The 1st Battalion, 26th Marines, wasted no time in starting its new mission at Khe Sanh: saturation patrols in the TAOR within range of the supporting artillery. Battalion commander Lt. Col. Donald D. Newton began Operation Crockett on 14 May 1967. He stationed one rifle company each on Hills 861 and 881S, put a small detachment on Hill 950 to guard the radio relay station, and kept the rest of the battalion at the combat base for security and reserve. The infantry from the hilltop outposts patrolled continuously, ranging out as far as four thousand meters.

For the balance of May and into June, 1/26’s patrols found plenty of evidence that the NVA 325C Division still roamed the area, but they rarely saw an enemy soldier. Then, at 0100 on 6 June, the security detachment on Hill 950 frantically radioed the base that it was under a ground attack. A reaction force saddled up at the airstrip, but the radio calls grew more desperate: The enemy was in the lines; the enemy was overrunning the position; please send help. Then silence.

By the time the reaction force arrived, the fight had ended. Of the seventeen Marines on Hill 950, six were dead and nine were wounded. If 1/26 needed a reminder that the NVA still held the upper hand in the Khe Sanh hills, they had it.

The next day the enemy repeated that lesson. About two kilometers west of Hill 881S, a patrol from Bravo 1/26 was hit by NVA mortars and small-arms fire. Before the Marines recovered from that attack, a strong force of NVA soldiers poured out of a nearby tree line. A desperate close-quarters fight raged across the hillside for several hours before a reinforcing platoon from Alpha Company reached the scene and forced the NVA to break contact. Eighteen Bravo Marines died; another twenty-eight were wounded. Sixty-six dead NVA lay among the Marine casualties.

As a result of these vicious contacts, Maj. Gen. Bruno A. Hochmuth, the 3d Marine Division commander, ordered Lt. Col. Kurt L. Hoch’s 3/26 to Khe Sanh. It arrived on 13 June and headed into the hills.

There was little contact until the early morning hours of 27 June, when the NVA sent more than fifty 82mm mortar rounds flying into the combat base. The rounds killed 9 Marines and wounded 125. The combat base had barely secured from that attack when the NVA struck again. Just before dawn they launched fifty 102mm rockets at the base. Another Marine died and fourteen more were wounded in this attack.

At noon that same day, India 3/26, on a search west of the base for the enemy mortar positions, bumped into two NVA companies. The fight lasted all afternoon. Not until 1900, when Lima 3/26 arrived by helicopter, did the enemy flee. India lost eight killed, including a platoon commander, and thirty-five wounded; Lima lost its commander and thirteen others, plus fifteen wounded. An estimated twenty-five NVA died in the firefight.

After this action the enemy seemingly vanished. The two battalions continued their extensive patrols but found few NVA. As a result, 3/26 received orders on 16 July that sent it east, where enemy activity had heated up around Con Thien.

That left one battalion, 1/26, now under Lt. Col. James B. Wilkinson, the sole defenders of the northwest quadrant of Quang Tri Province. As had Lieutenant Colonel Wickwire of 1/3 before him, Wilkinson sent his men out on patrols every day. And just like Wickwire’s Marines, Wilkinson’s men rarely spotted the enemy. Throughout the rest of the summer and into the fall, the Marine patrols searched far and wide, but the NVA remained out of sight. Yet no one doubted they were out there.

In November, intelligence sources reported that two NVA divisions, the 325C and 304, had entered the Khe Sanh area. This convinced General Westmoreland that his long-hoped-for major battle with the North Vietnamese Army loomed just over the horizon. Determined to engage his foe in a decisive battle, the MACV ordered III MAF, now commanded by Lt. Gen. Robert E. Cushman, Jr., to reinforce Khe Sanh. Cushman passed the orders to the 3d Marine Division. That headquarters tapped 3/26 for a return trip to Khe Sanh. Three of its rifle companies landed at the improved airstrip on 13 December; the fourth arrived the next day. Operation Scotland began on 14 December, and the Khe Sanh hills once again felt the pounding of Marine jungle boots.

All remained quiet until just after dusk on 2 January 1968. In response to an alert Marine sentry’s warning, a quick-reaction team shot and killed five enemy soldiers dressed in Marine utilities who had been reconnoitering the western end of the combat base. A search of the enemy bodies revealed that the team had slain an NVA regimental commander and members of his staff. The corpses yielded a rich supply of documents indicating that the enemy had planned a major attack on the base. Colonel David E. Lownds, CO of the 26th Marines since August, passed the data up the line.

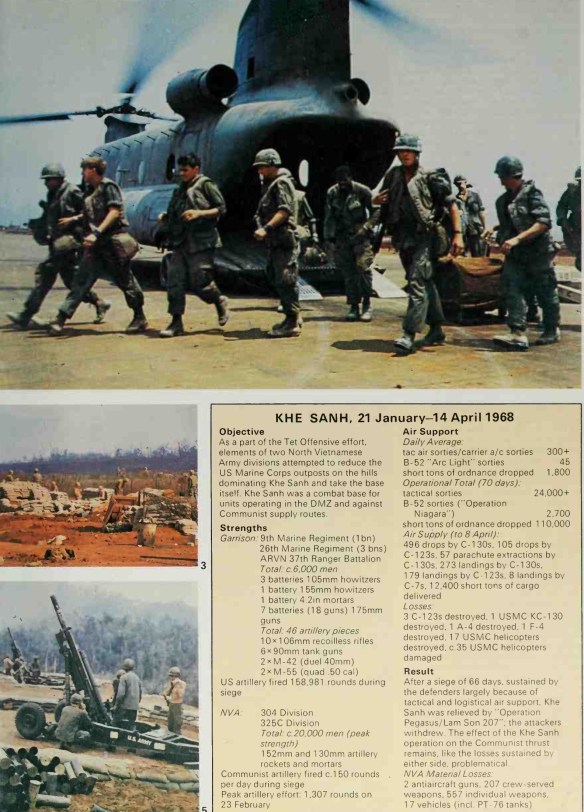

When the intelligence reached General Westmoreland, it convinced him he had been right all along. In his mind, the NVA hoped to duplicate their stunning 1954 defeat of the French at Dien Bien Phu. Westmoreland ordered a major buildup for the base. Two more Marine battalions (2/26 and 1/9) arrived at Khe Sanh in mid-January; the ARVN sent its 37th Ranger Battalion. By the end of January, five full infantry battalions, three batteries of 105mm howitzers, a battery each of 4.2-inch mortars and 155mm howitzers, and a variety of track-mounted weapons defended the base and the nearby hills.

Fearful that the NVA would have an unobstructed invasion route into South Vietnam’s two northernmost provinces if Khe Sanh did fall, Westmoreland shifted more infantry battalions north. By the end of January 1968, half of all U.S. combat troops—nearly fifty maneuver battalions—were in I Corps.

The Second Battle of Khe Sanh began on 17 January 1968 under circumstances deadly similar to those that triggered the first battle. A recon team on the southern slope of Hill 881N walked into an ambush. The patrol commander and his radioman died in the initial blast of fire; several more Marines were wounded. They and the others fell back and frantically called for help.

A platoon from India 3/26, which garrisoned Hill 881S, happened to be nearby. In response to the desperate radio calls, the platoon rushed to aid the recon team. When it arrived, the NVA fire stopped. Medevacs flew in and carried the wounded recon team members back to Khe Sanh. The India Company Marines returned to Hill 881S.

Two days later, another India Company patrol, sent to recover some radio codes left behind by the recon Marines, came under fire in the same area. After a brief firefight, the Marines withdrew.

These two contacts convinced Colonel Lownds that the NVA had reoccupied Hill 881N. Captain William Dabney, CO of India 3/26, received orders to conduct a company-size reconnaissance-in-force of the hill. India set out at 0500 on 20 January, after Mike 3/26 replaced it on Hill 881S. The Marines moved in two platoon columns along parallel ridge fingers leading to Hill 881N’s crest. To flush out ambushers, Dabney walked artillery up the hill in front of his men. It did not work.

Halfway up the hill, a vicious blast of automatic weapons fire and rocket-propelled grenades ripped into the right-hand column. Dabney ordered the left-hand platoon forward to flank the ambushers. That did not work either. The platoon made all of twenty feet when a flurry of hot lead erupted from a nearby tree line, decimating it.

For the rest of the afternoon, supported by artillery and air, Dabney continued his efforts to move up Hill 881N. Not until 1730, with seven dead and thirty-five wounded to care for, did Dabney throw in the towel. He ordered his battered company back to Hill 881S.

That same day an enemy deserter revealed that both the NVA 325C and 304 Divisions were, indeed, in the hills outside Khe Sanh. In fact, he said, his former comrades planned an attack on Hills 861 and 881S that night. Colonel Lownds immediately sent word to the outposts to be prepared.

At thirty minutes past midnight on 21 January, the first of several hundred NVA rockets, mortar shells, and rocket-propelled grenades slammed into Kilo 3/26’s positions on Hill 861. When the barrage ended, bursts of enemy machine gun fire raked the hillside. Deep in their bunkers, Kilo’s Marines gripped their weapons and prayed.

At 0100 more than 250 enemy soldiers started up Hill 861’s southwest side. Despite the Marines’ best efforts, the enemy soldiers breached their perimeter and poured into Kilo’s positions. The CO, Capt. Norman J. Jasper, Jr., went down from a direct hit on his command bunker. Unable to continue, he turned command over to his exec. The close-quarters, ferocious fight drove the Marines from their prepared positions to higher ground along the hill’s crest.

From his CP on Hill 881S, Captain Dabney watched the nearby battle unfold. Because he anticipated an attack on his position, he could only wait. However, after several hours of quiet around Hill 881S, Dabney decided he was not in the bull’s-eye that night. He ordered his mortars to fire in support of Kilo.

Despite the beating they had taken, Kilo’s Marines had a lot of fight left. At 0500 they counterattacked. Down the enemyfilled trenches they went, taking on the NVA in the most vicious hand-to-hand combat imaginable. The Marines won. At 0700 they radioed Colonel Lownds that they still held the hill.

Lownds had but scant minutes to savor the good news. From Hill 881N the enemy launched more than sixty 122mm rockets and one hundred 82mm mortar shells at the base. Dabney’s Marines witnessed a rare spectacle, akin to a world-class fireworks display, as the rockets headed toward the Khe Sanh Combat Base, trailing showers of sparks across the morning sky. Seconds later, explosion after explosion erupted throughout the base. The blasts ripped the runway’s steel matting to shreds, tossed helicopters about like toys, collapsed bunkers, destroyed tents, and zinged shards of red-hot shrapnel into human flesh.

Worst of all, one of the first rockets landed in the middle of the ammo dump. A colossal secondary explosion rocked the entire east end of the base as the bulk of more than fifteen hundred tons of pyrotechnics went up and sent flaming debris down on the base. To add to the destruction, numerous barrels of aviation fuel burst from the heat and poured rivers of fire onto the base.

That same night, NVA infantry attacked the South Vietnamese troops who garrisoned Khe Sanh village. Colonel Lownds had to turn down their plea for help. He told them to abandon the village and come to the combat base.

With the enemy now between the combat base and Lang Vei and in control of Route 9, Khe Sanh was truly cut off. The comparisons to the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu increased, but General Westmoreland remained optimistic. Indeed, he welcomed the presence of the NVA around Khe Sanh, for he had one advantage the French had not had: airpower. With the massive destructive power available from the sky, Westmoreland could easily destroy his foe. He also began to plan for the relief of Khe Sanh. He would leapfrog the U.S. Army’s 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile) down Route 9 from Ca Lu and reopen the highway. He would then send the cavalry into the hills and annihilate the NVA.

Then the Tet Offensive erupted.

On 30 January 1968, well-coordinated attacks by Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army units were launched all across South Vietnam. Over the next two days, thirty-six of forty-four provincial capitals were attacked. Every major airfield was bombarded by mortars. And enemy sappers nearly overran the massive U.S. embassy complex in downtown Saigon.

About the only major allied base not attacked was Khe Sanh. None of the five NVA divisions that U.S. intelligence reported to be in western Quang Tri Province joined in the offensive. Westmoreland believed that he knew why. He explained the countrywide attacks by announcing, “This is a diversionary attack to take attention away from the north, from an attack at Khe Sanh.”

It would be some weeks before Westmoreland accepted the truth—that the NVA movement on Khe Sanh had been the diversion. The NVA wanted to pull allied troops away from the cities and the populous coastal areas. Only then could their General Uprising–General Offensive succeed. That it did not is a testament to the valor of the individual American fighting man, backed by a nearly unlimited supply of supporting arms.

The relative quiet at Khe Sanh lasted until 2 February. On that date more rockets fell on the base. One hit an Army Signal Corps communications bunker, killed four, and temporarily cut the base off from the rest of the world.

Two days later, super-secret electronic sensors detected a large body of men near Hill 881S. By carefully calculating their route, the Fire Support Control Center (FSCC) at Khe Sanh identified a target box north of Dabney’s position. On signal, five hundred high-explosive artillery shells pummeled the target box. When no attack developed against Dabney, the men of the FSCC congratulated themselves.

Shortly after 0400 on 5 February, the NVA dropped a tremendous volley of mortar rounds on Echo 2/26, newly ensconced on Hill 861A. As soon as the last of the 82mm shells erupted, an NVA force estimated at battalion size, about four hundred men, threw themselves at the freshly strung barbed wire barrier. Sappers blasted passageways through the wire, and enemy infantry poured through the gaps.

The Echo Marines gave ground as they fell back to the center of the perimeter. Echo’s CO, Capt. Earle G. Breeding, called down massive quantities of artillery around his position. But the enemy kept coming. By 0500 they held a quarter of the hill.

The surviving Marines summoned a reservoir of courage few men knew they possessed, and they counterattacked. At close quarters, too close in most cases to use the M16, the plucky Marines stormed down the trenches and killed NVA with grenades, bayonets, and bare hands until they reclaimed the lost positions. By 0630 it was over. No less than 109 enemy bodies lay on the hill. Given the ferocity of the fight, Echo suffered relatively light casualties: 7 dead and 35 wounded.

At 2000 on 6 February, U.S. Army Special Forces sentries at Lang Vei heard the unmistakable rumble of approaching diesel engines. “Tanks in the wire!” The panicked cry echoed throughout the camp.

Seven enemy tanks supported by several hundred NVA infantry overwhelmed the Green Berets and their indigenous charges. At 0400 on 7 February, the camp commander radioed Colonel Lownds and asked him to execute a long-established relief and rescue plan.

Lownds refused. As far as he was concerned, a night movement to Lang Vei amounted to suicide because there were NVA between the base and Lang Vei. Also, the combat base had been under a mortar and rocket attack since 0100. Even if he had had a spare rifle company to send, dispatching it would have seriously weakened his own defenses. The Green Berets were on their own.

By late afternoon, the fight for Lang Vei ended in victory for the NVA. Of more than 500 defenders, only 175 survived. Only 14 of 24 Americans reached safety, and 11 of those were wounded.

Over the next seven weeks, the defenders of Khe Sanh endured daily artillery and rocket attacks. Each day at least a hundred shells, and on some days more than a thousand, hit the base or its outposts. Every day men died or were wounded. In the first four weeks of the siege, more than 10 percent of the defenders became casualties. Although soldiers in earlier wars had endured heavier shelling, the defenders of Khe Sanh suffered more because of the persistence of the barrages and their inability to stop them. Even B-52 Arc Light missions failed to halt the enemy artillery.