Capture of Aguinaldo, March 23, 1901

Starting in the autumn of 1899, the time Emilio Aguinaldo decided to inaugurate guerrilla war, the Filipino leader became a marked man. American units vied with one another for the glory of capturing the insurgent leader. None surpassed the zeal of Batson’s Macabebe Scouts. “I hunted one of his Generals to his hole the other night,” Batson wrote his wife, “and captured all his effects as well as his two daughters.” Such relentless pursuit forced Aguinaldo to keep on the move. He and his small band of loyal staff endured exhausting treks across rugged terrain. They were often hungry, reduced to foraging for wild legumes supplemented by infrequent meat eaten without salt. Sickness and desertion reduced their ranks. Aguinaldo’s response was periodic exemplary punishments, drumhead courts-martial, firing squads, and reprisal raids against villages that either collaborated with the Americans or failed to support the insurgents. “Ah, what a costly thing is in dependence!” lamented Aguinaldo’s chief of staff.

Aguinaldo took solace from the occasional contact with the outside. In February 1900 he received a bundle of letters including a report that the war was going well with the Americans suffering “disastrous” political and military defeats. A correspondent in Manila affirmed that the people “were ready to drink the enemy’s blood.” The high command’s ignorance of outside events was startling. For example, Aguinaldo and his party learned from a visitor that five nations had recognized Philippine independence. However, his chief of staff reported that “we do not know who these five nations are.” Indeed, the chief of staff candidly recorded that since fleeing into the mountains “we have remained in complete ignorance of what is going on in the present war.”

During his exodus Aguinaldo was unable to exercise effective command of his far-flung forces. This did not change after he sought refuge in the remote mountain town of Palanan in northern Luzon. All Aguinaldo could do was write general instructions to his subordinates and issue exhortations to the Philippine people. His efforts had scant effect on the war. What was important was his mere existence. He was the living symbol of Filipino nationalism. In addition—and this mattered to the ilustrados who managed the war at the regional and local levels—as long as he remained free the insurgents could say that they fought on behalf of a legitimate national government.

Aguinaldo’s efforts to maintain a semblance of command authority led to his downfall. In January 1901 an insurgent courier, Cecilio Sigis-mundo, asked a town mayor for help getting through American lines. His request was standard practice. The mayor’s response was not. He happened to be loyal to the Americans and persuaded the courier to surrender. Sigismundo carried twenty letters from Aguinaldo to guerrilla commanders. Two days of intense labor broke the code and revealed that one of the letters was addressed to Aguinaldo’s cousin. It requested that reinforcements be sent to Aguinaldo’s mountain hideout in Palanan. This request gave Brigadier General Fred Funston an idea.

Funston interviewed Sigismundo to learn details about Aguinaldo’s headquarters (and, according to Aguinaldo, subjected him to the “water cure,” an old Spanish torture whereby soldiers forced water down a prisoner’s throat and then applied pressure to the distended stomach until the prisoner either “confessed” or vomited; in the latter case the process started again). Palanan was ten miles from the coast, connected to the outside world by a single jungle trail. Although Americans had never operated in this region, obviously the trail would be watched. Funston conceived a bold, hugely risky scheme to capture the insurgent leader. He selected eighty Tagalog-speaking Macabebes who disguised themselves as insurgents coming to reinforce Aguinaldo. Funston armed them with Mauser and Remington rifles, typical weapons for the undergunned insurgents. To make the reinforcements seem more believable, four Tagalog turncoats performed the role of insurgent officers. To make the bait even more enticing, five American officers acted as prisoners and accompanied the column. Nothing if not personally brave—he had earned the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1899—Funston was one of the five.

MacArthur approved of the desperate plan—his chief of staff wrote the secretary of war that he did not expect ever to see Funston again—and on March 6, 1901, a navy gunboat sailed from Manila Bay to deposit the raiding party on a deserted Luzon beach sixty straight-line miles from Palanan. So began the most celebrated operation of the guerrilla war. No mission like this could unfold seamlessly. A harrowing 100-mile trek that called upon physical stamina and quick-witted improvisation brought the column to Palanan on March 23, 1901. To allay any possible suspicions, Funston sent runners ahead to deliver two convincing cover letters. They were written on stationery that had been captured at an insurgent base. Not only did they bear the letterhead “Brigade Lacuna” but they were signed by the brigade’s commander, an officer whose writing Aguinaldo was certain to recognize. In fact a master Filipino forger who worked for the Americans had signed the letters. The letters informed Aguinaldo of the impending arrival of the reinforcements he had requested along with a special bonus of captured American officers.

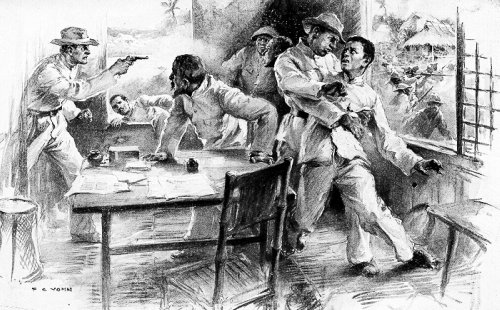

While Funston and his fellow officers hid in the nearby jungle, the column’s sham insurgent officers went ahead. A last obstacle remained: the unfordable Palanan River. Two “officers” crossed in a canoe and gave instructions for the Macabebes to follow. The two “officers” approached Aguinaldo’s headquarters to see a uniformed honor guard formed to greet them. The cover letter had done its work. Aguinaldo was completely deceived. For a very nervous thirty minutes the two “officers” regaled the insurgent commander with stories about their recent ordeal. Finally the Macabebes arrived. They formed up across from the honor guard as if in preparation to salute Aguinaldo. Then at a signal they opened fire at the startled headquarters guards. Inside Aguinaldo’s headquarters, the two “officers” seized Aguinaldo. Meanwhile, Funston and his band emerged from the jungle to take charge. The effect of the surprise was so overwhelming that Funston’s commandos managed to escape with their prize and rendezvous with the waiting gunboat.

Funston took Aguinaldo to Manila, where MacArthur treated him with great courtesy, even to the point of having his staff dine with the insurgent leader. Within a few days Aguinaldo was exploring terms of surrender. Within a month he issued a proclamation calling on all insurgents to surrender and for Filipinos to accept United States rule.

In a campaign suffering from slow and indeterminate results, Aguinaldo’s conversion was something concrete. MacArthur and the War Department took full advantage, proclaiming the incident the most important single military event of the year. Among the skeptics were the midshipmen of the Naval Academy standing in the left-field bleachers at the first Army-Navy baseball game ever played. Arthur MacArthur’s son Douglas was Army’s left fielder. The midshipmen heckled Douglas with the chant:

MacArthur! MacArthur!

Are you the Governor General Or a hobo?

Who is the boss of this show?

Is it you or Emilio Aguinaldo?

Indeed, the claim that Aguinaldo’s capture was decisive overstated the facts. Instead, although it was not clearly apparent at the time, MacArthur’s stern policies had already begun to erode insurgent strength significantly. While his conversion did inspire the surrender of five prominent insurgent generals, and hundreds of soldiers either turned themselves in or ceased active operations, his removal from the scene had little practical impact for many insurgents. They were accustomed to recognizing the authority of their local commanders. Those commanders, in turn, had been acting like regional warlords for some time and consequently were used to a high level of autonomy.

Aguinaldo’s capture was a brilliantly conceived and boldly executed coup. As had been the case when Otis proclaimed victory after dispersing the regular insurgent forces, senior American leaders anticipated a prompt end to the war. Unfamiliar with the ambiguous nature of counterinsurgency, they again overestimated the value of a single “decisive” success. On July 4, 1901, as MacArthur neared the end of his tour of duty in the Philippines, he reported that the armed insurrection was almost entirely suppressed. The army had squashed armed resistance in nearly two thirds of the hostile provinces. In the United States a pleased President McKinley began a domestic victory tour designed to heal the sharp political divisions created by the war.

Again the general commanding the field forces and the commander in chief were wrong. The insurgency survived the loss of its leader and persisted for more than another year.