Manstein, meanwhile, believed that, although his offensive had fallen considerably behind Zitadelle’s timetable, at last he was about to rend the Soviet defences asunder. ‘The prospects for a breakthrough remain good,’ the field marshal explained to Model on the night of the 8th. ‘We must not fail to ensure that we give the enemy’s defences no time to settle and yet retain the power to exploit our successes.’ However, Hoth was concerned by intelligence that ‘considerable Soviet armoured forces’ were massing on his right flank, and Knobelsdorff ’s sources were telling him of the danger posed by the 6th Tank Corps on his left. The offensive could not continue without taking these threats into consideration. During the evening of 8 July, therefore, Manstein, Hoth, Hausser, Knobelsdorff and Kempf were locked in discussion about how to proceed. Although the Germans were making ground in the south, they were doing so slowly and suffering considerable losses in the process. In such circumstances, it would have been extremely beneficial to Zitadelle had the Ninth Army been powering through Rokossovsky’s defences in the northern sector of the salient.

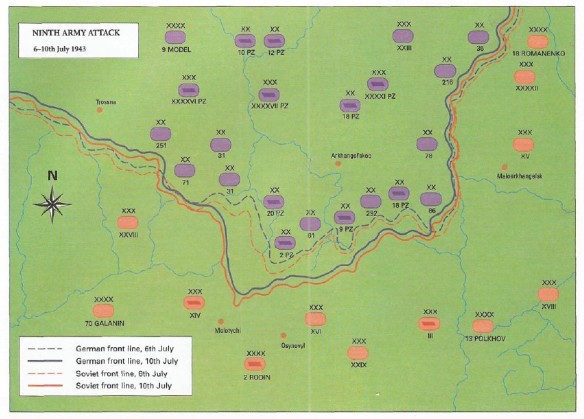

Model’s advance had not been dramatic on the first day of the offensive, but the infantry-based attack had made progress towards the second line of defences. It was on these positions, stretching from Samodurovka to Ponyri and protecting the Olkhovatka heights, that XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps would focus their attention for the rest of the operation. However, 6 July began with a Central Front counterattack. Rokossovsky, while completing the reinforcement of his defences, which included two rifle corps and the 2nd Tank Army, unleashed 16th Tank Corps. Directed against the 20th Panzer Division in the area of the greatest German penetration, 100 T-34s and T-70s struck at 0130 hours. Within four hours, the thrust – which had been strengthened by 17th Guards Rifle Division – had developed into a major confrontation between Soborovka and Samodurovka. Taking advantage of the greater freedom over the battlefield that came with the mounting calls on the Luftwaffe’s rapidly diminishing resources, the reinforced Red Air Force flew in close support. General Rudenko later explained:

I decided to change the tactics of the strike aircraft. I concluded that it would be more expedient to deal one devastating strike against a large force of enemy troops, so for this end I decided to dispatch our aircraft in massive strength. The idea also was that this massing of our aircraft would suppress the enemy’s air defence and thus reduce our own losses.

Il-2s arrived in squadrons of eight and, having circled over the panzers and selected a target, took it in turns to dive down. They aimed at the rear end of their targets with bombs, rockets and cannon. Although it was beyond the Red Air Force to win air supremacy immediately, on just the second day of Zitadelle, it began to out-muscle the Luftwaffe, which gradually lost its aerial dominance. Although the Soviet air arm was not destined to be ‘the decisive battle-winning instrument its numbers would suggest it should have become’, Rudenko commented on the strikes that morning:

The impact of their attack was powerful and obviously unexpected by the enemy. Smoke piles rose from his positions – one, two, three, five, ten, fifteen. It emerged from burning Tigers and Panthers. Despite the danger, our soldiers jumped out of the entrenchments, threw their helmets into the air and shouted, ‘Hurrah!’

Although Rokossovsky’s counterattack had run out of steam by midmorning, it had successfully pre-empted Model’s own thrust and allowed the Central Front time to conclude its defensive preparations. As German and Soviet aircraft continued to tangle overhead, General Lemelsen’s XLVII Panzer Corps mounted an assault led by 300 tanks. To the right, pushing on towards Samodurovka, the 20th Panzer Division had now been joined in the offensive by two of the corps’ reserve formations. On the opposite flank, the 9th Panzer Division advanced towards Ponyri Station, while in the centre, the 2nd Panzer Division, led by the 505th Heavy Tank Battalion’s 24 serviceable Tigers, probed towards Olkhovatka against one of the most strongly fortified sections of the main defensive belt. The rumble of hundreds of guns mixed with the shriek of Katyusha and Nebelwerfer batteries in a shocking display of firepower. The battlefield erupted as bombs, shells, rockets and mortars exploded, each with a blinding flash, creating fountains of soil and palls of smoke. Tanks opened fire on enemy machines as the advancing infantry, denied any help across the featureless battlefield, was met by a hail of fire. ‘It was Armageddon,’ recalls one German survivor:

Every second that passed I expected to be my last. Men were falling around me but we just focused on our objective. Our officer was killed in an explosion, my section commander was shot through the neck shortly after . . . Soviet aircraft added to the hell as they appeared through the smoke without warning as we could not hear their engines over the noise of battle. They strafed us time after time, hour after hour . . . Death would have been a merciful release from that hell, but I came through. Those were the worst moments of my war, of my life. I am haunted by memories of it. Absolutely terrifying.

Gradually the two sides closed. Marc Doerr used his machine gun to suppress Soviet positions. ‘I took up a position on the lip of a shell crater and concentrated my fire on a trench approximately 600 yards away where I could see movements . . . As the attack progressed I eventually moved into that trench and found it full of enemy dead. I believe that the Soviets called the MG-42 the Hitler Saw after the noise that it made. It was a fearsome weapon with a tremendous weight of fire.’

The panzers had destroyed numerous T-34s at long range, and then endeavoured to finish off the remaining tanks as the T-34s darted to within a couple of hundred yards of the German formations. The T-34s were pushed to their limits, engines roaring, and as the morning grew warmer, temperatures inside the cabins rose to excruciating levels. The perspiration dripped off the crews’ noses and stung their red-rimmed eyes. Every time the main armaments were fired, the compartment filled with choking, blue-grey cordite fumes. Vladimir Severinov has said:

There was a lethal cocktail of vapours in a T-34 during battle. We once had a loader and then a driver pass out during action, which sent us into a panic as the tank was designed to advance when the throttle pedal was raised, not when it was lowered. We opened the hatch to let the worst of the foul air out and within a few moments the driver was aware enough to apply the brake. We were desperate to get out into the fresh air, but we could hear the rounds splatting against our armour and knew that we would be dead within seconds . . . Being in a tank in July 1943 was like being placed in a hot oven pumped full of toxins and suffocated.

Attacking units disappeared into a cloud of explosions and smoke never to be seen again. The Soviet second line ate up the Wehrmacht’s young men hour after hour – but the divisions’ commanders continued to hammer away. Infiltrations were made and snuffed out, assaults were mounted and crushed. Armour ran into minefields or fell pray to the anti-tank guns and tank-killer teams. Radios were alive with orders, and pleas for information about the progress of reinforcements and supplies. The Soviets hit back with local counterattacks, which sometimes stunned the Germans with their size and ferocity. At 1830 hours, for example, 150 tanks of the 19th Tank Corps struck the 20th and 2nd Panzer Divisions with such force that some regiments were sent reeling. Herbert Forman has testified:

The tanks came out of nowhere. Just as we were beginning to make a little progress. They clattered into us and made a mess of the positions that we had carved at such great expense. Within an hour our own armour had stopped the advance, but the battle continued until darkness and we were left back where we had started from that morning.

In this way, the offensive power of the Tigers was finally broken and the remaining six machines of the 505th Heavy Tank Battalion were withdrawn as the unit underwent a major overhaul and reorganization. Model’s mailed fist, such as it was, had been denied its talisman.

XLVII Panzer Corps had been starved of its ability to manoeuvre and drawn into a cleverly executed slogging match by the enemy. Nowhere was this more apparent than at Ponyri Station, which was to develop into an encounter that became known to the troops as a ‘mini-Stalingrad’. The village of Ponyri nestled in a balka a couple of miles to the west of Ponyri Station, which was a more substantial conurbation that had grown up around the local railway station. With its cluster of warehouses and sturdy buildings, the town, although small, was one of the largest in the area, and it controlled the roads and railways leading south. Its seizure was seen by Model as a means of breaching the Soviets’ second line, rolling it up through Olkhovatka and opening a route to Kursk. Recognizing its importance, the 13th Army was determined to hold on to it at all costs. What resulted, therefore, was a fraught and bloody confrontation to which both sides committed copious resources over several days.

The Germans had already taken the northern part of Ponyri Station on the first day of Zitadelle, and at first light on 6 July, 292nd Infantry Division resumed its assault, supported by elements of the 9th Panzer Division on its right flank. Preceded by a heavy artillery bombardment and Stuka dive bombing, which reduced much of Major-General M.A. Enshin’s 307th Rifle Division defences to rubble, the formations attacked. But the Germans stalled as they tried to pick their way through a protective minefield and over barbed-wire obstacles. These were covered by machine-gun nests and mortars, and the Soviet guns opened up. The Wehrmacht’s attack was immediately stripped of its shape and stuttered forward with heavy losses. Some units managed to break into the town, but became entangled in a network of mutually supportive positions in streets of fortified houses. When the armour followed, they soon became aware of carefully positioned anti-tank guns, which quickly converted the unwary and unlucky into blazing wrecks that blocked the thoroughfares. The infantry endeavoured to clear buildings as they progressed southwards, but where successful they were soon overwhelmed by counterattacks. The Soviets seemed to glory in vicious hand-to-hand fighting.

A simultaneous attack was made to the east of Ponyri Station where the 86th and 78th Infantry Divisions sought to take Hill 253.5 and Prilepy. These positions would not only give the Germans an opportunity to undermine Ponyri’s defences but also offered a means of outflanking the tenacious resistance of Maloarkhangelsk. Nikolai Litvin’s battery was one of those that lay in wait for just such a move. They were situated in a field of uncut rye between two parallel ravines, which was deemed a likely area for a panzer attack. Having camouflaged their guns and established fields of fire, the gun crews prepared themselves for an onslaught. ‘The morning of 6 July dawned cloudy, with a low, overcast sky that hindered the operations of our airforce,’ the inexperienced Litvin says:

At around 6:00 a.m., our position was attacked head-on by a group of approximately 200 submachine gunners and four German tanks, most likely PzKw IVs. The tanks led the way, followed closely by the infantry. The Germans were attempting to find a weak spot in our lines . . . but they didn’t seem to see us. We felt a gnawing fear in the pit of our bellies as the German tanks rumbled toward us, stopping every fifty to seventy metres to scan our lines and fire a round . . . My knees and legs began to tremble wildly, until we received the command to swing into action and prepare to fire. The shaking stopped, and we became possessed by the overriding desire not to miss our targets.

The guns were ordered to fire when the enemy had reached within 300 yards of the line. Litvin continues:

Our Number One gun set a tank ablaze with its first shot, and then managed to knock out a second tank. The combined fire of our Number Three and Number Four guns knocked out a third German tank. The fourth tank managed to escape . . . [My gun] opened up on the advancing infantry with fragmentation shells. The German submachine gunners stubbornly continued to push forward. As they drew closer, we switched to shrapnel shells and resumed fire on them. Not less than half the Germans fell to the ground, and the remaining drew back to their line of departure.

A temporary lull followed during which the Soviet gunners breakfasted and celebrated their success with 100 grams of vodka, but a new push was heralded by a Stuka attack. These bombers were called ‘musicians’ by the Red Army due to their air sirens, which wailed as they dived on their targets. The first bomb exploded some 60 yards from Litvin’s position. Another fell directly above his dug-out:

I saw my own unavoidable death approaching, but I could do nothing to save myself: there was not enough time. It would take me five to six seconds to reach a different shelter, but the bomb had been released close to the ground, and needed only one or two seconds to reach the earth – and me. During those brief seconds as I watched the bomb fall, my entire conscious life flashed through my mind. Everything seemed to happen in slow motion. I badly didn’t want to die at the age of twenty . . . Just before the bomb struck, I rolled over face down in my little trench and covered my face with the palms of my hands . . . I heard the bomb explode. There was a repulsive smell of TNT, and I felt two strong blows to my head. It seemed to me that my head must have been torn off . . . The bomb had exploded very close to my trench, and I was buried in loose dirt.

Pulled unconscious from his entombment, it took three days for Litvin’s hearing to return and another week before he could speak.

Subsequent pushes by the Germans did take ground but there was no breakthrough and Ponyri remained a hornet’s nest in Soviet hands. As Zhukov later wrote: ‘All day the roar of battle on the ground and in the air engulfed the area. Although the enemy kept pouring new tank units into the battle, here again he was unable to achieve a breakthrough.’ On the flanks of the Ninth Army’s front, meanwhile, neither XXIII Corps nor XLVI Panzer Corps could develop their modest first-day territorial gains in any meaningful way and failed to do so for the remainder of Zitadelle. As dusk fell on the 6th, therefore, Rokossovsky had been handed an opportunity to concentrate his defences against the centre of the line. With XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps still flailing through the 13th Army’s main defensive line, the Central Front could feel content that they had managed to take the sting out of Model’s initial blow. They had to remain wary of his reserves, though, and could not afford to relinquish possession of the Olkhovatka heights if they were to wear the Ninth Army down. By taking formations from the quieter areas of his Front – the 70th Army released one division and the 65th Army two tank regiments – Rokossovsky successfully managed to reinforce his defences with a minimum of disruption.

Even as the Central Front took steps to enhance their resistance, Model underwrote plans for his XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps to continue their frontal attacks on the Olkhovatka line. Like so many generals in similar situations down the centuries, when confronted with defences that were expected to break open at any moment, he felt compelled to throw more resources at them to complete the job. If, instead, Model had decided to concentrate his attack elsewhere, he would not only lose whatever momentum had been accrued but might also miss the opportunity to finish off a defence that was on the verge of collapse. Thus, on 7 and 8 July, the Ninth Army continued to pummel away at Olkhovatka’s defences for, in the words of one German observer, ‘here was the key to the door of Kursk,’ which could be seen 400 feet below. Model was convinced he could draw Rokossovsky’s armour and defeat it on unfavourable ground. The fight for this part of the line, therefore, was never going to be anything other than a protracted brawl – the destruction of Soviet reinforcements was all part of the Ninth Army’s plan.

Thus, on the morning of the 7th, XLVII and XLI Panzer Corps pushed forward once more. The attack was to take the form of three mutually supportive but distinct movements: one by the 20th Panzer Division towards the village of Teploe, the second by the 2nd Panzer Division (supported by the briefly rested Tigers of the 505th Heavy Tank Battalion) focusing on Olkhovatka, and the third into and around Ponyri by the 18th Panzer Division (released from the reserve), the 292nd and the 86th Infantry Divisions, supported by the 9th Panzer Division. The 6th Infantry Division was to continue plugging away in the middle of the line and provide a bridge linking the 2nd and 9th Panzer Divisions.

There was little finesse to Model’s plan, which simply seemed to reflect the wider German desire to use brute force to smash holes in the enemy’s positions. The application of the Ninth Army’s force was, however, enhanced on 7 July by the temporary loan of over 500 aircraft from Luftflotte 4. He-111s and Ju-88s appeared over the battle lines at first light to soften the Soviets’ defences, and were followed by Stukas operating just in front of the advancing panzers. As the ground formations once again became locked in combat, the Red Air Force sought to neutralize the Luftwaffe by smothering the front with aircraft. Although their losses were heavy – Stalin’s pilots remained less capable than their rivals – the Soviets did succeed in denying the Luftwaffe freedom of movement in the skies above the battlefield. Indeed, as the Red Air Force’s sorties increased and the Germans’ declined for want of petrol, oil and lubricants and serviceable air – frames, it was the Soviets who achieved general and local air superiority over the Central Front, and this situation persisted throughout the rest of the operation. General der Flieger Friedrich Kless, Chief of Staff of Luftflotte 6, said:

By 7–8 July the Soviets were able to keep strong formations in the air around the clock . . . Unremitting air actions of extended duration necessarily caused the technical serviceability of our formations to decrease, therefore making it unavoidable that the quantitative Soviet superiority should temporarily be in a position to act directly against German troops during temporal and spatial gaps in the Luftwaffe fighter coverage . . . Russian air attacks began to hit the important supply roads of our spearhead divisions to an increasing extent, with raids striking points as far as [15 miles] behind German lines.

Often lacking the support of air artillery, upon which they had come to depend, the panzer formations felt vulnerable. Without the ground-based firepower, or boots on the ground to make up for this deficit, casualties mounted. Detailing the 20th Panzer Division’s attack on Samodurovka, Paul Carell has written:

Lieutenant Hänsch rallied his small handful of men: ‘Let’s go, men, one more trench!’ The machine-gun rattled. A flamethrower hissed ahead of them. Two assault guns were giving them fire cover. They succeeded. But the lieutenant lay dead, twenty paces in front of his objective, and around him, dead and wounded, lay half his company.

Within an hour of closing with the enemy, all the officers of the 5th Company, 112th Panzer Grenadier Regiment, had become casualties. Other units suffered similar fates and with their attacks withering, some were forced to withdraw. Others, however, forged on and, in a series of local battles, managed to avoid the minefields, prise the Soviets from their trenches, overwhelm the anti-tank guns and perforate the defences. By noon, a two-mile gap had been created between the villages of Samodurovka and Kashara through which poured the Tigers followed by the 2nd and 20th Panzer Divisions. It was a critical moment in the battle for with the 6th Guards Rifle Division’s left flank crumbling, XLVII Panzer Corps had gained a position from which they could make a direct assault on the Olkhovatka heights.

The situation had, however, been anticipated, and the Soviets were well placed to deal with it with the minimum of fuss. The 17th Guards Rifle Corps, supported by the 13th Army, had already acted to ensure that the ridge was well protected. Having surmounted one line of obstacles, the panzer divisions would have to do the same again if they wanted to gain the ridge. From their observation posts, the Soviet commanders peered through their field glasses at a scene of unremitting carnage as the tiring German thrust was subjected to the close attention of the Red Air Force. Valentin Lebedev, an infantry company commander, recalls:

We could see the tanks assembling for an attack when they were attacked by Yaks and Il-2s. They were sitting targets and despite the best efforts of their anti-aircraft teams, wave after wave of aircraft flew in and did a great deal of damage. After about half an hour, it seemed as if the entire German army had caught fire. Unfortunately, that was not the case.

The Yak 9Ts, sporting 37mm cannon, and the Il-2s, carrying the new PTAB hollow-charge bomblets (which were being used for the first time), were well armed for their mission. The cannon were capable of ripping through 30mm of armour while the bomblets could penetrate 60mm. The turrets of the Panzer IIIs and IVs were just 10mm thick. Constantly moving to provide more difficult targets for the Soviet pilots to hit, the panzers were in poor order when the aircraft suddenly disappeared and dozens of T-34s were already at close range.

Feldwebel Günther Krause’s Tiger took a round in its relatively lightly armoured flank, which set fire to the engine and badly wounded the loader. Krause wasted no time in ordering the crew to bail out and the loader’s limp body was unceremoniously hauled out of the turret hatch as the tank continued to attract incoming small-arms fire. Throwing themselves into a ditch, the five men were then faced with the approach of enemy infantry, who had seen what had happened and were intent on denying the Wehrmacht the services of an experienced crew. Taking up their MP-40 sub-machine-guns and firing at the infantrymen in short bursts, Krause and his driver provided covering fire while the still unconscious loader was carried to the relative safety of a nearby copse. Once their three colleagues had successfully reached the trees, the two men joined them. As they did so, three Tigers came into view to rescue them – two occupied the enemy; the third rolled up by the patch of trees and took them on board.

The German attack on the Olkhovatka heights had been stopped before it even started. By dislocating the two panzer divisions with the airforce and following up with a well-timed counterattack, the Soviets had managed to maintain the integrity of the high ground for another day. Model had little more success at Ponyri. The 6th Infantry Division managed to take the village of Bitiug and the 9th Panzer Division advanced to Berezovyi Log, but overall the attack by the three divisions of XLI Panzer Corps on Ponyri failed to make much of an impression. Despite the additional firepower offered by the 18th Panzer Division, the 307th Rifle Division continued to hold out. Some parts of the town changed hands several times throughout the day but, critically, the Germans were deprived of the opportunity to make a concerted assault with a concentration of armoured vehicles by successful Soviet efforts to splinter their attempted drives. Assisted by battle debris, which included numerous burnt-out vehicles, the Soviets fought back. Tanks were dispatched by mines, guns and Molotov cocktails; the infantry were immobilized by field artillery, mortars and interlocking machine-gun fire. Any groups of Germans who did manage a degree of penetration into Soviet-held territory were ruthlessly hunted down by sections armed with sub-machine-guns, bombs and combat knives. There was little time for the combatants fighting in this arena to rest as the struggle played out within the narrow confines of Ponyri and its immediate surroundings. Assault after assault was launched into the town, and assault after assault was fended off as Rokossovsky flooded the area with guns. The unrelenting nature of the confrontation at Ponyri would never be forgotten by its participants on either side. For some the pressure was too much. Interviewing men who had fought in the battle weeks later, Vasily Grossman noted: ‘Stories about 45mm cannons firing at [Tiger] tanks. Shells hit them, but bounced off like peas. There have been cases where artillerists went insane after seeing this.’

Disappointing though 7 July was for Model, since the Soviet defences had not collapsed and the Ninth Army was still stuck in the second line, the Soviets had been rocked. The Central Front was coping with the pressure of the offensive, but Rokossovsky’s need for resources meant that he had to take units from less active parts of the front to reinforce his beleaguered 13th Army. The depth of the need can be gauged from the decision to draw on those units – such as IX Armoured Corps – that had been specifically positioned to defend the city of Kursk. It was a gamble, but at least these important deployments took place in the knowledge that Central Front intelligence ruled out a new German threat emerging elsewhere in the northern salient. Intelligence also told Rokossovsky that Model’s reserves were running out. The Germans were offering a considerable challenge, but the Soviet defences were robust. The Ninth Army was being worn down and denied territorial advantage. As long as the Central Front could resource its operations for longer than the Ninth Army could sustain theirs, Soviet chances of success were good. Model’s continued offensive action in the centre of the line over the next three days consequently played into Rokossovsky’s hands.