It was more like a procession than an invasion. When a large Scottish army passed through Flodden in 1640, their progress was ‘very solemn and sad much after the heavy form showed in funerals’. Trumpeters decked with mourning ribbons led the way, followed by one hundred ministers and, in their midst, the Bible ‘covered with a mourning cover’. Behind the ministers came old men with petitions in their hands along with the military commanders, also wearing black ribbons or ‘some sign of mourning’. Finally came the soldiers, trailing pikes tied with black ribbons, accompanied by drummers ‘beating a sad march such as they say is used in the funerals of officers of war’.

This was a forceful demonstration about the death of the Bible, a complaint about the fate of the true, scriptural religion in Scotland. The origin of their protest was revulsion at a new Prayer Book, introduced in 1637 and described by the Earl of Montrose as ‘brood of the bowels of the whore of Babel’. ‘[T]he life of the gospel [had been] stolen away by enforcing on the kirk a dead service book’, he said. Here was its funeral. In fact the army was not, strictly speaking, the army of the Scots but of the Covenanters, men who had entered a mutual bond before God to defend the true religion. Even at this stage there were Scots who were not Covenanters, and that distinction was to become extremely significant in the coming years – Montrose, for one, was later to abandon this version of the cause and become the champion of armed royalism in Scotland.

This was not the first time that a Scottish army had taken this road, inland from the fortified town of Berwick and crossing the river Tweed, which marks the border between England and Scotland at its eastern end, just south of Coldstream. The last time, in 1513, it had ended in disaster: perhaps 5,000 Scots died, among them the Scottish king, eleven earls, fifteen lords, three bishops and much of the rest of Scotland’s governing class. Fear of the arrival of armed Scots in the north had caused centuries of concern in England. Indeed tenants in the Borders had enjoyed unusual freedoms in return for an obligation to offer armed resistance to Scottish incursions, and the prevalence of cross-border cattle raiding had given rise to something like clan society. When James VI of Scotland ascended to the English throne in 1603, the Borders had, in his vision, become middle shires, and the problems had receded somewhat. Nonetheless, armed Scots were not regarded with equanimity in northern England.

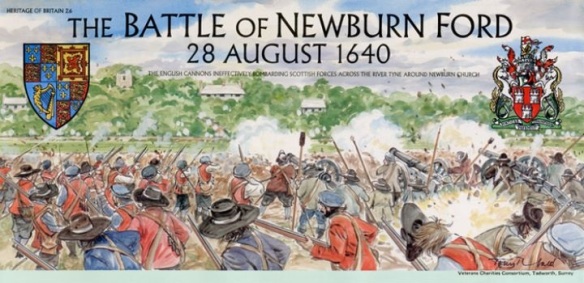

This time, however, they were barely opposed and the march past Flodden was the prelude to a successful occupation of northern England, achieved more or less without a fight. Alexander Leslie’s Covenanting army were faced by 10,000 English troops with more in reserve further south. But this English force was easily discouraged. At Newburn on 28 August, just over a week after they had crossed the border, a short action saw the English routed and on 30 August the Scottish army marched unopposed into Newcastle, one of the nation’s most significant cities.

This, then, was a very peculiar occupation: many Englishmen seem to have felt that the Scots had right on their side, or at least that the English army did not. When they reached Heddon-on-the-Wall, one of the invaders later recalled, ‘old mistress Finnick came out and met us, and burst out and said, “And is it not so, that Jesus Christ will not come to England for reforming abuses, but with an army of 22,000 men at his back?”’ Certainly English forces, locally and nationally, were half-hearted in their responses. The Scottish party had actively courted, and clearly expected to receive, the sympathy of local people, and they were not disappointed.

England and Scotland were separate kingdoms under the same king – their churches, law, administration and representative institutions remained distinct. Like his father, who had first possessed the two crowns together, Charles governed Scotland from London, but he now hastened north. He intended to ‘contain the Northern Counties at his devotion’, fearing, it was said, that local people might ‘waver’ in their support for him. Opinion there had apparently been ‘empoisoned by the pestilent declaration cast among them’ by the Covenanters. In their propaganda campaign of the summer of 1640, in print and in circulating manuscripts, the Covenanters had made it clear that they had no quarrel with England but were forced to take these actions in order to defend their religion and liberties. Some of their papers and publications went further, suggesting that they intended to help England to complete its own Reformation, and that they were an instrument of God’s providence in that respect. Charles’s government was palpably anxious about this propaganda effort. Without the ‘awe of his Majesty’s presence’ it was feared that local people might ‘easily be tempted to fall to the Scottish party, or at leastwise, to let them pass through them without resistance or opposition’. It even seemed necessary to issue a proclamation that the Covenanters were ‘Rebels and Traitors’. Only a nervous government would have felt it necessary to say so, or to add: ‘so shall all they be deemed and reported that assist or supply them with money or victual, or shall not with all their might oppose and fight against them’.

These fears about local loyalties were not groundless. The Covenanters had been amazed that Newcastle was surrendered without a fight and within a week or so of arriving had made the town defensible, something the townspeople had neglected to do over the previous summer. Prior to the crossing of the Tweed there had clearly been contacts with highly placed English politicians and the decision to invade had involved a careful calculation about the effect of crossing onto English soil on English sympathies.

Although this episode is often described as a Scottish invasion it is better understood as a forceful demonstration of grievances by the Covenanters appealing to potential sympathizers in England. The royal proclamation had tried to obscure that distinction, but this was a religious protest intended to make common cause with fellow travellers in one of Charles’s other kingdoms. It enjoyed some success in that respect and there are persistent suspicions about active collusion. Certainly a willingness to accept that the Covenanters were rebels (rather than, say, loyal petitioners with right on their side) became something of a political litmus test in England. Reformation politics did not necessarily respect national borders or dynastic loyalties.