French King Philip Augustus of France and Richard the Lionheart disputing the direction of the Third Crusade.

The Siege of Acre was the first major confrontation of the Third Crusade.

Richard the Lionheart and his fleet arrived in the Holy Land in early June 1191. He first attempted to dock in Tyre, but he found that Philip had left orders for the soldiers not to allow the English to come to land. Philip and his current ally, Conrad of Montferrat, did not want to take the chance that Richard would treat Tyre as he had Cyprus. Sailing onward the next day, Richard turned south.

Before long, his fleet encountered a strange vessel. Though the ship appeared French and flew the French flag, its occupants did not understand European naval communication, nor did they speak the French language. As a few men from Richard’s fleet sailed toward the vessel, the ship drew up for battle and began to bombard the soldiers with its arrows and guns. Realizing the true situation, Richard ordered an attack. His galleys rammed the enemy ship, which soon began to sink. Those of its crew who were not killed were taken prisoner. From them, Richard gleaned valuable information.

The ship had been transporting soldiers to Acre, a city located on the coast at the extreme north of modern-day Israel. There, the crusaders had been fighting to take the well-defended city since August 1189, when Guy de Lusignan, the weak king of Jerusalem, made a poor tactical decision in beginning the siege. Philip’s arrival in April with the French reinforcements and supplies had improved the situation of the attackers, but Guy had sent messages to Richard while the king was delayed on Cyprus asking him to come quickly. Now Richard finally made his way to Acre.

On June 8, Richard’s fleet sailed into the harbor at Acre. The crusaders celebrated and cheered with fanfare and trumpets. The Muslim defenders in the city saw their hopes of survival growing slimmer and slimmer. Richard, with his bold and daring persona and talent as a military leader, quickly began to take control of the campaign. One method he used to gain power was to offer the men fighting for him a greater sum per month than Philip offered his soldiers, thereby gaining the allegiance of many of the crusaders at Acre. As a result, Richard had plenty of men to guard the most important of weapons, the siege machines. Philip’s weapons, on the other hand, were repeatedly subjected to attack and suffered great damage due to the lack of guards.

Political turmoil and rivalry between the crusading forces continually influenced the European rulers’ decisions. When both Richard and Philip fell ill, it was Philip who recovered first. He used this time to his advantage, trying to take back command over the invading force. Without Richard’s agreement, Philip went ahead with a plan to assault Acre’s walls directly. Unfortunately for Philip, this move resulted in disaster for his army, and the control of the field was left even more firmly in Richard’s hands.

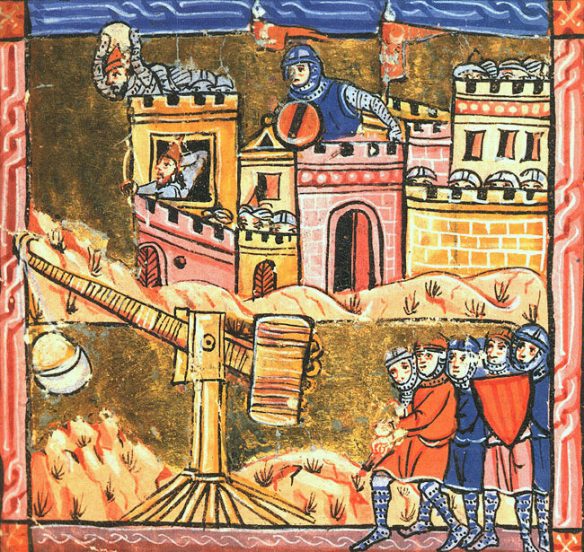

Richard, starting to recover, ordered the beginning of a highly effective catapult barrage of the city walls. He also oversaw the construction of military mines; tunnels dug under the walls. These tunnels would then be collapsed with the intent of bringing down a section of the wall. Between the catapult and mines, Richard’s men made a significant breach in the wall. However, it wasn’t enough for the army to break through into the city. The rubble of the walls provided excellent terrain for the defenders to fight against any direct onslaught. Richard, always clever and resourceful in war, made a new proclamation to his men. Anyone brave enough to sneak up and take a stone from the wall would receive a gold piece. This proved not to be enough of an inducement for such a high-risk, foolhardy task, so Richard upped the price. At last, his soldiers began to risk their necks to steal the wall itself. Not surprisingly, this plan resulted in extremely high casualties—more than the army could consistently sustain. Richard would need yet another plan if he intended to take the city. He began to plot for a final, decisive assault.

On July 4, Richard and Philip jointly refused a proposal of surrender from the battered city’s defenders. The kings began their attack two days later, on July 6. Less than a week passed before the defenders again offered terms for their surrender. The first time, they had done so without the agreement of their commander, Saladin, who was stationed with his troops outside the city. This time, even Saladin agreed to let Acre’s defenders barter for surrender. The English and French kings turned down this second offer as well, demanding more. At last, the defenders offered, in addition to relinquishing the city, to give the crusaders the relics from the True Cross previously captured by Saladin, pay a huge sum, release Christian prisoners, and leave behind their weapons and goods. Finally, the European leaders agreed to the terms. Before long, the banners of Richard and Philip were raised over the city as their soldiers celebrated. Duke Leopold of Austria, who had also taken part in the siege, attempted to raise his banner as well. Richard, incensed by this seeming attempt to encroach on his glory, did not stop his men from tearing down and vandalizing the banner—a serious insult to the duke, who would not soon forget it.

Despite this minor conflict, the evacuation of the defending forces occurred peacefully. Richard and Philip gave orders that the enemy soldiers should not be mistreated, and the men left the city in an organized fashion. The next issue confronting the leaders of the crusading force was the management of the conquered city. There were hostages who had to be guarded and property that had to be doled out between invading leaders. Churches were re-dedicated by Cardinal Alard of Verona. Nobles were rewarded for their services, though some were not content with what they received and returned home to Europe. Richard and Philip had to make decisions about the rights of businesses and merchants—decisions that would severely impact the economic future of Acre. Beyond these necessities, Richard was constantly involved in diplomatic negotiations with Saladin and other rulers.

As July neared its end, another notable change came to the leadership of the crusade. King Philip announced that he desired to return to Europe. There may have been any number of motivations for Philip’s actions. He had already fought and would receive the benefits of being a crusader—benefits both to his kingly reputation and in the obligations the Church would now owe him. He would also be able to return before Richard, putting Philip at an advantage on European soil. Moreover, Philip had never had the same level of passion for military might and the strategy of warfare that Richard had. In any case, Richard met this declaration of Philip’s intentions with relative indifference. Though King Richard would lose an ally on the battlefront, he would now be the only king on the crusade; with no competition for control, Richard could arrange every aspect of the war as he saw fit. After a variety of negotiations, settling remaining issues between the two kings and the effects of their conquests, Philip departed on the last day of July.

Richard now took complete command of the troops in the Holy Land. The results were soon unpleasantly bloody. Richard entered negotiations with Saladin since it was not Saladin who had made the official peace agreement at Acre. Saladin agreed to honor the terms of the agreement in full. This included payment of money and exchanges of prisoners and hostages from the two sides; Saladin requested that this should be done over a period of three different meetings.

At the first meeting, on August 11, a disagreement broke out. Richard’s men claimed that Saladin should have delivered not just a certain number of prisoners, but specific prisoners. Saladin did not agree that this had been part of their terms. Richard, impatient, waited three more days as negotiations dragged on with no promise of a conclusion. Then he ordered action. The Muslim prisoners were brought outside Acre’s city walls in chains—over 2,000 men. Richard next commanded his men to slaughter the prisoners. This decision, shocking to his contemporaries and utterly opposed to the ideas of honor in the practices of war made popular through song and poetry, goes entirely against the picture that Richard sometimes seems to have adapted for himself of the chivalrous knight. In addition, his decision meant that the number of his men who were prisoners of Saladin would die in exchange. But the exchange of prisoners had now been dealt with, and Richard was ready and eager to take his troops to new battles. On August 22, Richard led his forces south, leaving the city of Acre with its victories, conflicts, and tragedies behind.