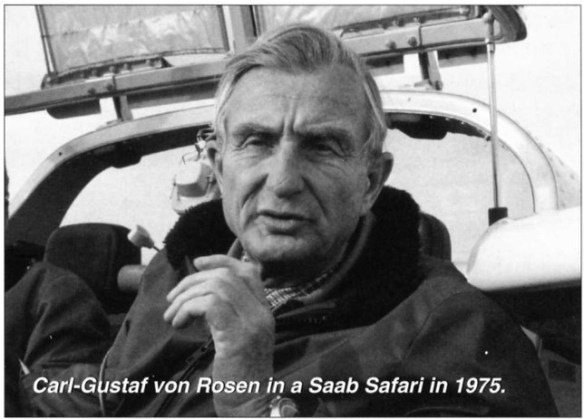

Count Carl Gustav von Rosen, the elderly Swedish nobleman who reformed the Biafran Air Force in 1969, is seen in the cockpit of a Minicon `light sporting aircraft’. Up to 18 Minicons were converted into light strike aircraft fitted with rocket-launchers and made a series of successful raids between May and October 1969.

One of the ex-Swedish MFI-9B ‘Minicons’ is positioned within its dispersal bay at Uga strip during the final month of the war. The starboard MATRA rocket launcher pod is clearly visible beneath the wing. The simplistic overall two-tone camouflage scheme suited well the operational conditions of Biafra bush strips. Biafran Air Force Officer, Johnny Chuco, stands beside his aircraft as minor attention to the cockpit is carried out.

A Biafran Air Force MFI-9B ‘Minicon’ in its bush clearing beside Uga strip. This view shows well the positioning of the underwing rocket pods

A Swedish aristocrat, Count Eric von Rosen, whose aunt Karin was married to German First World War fighter ace, Hermann Goering, was earning his living as a stunt pilot when Italy invaded Abyssinia in 1935. He volunteered to fly for the Red Cross delivering doctors and medicines to remote mountain passes, risking Italian anti-aircraft fire in the process. After the fall of Addis Ababa, von Rosen had stopped in Cairo on his way back to Sweden to raise money for the Abyssinian resistance when he was contacted by British intelligence officers. For the next few months, von Rosen agreed to fly arms and supplies, using his single-engined Fokker F VIIa, from British airstrips in Egypt to Abyssinian guerrilla fighters.

During the so-called phoney-war period that followed Poland’s defeat on 5 October SIS worked closely with the intelligence services of other European governments, including those of France, Belgium and Holland, and it soon became evident that inserting and communicating with British agents in Germany was becoming an almost impossible task. As the Allies and Germany faced each other, waiting for the next offensive, a short sharp campaign broke out on 30 November between the Soviet Union and Finland in what became known as the Winter War. Foreign volunteers from several countries, including Sweden, Britain and the United States, boosted the small but well-trained Finnish armed forces.

Among them was Count von Rosen, who had donated his faithful Fokker to the Finnish Red Cross and was now flying a former KLM Douglas DC-2 airliner converted into a bomber by the Finnish Air Force. Carl von Rosen flew the makeshift bomber on several long-range missions in harsh winter conditions to bomb targets deep in the Soviet Union. He later purchased a pair of Koolhoven F.K.52s for Finland. Beatrix Terwindt, a former KLM air hostess and a colleague of Eric von Rosen’s wife, was arrested in 1943 by her German reception committee. They assumed that she was another SOE agent but knowing little of ‘N’ Section or its operations, Terwindt could reveal nothing of value to her interrogators. Realising that she was of little value to them, she was sent to Ravensbrück and later Mauthausen concentration camps; but against the odds she managed to survive. With only limited international assistance, the Finns more than held their own against the overwhelming numbers of Soviet attackers, whose offensive was halted by mid-December.

As Norway fought a losing battle for its freedom, Hitler’s forces unleashed their long expected Blitzkrieg against France and the Low Countries on 10 May. During Operation ‘Fall Gelb’, more than two million German troops smashed their way from Rotterdam to the outskirts of Paris within a month. One of those caught up in the battle for Amsterdam was the redoubtable Count von Rosen, now a captain with the Dutch national airline, KLM. Hours before the Germans overran Schiphol Airport on 13 May, a DC-3 was loaded with military and state papers and KLM’s chief pilot Captain Parmentier took off for England. His co-pilot was von Rosen. On arrival at Heston the Swede, who had flown KLM’s Berlin route, was regarded with suspicion and about to be interned, before a member of the security service for whom he had worked in Abyssinia was able to vouch for him.

Carl von Rosen caught a Finnish boat to Sweden the following day, from where he travelled back to Holland searching for his wife, a former KLM stewardess, but he was arrested by the Gestapo on the border. After mentioning his family’s relationship with Hermann Goering, he was released on the understanding that he would leave Holland as soon as he found his wife, but when he located her she insisted on staying in Holland. To avoid his own arrest von Rosen returned alone to Stockholm, spending the duration of the war as an ABA Swedish Airlines pilot on the vital courier run between Stockholm and Berlin. He never saw his wife again. She joined the Resistance, was later arrested and sent to Dachau concentration camp, where she committed suicide.

Biafra

The Nigerians would not allow in relief flights, including Red Cross, to help Biafra’s ten million people, one-tenth of whom were living in refugee camps. They said that such flights inhibited the ability of the Nigerian air force to carry out its mission. The only food getting through arrived on a few night flights by daredevil pilots sponsored by international relief organizations.

Most of the world, preoccupied with the year’s busy agenda, regarded this war with a fair amount of indifference, not supporting the Biafran claim to nationhood but urging the Nigerians to let relief planes get through. But on July 31 the French government, despite predictions that de Gaulle’s days of foreign policy initiatives were over, departed from its allies and its own foreign policy by stating that it supported Biafra’s claim to self-determination. Aside from France, only Zambia, Ivory Coast, Tanzania, and Gabon officially recognized Biafra. On August 2 the war became a U.S. political issue when Senator Eugene McCarthy criticized President Johnson for doing little to help and demanded that he go to the United Nations and insist on an airlift of food and medicine to Biafra.

Americans responded by creating numerous aid groups. The Committee for Nigeria/Biafra Relief, which included former Peace Corps volunteers, was looking for a way to get relief into Biafra. Twenty-one leading Jewish organizations, Catholic Relief Services, and the American Committee to Keep Biafra Alive were all looking for ways to help. The Red Cross hired a DC-6 from a Swiss charter company to fly in at night, but on August 10, after ten flights, the flights were suspended because of Nigerian antiaircraft fire.

Then, on August 13, Carl Gustav von Rosen, landed a four-engine DC-7 on a little dirt runway in Biafra. The plane, carrying ten tons of food and medicine, had come in on a new route free from Nigerian radar-guided antiaircraft guns.

Von Rosen had first become famous in a similar role in 1935 when he defied the Italian air force and managed to fly the first Red Cross air ambulance into besieged Ethiopia. In 1939, as a volunteer for the Finnish air force in the Finnish-Soviet war, he flew many bombing missions over Russia. And during World War II he flew a weekly courier plane between Stockholm and Berlin.

After successfully landing in Biafra, von Rosen then went to São Tomé, the small Portuguese island off the coast of Nigeria, where warehouses of food, medicine, and ammunition were stacked up ready for Biafra. There he briefed the pilots on the air corridor he had discovered. He had flown this corridor into Biafra twice to make sure it was safe. The first time he did it in daylight, even though daylight runs were unheard of because of the risk of interception by the Nigerian air force. But von Rosen said he had to be able to examine the terrain before attempting a night run. He said that he didn’t care whether the pilots used the corridor for food or guns. “The Biafrans need both if they are to survive.” The tall Scandinavian with blue eyes and gray hair called what was happening there “a crime against humanity. . .. If the Nigerians go on shooting at relief planes, then the airlift should be shielded with an umbrella of fighter planes. Meanwhile we are going to continue flying and other airlines will join in.”

He was greatly concerned by the plight of the Biafrans and on his release trom Transair at the age of sixty returned to Sweden to form an air force for Biafra. He purchased five MFI-9Bs as sporting aircraft and shipped them to France for the fitting of rocket launchers by Matra. From there they were shipped to Libreville, where they were assembled and camouflaged. They were not given markings or serials. The first strike by the light aircraft, popularly called ‘Minicons’, was on 22 May 1969 against the airfield at Port Harcourt: flying from Orlu, four aircraft claimed two MiGT 7 s and two Il-28s damaged or destroyed. On the 24th they attacked the airfield at Benin City, claiming damage to one MiG and one 11-28. On the 27 th the airfield at Enugu was the target, and on the 28th some damage was caused to the oil facilities at Port Harcourt. The Minicons transferred operations to Uli and continued to sting the Federal forces, who by now were surrounding a much contracted Biafra with a view to starving the country into submission. Von Rosen returned to Europe, where he purchased more MFI-9 aircraft from private owners, allegedly for the Abidjan Flying Club but transferring them to Biafra in October. The main task of the Minicons was to inhibit the oil industry, which they did to some effect. The hard-pressed Biafrans finally collapsed after their airstrip at Uli was overrun in 1970, severing their only remaining supply link.

Despite his controversial methods, Count von Rosen would later be remembered for his efforts to modernize relief efforts to remote conflict zones. One of the notable figures assisting Count Carl Gustav von Rosen was Lynn Garrison, an ex-RCAF fighter pilot. He introduced the Count to a Canadian method of dropping bagged supplies to remote areas in Canada without losing the contents: a sack of food was placed inside a larger sack before the supply drop. When the package hit the ground, the inner sack would rupture, but the outer one kept the contents intact. With this method many tons of food were dropped to many Biafrans who would otherwise have died of starvation. Later models of the Malmö Flygindustri MFI-9 became the SAAB MFI-15 Safari, with official modifications, developed from the Biafran concept, to facilitate the dropping of food supplies from underwing hard points. Von Rosen was utilizing this type in Ogaden, Somalia when he was killed during a rebel ground assault, 13 July 1977.

Correspondents who managed to get into Biafra reported extremely high morale from the Biafrans, who usually said to them, “Help us win.” The Nigerians launched ever more deadly assaults led by heavy shelling, and the Biafrans continued to hold their ground, training with sticks and fighting with an assortment of weapons acquired on the European market. But by August Biafran-held territory was only a third the size of what it had been when the people had declared their independence the year before. With hundreds of children starving to death every day, eleven thousand tons of food had piled up ready for shipment from various points.

Odumegwu Ojukwu, the thirty-four-year-old head of state, a British-educated former colonel in the Nigerian army, said, “All I really ask is that the outside world look at us as human beings and not as Negroes bashing heads. If three Russian writers are imprisoned the whole world is outraged, but when thousands of Negroes are massacred . . .”

The U.S. government told reporters that it was helpless to aid Biafra because it could not afford to give the undeveloped world the appearance that it was interfering in an African civil war. It was not clear if this decision took into account the impression it had given the world that it was already interfering in an Asian civil war. But it did seem true that there was a growing resentment in Africa of Western aid for Biafra. This, not surprisingly, was particularly true of Nigerians. One Nigerian officer said to a Swiss relief worker, “We don’t want your custard and your wheat. The people here need fish and garri. We can give them that, so why don’t you find some starving white people to feed.”