill. Interestingly, none of these factors have much to do with the nature of the terrain itself and, as such, the extent to which the ground caused the fragmentation of the Macedonian line at Cynoscephalae cannot be conclusively determined. However, it seems clear that it is not the incline of the battlefield which is a hindrance to the operation of the pike-phalanx, but whether or not the line can be maintained on the terrain that the battle is fought upon. This again goes against Polybius’ claim that the phalanx could only operate on ‘flat’ ground.

Polybius was fascinated by the clash between phalanx and legion. The whole fate of the Hellenistic world – his world – had seemed to hinge on it. The outcome appeared paradoxical, for the compact formation and projecting pikes of the phalanx meant that in close-quarters combat each Roman legionary, fighting in a much more open formation, faced no less than ten spear-points. ‘What is the factor which enables the Romans to win the battle and causes those who use the phalanx to fail? The answer is that in war the times and places for action are unlimited, whereas the phalanx requires one time and one type of ground only in order to produce its peculiar effect.’ Broken ground disordered the phalanx, creating fatal gaps in the hedge of pikes. To be effective, it had to operate in a large block, making it slow, cumbersome and unresponsive to a changing battlefield situation. The Roman formation, by contrast, was flexible and mobile. While part could pin a phalanx frontally, other parts could manoeuvre to attack flank and rear. ‘Every Roman soldier, once he is armed and goes into action, can adapt himself equally well to any place or time and meet an attack from any quarter. He is likewise equally well-prepared and needs to make no change whether he has to fight with the main body or with a detachment, in maniples or singly.’ Cynoscephalae illustrated these dictums. It showed that the legions were coming of age, that a complex evolution of the Roman military tradition under Etruscan, Greek, Samnite, Gaulish, Punic and Spanish influence was now producing the finest fighting formations in the ancient world.