In other words, although we seem after 1086 to find a classic system of landholding in which tenants hold land from barons and barons hold from the King, all owing military service rather than money and all bound together in a feudal ‘pyramid’ with the King at its top and a broad array of knights at its base, this classical formulation had very little to do with the way that armies were actually raised, even as early as the 1090s. Money rents were already a factor in landholding, and what appear to be military units of land are often best regarded as simple fiscal responsibilities. William the Conqueror paid mercenaries to accompany him to England in 1066, and a mercenary or paid element made up a large element of the professional side of the King’s army ever after. Knights’ fees go entirely unmentioned in the Domesday survey, and the very first reference to the emergence of fixed quotas of knights owed by each of the major tenants-in-chief, in a writ supposedly sent by William I to the abbot of Evesham, occurs in what is almost certainly a later forgery concocted long after the events which it purports to describe.

In reality, we have no very clear evidence for the emergence of this quota system until the reign of Henry II, after 1154. We may assume its existence at an earlier date, not least because by 1135 it appears that the majority of the greater barons expected to answer for round numbers of knights, generally measured in units of ten, answering for twenty, fifty or sixty knights. That such quotas ever served in the field, however, or that they were used as the basis for levying taxation on barons who did not themselves serve, remains unproved until the 1150s. One scenario, rather likelier than the traditional presentation of such things, is that barons and the greater churchmen answered for fixed numbers of knights to the King, and were responsible for ensuring that a certain number of men turned up in their retinues whenever summoned, if necessary by paying mercenaries to make up their ‘quotas’. This would explain why lists of such ‘quotas’ begin to appear in monastic records, for example at Canterbury by the 1090s and why the King had cause to complain, again at Canterbury in the 1090s, not of the quantity but of the poor quality of the knight service that was being supplied. Only at a later date, and only really with nationwide effect from the 1150s, did kings begin to charge a tax (known as ‘scutage’ or ‘shield money’) on barons who failed to supply the requisite quota of knights, arranging for this money to be paid to fully professional mercenary soldiers rather than have the baron make up his service by paying any old rag-tag or bobtail retainer.

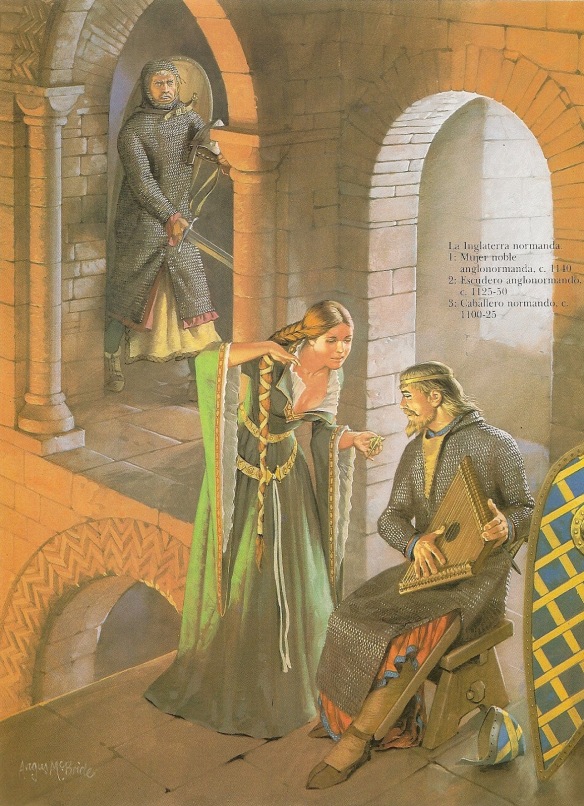

The classic formulation of the ‘feudal’ pyramid ignores other inconvenient or untidy aspects of reality. With the barons holding from the king, and knights holding from barons, it was clearly necessary for the barons themselves to recruit large numbers of knights. To begin with, in the immediate aftermath of the conquest, such knights were often drawn from the tenantry who in Normandy already served a particular baron. Thus knights with close links to the Montgomery family in Normandy naturally gravitated to the estates of the Montgomeries in Shropshire (amongst them, the father of the chronicler Orderic Vitalis, which explains Orderic’s later move from Shropshire back to St-Evroult and the Montgomery heartlands in southern Normandy). Those Bretons who distinguished themselves in England after 1066, such as the ancestors of the Vere family in Essex, future earls of Oxford, or the future earls of Richmond in Yorkshire and East Anglia, tended to recruit other lesser Bretons into their service. The honour of Boulogne carved out in England, especially in Essex after 1066, recruited large numbers of knights originally associated with the northernmost parts of France or southern Flanders. It has been argued that the consequence here was the emergence of a series of power blocks based upon pre-existing French loyalties. The Bretons stuck together. Normans from the valley of the river Seine tended to stand apart from those from lower Normandy and the Cotentin peninsula. Such may have been the case for a generation or so after 1066. Surveying the rebels of 1075 who had joined the Breton Ralph, Earl of East Anglia in rising against the king, Archbishop Lanfranc was able to describe them collectively as ‘Breton turds’. What is more significant, however, is that such regional identities very swiftly began to break down in the melting pot of post-Conquest England. Normans consorted with Bretons, Bretons married English or Norman wives. By the reign of Henry I, after 1100, it is clear that, within England, those of diverse Norman and Breton background fought together or, on occasion, on opposing sides, without any clear pattern imposed by pre-existing regional loyalties in northern France. Why was this so?

The most obvious answer lies in a shortage of appropriate manpower after 1066. The King had to ensure that those to whom he gave great estates were both loyal and competent. Hence, for example, the extraordinary way in which Roger of Montgomery was promoted not only to command two of the rapes of Sussex, Arundel and Chichester, in the front-line of defence against attack by sea, but also to a vast estate in Shropshire, on the Welsh Marches, clearly in reward for past service but carrying with it future responsibility for the defence of yet another strategically vital frontier. Roger, accustomed to the frontier fighting of southern Normandy, was chosen to fill the shoes of three men presumably because he was one of the few men whom the King could trust. If loyal commanders were few and far between at the upper end of society, then lower down, too, it was hard to find the competent knights that any great lord would be anxious to attract to his service. In the rebel-infested regions of the fens, within the estates of the monks of Ely and Peterborough, where the English had several times mounted armed resistance after 1066, a deliberate attempt seems to have been made to swamp the countryside with Norman knights. Enormous numbers of small estates were carved out, burdened with knight service and handed over to practically all comers from northern France. A similar and deliberate mass importation of outsiders might explain why the West Country, yet another forum of rebellion, was colonized by knights, many of them from the frontier regions of south-west Normandy, granted in England the so-called ‘fees of Mortain’, held from their overlord, William the Conqueror’s half-brother, Count Robert of Mortain, and possessing the value of only two-thirds of an ordinary knight’s fee elsewhere in the country.

These lesser knights of eastern and south-western England, probably from the very start, lacked the landed resources ever to serve effectively on campaign. It was their sheer quantity rather than their particular competence which won them their English land. As this suggests, there was never a shortage of land-hungry knights, younger sons, ambitious outsiders or thrusting members of the lower ranks. As a simple commodity, knights were, if not quite ten a penny, then certainly bred up in enormous numbers within eleventh-century society. A treaty between England and the Count of Flanders, first negotiated in 1101 and thereafter renewed on a regular basis throughout the next seventy years, provided for the King of England to pay an annual subsidy to Flanders in return for a promise of the service of no less than 1,000 Flemish knights, should he require it. Figures for the total number of knights settled in England by the thirteenth century vary between a parsimonious 1,200 and a profligate 3,000. Of such men, however, relatively few would have been any use in a fight.

As today, the obligation to pay taxes, which in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries were used chiefly to support the King’s military endeavours, does not imply any ability on behalf of the taxpayer to discharge the functions for which such taxes pay. We may grumble about our taxes paying for tanks and guns, but we ourselves would not know one end of a bazooka from the other. Even the equipment necessary for fighting – a mail coat, a sword and shield, a helmet and, in particular, the expensive war horse that the Bayeux Tapestry depicts carrying the Normans into battle, a sleek and priapi-cally masculine creature – all of this lay beyond the means of a large number of those who in technical terms appear in England after 1100 described as knights. In a society organized for war, founded upon war, and with war as its chief sport and future ambition, the professional players could be attracted only at a very considerable premium.

Landholding and Loyalty

Hence the fact that, by the 1080s, we find so many of these ‘real’ knights holding land from large numbers of Norman lords, all of whom were keen to attract the very best of subtenants. If we take just a couple of examples from the Domesday survey, we might begin with a man named William Belet, literally ‘William the weasel’. By 1086, William, whose nickname is clearly French and probably Norman, held the manor of Woodcott in Hampshire, a substantial estate at Windsor in Berkshire and several Dorset manors, all of them directly as a tenant-in-chief of the crown. In addition to these tenancies-in-chief, however, William had also acquired at least one subtenancy in Dorset from the major baron, William of Eu, principal lord of the Pays de Caux, north of Rouen, in which the Belet family lands in Normandy almost certainly lay. In turn, since William Belet’s heirs are later to be found as tenants of several other manors held from the descendants of William of Eu, William Belet can almost certainly be identified with an otherwise mysterious William, without surname, who at the time of Domesday held most of William of Eu’s Dorset estate as an undertenant. Furthermore, by the 1190s, the Belet family is recorded in possession of the manor of Knighton House in Dorset, held at the time of Domesday from another baron, King William’s half-brother the Count of Mortain by another mysterious William, again almost certainly to be identified as our William Belet.

In this way, with a little detective work, we can very rapidly put together a picture of a Domesday Norman knight who held from at least three lords, including the King, and whose heirs were to remain a considerable force both in local and national politics for two hundred years thereafter. Rising at the court of the Conqueror’s son, King Henry I, William Belet’s son or grandson, Robert Belet, acquired the manor of Sheen in Surrey for service as the King’s butler. As a result, the Belets became hereditary royal butlers, responsible for the procurement and service of the king’s wine, the Paul Burrells of their day. Michael Belet, a leading figure at the court of Henry II, is shown on his seal enthroned on a wine barrel with a knife or bill hook in both hands, testimony both to his proud office and to his close access to the royal court. His seal, indeed, can be read as a deliberate mockery of the King’s own seal on which the royal majesty was displayed enthroned, carrying the orb and sceptre in either hand. Michael Belet and his sons were a major presence at the courts both of King Henry II and King John, founders of Wroxton Priory in Oxfordshire, later the residence of that least successful of British prime ministers, Lord North, of American Independence fame. Yet even by the 1180s, the Belet family was quite incapable of personal military service to the King. Michael Belet, the butler, was a courtier, a King’s justice and lawyer, not a warrior. The family estates in Dorset had by this time been so divided and dispersed amongst several generations of brothers, sisters and cousins, that the Dorset Belets were merging into the ranks of the free peasantry.

To see how common a pattern this is, let us take another example, again more or less at random. In Domesday, we find a knight named Walter Hose, literally Walter ‘Stockings’ or Walter ‘the Socks’, tenant of the bishop of Bath for the manors of Wilmington and Batheaston in Somerset, and holding land in Whatley of the abbots of Glastonbury. In 1086, Walter was also serving as farmer of the royal borough of Malmesbury, paying an annual render of £8 to the King, probably already as the King’s sheriff for Wiltshire, an office which he held until at least 1110. A close kinsman, William Hose, held other lands in Domesday of at least two barons, the bishop of Bath and Humphrey, the King’s chamberlain. The Hose family remained a major force in Wiltshire politics thereafter. Henry Hose or Hussey is to be found fighting in the civil war of the 1140s, in the process acquiring a castle at Stapleford in Wiltshire and establishing a cadet branch of his family at Harting in Sussex. One of these Sussex Hoses returned to Wiltshire after 1200, joined the household of William Marshal, Earl of Pembroke, and fought in Marshal’s wars, acquiring a major Irish estate in the process. As a result, the chief Hose or Hussey fortunes were transferred to Ireland. The family in England remained, like the Dorset Belets, as a reminder of vanished glories, not without resources and not without land, but no longer at the cutting edge of the military machine.

What do such stories teach? To begin with, they should remind us that competence has always been a rare quality, and that the able and the talented, in this case knights, can command a high price for their services. From the very start, however, there would be a problem with any model of ‘feudal’ society that attempted to assign either the Belets or the Hoses to a particular rank or position within society. Both families began with knights, but knights who held both from the King and from other lords. We can assume that William Belet was a wealthy man, with estates scattered across at least three English counties, one of the premier league players in the game of Norman conquest. Walter Hose was the King’s sheriff for Wiltshire, one of the leading figures in local administration. Yet neither of these men, if rather more than mere knights, were barons. Moreover, even by the 1080s, their loyalty to the lords who had rewarded them was very far from clear. If the Count of Mortain should rebel against the King, in the case of William Belet, or if the bishop of Bath should seek to seize land from the abbot of Glastonbury, in the case of Walter Hose, which lord would William or Walter support?

At least William and Walter were fighting men whose support was worth purchasing, but what of their sons and grandsons? The hereditary principle ensures that, once a landed family becomes established, it is relatively hard to divide it from its land or wealth. But this is no guarantee that the children of such a family will continue to dream of battle and the clash of arms rather than the pleasures of the wine cellar, the counting and spending of their money, or, dread thought, such ignoble pursuits as farming, reading and even writing. Military ability or general intelligence, unlike wealth, cannot be guaranteed by inheritance. Loyalty is most certainly not a genetically transmitted trait. Just because a family ancestor was loyal to the Count of Mortain or the Bishop of Bath, this is no guarantee that the children or grandchildren of such a man would remain loyal to future counts of Mortain or bishops of Bath in the years, indeed centuries, yet to come. The great, the kings and counts, earls and bishops of this world, have always had to repurchase the loyalty of their servants and cannot rely upon tradition alone to buy them either brain or muscle.