On 12 November 1940, Pilot Leonard Cheshire’s Whitney was hit by flak over Colongne, but he got it back to the airfield.

102 Squadron would have the second highest losses in Bomber Command.

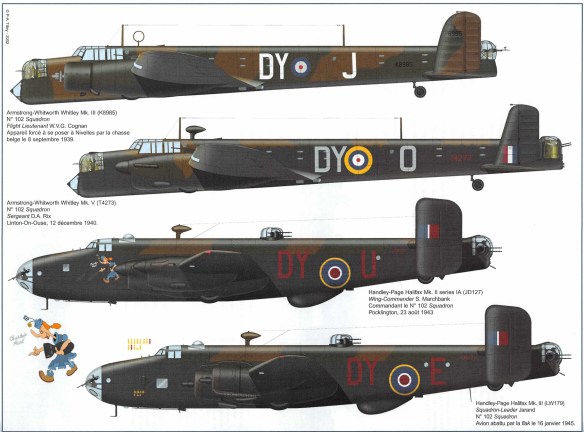

The squadron was active from the second day of the Second World War, dropping leaflets in the night from 4 to 5 September 1939 over Germany. From 1 September till 10 October 1940 the squadron was loaned to RAF Coastal Command and spent six weeks carrying out convoy escort duties from RAF Prestwick, before resuming bomber raids. Operations Record Books seen at the Public Record Office in Kew show that 2 Whitley Mk.Vs flew out of Topcliffe on 27 November 1940 to bomb “docks and shipping” at Le Havre. One of these planes “was not heard from after take off” but the other returned safely having dropped its two 500lb and six 250 lb bombs successfully. By February 1942 the Whitleys were replaced by the Handley Page Halifax. The squadron continued for the next thirty-six months to fly night sorties (including the thousand bomber raids) over Germany. In 1944 the squadron attacked rail targets in France in preparation for the invasion.

Training on Halifax Bombers

A couple of days later all the newly formed crews went by train to RAF Topcliffe in Yorkshire, which was a Heavy Bomber Conversion Unit. Here the crews flew together for the first time. Our aircraft were Halifax IIs. We did many circuits and bumps during the day and at night, so that our pilot could get used to flying the 22-ton aircraft. We flew cross countries – day and night – to various places in the UK so that the navigator could gain experience. On one flight we were lower than we should have been and found ourselves almost in the balloon barrage over Liverpool – we did have cable cutters on the wings but were not keen to test them! We did searchlight liaison flights over various cities, in which the search light crews were to pick us up and our task was to avoid them. They never did get us, unlike the German searchlights. Another activity was fighter liaison in which the Brownings in the turrets were replaced by camera guns. We would then be attacked by a Spitfire that also had a camera gun and we practiced our evasive action drill and the Spit pilot his attacking technique, all of which was recorded on 16mm film, which we were shown later. After about a month at Topcliffe crews were posted to various squadrons. Ours was one of several that went to 102 Squadron at Pocklington in 4 Group in the county of Yorkshire. A small farming community, it had three pubs, an old Anglican church and two rather ordinary hotels, which would serve you a very restricted wartime meal for five shillings. This was the top price allowed by the Government to any restaurant in wartime.

We were all keen to go on ops; little did we know that our crew was to be the only one to survive. The majority of my ops were over the Ruhr, hitting most of the main cities such as Essen, Munich, Cologne, Frankfurt, Manheim and Stuttgart. Then of course there was Berlin and three to Italy, as well as mine-laying around the Friesian Islands, so I had an exciting and eventful war and lived to tell the tale. On one occasion we were on our way to Essen in very heavy flak, when there was a loud explosion in the aircraft and a rush of cold air and the Halifax bounced, around. The Skipper checked on the intercom that we were all OK and the flight engineer went to see what the damage was. A piece of shrapnel had detonated the photo flash, which exploded and destroyed its launching tube and blew a jagged hole in the starboard side of the fuselage just behind my turret. We measured it back at base and it was about 5 feet long by 3 feet high. This resulted in a gale blowing through the aircraft and made it very difficult for George to handle. Nevertheless we flew to the target – Krupps – and bombed it and set course for base. About half way home and still over enemy territory we lost an engine due to mechanical trouble. This reduced our airspeed even more and we lumbered home an hour later than the rest of the squadron. Being behind the main stream and flying low as we approached the English coast we attracted the attention of the Navy, who fired at us with pom-poms, despite us firing off the colours of the day. I could hear the pom-pom-pom of the guns above the sound of our three engines. When counting the hits on our plane, as we always did, we wondered how many were from enemy fire and how many from the Navy. It was surprising how much damage the Halibags could sustain and remain in the air. I would fly on 17 different Halifaxes during my tour (nine of which were shot down or crashed, some only a few days after they had got us home safely) and I wondered how many of them had the components that I had made.

Lost over Cologne

As the October dawn began to break over the fields of England, Flying Officer George R Harsh RCAF, the 102 Squadron Gunnery Officer, with cold and trembling fingers, fumbled amidst the straps and buckles and flaps of his flying gear and extracted the flask of brandy from his hip pocket and took a long, gurgling belt of this time-tested restorative. Described as ‘grey as a badger’ and looking like a ‘Kentucky colonel; a wild, wild man with a great spreading nose and a rambunctious soul’, Harsh was an American born in Milwaukee and educated in North Carolina and at Oglethorpe University in Atlanta. Having found and circled over their home base at Pocklington, the crew spotted the operations officer standing at the end of the runway, signalling with his green Aldis lamp the call letters of the squadron and their aircraft: O-Orange. With the four magnificent Merlin Rolls-Royce engines straining against the lowered flaps, the crew settled in for the touch-down. Then, having taxied to the dispersal site the pilot shut off the engines and the sudden silence tore at their ear drums. One by one, they dropped out of the hatch and walked slowly over to the waiting lorry. Harsh wrote:

The birds would just be starting their cheerful greetings to this new day and for some reason the sound always startled me, as though I thought those birds had no right to be any part of this crazy business. And yet I loved that sound, for I knew they were English birds and that once again I was on friendly soil. The same WAAF who had seen us off the night before and had watched unconcernedly as we each in turn had unbuttoned and peed on the port wheel for luck would be standing beside her lorry waiting for us with a big cheerful smile on her English-complexioned face. We had taxied out of the dispersal site and she had seen us off with that big smile and her arm held aloft and her fingers giving the Victory sign and this morning the smile was still there and so was her unvarying greeting: ‘Morning, chaps. Have a nice trip?’

And the reply would come from my polite British fellow crew members, as though we had just returned from a holiday cruise to the Caribbean. ‘Veddy nice, thenk you.’38

Life had started out with great expectations for George Harsh. He lost his father when he was twelve but at his death a half-million dollars was put in trust in young George’s name. Then at age 17 Harsh shot a man in a hold-up, for kicks. He was sentenced to die in the electric chair, but at age 18 his sentence was commuted to life in prison and he spent the next twelve years on a Georgia chain gang. Harsh wielded a shovel for 14 hours a day; slept in a stinking cage; fought off the sexual attacks of other prisoners and learned how to survive a hell that would have killed most men. He was pardoned when he saved the life of another prisoner by performing an improvised appendectomy. Less than a year later Harsh had volunteered for flying service in the RCAF.

At 4 o’clock on the afternoon of 5 October, all air crew members at Pocklington were ordered over the tannoy system to report to the briefing room. The target for over 250 aircraft was Aachen, though George Harsh was not scheduled to fly that night. At take-off time he stood at the end of the runway, with the operations officer, enjoying this brief respite from what the American called ‘this orgy of killing’. During the past two weeks 102 had taken more than its usual share of casualties. The operations officer with his Aldis lamp signalled the aircraft and got them airborne, one following right on the tail of the other. The third-from-last Halifax was standing poised, waiting for the ‘go’ flick of the light when suddenly the pilot signalled Harsh and the ops officer. In a dogtrot they hurried over to see what the trouble was. The pilot, Warrant Officer Frederick Arthur Schaw RNZAF, with a frantically jabbing finger was motioning them towards the rear turret. Schaw’s was one of the green crews that had been sent to the squadron from the replacement depot. In fact this was the first combat operation for this crew. Running around to the rear turret and motioning with his hand because of the wash of the props and the tinny roar of the engines, Harsh got the gunner to understand that he wanted him to swing the turret around and open the door. ‘What’s the problem?’ Harsh bellowed at him over the noise. The gunner, a huge farm boy from Yorkshire, held out his hand; and there, nestling in the great palm, were the remains of what had once been a finely adjusted gun-sight. ‘It coom apart in me ’and!’ he shouted in his Yorkshire accent. It was as though a bear had got hold of a fine, jewelled Swiss watch.

Harsh continues:

‘Get the bloody hell out of there!’ I roared at him and as he extricated his lumbering bulk from the turret. I snatched off his parachute harness and buckled it on myself over my best uniform. That plane had to go on the mission and there had better be someone in the turret who could hit a target without the aid of a gun-sight. Perhaps I could do something with the help of the tracers.

As we got airborne and headed out across the Channel, the realization of how stupid I had just been crashed into my mind – and it was that parachute harness which acted as the catalyst. For some reason known only to himself the ploughboy had been wearing an unneeded sheepskin-lined leather flying jacket and the harness had been adjusted to all that bulk. There was now enough slack in the harness to hang a horse and it was all hanging down between my legs. If I had to bail out and the parachute opened, that slack would snap taut right into my crotch! With this sickening picture in mind I reached behind me for the adjusting buckles but in the cramped quarters I couldn’t do anything with them, so I pulled the slack up around my chest and offered a small prayer. By now I was beginning to feel that I had used up all my luck, but maybe it would hold for one more time.

For an hour or more we droned along uneventfully. We had not run into any heavy concentrations of flak and miraculously no night fighters had challenged us. Intelligence had assured us the flak would be light. Suddenly a cold thought entered my mind: for the past half-hour I had not noticed any other bombers flying in our direction and this despite the fact we should have been right in the middle of the bomber stream. Slowly I swung the turret in its full arc – nothing out there but an occasional fleecy patch of white cloud, shimmering in the bright moonlight. And then I looked down at the ground 8,000 feet below us. Oh, no! But blinking my eyes wouldn’t make it go away. The Kölner Dom! The majestic twin spires of the Cologne Cathedral were pointing into the sky at me. The bulk of the old Gothic edifice was bathed in moonlight and the moonlight was shimmering from the waters of the river as it made its unmistakable bend around the church. There we were, right on top of Cologne … alone.

The pilot must have instinctively sensed that something was wrong, for I heard a microphone click on and then his voice crackled in the earphones. ‘Hullo navigator! Where are we?’ For what seemed interminable seconds there was dead silence and then the well-bred, English-public-school accents of the navigator came over the intercom. ‘I’m fucked if I know old boy.’

The groan of despair did not even have time to escape my lips before everything seemed to begin happening at once. The eerie purple light of the radio-controlled searchlight, the master searchlight of the Cologne air defence system locked onto us and having seen this happen to other bombers I knew there would be no escaping it. No manoeuvring, no ‘jinking’, no diving nor turning nor any amount of speed would shake off that relentless finger. With the range signalled to them from this automatic light the entire searchlight complex now locked onto us and we were ‘coned’, the most dreaded thing that could happen to any bomber crew. The sky around us and the aircraft itself were lighted up like Broadway on New Year’s Eve and then it came. The German gunners had a sitting duck for a target and all they had to do was pour their fire up into the apex of that cone and there was no way for them to miss. In the bright, blinding light there was no flashing coming from the flak bursts now but suddenly our whole piece of illuminated sky filled with brown, oily puffs of smoke. Pieces of shrapnel began hitting us and it sounded like wet gravel being hurled against sheet metal. Then we started taking direct hits and the aircraft jumped and bucked and thrashed and pieces of it were being blown off and I could see them whipping past me. Then the fire started and I could smell it and see the long tongues of flame streaming out from the wings. The intercom was now dead and so was the hydraulic system that operated the turret but with the manual crank I quickly turned the turret around, opened the doors and was preparing to push myself backwards out into the sky when a burst of light, fine shrapnel sprinkled my whole back. It felt as though the points of a dozen white hot pokers had suddenly jabbed into me. My one prayer at that moment was that the flak had not cut the parachute harness draped over my back. The parachute harness! Oh, God … get that slack out of your crotch! I dropped, clutching the slack around my midriff with my left hand and pulled the rip cord on my chest pack with my right. I was now conscious of the dead silence through which I was falling. Gone was the aircraft with its roaring engines and miraculously the flak had stopped. But one searchlight glued itself onto me and began following me downward. Then the chute opened and my fall was suddenly, jarringly halted and I bobbed upward like a yo-yo in the hand of some idiot giant. With a tearing, rending noise the slack snapped taut around my chest and I felt my whole rib cage cave in. Then I passed out.

Aachen was hit with little Path Finder marking and bombing was scattered. A 214 Squadron Stirling taking off from Chedburgh near Bury St. Edmunds crashed almost at once and a 106 Squadron Lancaster caught fire on landing at Langar after an early return. Eight aircraft – five of them Halifaxes – were shot down over the continent. Q-Queenie on 103 Squadron flown by Warrant Officer Kenneth Fraser Edwards fought its way through a thunderstorm, but just as course was being set for home, a Bf 110 attacked and badly damaged the Halifax and set fire to both wings. The fires intensified and spread and when Edwards gave the order to bail out they were at quite a low level. He and two other members of the eight man crew died on the aircraft and four men were taken prisoner. Two of the missing ‘Hallybags’ were on 102 Squadron. One crashed at Stokkel with the loss of all seven crew. Warrant Officer Schaw was killed; all seven of his crew were taken into captivity. George Harsh spent two weeks in a hospital in Cologne before being incarcerated in Stalag Luft III, where he took charge of tunnel security in the ‘X Organisation’.

‘Home for Christmas’ was the standard joke in prisoner of war camps but tunnelling went so smoothly at Luft III that Harsh said thoughtfully one morning, ‘You know, this time it might really be home for Christmas for some of us’ and for once nobody laughed.

Mannheim

Bomber Command had sent 271 aircraft to Mannheim, comprising 159 Wellingtons, 95 Stirlings and 17 Halifaxes. The target was effectively marked by the Pathfinders and bombing was reasonably concentrated causing extensive damage. The bombers lost eighteen of their number (6.6 per cent of their total) – nine Wellingtons, seven Stirlings and two Halifaxes, the majority of these falling to fighters. With clear conditions it was in ideal night for the single-engined fighters but the difficulty that the three Bf 109s had in bringing down the Stirling emphasised the problems faced by these fighter pilots who were not used to the size of an aircraft such as the Stirling, which presented problems of estimating range and of combat at night. The overall losses had been high – but not as high as for the other raid mounted that night. The Command despatched 327 bombers to attack Pilsen, the aiming point being the important Skoda armaments factory. Thirty-six of the 197 Lancasters and 130 Halifaxes (eighteen of each) were lost on this raid and despite bright moonlight the attack was poor as the target was misidentified.

Halifax HR663 of 102 Squadron was one of the aircraft that didn’t make it back, although the pilot, Squadron Leader Lashbrook DFC DFM (on his thirty-sixth operation) and three other members of the crew managed to evade capture (two crew were taken prisoner and the Rear Gunner, Flying Officer G Williams was killed). Debrief of the evaders summarised the fate of the aircraft: ‘After having bombed the target the aircraft flew into the Mannheim region at 9,000 feet and experienced very severe icing. After climbing to 14,000 feet the ice began to evaporate and as the height of the cloud tops became les the aircraft reduced height to 9,000 feet.

‘In the Ardennes region an aircraft was seen going down in flames on the starboard side – tracer was seen and it was assumed to be a fighter attack. Approximately 3 minutes later another aircraft was seen going down in flames on the port side. The Pilot told the Mid-Upper Gunner to keep a sharp lookout and almost immediately bullets hit the aircraft. The fighter was not seen but was apparently attacking from astern and below. All members of the crew said they were OK. The Pilot put the aircraft into a steep dive to port and at once saw there was a very fierce fire between the Port Inner engine and the fuselage. … After 3,000 feet loss of height the Pilot found that he could not pull the aircraft out of the dive as the controls were not working properly, nor could he throttle back the port engines as the throttle control rods were loose or severed. The Pilot gave the order to bale out. The Pilot left, he believes, last and as he was trying to leave, the aircraft went into a spin. Eventually he got free at less than 1,000 feet and made a heavy landing.’

With total losses for the night of fifty-four aircraft (8.8 per cent of the force) this was the highest number of losses in a single night to date, although fourteen of the aircraft managed to ditch in the sea on the way home and a number of aircrew were rescued.

Berlin

C-in-C Bomber Command Harris continued the Battle into 1944 and Berlin was attacked six times in January twice early in the month and four times late in the month – with nearly three weeks respite in the middle. The two attacks in the first few days of January brought another increase in loss rates, both being around 7 per cent, and disappointing results as the bombing was poorly concentrated. The two attacks on consecutive nights were different in that most losses on 1/2 January were outside the area of Berlin whereas the following night the controllers had mad an early prediction that Berlin was the target and they had 40 minutes to collect fighters at appropriate beacons. One of the effects of this was that the first aircraft over the target – the Pathfinders – were hit hard, losing ten aircraft Bomber Command paused for a few weeks with very few operations of any type being flown; the ‘Big City’ was still the favoured target but Bomber Command assessment was that less than 25 per cent of the city had been destroyed, an underestimate if German records are taken into account, a disappointing result when lesser campaigns had resulted in destruction levels on other cities of 50–70 per cent.

When the briefing curtains were drawn back on 20 January crews groaned as they saw the tape leading once more to Berlin, although the direct route had been changed in favour of a more diverse approach. This was another maximum effort with 769 bombers, 264 of which were Halifaxes but it followed the same pattern as previous raids with fighters getting in amongst the bombers and with a cloud-covered Berlin proving hard to hit. It was not a promising return for the Halifax, with twenty-two of the 264 aircraft being lost. It was 102 Squadron’s ‘turn’ to suffer and the Pocklington-based squadron lost five of its sixteen Halifaxes over enemy territory plus another two that crashed in England (it lost a further four aircraft the following night).

The Halifaxes were once more taken off the Berlin roster for the next raid and it was 515 Lancasters and fifteen Mosquitoes that returned to the city on 27/28 January. The bombers had a reasonable run to the target and bombed on sky markers as the aiming point was cloud covered; fighter combats took place on the return route and overall losses remained at over 6 per cent. It was back to a maximum effort the next night and a route via Denmark to try and throw off the fighters. The tactic was only partly successful and when the bombers arrived over Berlin the fighters were waiting and most of the forty-six losses occurred in the vicinity of the target. It was however the most accurate raid for a while as cloud was broken and the Pathfinders were able to lay ground markers. The planning for both of these raids had included diversionary operations to divert German defensives as well as offensive support operations against night fighter airfields and with an increasing number of Serrate-equipped Mosquito night fighters flying with the bomber stream. Two nights later 534 bombers were en route for the final attack in January. The northern route via Denmark once more prevented combats until the Berlin area but several bombers were shot down in the target area. Cloud was thick over Berlin but bombing was reasonably effective.

Gardening

The employment of the heavy bomber force was essential as in February 1942, Harris had made an offer to the Admiralty to lay an average of 1,000 mines a month – a ten-fold increase! However, he did stress that this was not to have a detrimental effect on the main bomber offensive. What it gave Harris was a political lever to use on the Admiralty, and Churchill, whenever the cry went up for Bomber Command to help out in the naval war.

The Air Staff agreed the commitment on 25 March 1942, and the policy was implemented. During 1942 the minelaying effort absorbed some 14.7 per cent of the total Bomber Command operational effort, with 4,743 sorties, during which 9,574 mines were laid (1941 figures had been 1,250 sorties and 1,055 mines). There had also been an increase in the loss rate, up from 1 per cent to nearly 4 per cent, although with marked variation depending upon the operational area – Kiel had the lowest rate and the Weser estuary the highest. Throughout 1942 and 1943 the squadrons sent crews to find nominated stretches of water in which to place their cargo. It was certainly looked on by most crews as a bit of light relief after the hazards of ‘Happy Valley’ (the Ruhr) or Berlin. Ken Pincott was with 15 Squadron: These were looked on as an easy operation because most often the main attack that night would be against a mainland target by the bomber force. Apart from a little flak and occasional fighter, the odds of survival were much higher.’

Tom Wingham was operating with 102 Squadron on the night of 28 April 1943 in Halifax JB894/X: ‘Kattegat, two 1,500 lb mines. Good visibility although 7/10 cloud base 2,000 feet. Mines laid as ordered from 1,500 feet heading 156 at 176 TAS, after timed run. Avoided flak ships but saw some light flak. Easy run. Surprised to hear later of the heavy losses suffered that night.’

No less than 207 aircraft had been tasked with minelaying that night, 167 reported successful missions (a total of 593 mines), but twenty-two aircraft were lost (seven Lancasters, seven Stirlings, six Wellingtons and two Hampdens) – at over 10 per cent, by far the most costly night of minelaying recorded by the Command. This large-scale effort broke the previous sortie record, set only the night before, of 160 sorties.

Not all minelaying sorties were straightforward, Harry Hull was air gunner in a Halifax of 10 Squadron: ‘We were briefed for a minelaying trip and, full of confidence that there could not be many more, set off, but barely half an hour from base I felt a thump, thump, thump from under the aircraft which just did not sound normal. The skipper sent the bomb aimer down to inspect the bomb bay for the vibration. Upon opening the inspection hatch he found a mine had broken free from one of the holding straps and was swinging backwards and forwards with the movement of the aircraft. After waiting for the end of the radio silence period we contacted base and they gave us a jettison area – they certainly did not want an unexploded mine rolling down the runway when we landed!’

On rare occasions aircraft witnessed the results of the minelaying effort; the Bomber Command Quarterly Review carried this account from a 305 Squadron Wellington. ‘At about 2100 on 16 February 1943, this aircraft was laying mines in the Bay of Biscay. The night was extremely clear, there was bright moonlight and the sea was calm. The aircraft was making a run-up at a height of 500 feet when she saw a U-boat crash-dive ahead.

‘It took her less than a minute to reach the position and she had just passed over it when there was a violent explosion which shook her considerably. The bomb aimer and rear gunner both saw a big column of spray and the latter saw what he took to be the tail of the U-boat standing almost vertically out of the water. It disappeared after a short while and nothing more was seen. Mines had also been laid on previous sorties in this area.’