Officers of the 11th Hussars in a Morris CS9 armoured car use a parasol to give shade while out patrolling on the Libyan frontier, 26 July 1940.

On 10 June 1940 Italy declared war on the United Kingdom. As soon as they heard the news the three Commanders-in-Chief set in motion their plans for striking the enemy. Disparity of strengths was great. Wavell had some 36,000 men in Egypt, but they were neither properly organized nor equipped. 7th Armoured Division had only four regiments of tanks; 4th Indian Division was short of a brigade and of artillery; the New Zealand Division amounted only to a brigade group. In Palestine were 27,500 troops but of these only one British brigade and two battalions were equipped and trained; in any case these units were earmarked either for duty in Iraq or for internal security in Palestine. East Africa was even more lightly garrisoned–a British brigade in the Sudan, two East African brigades in Kenya, and a mere 1,500 local troops in British Somaliland. Against this, and bearing in mind that the fall of France removed the threat from Tunisia and Algeria altogether, Marshal Graziani had about a quarter of a million men in Cyrenaica and Tripolitania, whilst in Italian East Africa the Duke of Aosta commanded a total, white and native, of nearly 300,000 soldiers. As we shall see it was not numbers which worried Wavell. What he lacked was fully trained, properly organized and equipped formations. Without these, battles could not be fought.

Nevertheless on 8 June 1940 General Richard O’Connor took command of all forces in the Western Desert. Wavell had already given orders that offensive action against the Italians at the frontier with Egypt would be taken immediately war was declared, so that Western Desert Force was in action three days after receiving its new commander. O’Connor, who had commanded a brigade on the North West Frontier and had also been in action recently against Arab rebels in Palestine, enjoyed a reputation for originality and boldness. He was certainly to live up to it. He would not have been able to do so, however, had Wavell long before not established the logistic foundations which were indispensable to military operations of any sort. Wavell had always maintained that administration and logistics were the most difficult and yet most necessary accomplishments of generalship. The battle for North Africa, as we have already noted and will see confirmed, was a battle of supplies. If Wavell had done nothing else, his place in this battle would have been assured by the steps he took first to prepare for and then to establish a huge base in Egypt and elsewhere able to withstand the endless demands made on it. The Official History underlines the extent to which he himself made the running :

It was also clear to General Wavell that the land forces in the Middle East would sooner or later have to be appreciably strengthened if their contribution to the war was not to be confined to trying not to lose it. He therefore initiated a preliminary survey for the creation of a base for fifteen divisions–say 300,000 men. This figure was no more than an estimate based on a consideration of possible roles, for by the end of October (1939), when the survey of ports, railways, roads and sites was completed, the long-term policy for the Middle East was still being considered in London.

One of the roles that Wavell foresaw was that of invading Libya and he instructed General Wilson, then Commanding British Troops in Egypt, to prepare plans for it, including the problem of supply in the desert. Early in 1940 the War Cabinet gave instructions that the base organizations in Egypt and Palestine were to be developed. So began the process of building ports, airfields, roads, railways, water storage wells, workshops, depots, petrol stores; then of procuring both raw materials to continue their development and the actual commodities to put in them together with vehicles to move them about. All these preparations meant that, by the time O’Connor took over Western Desert Force, units of 7th Armoured Division positioned near Mersa Matruh were able, although short of vehicles, to operate right up to the frontier with Cyrenaica. They were about to show that Italy’s declaration of war was interpreted by the British as actually meaning the start of hostilities. Almost before some of the Italian soldiers knew they were at war, the 11th Hussars had taken Fort Maddalena and the 7th Hussars had attacked Fort Capuzzo.

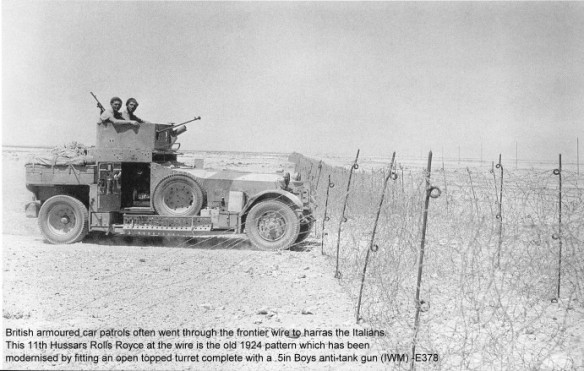

Of all the Desert Rats perhaps the 11th Hussars characterized most completely the troops Churchill had called ‘lean, bronzed, desert-hardened and fully mechanized’. Indeed the regiment had had armoured cars since 1928 and been in the Middle East since 1934. They had been training in the Western Desert for five years and were as experienced in desert lore and navigation as anyone. They would have endorsed the comment on their own regiment made by an Army Cooperation pilot that ‘the British trooper is really marvellous under any conditions; that the desert offers an enchantment unbeknown to anything else; and that, if romance has gone out of the cavalry, there is something equally fascinating in its newly acquired role’. On the night of 11 June the 11th Hussars were engaged in a skirmish which interrupted the desert’s silence for the first time in the three years of shooting which were to follow. Ambushing a column of Italian lorries near Fort Capuzzo, two armoured cars captured some fifty soldiers and seventy weapons, but the squadron did much more than take prisoners. They discovered that the Italians were in no way prepared to start operations against Egypt. O’Connor therefore gave orders on 13 June that Capuzzo and Maddalena would be assaulted.

Armoured cars were not traditionally the sort of troops to use for an assault, but none the less the job of capturing Maddalena was given to a Squadron, 11th Hussars. Next day the squadron set out at 5 am to cross fifty miles of desert to a rendezvous near the fort. There they were to wait until the RAF softened the defences, and on arrival were misled into thinking that this bombing was actually in progress by a rival demonstration of air power–the Regia Aeronautica attacking a former Egyptian Army post nearby. The squadron was lucky not to be spotted by the Italian bombers.

Before long RAF Blenheims appeared, and no sooner had they done so than the enemy bombers made themselves scarce. To the watching Hussars, the Blenheim attack seemed rather puny, but as arranged they ringed the fort with their armoured cars and closed in, expecting a fierce action. Far from having a fight, however, the crews were astonished to see the white flag run up. They rapidly made good the fort’s capture, and all was over by midday.

Later that month the 7th Hussars were engaged in a different sort of battle at Fort Capuzzo after it had been re-occupied by the Italians. Their task was to advance against the enemy artillery batteries, to destroy them and withdraw–almost a Balaclava affair. It says a good deal for what still had to be learned about the proper use of armour, and in particular about cooperation with infantry, that the regiment was invited to attack an enemy defensive position at night without infantry support and with a questionable manoeuvre by which the three squadrons converged from all points of the compass. It was no surprise that the operation, whilst exciting, was not an unqualified success.

The thing began badly. Postponement of the attack meant that it was already too dark when it did get started. The regiment advanced rather slowly and its squadrons were out of position, bunched much too closely together, before they were near enough to the fort to open fire effectively. When they did so, halted only 500 yards away from it, they received a hot rejoinder. Verey lights, multi-coloured tracer, machine guns and, least comforting of all, field guns, apparently on fixed lines, all shot at them. A and C Squadrons, close to these enemy batteries, yet unable to see properly what was happening, were quite helpless to deal with them and had to withdraw. B Squadron, however, attacking from another direction, got quickly across the enemy anti-tank obstacles and into the gun positions. One tank, commanded by Troop sergeant-major Clarke, was hit, then rammed by three enemy tanks, one of whose guns fired point-blank and by some ballistic mystery failed to penetrate even the driver’s glass shield. Then Clarke’s .5 machine gun jammed, a favourite trick of this particular weapon, so he opened up with the .303, wholly ineffective against armour, but which persuaded the enemy tanks to back away and allowed him to reverse too. Again his tank was hit, and this time caught fire. It looked unhealthy, but another tank rushed up and took Clarke and his crew off. Fort Maddalena with an irresolute garrison had been captured with armoured cars by day easily enough, but Fort Capuzzo, defended by Italian gunners, who almost always fought well, was not going to succumb to an uncoordinated attack by tanks at night.

From such modest beginnings grew the battles which were to ebb and flow up and down the desert. Operations like that at Fort Capuzzo and the 11th Hussars’ vigorous patrolling, which resulted in more successful ambushes by themselves and other units of 4th Armoured Brigade, gave these covering troops invaluable knowledge of the frontier areas. The opportunities for bold enterprise were many, and to begin with it was only the British who took them. The desert was something to be used, not feared, and at the end of June General Wavell was to establish an irregular force which made remarkable use of it–the Long Range Desert Group, whose principal tasks were to gather intelligence and harass the enemy. They went on doing so until all North Africa was in Allied hands. But whilst the British might have seized the initiative at the very opening of the campaign, they could not prevent the Italian Army from concentrating its strength between Bardia and Tobruk as a first step to an offensive which everyone expected to be mounted before long.

What was it like to be in the desert behind enemy lines during this period of relative inactivity before the Italian advance got under way?

For the 11th Hussars, keeping their constant vigil, noting every Italian move and change in deployment, getting to know the desert better and better, the days went by in slow time. Just before dawn the patrols would go out, whilst those at squadron headquarters settled down to cook their breakfast. Each armoured car was its own storehouse and own kitchen, and those who have served in regiments of the Royal Armoured Corps will no doubt have observed that the squadron leader’s driver was generally the best cook in the squadron. Wonders could be done with a few eggs and some bully beef. In the heat of the morning while the car commanders on patrol searched through their binoculars, the squadron leader would get his administrative work done, walk round the troops in reserve, and keep an eye open for enemy aircraft. It was easy enough to keep armoured cars and men hidden under camel thorn and camouflage nets provided they kept still. But to move about was to be spotted. Every half hour the watching patrols would report, and if it were, as it so often was, a negative report, the midday meal would come as a welcome break to the endless waiting, however tired men might be of hard-tack biscuits, tinned cheese and bully. With air and ground sentries posted, the afternoon was a good time to sleep, for too much of the night was needed for other things. Perhaps at tea-time there would be a hot bully stew, tea, of course, and some sausages. The BBC overseas service would give them the latest news, and even about the very desert activities they were engaged in, its emphasis or purpose could sometimes come as a surprise to them.

A glass of whisky and water was an agreeable prelude to packing up before moving back to a new position for the night. To this position would come all the troops which had been on patrol and they would be joined there by the transport echelons carrying petrol, rations, letters from home, and, if needed, ammunition. Then the bedding would be unrolled, and again with sentries posted the squadron would sleep. Fifty miles inside enemy territory, they could never relax; choosing where to spend the night was an important matter. Ambushes were all too easy to set. Before first light out the patrols would go again, squadron headquarters motored off to one more piece of desert, and yet another long day full of nothing but waiting, monotony, routine, would have begun.

Long and monotonous the days may have been, but they were not wasted, for when the time came that it mattered the 11th Hussars’ familiarity with the desert was unrivalled and their reconnaissance record unequalled. Time, in any event, was not on the Italians’ side.

#

On the afternoon of 7th May1943, the leading armoured cars of 6th and 7th Armoured Divisions, the Derbyshire Yeomanry and 11th Hussars reached the centre of Tunis. It was fitting that the 11th Hussars, who had begun the battle for North Africa, should be in at the kill.