Towards the end of his life, the slavishly loyal Molotov admitted that his boss made one big mistake. Stalin had got almost everything right in decades of power, he said, except with regard to Turkey in 1946. There he had miscalculated badly, and the Soviets and Americans nearly stumbled into a war neither of them wanted. It was avoided only by the alert action of a British spy.

During August and September, the Paris Peace Conference became increasingly ill-tempered. The delegates were tetchy. At one of their first meetings Ernest Bevin had likened Molotov to Hitler; the Soviet luminary (who had actually met Hitler) first looked shocked, then sneered and turned his back on the British Foreign Secretary. Bevin apologised but the encounter festered. Bevin had loathed communists since they had tried to penetrate his beloved Transport and General Workers’ Union and some sections of the Labour Party in the Twenties and Thirties, and seldom hid his feelings. In Paris he said, ‘Molotov is like a communist in a local Labour Party. Treat him badly and he makes the most of his grievance and if you treat him well he only puts his price up and abuses you afterwards.’

Behind the scenes, the Soviets were trying to bully the Turkish Government into granting them military bases on the Bosphorus – a key Russian objective since Tsarist times – and free access for warships through the Hellespont. Immediately after the war, Stalin had demanded joint ownership with the Turks of the small towns of Kars and Ardahan in north-eastern Turkey. They had been conquered by Russia in the reign of Catherine the Great, but were ceded back to Turkey by Lenin in 1921, when the Bolsheviks were preoccupied with the Russian Civil War. The Turks refused and at Potsdam the Americans and the British had backed them. The Soviets could have access through the Straits but no bases.

Stalin would not give up. There were 200,000 Soviet troops in Bulgaria and 75,000 in Romania. He calculated that if he exerted enough pressure on the Turks they would give in to Soviet demands and the Western Allies would accept it as a fait accompli.

Molotov for once disagreed with the Vozhd. ‘The West won’t accept it. It is a step too far,’ he told Stalin; as he said later, ‘It was always an ill-timed and unrealistic thing . . . but Stalin insisted and [ordered me] to go ahead and push for joint ownership.’

The Turks approached the Americans for help. Convinced that the Soviets were preparing to invade Turkey, Truman saw this as a major test of his tougher ‘containment’ policy. In the Oval office on the morning of Thursday 15 August, he met the Joint Chiefs of Staff, the Director of Central Intelligence, and Dean Acheson, standing in for the Secretary of State, Byrnes, who was in Paris. The generals and the intelligence chief reported that there was no obvious sign of Soviet troop movements in the Balkans, but this was far more a political than a military matter. Acheson had not urged a strong line in the Iran crisis six months earlier; instead, he had recommended leaving the Russians a graceful exit route. This time, however, he was unequivocal. ‘It is a vital American interest to deter the Soviets,’ he told the President. ‘And it can only be done if the Soviets are persuaded that the United States is prepared to meet their aggression with force of arms.’

Truman agreed almost at once. He ordered the immediate dispatch of a fleet to the Mediterranean. The Pentagon had the previous year begun work on Operation Pincher, a plan for war in the Middle East, but it had been left in abeyance. The President wanted the plan looked at carefully once again.

He asked Acheson to approach the British and ask them to allow American B-29s, armed with atom bombs, to use bases in England. He also said he would pursue Acheson’s policy ‘to the end’. Acheson said later that Truman had made his decisions so quickly that one of the generals asked him whether he entirely understood the implications. Truman reached into his desk, pulled out a large and well-worn wall map of the world, and began to lecture the room about the historic importance of the Middle East from ancient times. ‘We might as well find out if the Russians are bent on world conquest now as in five or ten years,’ he declared.

Four days later, 19 August, the State Department told Molotov emphatically that the ‘defence of the Straits is a matter best left to Turkey’. Soviet ships could pass through peacefully, but if there was any threat or attack intended to secure Soviet bases in Turkey it would be ‘subject to UN Security Council action’. The implication was that the US would go to Turkey’s defence.

Tension was increased the same day when the US heard that the Yugoslavs had shot down an unarmed US Army C-47 transport plane, killing its five-man crew. The plane was just two miles into Yugoslavian air space and the attack came without warning. It was coincidence, entirely unplanned, and had nothing to do with the Russians, but the President and the State Department were sceptical. Many in the administration saw Tito as a stalking horse for Stalin and did not believe rumours of an imminent split in the communist ‘camp’. Immediately the news of the downed plane came through, Eisenhower, Chairman of the Joint Chiefs, cautioned against over-reacting. It wasn’t a crisis, he said. He told the Defense Department he didn’t think that the shooting down of a transport plane was a cause for war.

Later that night, Acheson summoned the new British Ambassador in Washington, the recently ennobled Lord Inverchapel – who, as Sir Archibald Clark Kerr, had been Ambassador to Moscow until a few weeks previously – to the State Department. He reported Truman’s comment that he would see the matter through ‘to the end.’ The Ambassador asked if the US was prepared to go to war. Acheson looked grave and replied that, ‘The President fully realised the seriousness of the issue and was prepared to act accordingly.’

In Washington they waited for the next step. Molotov explained, ‘It is good we retreated in time or . . . there would have been joint aggression against us.’ The Soviets climbed down two days later and withdrew their demands for bases. Molotov said they had ‘over-reached’ and intriguingly added, ‘Intelligence may have prevented the outbreak of war.’

It was in fact the Soviet agent Donald Maclean, part of the Cambridge spy ring, who had prevented it. Maclean was then First Secretary at the British Embassy in Washington. He knew about the conversation between his boss, Lord Inverchapel, and Acheson, and read the cable the Ambassador had sent back to London highlighting Truman’s comment that he would see the matter ‘through to the end’. He urgently passed the information to Moscow.

Stalin had never intended to provoke a war. As Molotov said, he was ‘probing’ to see exactly how far the West would go, in line with Lenin’s dictum: ‘You probe with bayonets. When you feel soft flesh, push further. If you meet resistance, feel steel, you withdraw and think again.’ Now Stalin had a better understanding of the Americans – or thought he had.

The crisis did not change Molotov’s view of spies. He relied on them extensively. As one KGB agent who was seconded from ‘the organs’ to work with him recalled, ‘We were stretched to the limit with the demands he made . . . Molotov flew into rages when he felt he was not sufficiently informed. “Why”, he once roared, “why are there no documents?”’

Molotov distrusted everybody; it was a cast of mind among the Soviet chieftains. But he reserved special suspicion for spies. ‘One cannot rely on intelligence officers. One can listen to them, but it is necessary to check up on them. Intelligence officers can lead you to a very dangerous position . . . there are . . . [among them] many provocateurs here there and everywhere.’

President Truman saw the Turkey crisis as a bloodless victory, a vindication of the policy of ‘containment’. The Russians perceived it differently – they were never intending to attack the Turks anyway. The end result, though, was that Stalin’s ‘probe’ into Turkey used up much of his political capital in the US and in Europe. He was never given the benefit of the doubt again; there would soon be American military bases in Turkey, right along the USSR’s southern border – and the hand of cold warriors in Washington who were recommending a firm hand against the Russians was strengthened.

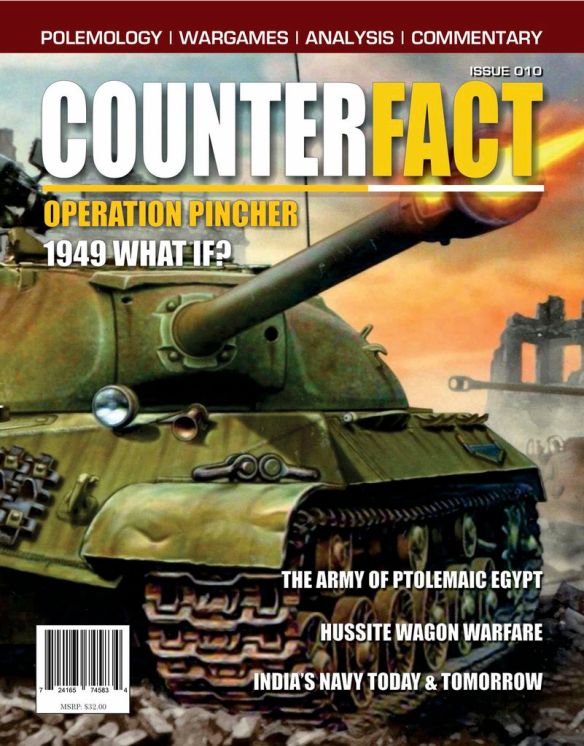

Operation Pincher

Regardless of any protests in the West, Stalin’s suppression of Eastern Europe continued apace. In March 1946 alone the Soviet Ministry of the Interior recorded that ‘8,360 bandits were liquidated’ in the Ukraine, while in the Baltic Soviet Socialist Republic (SSR) states of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia nearly 100,000 people were deported to gulags ‘forever’. Even as the packed cattle trucks of ‘bandits, nationalists and others’ trundled eastwards, Stalin launched his own verbal repost to Churchill’s Missouri speech, denouncing him as ‘a firebrand of war’. But Churchill’s views were no longer seen by the US as either extreme or as an impediment to better relations with Stalin. Just days before Churchill had delivered his Fulton speech, the US JWPC had finalised their Operation Pincher war plans. US policy was turning full circle in its attitude to the Soviet Union:

It is wise to emphasise the importance of being so prepared militarily and of showing such firmness and resolution that the Soviet Union will not, through miscalculation of American intentions, push to the point that results in war.

The US draft plan for their own Unthinkable war estimated that in the spring of 1946 the Soviets had fifty-one divisions in Germany and Austria, fifty divisions in the near or Middle East and twenty divisions in Hungary and Yugoslavia. This force of 121 divisions was supported by a central reserve of 152 divisions in the homeland, and a total of 87 divisions of pro-Soviet forces within the satellite states of Eastern Europe. A Soviet attack would most likely sweep across Western Europe and seize the channel ports and the Low Countries in little more than a month. Simultaneous attacks would be launched into Italy as well as the Middle East. In the midst of such overwhelming force (again, an estimate of three to one in favour of Soviet infantry), it was recommended that US troops would retreat into Spain or Italy to avoid being decimated by the Red Army on the continent. It was conceivable that the Red Army would even carry the invasion into Spain in an attempt to block the western Mediterranean, in which case US forces would swiftly withdraw and retreat to Britain. While Britain was considered a valuable base, Germany, Austria, France and the Low Countries would be sacrificed. Retreating Allied forces would also move across to the Middle East to bolster defences around the vital Suez Canal Zone. It was no surprise that the US chiefs of staff now accepted that an essential object of Stalinist policy was to ‘dominate the world’.

There would be a fight-back by the West, of course, but not until the Red Army had swept through Western Europe, the Balkans, Turkey and Iran; in the Far East, South Korea and Manchuria would also fall. Although Pincher did not go into further detail, the US and her Allies would launch devastating air attacks from remaining bases in Britain, Egypt and India, no doubt deploying their growing stock of atomic bombs, though the use of such weapons was still not seen as a ‘war winner’. Meanwhile the US Navy would seek to blockade the Soviet Union and destroy her naval fleets, as attempts were eventually made to recover Western Europe by a southerly thrust via the Mediterranean.

One old festering wound in Europe that looked like it could precipitate Operation Pincher was the dispute between Tito and the West over the Venezia Giulia region. It was also this scare that brought together the US and British Joint Chiefs of Staff for their first planning sessions for a Third World War. The first British Unthinkable plan, involving the attack on Soviet forces on 1 July 1945, had not been discussed beyond the tight circle of the prime minister, his Joint Chiefs and their Joint Planners. Similarly, the highly sensitive US Pincher plan was initially confined to the US Joint Chiefs, their Joint Planners and the commander-in-chief. But on 30 August 1946 Field Marshal Henry ‘Jumbo’ Maitland Wilson, representing the British Joint Chiefs, attended a lunch with his American counterparts. Reporting back to his JCS committee, Wilson was able to reassure them that at least both sets of chiefs were alert to the risk of an armed clash in Venezia Giulia, which could pull in both power blocs, whether they wanted war or not. There was agreement that in the event of a conflict in the Venezia region it was pointless having a plan for large reinforcements to be sent into the territory, since the fight would swiftly spread into central Europe. Poland, no longer seen as the tripwire by late 1946, would nevertheless find herself at the very centre of military activity.

Ironically, the US chiefs were now discussing all the scenarios that Churchill had foreseen 18 months before, when formulating his plan for Unthinkable. President Truman had even appointed a Special Counsel, Clark Clifford, to report on the growing Soviet menace, concluding that Stalin believed ‘a prolonged peace’ between the Marxist and capitalist societies was impossible and the only outcome was war. At a top-level meeting between the US and Britain, even the new US chief of staff, General Eisenhower, was talking the Unthinkable talk of establishing Allied ‘bridgeheads’ in Europe. In the face of any Soviet onslaught he advocated withdrawing forces to bridgeheads in the Low Countries. As Churchill had earlier recommended, this would deny the enemy the use of bases from which to launch rocket attacks at Britain, as well as offering the Allies a short line of communication back to Britain. The UK would be of huge strategic value for the Allied air forces, though the Americans noted that longer airstrips would be required in British bases to enable more B–29 squadrons to be accommodated. The Naval representative also argued for a reoccupation of Iceland to broaden the reach of naval forces.

So, with a consensus reached, the meeting broke up, but not before it was agreed that the utmost secrecy should be imposed on the Combined Joint Chiefs of Staff outline plan, and that no one beyond the level of the chiefs and their immediate planners should be allowed access. The US chiefs were most keen to drive on and agree a command organisation for the US and Britain in the event of Soviet aggression, which they saw as ‘imminent’. However, it was not long before other senior British commanders became involved in the plans. On 16 September Field Marshal Montgomery, supposedly on a private visit to the United States, met with General Eisenhower and President Truman to discuss the war plan options for the West. Cabling Prime Minister Attlee to advise him of developments, Montgomery referred to the highly sensitive plan and stressed it was ‘Personal and Eyes only for PM’. ‘So far as I am aware, no (repeat) no one here knows anything about matter.’ Montgomery was keen to add, ‘all agree that secrecy is vital.’ To cover their trips to meet US Joint Planning Staff, the British planners used the excuse of researching for a ‘report on the strategical lessons of the recent war’. There was even concern within the British camp that the amply proportioned ‘Jumbo’ Wilson might have presented a large silhouette on board the yacht where he met with US chiefs. Furthermore, it was questioned whether British planners should wear ‘uniform or mufti’ when meeting with their American counterparts. Fortunately, the idea of ‘cocktail parties’ for visiting teams was hastily dispensed with.

Yet it seemed that the tight security in the US was now unravelling. The British were horrified to learn that the secretaries to the US War Department and Navy Department were also aware of the plan and it was only a matter of time before operatives in the US State Department heard of the details. British security operatives may well have been aware of the leaks to the Soviets from within the State Department and feared the worst. Attlee certainly did. Confiding to Field Marshal Wilson, he stated ‘the issues now raised are of the utmost importance and potential value, but any leakage would have the gravest consequences.’

During October 1946 the Canadian war planners were also introduced to the operation and a representative met with British and US planners for further meetings in London. Discussions included the intended bridgeheads and the capacity of Naval forces to evacuate US and British troops from mainland Europe, should the Red Army advance to the West. There was also the pressing problem of renewed Soviet threats to Greece and Turkey, as well as the issue of ‘standardisation’ of weapons and equipment between the US, Britain and Canada.

Operation Pincher went through a number of modifications during the summer of 1946, and the US Joint Planners ensured that it remained relevant, but it still excluded specific reference to the use of atomic bombs by the strategic bomber force. As with Unthinkable the planners made little attempt to project beyond the initial stages of a conflict, since there were just too many variables. One of the constant worries remained the issue of demobilisation. For with peace came a great desire for ‘bringing the boys home’ as soon as possible and for reducing the huge cost of a vast army. Consequently, by June 1946 the US armed forces, which had numbered more than 12 million at the end of the war, were reduced to fewer than 3 million. Secretary of State James Byrnes was frustrated with the whole process, ‘The people who yelled loudest for me to adopt a firm attitude towards Russia,’ he moaned, ‘then yelled even louder for the rapid demobilisation of the Army.’ So formidable was the strength of Soviet armour and infantry that once US troop reductions were underway, the planners concluded that Allied land forces would not be strong enough to drive into the Soviet interior for at least three years. Allied air power offered the only hope of victory, by employing massive strikes against ‘the industrial heart of Russia’.

It was unrealistic to believe that the Soviet Union could be threatened with oblivion in 1946. Even by the autumn of that year the US only possessed nine atomic bombs. There were two Mark III Fat Boys earmarked for testing off the US mainland, and seven Mark IIIs were held in secure housings on the mainland. They could only be delivered to the Soviet Union by the Silver Plate B–29, suitably modified to hold the weapon in place, but there was a lack of properly trained aircrews, as well as bomb assembly teams. Furthermore, scientists were returning to civilian life and the production of both uranium and plutonium was falling. However, production would be dramatically increased in the next few years, so that by the time of the first Soviet atomic test in 1949, the US would have a stockpile of some 400 atomic bombs. Despite the comfort of atomic superiority, senior commanders in the West were in no doubt about the consequences of an imminent world war. ‘My part in the next war,’ wrote Sir Arthur ‘Bomber’ Harris, ‘will be to be destroyed by it.’

While Britain and the US faced up to the Soviet Union, Poland, as a cause, had slipped off the list of priorities. During Christmas Eve 1946 the ‘Polish Sixteen’, who had been the hope of a future liberated Poland, were languishing in various Soviet prisons. One of the most prominent leaders, General Okulicki, passed his last hours in Moscow’s Butyrka Prison. His disappearance, together with other leading members of the Polish underground, in April 1945, had done much to increase the climate of fear surrounding Soviet intentions. He was either murdered by the NKVD or died as a result of his hunger strike; it has been estimated that between 1944 and 1947 some 50,000 Poles, including many members of the AK, were deported to the Soviet gulags. In the spring of 1946 the US Joint Chiefs declared that the Soviet Union was giving the highest priority to ‘building up their war potential and that of their satellites so as to be able to defeat the Western democracies’. To combat Soviet plans for ‘eventual world domination’, the West would also have to provide military and economic aid to frontline states, such as Greece, Turkey and Iran.

So the post-war Western governments continued their stand-off with the Soviet Union, a situation that became known as the Cold War. The 1947 elections in Poland were duly rigged and a communist government was returned. But the Polish government-in-exile in London continued its existence, despite the worldwide recognition of the communist puppet government in Poland. In fact, showing all the old stoicism, the London Poles continued their existence until 1991, when the old presidential seals were finally handed over to the first post-communist government in Warsaw. Throughout the late 1940s the Cold War festered with intermittent crises erupting, such as the Berlin Blockade, when the Soviets attempted to cut off Western access to Berlin. The West arranged an airlift of supplies to lift the ‘siege’ and, in 1949, the Soviets backed down. It was, however, a momentous year for other reasons – the Soviet Union developed its own atomic capability and the balance of power shifted again.

Operation Unthinkable might have been just another quiet footnote in the story of the Cold War, but in 1954 there was a bizarre incident involving Churchill and Montgomery that threatened to expose the whole plan. In a low-key speech at his Woodford constituency, Churchill suddenly announced that in 1945 he had ordered Field Marshal Montgomery to preserve captured German weapons and to be ready to reissue those arms to ‘German soldiers whom we should have to work with if the Soviet advance continued’. An intrigued press tackled Montgomery for his comments and there ensued a wrangle over whether or not Churchill had ever formally issued the order. The Soviet press immediately seized on his comments, attacking ‘Churchill’s crusade’, and there were critical articles in the British and the US press. The Chicago Tribune attacked Churchill and his wartime policy with headlines that screamed ‘Folly on Olympian Scale’. The whole episode blew up out of nowhere but more rational observers wondered why, at the height of the Cold War, the prime minister would casually disclose such controversial plans to attack the Soviet Union. Major-General Sir Edward Spears was wheeled out in defence of Churchill. ‘The whole thing is absurd,’ he countered. ‘The Times is behaving as if Sir Winston had called in Hitler for help against Russia. Hitler was out of business.’ But the prime minister still had to calm the storm by admitting that he could find no telegram in his records and that he must have issued a verbal order to Montgomery. Privately he confessed, ‘I made a goose of myself at Woodford.’