The KUBAN 1943 (The Wehrmacht last stand in the Caucasus). Illustrated by Steve Noon.

In late February and early March 1943, poor weather prevented any significant operations and movements by either side in the Novorossiysk area. Towards the end of March, the northern flank of Seventeenth Army was pulled back slightly to improve its positions in the marshy region along the coast of the Azov Sea. Around this time, Army Group A and Seventeenth Army finalised plans for Operation Neptune, an offensive aimed at destroying the Soviet forces in the Malaya Zemlya beachhead and retaking the area. The offensive was originally planned for 6 April, although this date was not definitively finalised, as clear weather was required to ensure that strong Luftwaffe forces could be used for close support of the attacking troops, suppression of enemy artillery batteries on the coast road between Novorossiysk and Kabardinka on the eastern shore of Tsemess Bay and prevention of reinforcement and supply of the beachhead by sea. Aircraft were transferred from the Donbass and southern Ukraine to reinforce Luftflotte 4’s forces for this effort.

The attacking forces would include:

- 4th Mountain Division: 5 battalions, with 2 mountain artillery battalions, strengthened by additional artillery and army combat engineers.

- 125th Infantry Division: all available forces, including reinforcement by one assault gun battalion and parts of another from army troops. The force was split into two groups, a northern group with 2 battalions and a southern group with 3 battalions.

- 73rd Infantry Division: a specially-formed attack group and all artillery.

In order to achieve maximum surprise, the concentration of 4th Mountain Division and the regrouping of 125th and 73rd Infantry Divisions were to take place at night and in small groups, to be completed by 18:00 on 5 April. Additional deception measures included strict traffic control and radio silence, the dissemination of false rumours about an imminent withdrawal from Novorossiysk and unchanged reconnaissance, combat patrol and artillery activity. The attack was to be launched without a preliminary artillery barrage, and if individual assault groups required artillery support, this would only be launched at the jump-off time.

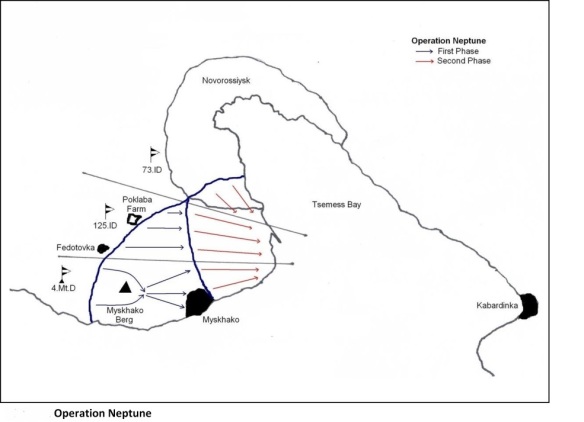

The attack was divided into two phases. In the first phase, 4th Mountain Division and 125th Infantry Division would advance from their concentration areas around Fedotovka and Poklaba Farm, respectively, towards the Myskhako – Stegneyeva Farm road, with 4th Mountain Division taking Myskhako Berg and Myskhako village and 125th Infantry Division clearing the Myskhako Valley and a wooded area to the north of the village. In this first phase, 73rd Infantry Division’s artillery would provide support for the left wing of 125th Infantry Division. Once the first phase had crossed a loop on the Myskhako – Stegneyeva Farm road, 73rd Infantry Division would join in the second phase by attacking south into Stanichka. It was envisaged that the attack would reach so far into the beachhead that the enemy forces would be split into many individual groups that could be destroyed piecemeal. In particular, the army commander General Ruoff stressed the importance of penetrating as far as possible into the beachhead on the first day to prevent the evacuation or reinforcement of the enemy by sea, although he expressly forbade the setting of specific daily goals.

On 1 April, radio intercepts and ground reconnaissance suggested that the Soviets would launch an attack against the east wing of XXXXIV Corps, perhaps as early as the following day. The army’s war diary acknowledges that this could make the situation “uncomfortable,” but concludes that it was not a reason for specific concern. The intended start date of 6 April was postponed due to poor weather, as was the first rescheduled date of 10 April.

The offensive was eventually launched at 06:30 on 17 April, after a final one-hour delay caused by heavy fog that prevented air activity. The 4th Mountain Division’s attack initially broke through the forward positions to the slopes of Myskhako Berg and Teufels Berg, about 1.5 kilometres to the east, but was then held up by strong enemy resistance. The attack by the northern group of 125th Infantry Division was initially focussed on the Myskhako Valley and high ground to the north and northwest of Myskhako village, and a penetration of about one kilometre was forced. Its left wing broke through the forward positions southwest of the road loop and became involved in heavy fighting in an area around one kilometre west and southeast of Stegneyeva Farm.

Despite the importance of suppressing the enemy artillery on the eastern shore of Tsemess Bay, fire from this area resumed in the early afternoon, aimed primarily at the northern wing of 125th Infantry Division. Combat reports confirmed that the enemy had moved significant forces into the front line in anticipation of the attack, and the heavy fighting for strongly-fortified positions caused considerable losses among the attacking infantry.

In the afternoon, in a discussion among Generals Ruoff, Wetzel (V Corps) and Korten (Luftflotte 4), the possibility of transferring parts of 73rd Infantry Division to 125th Infantry Division to boost the latter’s strength at the key breakthrough positions was discussed. This proposal was ultimately rejected because of the time that the regrouping would take and because it was considered that the most favourable force ratios were in 73rd Infantry Division’s sector, as the Soviets had moved significant forces from the southern parts of Novorossiysk to the Myskhako – Stegneyeva area.

During the night of 17 – 18 April, a Soviet convoy that approached the beachhead was brought under artillery fire, and two vessels were reported to have been set on fire. The offensive was renewed at 05:30 on 18 April after harassing fire by all available artillery, but again quickly became bogged down by the tenacious Soviet defence and the difficult terrain and did not achieve a decisive early penetration at any point. During the night, the Soviets had moved up the 83rd Marine Infantry Brigade, one of the units that had originally participated in the Malaya Zemlya landing, from the rear to reinforce the defences in the Myskhako Valley.

During the course of the morning, however, 125th Infantry Division succeeded in breaking through in an area to the southeast of Poklaba Farm and taking the northeastern slope of a small hill about one kilometre north of Myskhako village. The attacks by 73rd Infantry Division and 4th Mountain Division, which had not achieved any significant results in the face of the strong Soviet resistance, were halted to allow additional forces to be thrown against the schwerpunkt north of Myskhako. One regiment was transferred from 6th Romanian Cavalry Division, two regiments from 4th Mountain Division and two battalions, along with mortar and assault gun units, from 73rd Infantry Division.

In spite of poor weather, the first Soviet counter-attacks were launched early on the morning of 19 April, in the area of the road loop, preceded by heavy artillery and mortar fire, and through the day further localised counter-thrusts were launched. On the

German side, the bad weather delayed the redeployment of troops to 125th Infantry Division, but at 11:20 it launched an attack aimed at linking up with a group that had already reached the slopes of Teufels Berg. After seven hours of bitter fighting, the linkup was finally achieved, but the united assault groups were almost immediately put on the defensive by Soviet counter-attacks from the south and east, supported by artillery fire of an unprecedented intensity.

After defending against numerous local Soviet counterattacks through the night of 19 – 20 April, 125th Infantry Division launched another attempt to take the high ground at 10:30, but this was stopped by further fortified Soviet defensive positions after gains of just a few hundred metres. Later in the day, General Jaenecke visited the headquarters of both V Corps and 125th Infantry Division. A review of the operation so far revealed that the air and artillery support had not been able to eliminate the Soviet defensive systems, resulting in high casualties among the attacking German infantry. Although 125th Division was urgently calling for new reserves, an expected Soviet attack on XXXXIV Corps’ sector meant that no forces could be pulled from here to support 125th Division’s attack. It was agreed to postpone further attacks until 22 April, so that new reserves could be created by a regrouping of forces.

On 21 April, there were numerous discussions between army and corps commands about the possibility of resuming the attack. The lack of available infantry forces was a constant theme, with losses since the start of the offensive being estimated at 2,741 men. The Chief of the Army General Staff, General Kurt Zeitzler, requested reports from

125th Infantry and 4th Mountain Divisions in order to present them to Hitler that evening. These reports again maintained that a continuation of the attack would only be possible if fresh forces were made available. Another report to Army Group A noted the declining quality of the divisions as a consequence of the shortage of NCOs and a complete lack of any opportunities for training since early 1942. Another increasing problem for the German command was the situation in the air. In the first few days of the offensive, the Luftwaffe had largely enjoyed air superiority, but by 21 April, aircraft from three newly arriving Soviet air corps were committed, shifting the balance towards the defenders.

On 22 April, V Corps submitted a situation report that concluded that it did not have sufficient forces to continue a concentrated attack against the beachhead, citing the loss of surprise, strengthening enemy air activity and the continuous resupply and reinforcement of the defenders by sea, as well as the lack of its own forces. The total strength of the attacking group was just 13,541 men, out of a combat strength of the whole army of 57,590. Following a visit by Field Marshal von Kleist, the commander-in-chief of Army Group A on 23 April, Operation Neptune was finally called off two days later.

Even accounting for the benefit of hindsight, it appears clear that Operation Neptune was doomed to failure from the outset. The relatively small, worn-out and poorly-trained assault groups faced a numerically superior defending force that had significantly strengthened its positions in the difficult terrain and was able to continually resupply itself by sea. The increasing Soviet air strength over the area increased the pressure on the attacking Germans infantry, both directly and by allowing the Soviet artillery in the beachhead and on the opposite side of Tsemess Bay to play an increasing role. The war diaries of Seventeenth Army and V Corps around this time make an uncharacteristically high number of references to the weakened state of their forces. The growing disconnect between the plans of the German High Command and the forces in the field is graphically illustrated by an entry in Seventeenth Army’s diary for 21 April. It records, perhaps with a hint of sarcasm, a visit by General of Railway Troops Otto Will, who reported on the “grand” plans for the construction of road and railway bridges across the Kerch Strait, with a planned completion date of the railway bridge of 1 August 1944.