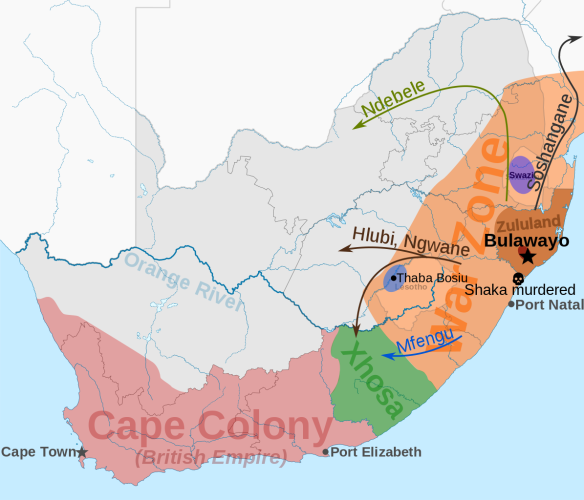

This map illustrates the rise of the Zulu Empire under Shaka (1816–1828) in present-day South Africa. The rise of the Zulu Empire under Shaka forced other chiefdoms and clans to flee across a wide area of southern Africa. Clans fleeing the Zulu war zone included the Soshangane, Zwangendaba, Ndebele, Hlubi, Ngwane, and the Mfengu. A number of clans were caught between the Zulu Empire and advancing Voortrekkers and British Empire such as the Xhosa.

During the early 1800s people in southern Africa experienced a period of upheaval characterized by increased violence, long-distance movement of peoples, the destruction of old states, and the emergence of new larger kingdoms. Historians once believed that this had been caused by the emergence of an aggressive and expansionist Zulu Kingdom under the leadership of Shaka. Since the late 1980s, revisionist historians have argued that these events were caused by various forms of colonial raiding originating from different parts of the region. Shaka’s allegedly central role was created and exaggerated by colonial writers who wanted to direct attention from their own unsavory activities. While the debate over this issue has never been fully resolved, most historians today do not accept the old view that Shaka’s Zulu caused the period of turmoil once known as Mfecane (Crushing).

For many years historians were confident that they knew the story behind the turbulence of early-nineteenth-century southern Africa. Shaka had given his new Zulu state military superiority over other African groups by inventing a new short stabbing spear that was particularly effective in hand-to-hand combat, introducing new battlefield tactics of encirclement, and creating a system of organization based on age regiments. From around 1815 to the late 1820s Shaka led the Zulu in a series of wars against neighboring Africans who were either incorporated into the new kingdom or driven away. For example, Sotho people rallied under their new leader Moshoeshoe in the mountain sanctuary of the Drakensberg. Mzilikazi, formerly an ally of Shaka, took his Ndebele group into the central part of what is now South Africa, where they used new Zulu military methods to dominate that area until attacked by Boer settlers in the late 1830s. Allegedly, the Mpondo Kingdom of Faku lost all its cattle to raids from the neighboring Zulu and had to abandon almost half its territory. Refugees fled along the Indian Ocean coast, were eventually taken into Xhosa society as the Mfengu or Fingo (from Ukumfenguza, meaning “to seek work”), and were supposedly rescued by the British Army in 1835, when they were brought into the Cape Colony under the protection of Christian missionaries. Central to this view of history was that Shaka’s wars had depopulated much of the central part of what is now South Africa, which made it easy for Boers to expand into that area during the Great Trek of the late 1830s and 1840s. Although colonial historians of the early twentieth century viewed Shaka as a monstrous savage and later African nationalist historians saw him as a revolutionary nation-builder, the basic history remained the same.

Revisionist historians claimed that the violence and turmoil of early-nineteenth-century southern Africa had not been caused by Shaka but rather by violent colonial intrusion. The Portuguese at Delagoa Bay and British privateers at Port Natal sponsored slave raiding into the interior. The Griqua, a frontier society of raiders with horses and guns, attacked Africans in the interior and traded captured cattle and slaves to the settlers of the Cape Colony. Along the eastern frontier of the Cape Colony, settlers and British soldiers organized raiding parties to attack the neighboring Xhosa and other groups. African leaders such as Moshoeshoe, Mzilikazi, Shaka, and Faku were responding to the threats and sometimes opportunities brought by these new forces. All of Shaka’s supposed military innovations existed before he had been born, but what he did was create a larger state that could more effectively respond to the new situation.

New evidence, including recorded Zulu oral history, clearly illustrates that the Mpondo of Faku were not the hapless victims of the Zulu and launched their own predatory attacks on smaller groups. The only successful Zulu raid against the Mpondo occurred in the late 1820s when Shaka cooperated with European-led gunmen from Port Natal. The so-called Mfengu were actually Xhosa-speaking captives and collaborators who were taken into the Cape Colony to serve as a steady supply of labor for settler farms. The central part of what is now South Africa had not been depopulated by Shaka but instead was conquered by expansionist Boers who would later claim it as a promised land given to them by God. Earlier colonial historians had created the myth of the wars of Shaka in order to blame inequity of land ownership on so-called black-on-black violence rather than on colonial dispossession.

Some historians claim that this revisionist theory removes African initiative from history and places too much emphasis on colonial actions. There are questions about exactly when the Portuguese slave trade started at Delagoa Bay and if it was early enough to have caused these events. There has been considerable objection to the accusation that missionaries, in the age of abolitionism, played a role in colonial labor raiding.

Bibliography Etherington, Norman. The Great Treks: The Trans formation of Southern Africa, 1815-1854. New York: Pearson, 2001. Hamilton, Carolyn. Terrific Majesty: The Powers of Shaka Zulu and the Limits of Historical Invention. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1998. Hamilton, Carolyn, ed. The Mfecane Aftermath: Re constructive Debates in Southern African History. Johannesburg: Witwatersrand University Press, 1995. Omer-Cooper, John. The Zulu Aftermath. London: Longmans, 1966. Wylie, Dan. Savage Delight: White Myths of Shaka. Pietermaritzburg: University of Natal Press, 2001.