2015: National Security Strategy and Strategic Defence and Security Review – SDSR 2015: On 23 November 2015, the recently-elected Conservative government published the results of another defence review. This was undertaken in a very different context to 2010. British combat operations had ended in Iraq (2009) and Afghanistan (2014) but new threats had emerged. Russia was re-asserting herself militarily; China had become a substantial naval power and was claiming sovereignty of large parts of the South China Sea; whilst the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) was considered a serious threat to UK security. Also, after considerable American pressure, it had been announced on 10 July 2015 that Britain would commit to continuing to spend 2 per cent of its GDP on defence every year until 2020.

SDSR 2015 described how the UK’s armed forces might look in 2025 [above] — for the proposed Royal Navy structure – and sought to plug the worst of the capability gaps created by SDSR 2010. For the RN, there was mixed news. Positively, the review confirmed a decision announced in 2014 that both QEC carriers would, after all, enter service to ensure that one would be continuously available as the core of a maritime task group. More negatively, the previous plan to replace all thirteen remaining Type 23 frigates with the same number of new Type 26 Global Combat Ships was reduced to eight; the cost of the new ships was simply too high. Instead, design studies would begin for a less sophisticated but cheaper general-purpose light frigate, a concept the RN has long resisted. The carrot was that more than five may eventually be built, increasing the size of the escort force.

Other major announcements impacting the RN included:

Confirmation that four ‘Successor’ strategic missile submarines would be delivered, although later than previously planned, as part of renewal of the Trident nuclear deterrent.

Planned orders for two additional ‘River’ class patrol vessels, as well as three new logistic support ships for the RFA.

Investigation of the potential for the Type 45 class to operate in a ballistic missile defence role.

Acceleration of purchases of the F-35B Lightning II (selected for the JCA requirement) to ensure twenty-four will be available for carrier operations by 2023.

Planned acquisition of nine P-8 Poseidon MPAs to replace the Nimrods cancelled in 2010.

A slight increase in authorised (trained) personnel numbers to around 30,500 regulars.

PERSONNEL

- 32,500 regulars, including c.7,000 Royal Marines. There are also c. 5,500 reserves, of which around 1,800 are in the RFA.

NAVAL AVIATION

Main naval air stations (NAS) bases are at Yeovilton & Culdrose. Following the retirement of the Sea Harrier STOVL jets in 2006, front-line fixed wing aircraft operations are carried out jointly with the RAF, with the new F-35B squadrons to be based at RAF Marham. Up to 138 F-35s will ultimately be purchased, with 24 expected to be available for front-line use by 2023. Current main helicopter types are:

AW-101 ‘Merlin’ HM2 sea control helicopters: 30 in service

AW-101 ‘Merlin’: HC4 transport helicopters: 25 being converted to new shipborne standard from RAF HC3 configuration, replacing legacy Sea King types.

AW-159 ‘Wildcat’ HMA2 sea control helicopters: 28 in service or on order. Replacing legacy Lynx HMA8. Additional Wildcat AH1 reconnaissance helicopters drawn from a shared pool.

Additional British Army and RAF Apache attack and Chinook transport helicopters can be embarked as necessary. Insitu Scan Eagle UAVs are also used. The RAF is to order 9 P-8 maritime patrol aircraft for entry into service from c. 2020 onwards.

The next defence review is expected in 2020.

THE ROYAL NAVY IN 2015

Force Structure: The current Royal Navy force structure is set out in Table above. The submarine flotilla is focused on four Vanguard class SSBN strategic submarines and seven SSN nuclear attack boats, whilst the force of major surface combatants comprises six modern destroyers and thirteen older frigates. Other key components include an amphibious force built around a helicopter carrier, two LPD amphibious transport docks and three auxiliary LSD dock landing ships (operated by the RFA) and an amphibious infantry brigade that includes three Commandos (battalions) of Royal Marines. The Future Force 2025 described by SDSR 2015 will be very similar with the notable exception of entry into service of the two new carriers Queen Elizabeth and Prince of Wales from 2017 onwards. This will result in the decommissioning (probably in 2018) of the current helicopter carrier Ocean, whose crew is needed to help man them. The last Invincible class carrier, Illustrious, has already been withdrawn from service, in 2014.

After the closure of numerous establishments in the 1990s and early part of the current millennium, most forces are based at or near the three remaining naval bases at the Clyde, Devonport and Portsmouth. In addition to its presence at its main air stations at Culdrose (HMS Seahawk) and Yeovilton (HMS Heron), the Fleet Air Arm has a growing presence at RAF Marham, from where it will jointly operate the F-35B from 2018.

Organisation: The command and the administrative structures of the Royal Navy had been greatly simplified since the early 1990s. For example, superfluous formations such as frigate and destroyer squadrons have gone, and many senior positions abolished or downgraded. Nevertheless, the RN still receives considerable negative publicity for having more admirals than major warships.

The First Sea Lord & Chief of Naval Staff (1SL) is the professional head of the Royal Navy. Until 1995 he was a 5* Admiral of the Fleet, thereafter a 4* Admiral. 1SL effectively reports to the Chief of the Defence Staff (CDS) – the professional head of the British Armed Forces and the most senior uniformed military adviser to the Secretary of State for Defence and the Prime Minister.

The 1SL is Chairman of the Naval Board, the body having practical responsibility for running the RN. His key lieutenants are the Second Sea Lord (2SL), a 3* Vice Admiral who is responsible for personnel and infrastructure, and the Fleet Commander & Deputy Chief of Naval Staff, a 3* Vice Admiral based at Navy Command Headquarters at Portsmouth.

Accountable to the Fleet Commander is the most senior sea-going post: Commander United Kingdom Maritime Forces (COMUKMARFOR). A 2* Rear Admiral; he will only go to sea for major exercises or combat operations. The two key RN operational formations in the first decade of the millennium were the UK Carrier Strike Group (UKCSG) and the UK Amphibious Task Group (UKATG), each commanded by a 1* Commodore. The UKCSG was disbanded following the elimination of the RN’s strike carrier capability in 2010, with UKATG being renamed the Response Force Task Group (RFTG). However, with the pending entry into service of Queen Elizabeth, the UKCSG organisation was re-established in 2015 and the commander of RFTG reverted to being titled Commander Amphibious Task Group.

Operations: By the start of the twenty-first century, the RN seemed to have successfully reorganised itself from its Cold War tasks. The previous focus on antisubmarine warfare in the North Atlantic had been swept away in favour of expeditionary forces capable of global deployment. Indeed, the RN’s frigates and destroyers were scattered around the world in a manner not seen since the 1960s.

In the immediate aftermath of SDSR 2010, the RN continued to operate at a high tempo. However, this was not sustainable, placing excessive demands on equipment and personnel. The RN has thus retrenched considerably, cutting some commitments altogether (e.g. participation in many standing NATO maritime groups), and making others part-time (e.g. its presence in the West Indies).

Since 1980, the RN has maintained a near continuous presence in the Arabian Gulf and Indian Ocean, under titles such as Armilla Patrol, Southern Watch and Operation ‘Kipion’. These operations were always considered temporary, so only ad-hoc support arrangements were made. The need for a permanent base in the region was finally recognised in December 2014 when the decision was announced to build the Mina Salman Support Facility in Bahrain, to be named HMS Juffair when completed in 2016. A 1* Commodore is already headquartered in Bahrain to command maritime forces in the region.

The new base will be the home port for four mine-countermeasures vessels, plus a ‘Bay’ class support ship and a repair ship. The base will also be frequently used by other RN assets in the region, typically including a Type 45 destroyer, a Type 23 frigate, a nuclear attack submarine and an RFA replenishment ship. The two escorts regularly participate in maritime security operations such as the multi-national Combined Task Force 150, the NATO-led Operation ‘Ocean Shield’, and the EU-led Operation ‘Atalanta’ – all essentially maritime security and counter-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and off the Horn of Africa.

Other standing RN commitments include:

One Vanguard class SSBN continuously on patrol, providing the UK’s nuclear deterrent.

One frigate or destroyer at high availability in UK waters (the fleet ready escort).

A frigate or destroyer, with an accompanying RFA support ship, in the South Atlantic.

A patrol vessel (normally Clyde) based in the Falkland Islands.

The ice patrol vessel Protector, on station in the Antarctic region for most of the year.

One ship in the West Indies during the winter hurricane season: in 2015 this was the patrol vessel Severn.

Fishery, economic and maritime security protection duties around the UK.

In addition, the RFTG is exercised annually, usually by a four-month deployment to the Mediterranean.

ISSUES & CHALLENGES

The RN currently faces many challenges, the most significant of which include:

Maintaining Britain’s Nuclear Deterrent: The current four Vanguard class SSBNs are beginning to shows signs of their age and need replacing. They were due to start decommissioning in 2023 but this has had to be delayed, as the first of four new ‘Successor’ class submarines is not now expected to enter service until the early 2030s. Even this timetable assumes that detailed design and construction work proceeds to schedule.

If the ‘Successor’ project suffers from the lengthy delays that affected the Astute class submarines, there is a serious risk that the RN may eventually be unable to maintain a continuous at-sea nuclear deterrent.

Lack of Personnel: In October 2015, the Royal Navy had 22,480 trained regular personnel, and the Royal Marines 6,970, for a trained total of 29,450 regulars. There were another 3,030 regular personnel under training. This compares with a total of 35,240 trained personnel in October 2010.

Current manpower levels are insufficient to keep the fleet fully manned; in particular a shortage of 500 engineers badly affected operations during 2015. In smaller branches and specialisations (some with less than a hundred personnel), it is also difficult to maintain training capabilities, a coherent career path, and a reasonable work-life balance. The submarine service is a particular concern; it has become so small that the loss of just a few highly skilled and experienced senior rates and officers could cripple the service. Also new joiners (from commanding officers downwards) no longer have the opportunity to learn the ropes in conventional submarines; they now go straight to billion-pound nuclear submarines.

During the SDSR 2015 deliberations, the RN reportedly requested an extra 2,000 regular personnel, but got around 400, which will be slowly added to the 2015 authorised trained strength of 30,270. In spite of the increasing use of reservists, this may not be enough to stop a difficult situation getting worse.

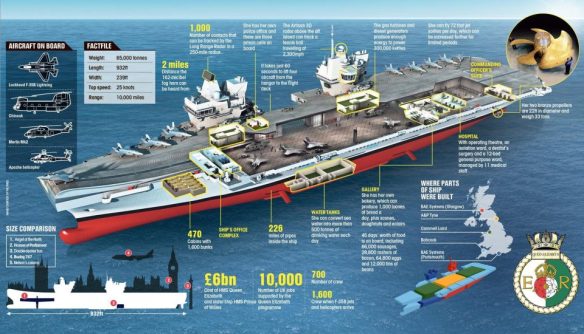

Creating Carrier Enabled Power Projection: A big challenge facing the RN is regenerating its carrier force by bringing the two Queen Elizabeth class aircraft carriers in to service and then using these to deliver the concept of Carrier Enabled Power Projection (CEPP).

CEPP was an idea developed as the RN fought to save the carrier programme from cancellation in SDSR 2010. It shifted the rational for the new carriers beyond their original carrier strike role (operating up to thirty-six JCAs). Instead, it emphasised the flexibility of the Queen Elizabeth class – particularly with regard to operating helicopters and supporting amphibious operations. This has required changes to the design to allow them to embark a substantial military force and operate a mixed air-group comprising both fixed-wing aircraft and multiple rotary-wing types effectively. Prince of Wales will be completed to the revised design, with – presumably – Queen Elizabeth eventually being retrofitted. The operating concept is much closer to that of the US Navy’s LHDs than traditional carrier operations, and represents a huge learning curve for the RN. Although Queen Elizabeth will enter service in 2017/18, she is not expected to be fully operational and able to deliver all aspects of CEPP before 2022.

CEPP presents a number of risks which will have to be managed. Firstly, it is dependent on the continuous availability of a QEC carrier, and the RN will struggle to keep one always fully manned and operational. Secondly, the QEC will be a hugely expensive, high value unit; accordingly escorting and supporting the carriers will dominate future RN operations. Thirdly, CEPP is ‘joint’, its application requires the availability and integration of British Army and RAF assets into embarked operations. Finally, the concept has killed a tentative plan for a low-cost replacement for Ocean, though there will be occasions where a helicopter carrier would offer a more appropriate and cost-effective presence than a Queen Elizabeth-based group. The Queen Elizabeths are now going to have to work closely with amphibious ships such as the Albion class; for reasons as basic as differences in maximum speed this will not be easy. New tactics and operational procedures will have to be developed.

Too few Submarines and Escorts: The RN has too few attack submarines and escorts to meet all the demands placed on the force. Operational studies have repeatedly shown that the RN needs at least eight attack submarines but funding permits only seven. Indeed, there are often only six when a Trafalgar class boat decommissions before its replacement Astute class enters service. The RN currently struggles to deploy even two submarines simultaneously.

The availability of the six Type 45 destroyers is lower than hoped, whilst the availability of the Type 23 frigates is being affected by their life extension programme, involving lengthy refits. No more than five or six escorts can be deployed at the same time – barely enough to meet current commitments. Moreover, a high-value aircraft carrier will need escorting from 2018.

The RN is reluctantly being forced to use patrol vessels for tasks previously fulfilled by escorts. In the long term it is hoped that the new light frigate can be built in sufficient numbers to increase the size of the escort force.

Maintaining the Industrial Base: A Defence Industrial Strategy (DIS) published by the MOD in December 2005 said ‘For submarines we have endorsed, but not yet committed funding for a 24-month SSN build drumbeat … The longer-term surface ship production drumbeat is of the order of one new platform every one to two years.’ This was to prove optimistic.

Table above shows ships ordered in the years 1990 to 2015. It can be seen that these peaked in 2000–1 as the MOD began to implement SDR. Indeed, the proposed construction programme was so large that UK shipyard capacity was expected to be inadequate, and the RAND Corporation was asked to develop a plan to optimise its use. Unfortunately by the time RAND completed their report in 2005, much of the construction programme was already in doubt. Progress continued on the £6.5bn Queen Elizabeth class aircraft carrier project only by the RN sacrificing almost everything else.

In 2015, despite work on the Queen Elizabeth class winding down, SDSR 2015 delayed the first Type 26 order until 2017. As a stop-gap, the MOD is buying five ‘River’ Batch 2 patrol vessels – three were ordered in 2014, with two more planned for 2016. Capable of world-wide deployment and equipped with a helicopter deck, they are a big step-up from the three Batch 1 ships, which will presumably be sold.

As a result of the lack of RN orders, and a failure to win exports orders, many UK shipyards have closed, most recently the Vosper Thorneycroft (later BAE Systems) facility in Portsmouth in 2014. BAE Systems Maritime – Naval Ships is now the only UK company able to build major warships, with a facility for submarines at Barrow-in-Furness, and two yards in Glasgow (at Govan and Scotstoun) for surface ships. BAE Systems has effectively become a monopolistic supplier, and the MOD is struggling to maintain a UK naval construction capability without paying excessive prices. For example, the MOD has baulked at the price being quoted to it for the Type 26s, and even hinted that it was prepared to order them overseas – a serious threat given the MOD’s landmark order in 2012 for four Tidespring class Fleet Tankers from DSME of South Korea.

UK naval construction has become shaped not by the needs of the RN, but by budgets and what the Treasury considers to be the lowest rate of naval construction rate that will allow BAE Systems Maritime and key suppliers such as Rolls-Royce to survive and thus preserve critical industrial capabilities.

Poor Public Relations: The Royal Navy has suffered from a relatively poor public image in the early part of the twenty-first century. The glory days of appearances in James Bond films, and the 1970s TV series Warship and Sailor are long gone. When the RN does feature in the media, it is often in a negative context: cost overruns, ship groundings, excessive drinking and the like. A particular PR disaster was the seizure by Iran in 2007 of two small boats from the frigate Cornwall carrying fifteen RN/RM personnel; their subsequent parading in the glare of the world’s media was described by Admiral Sir Jonathon Band, then 1SL, as ‘one bad day in our proud 400-year history’. An attempt in 2010 to repeat the success of Sailor with the TV series Ark Royal backfired due to the carrier’s obvious lack of aircraft, and the untimely announcement that she was to be decommissioned as a defence cut.

Perhaps even worse is the lack of naval experience and advocacy in political circles; Minister of State for the Armed Forces Penelope Mordaunt (a Sub-Lieutenant in the RNR) being an important exception. It is also notable that no admiral has held the top post of Chief of the Defence Staff since 2003. One former First Sea Lord, Admiral Sir Jonathon Band, concluded in a speech he made in October 2011, ‘ … the nation as a whole has forgotten its maritime tradition and nature of existence’. The RN badly needs a high-profile success story. It is also to be hoped that the Queen Elizabeth class will become an impressive symbol of British military power in the same way the carrier Charles de Gaulle has become for France.

A FINAL COMMENT

The early years of the twenty-first century have been difficult time for the Royal Navy. The UK’s military focus on land conflicts during the period has had a negative impact in terms of funding and, consequently, force levels for the naval service.

However, the security of the UK and its national interests are inextricably linked to the sea. The UK is physically an island nation dependent on seaborne trade; it is the fifth largest economy in the world; it has world-wide interests and commitments; and it wants to remain a permanent member of the UN Security Council. Given these factors, the RN may well have reached its nadir; indeed, the advent of the Queen Elizabeth class carriers may mark the start of a recovery.