At least fifty sappers moved silently through the wire that moonless night. The sappers, bareheaded and naked except for green shorts, were covered with charcoal and grease so that even in the shimmering light of explosions and burning bunkers they would be only half-seen shadows to the stunned grunts-wraiths, specters who were here, there, and everywhere, methodically slinging grenades and satchel charges into position after position, then coldly shooting the survivors as they tried to scramble out.

The attackers were later identified by a battalion Kit Carson Scout as belonging to the 409th VC Main Force Sapper Battalion. The scout had been a member of this elite unit before coming over to the other side, and he recognized a former comrade among the handful of enemy dead left on FSB Mary Ann.

The 409th usually operated against softer ARVN targets in Quang Nam Province, though not under provincial control, receiving its missions instead from Military Region the headquarters for all enemy forces in the first five provinces below the Demilitarized Zone (DMZ). The sapper battalions were used selectively. Perhaps the 409th was sent into action against FSB Mary Ann to grab big headlines at minimal cost. Perhaps MR 5, unaware that the 1-46th Infantry was packing up for new hunting grounds, wanted to slow down an aggressive foe that was uncovering caches and ambushing supply parties on the trails that were the logistical heart of communist operations in Quang Tin and Quang Ngai Provinces.

The allies possessed no firm intelligence on any sapper units, but they suspected that the 409th had recently slipped south from Quang Nam into Quang Tin Province to join the 402d, a sapper battalion already known to be in the area. At the time of the attack, the S2 map in the 196th Brigade TOC had the 402d and 409th plotted fifteen to twenty kilometers east of FSB Mary Ann, preparing for the anticipated surge against the ARVN. During the nine months since Mary Ann had been reopened, the NVA had studied the position in detail and had presumably prepared a sand table model for the newcomers of the 409th. Sappers sometimes rehearsed their attacks on mock U.S. positions built in their own jungle base camps.

At Mary Ann, local NVA probably served as guides for the sappers during pre-assault recons and the attack itself, after which they evacuated sapper casualties, covered their withdrawal by fire, and led them quickly away from the area. It was the sappers alone, however, who negotiated the wire obstacles and infiltrated the base. That was their specialty. With weapons slung tightly across their backs, grenades attached to their belts, and faces and bodies blackened, they slid snakelike through the brush, silently, patiently, an inch at a time, listening, watching, gently feeling the ground ahead of them. They neutralized trip flares encountered along the way by tying down the strikers with strings or strips of bamboo they carried in their mouths. They snipped the detonation cords connected to claymores, and used wirecutters on the concertina, careful to cut only two-thirds of the way through each strand, then breaking each noiselessly with their hands, holding it firmly so the large coil wouldn’t shake.

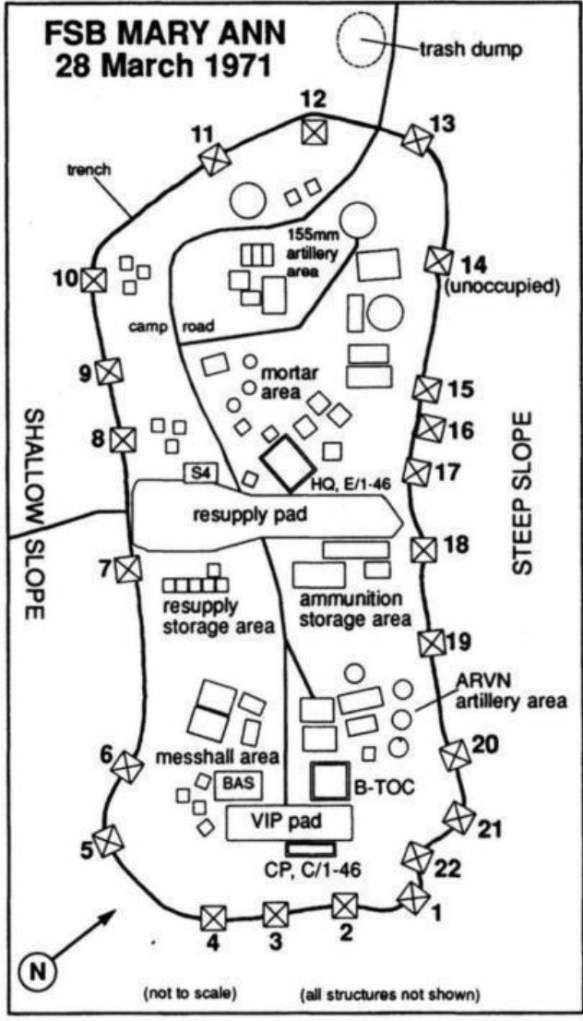

The sappers ignored Mary Ann’s northeastern side, where the slope dropped steeply to the river. They came instead from the southwest. The outer apron of double concertina was one hundred meters from the bunker line, and the sappers cut four large gaps in it, two to either side of the camp road that exited the perimeter from the resupply pad. They cut four identical gaps in the next barrier fifty meters ahead, though in places the wire was in such a state of disrepair the sappers could walk right over the rusty, mashed-down junk. It was another thirty meters to the third and final barrier, which was only twenty meters from the bunker line, and instead of risking the snap of wirecutters the lead sappers opened the way by tying the wire back with more bamboo strips. The sappers then spread out along that half of the bunker line, ready to dart into the perimeter when the mortar rounds that were to signal their attack slid down the tubes set up on the high ground north of the firebase.

Even veteran sappers were known to tremble when worming their way though a firebase’s inner wire. They were completely vulnerable there. Sappers were not supermen, and on numerous occasions alert bunker guardsthe best defense against sappers-caught the infiltrators in the wire. It helped if the wire was festooned with rock-filled cans that rattled when brushed against, and included trip flares cleverly placed under the rocks the sappers would probably pick up and move aside on their way in. It also helped if the defenders placed mock trip wires in the concertina-the more the better, for the sappers had to stop and waste time checking each one. Then there was illume and mad minutes.

Nevertheless, enemy sappers enjoyed a record of chilling successes during the Vietnam War. Air bases were a favorite target, and in February, 1965, the VC employed mortars and demolition teams to reduce the army’s Camp Holloway near Pleiku to a shambles. The shelling hit barracks buildings, and eight Americans were killed, another 126 wounded. One sapper body was left behind near the flight line where twenty-five planes and helicopters had been damaged or destroyed. Records do not indicate ARVN casualties at the base, but they were presumably substantial.

In October, 1965, a ninety-man VC raiding force penetrated the Marine air facility at Marble Mountain near Da Nang. Almost a quarter of the sappers were killed or captured, but not before they and their comrades had killed three Marines, wounded ninety-one, and practically destroyed a helicopter squadron. Nineteen choppers were blown up on the airstrip, and thirty-five damaged.

Even the elite Green Berets were given a black eye by the sappers. On an August night in 1968, sappers suddenly materialized inside the headquarters compound of the 5th Special Forces Group’s Command and Control North (CCN), on the outskirts of Da Nang, tossing satchel charges through windows as they raced through. The secret ground war in Laos was run from CCN. Given the security clearances involved, the raid received little media attention, but a dozen Green Berets were killed, along with an unknown number of their Nung mercenaries.

In May, 1969, sappers infiltrated the 101st Airborne Division’s FSB Airborne in the A Shau Valley. Twenty-six GIs were killed and sixty-two wounded in the horrific night action. Forty enemy bodies were found. Most of the enemy casualties were regular infantry who tried to follow up the sappers’ successful penetration and were chopped up in the wire by the embattled defenders.

In January, 1970, the 409th Sapper Battalion used the cover of night and a heavy monsoon rain to get into FSB Ross, even though 1st Marine Division intelligence had been tracking the unit’s movements and had reinforced the firebase in expectation of attack. Thirteen marines were killed and another sixty-three wounded. The casualties would have been worse, but most of the sappers’ water-soaked ordnance failed to explode, and the marines were able to organize a stunning counterattack. Artillery fire blocked the enemy infantry that was to have followed the sappers in, and at least thirty-eight enemy soldiers were killed and four captured. Several sappers were blown up by mortar fire from the infantry backing them up. The sappers had not been informed that a mortar barrage was part of the plan, and it threw them into some confusion after their classic penetration of the firebase defenses.

During the first week of February, 1971, a sapper force walked right into a hilltop perimeter manned jointly by the ARVN and a reconnaissance platoon from the 198th LIB, Americal Division. The VC entered through the ARVN side of the hill and demolished the position from inside out, killing five GIs and numerous ARVN. Given the timing of the raid, it was later speculated that the enemy force involved was the 409th and that the attack had been launched as something of a live fire drill in preparation for the upcoming attack on FSB Mary Ann.

In March, 1971, sappers went through 101st Airborne Division units on the perimeter of the Khe Sanh Combat Base, which had been reopened to provide helicopter support to the ARVN in Laos during Operation Lam Son 719. Three GIs were killed and fourteen wounded during the fight on the bunker line. Fourteen sappers were killed and one was wounded and captured, but the rest made it to the airstrip. The base rocked for hours with burning fuel and exploding munitions from two ammo storage areas; helicopter rockets went up like roman candles.

Less than three months later, in May, 1971, a small sapper team that got in and out without a fight blew up 1.8 million gallons of aviation fuel at the army’s huge logistical complex at Cam Ranh Bay.

The sappers of the 409th, waiting in darkness and silence between the inner row of tactical wire and the bunker line on the southwest side of Mary Ann, carried with them lessons from FSB Ross. This time the support fires would be better coordinated. This time there would be no follow-up wave of infantry to get chewed up in the wire. The sappers were spread out, probably in three- and six-man teams. Each sapper knew the plan and his part in it. They would strike from the north, south, and west, and exit through the trash dump at the northwest end of Mary Ann. Most carried folding-stock AK-47s. Some were armed with RPG launchers, and carried wicker baskets with shoulder straps on their backs filled with rocket-propelled grenades like arrows in a quiver. Each had a dozen hand grenades around his waist, many of which were simply beer and Coke cans stuffed with explosives. The sappers also carried satchel charges-twenty-five pounds of C-4 in a flat canvas bag with a pull-type fuse and a strap on top for throwing. The 82-mm mortar crews of the support element were to initiate the assault with a short barrage of HE and CS tear gas shells. The enemy rarely used gas, but in this case even some of the satchel charges were wrapped with dry CS to further confuse and disable the defenders. The shelling, which would prove uncannily accurate, was targeted against the B-TOC and company CP on the southeast half of the firebase, and the mortars and heavy artillery on the northwest half. Those were the primary targets. Under the cover of the mortar fire, the sappers would quickly cross the trench line that connected the bunkers. The six-man teams were to rush up either hill to take out the primary targets, while the smaller teams would step up to the perimeter bunkers-one team per bunker-where shocked grunts would be cowering inside under cover, unaware that the mortars had stopped firing and all the explosions were being caused by grenades and satchel charges.