The whump-whump-whump of the first salvo of NVA rockets woke Jim Bullington from a deep sleep. Bullington listened to the rockets and mortar rounds fall for a few minutes, but none was even close to his guest house in the power plant. Further reflection convinced Bullington that there was nothing he could do to influence events. So, cool war veteran that he was, he drifted back to sleep.

Meanwhile, a short distance to the west of Bullington’s guest cottage, his fiancée—Tuy-Cam—was startled awake by shrieking, crying, and pleading in the darkness outside her parents’ home. One of her three sisters shrieked, “Oh, God! VC!” and rushed into the adjacent bedroom to wake her other two sisters.

In a moment the household was in a turmoil as the family worked together to hide Tuy-Cam’s two brothers, An and Long, who were both home on leave from the service. Quickly the two young men, together with every shred of evidence that might give away their presence, were shoved into the attic. An and Long barricaded the door from within.

Outside the house, VC and NVA were running through the neighborhood, their boots thudding on the pavement. Closer to home, two refugees Tuy-Cam’s grandmother had allowed to camp in the backyard were questioned by several VC and then led away. Everyone in the house slipped into the family’s bombproof bunker. At length, Tuy-Cam’s mother exclaimed, “So, here they are!”

As Tuy-Cam’s mother prayed, the sounds of detonations and gunfire continued.

#

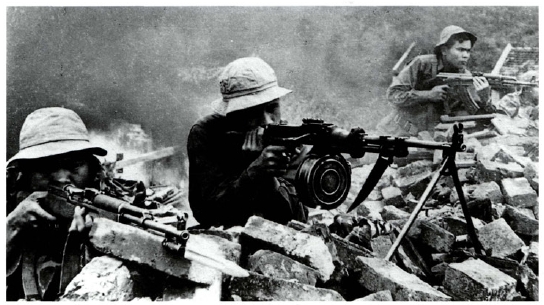

At the first flash of the first salvo of incoming rockets, Comrade Thanh and his three companions opened fire and threw grenades into the guard post at the Chanh Tay Gate. Several of the stunned civil guardsmen who stood at the base of the Citadel wall were mowed down. Others turned and fled. Realizing they were under attack, ARVN soldiers patrolling the bridge across the Citadel moat pulled a few strands of barbed wire across the roadway. They were immediately pinned down by fire from Comrade Thanh’s team.

At that moment one of Thanh’s men signaled with a flashlight, and the 800th NVA Battalion regulars waiting outside the Chanh Tay Gate poured into the Citadel. The soldiers swept over the ARVN bridge guards and the surviving civil guardsmen. The NVA soldiers and Thanh’s men exchanged revolutionary slogans as the 800th Battalion fanned out to seize objectives throughout the western Citadel.

#

The forty handpicked NVA sappers assigned the task of infiltrating the 1st ARVN Division CP compound via the water gate were thwarted when they discovered that the gate bridge had collapsed into the moat and had been replaced by a stout barbed-wire barrier. After milling about for several crucial minutes, the sappers and an accompanying company of the 802nd NVA Battalion felt their way south-westward along the Citadel’s north-western wall. Finally, under cover of mortar rounds fired from the south, they launched an unrehearsed attack on the ARVN post guarding the Hau Gate. The four guard bunkers were quickly overrun, but the element of surprise had been lost. The spearhead force barely cleared the Hau Gate in time to link up with the balance of the 802nd NVA Battalion, which was driving eastward along the north-western wall from the An Hoa Gate.

Under cover of nearly a hundred 82mm mortar rounds, the combined NVA assault force pushed a dozen ARVN soldiers out of their post on the southwestern side of the 1st ARVN Division’s CP compound, but other ARVN troops were attracted instantly by the sounds of gunfire. As the NVA crossed the compound’s southwestern wall and attacked the ARVN division’s medical center, Lieutenant Nguyen Ai, an ARVN intelligence officer, counterattacked at the head of a scratch platoon of thirty ARVN clerks, medics, and several hospital patients.

Only sixty feet from the NVA’s forwardmost element, Brigadier General Ngo Quang Truong looked up from his desk in time to see his aide, at the window, empty his pistol at the attackers. Truong wondered whether he, a brigadier general, would be leading infantry before the night was over. He quickly forced himself back to the business of running his entire division while his troops held the enemy at bay.

Lieutenant Ai was shot through the shoulder, but he continued to lead the counterattack in the medical center. Within minutes five NVA soldiers were shot to death inside the compound and another forty were mowed down as the vastly superior but profoundly shocked NVA. force pulled back to the west.

A subsidiary attack, possibly incorporating some VC units, moved on the CP’s main gate, in the compound’s south wall. The attack drew immediate defensive fire, and an ad hoc reaction force stopped the attackers cold.

#

A second serious setback was dealt to the 6th NVA Regiment at 0400, as a company each from the 800th NVA and 12th NVA Sapper battalions were converging to seize Tay Loc Airfield. An unreported wire barrier forced the NVA units to diverge from their direct route onto the runway. At 0350, as the force sought a way around the barrier, it ran smack into a depot manned by the 1st ARVN Ordnance Company, which conducted a spirited defense of its small compound and forced the NVA soldiers to recoil. Though the NVA companies succeeded in setting fire to an ammunition warehouse, fuel tanks, and quarters, they could not force their way through the ARVN ordnancemen. At 0400, as the NVA. companies were trying to muster a flanking push across the runway itself, Captain Tran Ngoc Hue’s 250-man ARVN Hoc Bao Company swept in from the east in the nick of time. The skilled Hoc Bao troopers fired their rifles and volleys of M-72 LAAW antitank rockets directly into the leading NVA files just as the NVA soldiers reached the center of the runway. The shocked NVA soldiers quickly retreated and called for help. Another company of the 800th NVA Battalion was diverted from its objectives east of the Chanh Tay Gate, but it arrived too late to have any impact. Several buildings in the airfield complex remained in NVA hands, but the NVA offensive in the north-western Citadel was effectively blocked.

As soon as the pressure on the airfield appeared to lift, Captain Hue led his Hoc Bao troops in a long, curving path back to the 1st ARVN Division compound. The stymied NVA apparently never knew that the Hoc Bao soldiers had gone, for they did not renew their attempts to capture the airfield or the ordnance depot.

With the return of the Hoc Bao Company, the 1st ARVN Division headquarters units were able to launch an effective counterattack that drove the 802nd NVA Battalion completely out of the division CP compound. Thus, in the northwestern half of the Citadel, there remained two widely separated ARVN enclaves manned by less than 600 ARVN soldiers, most of whom were noncombatants. Directly facing them were the complete 802nd NVA Battalion, part of the 800th NVA Battalion, and most of the 12th NVA Sapper Battalion—in all, an enemy force numbering as many as 700 crack combatants.

Awakened suddenly from a deep sleep, Marine Major Frank Breth, the 3rd Marine Division liaison officer to the 1st ARVN Division, counted three distinct rocket detonations outside the MACV Compound. Then, as Breth was shrugging into his war belt and grabbing his M-16 rifle, the fourth 122mm rocket blew up the province advisor’s house, inside the compound itself, right behind Breth’s room. As Breth sought shelter in the tiny shower stall in his room, another 122mm rocket hit a nearby jeep; its gas tank exploded. The roof over Major Breth’s head fell right in on him. As a company commander and infantry battalion staff officer along the DMZ throughout the latter half of 1967, Breth had endured countless rocket attacks. This time, he thought he was dead. It took precious moments for him to figure out he was okay. His worst wound was a gouge in the head, a throbbing inconvenience he decided to ignore.

Though thoroughly taken in by the NVA surprise mortar and rocket attack, Colonel George Adkisson’s MACV advisors and headquarters troops reacted superbly to the first detonations inside their compound. Provided with an incredible five-minute respite between the end of the bombardment and the onset of the 804th NVA Battalion’s planned sapper-and-infantry assault, the officers and men who had been assigned to defensive positions in bunkers and guard towers throughout the compound leaped to action, as did many volunteers. Everyone else headed for shelters to await the outcome or orders from above.

The shelling had a negligible effect, and the first of the NVA assaults against the compound gate and various points around the outer wall facing Highway 1 ran directly into vigorous defensive fire. The main assault, on the main gate, ran smack into the fire of three specially trained Marine security guards who had been sent to Hue several months earlier by the U.S. embassy in Saigon. The Marines were on post in a bunker at the southwest corner of the compound before the initial bombardment ended— ready, willing, and able to blunt the NVA attack coming straight up Highway 1 from the south.

Another key factor in the defense was an M-60 machine-gun post in a tower overlooking all the approaches to the compound. The M-60 gunner, Specialist 4th Class Frank Doezma, was the first to fire at the NVA main assault group, and he temporarily stopped the attackers dead in their tracks. The NVA reacted by firing a B-40 rocket-propelled grenade (RPG) into the six-meter-high tower. The M-60 was knocked out and Doezma’s legs were shredded in the blast. The first man to reach the smoking tower was Marine Captain Jim Coolican, who was off duty that night from his advisory job with the Hoc Bao Company. Doezma was Coolican’s regular jeep driver. As soon as Coolican deposited Doezma on the ground, he climbed back into the tower to slam 40mm high-explosive grenades at the NVA with the M-79 grenade launcher he had looted from the open MACV armory.

By the time Coolican opened fire, Major Frank Breth had climbed onto the roof of the main building. From there he looked out on a scene of total chaos—people yelling, gunfire and detonations, a maelstrom of noise and confusion. As the veteran Marine major tried to shut out the noise and look for clear targets, he saw the remnant of an NVA sapper platoon moving north along Highway 1, directly toward the compound’s front gate. As they approached, many of the NVA were cut down, principally by the three Marine security guards and Captain Jim Coolican. However, about fifteen of the enemy kept on coming.

The Marines manning the southwest guard post shot down about half of the remaining NVA, but one of the NVA stuffed a grenade into the bunker’s firing aperture, killing all three Marines. Taking careful aim at a figure carrying what seemed to be a satchel charge, Major Breth fired his M-16 and dropped him to the ground. But other NVA quickly followed. Breth continued to fire his M-16 on full automatic. Then it seemed like everyone was yelling, “Shoot! Shoot! They’re coming down the road! Shoot!” Breth and another Marine major began hurling grenades from the roof, right down on the NVA survivors. The NVA turned and ran. The assault on the front gate of the MACV Compound was over.

The NVA platoon had little room in which to maneuver, and all their routes of attack were obvious and easy to seal off. After a series of futile attacks on the eastern and southern compound walls, the 804th NVA Battalion backed off. From then on, the greatest danger the Americans inside MACV faced was from the wild shooting of the thoroughly panicked men in the adjacent central station of the GVN National Police. In fact, an Australian Army advisor was probably killed by fire from the police station.

As the RPG and small-arms fire directed against MACV died down, the advisors could hear shooting from all around the city, mainly from AK-47s. Hue seemed to be under attack everywhere at once.

#

Elsewhere south of the Perfume, the K4B NVA Battalion appeared to have achieved success in its zone—the triangle formed by the Perfume River to the northwest, Highway 1 to the northeast, and the Phu Cam Canal to the south. At any rate, a large number of isolated civil objectives in that sector were seized, and VC cadres were soon moving in to set up a civil government of their own. However, a small number of thinly manned ARVN posts on the south bank of the Perfume could not be taken by the widely dispersed K4B NVA Battalion, and, strangely, a number of small, isolated ARVN camps and facilities in its zone were left undisturbed throughout the night.

The Communists later claimed that all three assault battalions in the 4th NVA Regiment zone, south of the Perfume River, were in position to attack their objectives in advance of the initial rocket volley. They even claimed that the K4C NVA Battalion and an attached sapper unit—the force that had been pinpointed, bombarded, and delayed by artillery fire on the afternoon of January 29—had completed a forced march from the Ta Trach ferry sites during the evening of January 30. However, the K4C NVA Battalion’s main objective, the cantonment of the 7th ARVN Armored Cavalry Battalion, was not seriously molested during the night. Certainly it was not attacked by the reinforced K4C NVA Battalion.

No Communist unit attacked the 1st ARVN Engineer Battalion compound, on the southern edge of the city, nor the U.S. Navy’s Hue LCU ramp, on the Perfume River. If, as they later claimed, the Communists reduced all the civil targets on their long list of objectives, they nevertheless did a spotty job of reducing military targets.

To the Communists, clearing the military opposition was a means to an end. That end was the civil objectives, because of what they symbolized. The Communists were seeking the general uprising. Ultimately, however, passing up or wasting opportunities to destroy military targets was their undoing.

It is an axiom of night battle that things are never as bad as they seem. Daylight invariably chases away the deepest of fears and the wildest of speculations shared by combatants on both sides. No matter how bad things really are, they are never as bad as they seem to be at night.

Long before dawn offered Hue’s beleaguered defenders the first glimmer of hope, Brigadier General Ngo Quang Truong was at work planning and ordering the relief of the city. Heavy fighting seemed to be raging everywhere in Hue at once, and the reports General Truong was receiving at the 1st ARVN Division CP were vague, often bordering on panic, and thus of little use beyond establishing the scale of the Communist plan. But Truong intuitively grasped what there was to grasp, gathered what information there was to gather, and acted while there was still time to act. Above all, he knew, it was vital to launch some form of counterattack before the Communists reduced all their objectives and consolidated all their gains. Blooded warrior that he was, Truong knew for a certainty that the Communists could not have seized all their objectives without error or setback. He knew from bitter experience that fluid situations tended to work to the advantage of the defender. The sounds of gunfire from all directions and the reports Truong was able to gather on his radio told him the situation remained extremely fluid and that, probably, the Communist timetable was a shambles. Moreover, he quickly learned that he still had the means for knocking the Communist plan further askew and, hopefully, defeating it in short order.

General Truong was quite right. The Communists had only come near to winning a swift victory. But they had failed to do so, and time definitely was not on their side.

The 6th NVA Regiment continued to battle mightily for key objectives within the Citadel, but the situation around General Truong’s CP seemed to have stabilized. Even though Truong’s troops were unable to attack out of the compound, at least the Communists seemed unable to attack into it. On the south bank of the Perfume River, the 4th NVA Regiment appeared to have conceded several key objectives. The MACV Compound was no longer under direct pressure, and the cantonments of the 7th ARVN Armored Cavalry Battalion and the 1st ARVN Engineer Battalion, both on the southern fringe of the south bank of the Perfume, had never been molested at all.

#

Unfortunately for Hue’s defenders, the axiom that dawn imposes reality and presents new opportunities cuts in both directions.

At G hour, the handpicked 3rd Company of the 6th NVA Regiment’s 800th NVA Battalion had made its way from the Huu Gate, on the south-eastern end of the Citadel’s southwestern wall, toward the Ngo Mon Gate, the south-eastern entrance into the Imperial Palace. However, before getting very far, this company had been diverted to help two other NVA companies that were stalled in their bid to overrun Tay Loc Airfield. The 3rd Company did not get back on the track for several hours.

At about 0500, shortly after the Hoc Bao Company was ordered back from Tay Loc Airfield to help defend the 1st ARVN Division CP, General Truong ordered the 1st ARVN Ordnance Company to abandon its depot beside the airfield and withdraw to the 1st ARVN Division CP compound. The way things seemed to be going in the Citadel, conceding the depot and the airfield to the Communists was preferable to losing the ordnance troops or being forced to fritter away assets in rescuing or supporting them. Soon the 800th NVA Battalion renewed its attack on the recently abandoned airfield and secured it without further loss. The NVA soldiers destroyed the light observation airplanes they found parked near the runway and looted the ordnance depot of its stores, including many weapons.

Far behind schedule, the 800th NVA Battalion’s 3rd Company set out again to seize the Imperial Palace and the huge flag platform on the south-eastern wall of the Citadel, opposite the Ngo Mon Gate. However, the company was delayed again by Lieutenant Nguyen Thi Tan’s 1st ARVN Division Reconnaissance Company. Following its evening scouting mission west of the city, the company had infiltrated Citadel streets by way of the 1st ARVN Division CP compound. Lieutenant Tan’s troops, skilled at moving without detection, launched tiny hit-and-run delaying actions against the NVA infantry company. However, at 0600 a platoon of NVA sappers the ARVN scouts apparently did not engage seized the Ngo Mon Gate from an eight-man squad of sentries.

As soon as the Ngo Mon Gate was seized, the main body of the long-delayed 3rd Company side-slipped Lieutenant Tan’s tiny blocking force and poured into the palace compound. It routed or took prisoner all the GVN civil guardsmen and national policemen within. Then, to underscore the deeply symbolic victory, each of the NVA liberators took his turn sitting on the imperial throne.

A platoon from the 800th NVA Battalion’s 3rd Company seized the flag platform in the center of the Citadel’s south-eastern wall at the same moment the Ngo Mon Gate fell. The Communist soldiers swiftly pulled down the gold-and-red GVN flag—the same banner General Truong’s troops had raised the previous morning. For the moment, nothing more was done, but the fact that the GVN flag was not flying was obvious to all who could see the flagpole in the dawn’s early light.