British support for the resistance in Yugoslavia had thus far troubled the Wehrmacht little. Although up to thirty Axis divisions had been engaged in internal security operations in the Yugoslav mountains, including Italian, Bulgarian, Hungarian and Croat (Ustashi) formations, only twelve were German, most of a military value too low to permit their employment on the major battlefronts. Even after the British had definitively transferred their sponsorship of Yugoslav resistance in December 1943 from the royalist Chetniks to Tito’s communist guerrillas, who then numbered over 100,000, the Germans were able to keep the resistance forces constantly on the move, forcing them to migrate from Bosnia to Montenegro and then back again during the campaigning season of 1943 and in the process inflicting 20,000 casualties on their troops, as well as untold suffering on the rural population. The capitulation of Italy in September 1943 had eased Tito’s situation. It brought him large quantities of surrendered arms and equipment and even allowed him to take control of much of the area relinquished by the Italians, including the Dalmatian coast and the Adriatic islands. However, as long as the Germans continued to isolate the Partisans from direct contact with external regular forces, the rules of guerrilla warfare applied: Tito had a strong nuisance value but an insignificant strategic effect on Germany’s lines of communication with Greece and the areas from which it drew essential supplies of minerals.

In the autumn of 1944, however, Germany’s position in the Balkans began to weaken, so threatening to elevate Tito from the role of nuisance to menace. Hitler’s Balkan satellites, Bulgaria, Romania and Hungary, had been brought into the war on his side by a combination of threat and inducement. Hitler could no longer offer inducement, while the principal threat to these states’ welfare and sovereignty was now prescribed by the Red Army, which between March and August had reconquered the western Ukraine and advanced to the foothills of the Carpathians, southern Europe’s natural frontier with the Russian lands. Much earlier in the year the satellites had begun to think better of their alliance with Hitler. Antonescu, the ruler of Romania, had been in touch with the Western Allies since March; his Foreign Minister had even attempted to draw Mussolini into a scheme for making a separate peace as early as May 1943. Bulgaria – whose staunchly pro-German King Boris died by poisoning on 24 August 1943 – had made approaches to London and Washington in January 1944 and then placed its hopes in coming to an understanding with Stalin. Hungary, which had benefited so greatly at Romania’s expense by the Vienna Award of August 1940, was meanwhile playing its own game: Kallay, the Prime Minister, had made contact with the West in September 1943 with the aim of arranging through them a surrender to the Russians, while the chief of staff suggested to Keitel, head of OKW, that the Carpathians be defended by Hungarian troops only – a device intended to keep not so much German as Romanian troops off the national territory.

Even while the German troops were in full retreat in Italy and the Russians were advancing irresistibly to the Carpathians, Hitler could deal with Hungary. He had easily put down a revolt in the puppet state of Slovakia, raised by dissident soldiers in July when they imminently but over-optimistically expected the arrival of the Red Army on their doorstep. In March he had quelled the Hungarians’ initial display of independence by requiring Admiral Horthy, the Hungarian dictator, to dismiss Kallay and grant Germany full control of the Hungarian economy and communications system and rights of free movement into and through the country by the Wehrmacht. Horthy’s dismissal of his pro-German cabinet on 29 August alerted Hitler to the revived danger of Hungary’s defection. When on 15 October, therefore, Horthy revealed to the German embassy in Budapest that he had signed an armistice with Russia, German sympathisers in Horthy’s Arrow Cross party and in the army were ready to take control of the government. Horthy was isolated in his residence, where he was persuaded to deliver himself into German hands after Skorzeny, the rescuer of Mussolini, had kidnapped his son as a hostage.

The occupation of Hungary, though smoothly achieved, could not at that stage halt the unravelling of the Balkan skein. Hungary had ultimately been driven into opening negotiations with the Russians because it feared, quite correctly, that Romania might otherwise make its own deal with Stalin and secure the return of Transylvania, which it had been forced to cede to Horthy under the Vienna Award. However, it was Hungary that had been forestalled; as soon as the Red Army crossed the Dniester from the Ukraine on 20 August, King Michael had had Antonescu arrested, thus provoking Hitler to order the bombing of Bucharest on 23 August and so allowing Romania to declare war on Germany next day. This change of sides forced the German Sixth Army (reconstituted since Stalingrad) into precipitate retreat towards the passes of the Carpathians. Few of its 200,000 men escaped. Bulgaria, into which they might have fled southward, was now closed to them because on 5 September the government had opened negotiations with the Russians (with whom it had never been at war) and promptly turned its army against Hitler. In Romania, reported Friesner, the commander of the Sixth Army, ‘there’s no longer any general staff and nothing but chaos, everyone, from general to clerk, has got a rifle and is fighting to the last bullet.’

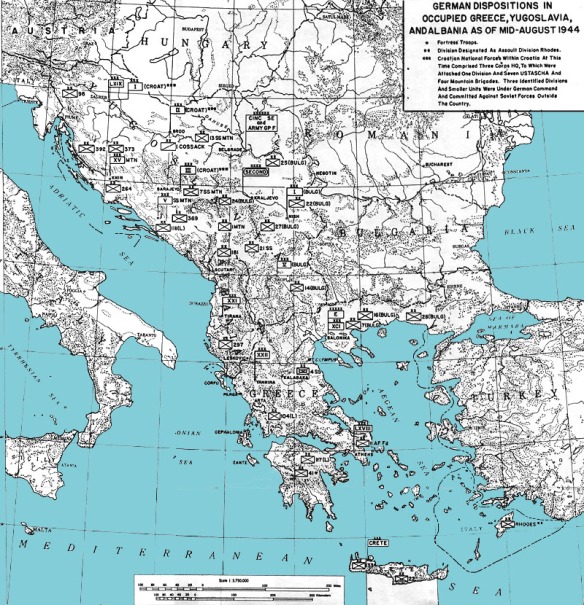

The defection of Romania immediately entailed the loss of access to the Ploesti oilfields, fear of which had so deeply influenced Hitler’s strategic decision-making throughout the war. It was that fear which, in large measure, had driven him to take control of the Balkans in the first place, to contemplate the attack on Russia, and to hold the Crimea long after it was militarily sound to do so. Now that the synthetic oil plants which had subsequently come on stream within Germany had been brought under disabling attack by the US Eighth Air Force, the loss of Ploesti was doubly disastrous. However, Hitler could not hope to recover them by counter-attack, for not only did the Russian Ukrainian Fronts which entered Romania on its defection enormously outnumber his own local forces; the simultaneous defection of Bulgaria put the German forces in Greece at risk also and on 18 October they evacuated the country and began a difficult withdrawal through the Macedonian mountains into southern Yugoslavia. Tolbukhin, commanding the Third Ukrainian Front, entered Belgrade, the Yugoslav capital, on 4 October, having made his way there through Romania and Bulgaria. The 350,000 Germans under the command of General Löhr’s Army Group E thus had to make their escape from Greece past the flank of a menacing Soviet concentration, through mountain valleys infested with Tito’s Partisans and overflown by the Allied air forces operating across the Adriatic from their bases in Italy.

The security of the other German forces – Army Group F – in what remained to Hitler of his Balkan occupation area now closely depended upon Kesselring’s ability to defend northern Italy. Should it fall, Allied Armies Italy would be free both to strike eastward through the ‘gaps’, notably the Ljubljana gap which led into northern Yugoslavia and so towards Hungary, and also to launch major amphibious operations from the northern Italian ports across the Adriatic, as the commanders of Land Forces Adriatic, supported by the Balkan Air Force (established at Bari in June 1944), had already begun to do on a small scale. At a meeting with Stalin in Moscow in October 1944, Churchill concluded a remarkable, if largely unenforceable, agreement advocating ‘proportions of influence’ between Russia and Britain in the Balkans. Unlike the Americans, Churchill continued to be fascinated by the opportunities that a Balkan venture offered. In the event it was not Allied scheming but German force allocation that decided the issue. By the time the Fifth and Eighth Armies reached the Gothic Line, their strength stood at only twenty-one divisions, while that of the German Tenth and Fourteenth, thanks to the transfer of five fresh formations and the manpower for three others, had increased to twenty-six. Although the Gothic Line was eighty miles longer than the Winter Position, it was backed by an excellent lateral road, the old Roman Emilian Way from Bologna to Rimini, which allowed reinforcements to be sped from one point of danger to the other, and on the Adriatic coast was backed by no fewer than thirteen rivers flowing to the sea, each of which formed a major military obstacle.

This terrain and the onset of Italy’s autumn rains now ensured that Kesselring’s hold on northern Italy, if not the whole of the Gothic Line itself, could not be broken. Alexander, correctly assessing that the route towards the great open plain of the river Po was more easily negotiable on the right than on the left, secretly had transferred the bulk of the Eighth Army to the Adriatic coast during August. On 25 August it attacked, broke the Gothic Line and advanced to within ten miles of Rimini before being halted on the Couca river. While it paused to regroup, Vietinghoff, commanding the Fourteenth Army, rushed reinforcements along the Emilian Way to check its advance. The British renewed the offensive on 12 September but were fiercely opposed; the 1st Armoured Division lost so many of its tanks that it had to be withdrawn from offensive operations. In order to divert enemy strength from the British front, Alexander ordered Clark to open his own offensive on the opposite coast on 17 September, through the much less promising territory north of Pisa. So narrow is the coastal plain there, dominated by heights reminiscent of Cassino, that it made very slow progress. During October and into November, as rains turned the whole battlefield into a slough and raised rivers in unbridgeable spate, the campaign dragged on, while ground was won in miles and lives lost in thousands. The Eighth Army lost 14,000 killed and wounded in the autumn fighting on the Adriatic coast, the Canadians bearing the heaviest share, for they were in the forefront. The Canadian II Corps took Ravenna on 5 December and pushed onwards to reach the Senio river by 4 January 1945. The Fifth Army, attacking through the mountains of the centre, reached to within nine miles of Bologna by 23 October; but it had also lost very heavily – over 15,000 killed and wounded – and was confronted by terrain even more difficult than that on the Eighth Army’s front. So weakened was it that a surprise German offensive in December won back some of the ground it had captured in September north of Pisa.

Losses, terrain and winter weather determined that at Christmas 1944 the campaign in Italy came to a halt. It had been a gruelling passage of fighting, almost from the first optimistic weeks of landing and the easy advances south of Rome sixteen months earlier. The spectacular beauty of Italy, natural and man-made, its scenery of crags and mountain-top villages, ruined castles and fast-flowing rivers, threatened danger at every turn to soldiers bent on conquest. The painters whose landscapes had delighted European collectors had left warnings to any general with a sharp eye of how difficult an advance across the topography they depicted must be to an army, particularly a modern army encumbered with artillery and wheeled and tracked vehicles. Salvator Rosa’s savage mountain landscapes and battle scenes spoke for themselves. Claude Lorrain’s deceptively serene vistas of gentle plains and blue distances were equally imbued with menace; painted from points of dominance that an artillery officer would automatically choose as his observation post, they demonstrate at a glance how easily and regularly ground can be commanded by the defender in Italy and what a wealth of obstacles – streams, lakes, free-standing hills, mountain spurs and abrupt defiles – the countryside offers. The engineers were the consistent heroes of the campaign in Italy in 1943-4; it was they who rebuilt under fire the blown bridges the Allied armies encountered at five- or ten-mile intervals in the course of their advance up the peninsula, who dismantled the demolition charges and booby traps the Germans strewed in their wake, who bulldozed a way through the ruined towns which straddled the north-south roads, who cleared the harbours choked by the destruction of battle. The infantry too proved heroic: no campaign in the west cost the infantry more than Italy, in lives lost and wounds suffered in bitter small-scale fighting around strongpoints at the Winter Position, the Anzio perimeter and the Gothic Line. Such losses were shared equally by the Allies and the Germans, as were the natural hardships of the campaign, above all the bleakness of the Italian winter. As S. Bidwell and D. Graham put it in their history of the campaign: ‘A post on some craggy knife-edge would be held by four or five men . . . if one of them were wounded he would have to remain with the squad or find his own way down the mountain to an aid post . . . if he stayed he was a burden to his friends and would freeze to death or die from loss of blood. If he tried to find his way down the mountain it was all too easy . . . to rest in a sheltered spot . . . or lose his way . . . and die of exposure.’ Many of the Germans of the 1st Parachute Division who held Cassino so tenaciously must have come to such an end; many, too, of the Americans, British, Indians, South Africans, Canadians, New Zealanders, Poles, Frenchmen and (later) Brazilians who opposed them there and at the Gothic Line.

Losses and hardships were made the more difficult to bear, particularly by the Allies, because of the campaign’s marginality. The Germans knew that they were holding the enemy at arm’s length from the southern borders of the Reich. The Allies, after D-Day, were denied any sense of fighting a decisive campaign. At best they were sustaining the threat to the ‘soft underbelly’ (Churchill’s phrase) of Hitler’s Europe, at worst merely tying down enemy divisions. Mark Clark, commander of the Fifth Army and, under Alexander, of Allied Armies Italy, sustained his sense of personal mission throughout. Convinced of his greatness as a general, he drove his subordinates hard, and his frustration at the deliberation of British methods poisoned relations between the staffs of the Fifth and Eighth Armies – a deplorable but undeniable ingredient of the campaign. More junior commanders and the common soldiers were sustained, once the spirit of resistance to German occupation had taken root among the Italians, by the emotions of fighting a war of liberation. No great vision of victory drew them onward, however, as it did their comrades who landed in France. Their war was not a crusade but, in almost every respect, an old-fashioned one of strategic diversion on the maritime flank of a continental enemy, the ‘Peninsular War’ of 1939-45. That they were continuing to fight it so hard when winter brought the campaigning season to an end at Christmas 1944 was a tribute to their sense of purpose and stoutness of heart.