The Dutch were particularly fond of privateers. Piet Heyn amazingly captured the whole of the Spanish treasure fleet – complete with gold and silver booty from its American colonies – during the Battle in the Bay of Matanzas in September 1628. Heyn became a folk hero and part of a Golden Age of Dutch enterprise, which saw an expanding commercial empire buoyed by the maritime prowess of its sailors. Simultaneously, however, the Dutch were quick to punish piracy. Without sanction, and an agreed fee to the Crown, pirates would be executed.

When the Catalans continued their protests that by April 1640 had turned into armed resistance against the troops there to defend them. The troops were merely the focus of much deeper popular discontent at years of corrupt administration. The famed liberties were mainly restricted to the aristocracy that dominated the kingdom’s assembly (the Corts) and manipulated their privileges for their own ends. The right to bear arms, for example, was used to cloak widespread banditry as lords sponsored gangs to pursue feuds with their neighbours. ‘A mafia-type regime prevailed in parts of Catalonia, sustained by violence and extortion.’ Under these conditions, the protesters did not see their actions as disobedience but as an attempt to draw Philip IV’s attention to their plight.

Peasants armed with scythes entered Barcelona on 22 May 1640 and opened the jail. Alarmed, the viceroy cancelled the Corpus Christi procession scheduled for 7 June. Around 2,000 ‘reapers’ (segadors) protested anyway, triggering four days of rioting. The viceroy and a leading judge were murdered, while other officials fled or went into hiding. Madrid and the provincial authorities blamed each other for the disorder that now spread across the kingdom.

The insurrection threatened the aristocracy’s privileges, but these would also be curtailed if Philip IV were to crush the revolt. The aristocrats sought another way out, opening negotiations with France, and agreeing on 29 September to open the ports to French ships and maintain the 3,000 auxiliaries despatched by Richelieu to assist them. Olivares believed he was facing a second Dutch Revolt and summoned an emergency levy of men across the loyal provinces. The marquis de los Vélez was sworn in as the new viceroy at the head of 20,000 men in southern Catalonia on 23 November. He retook Tortosa and the important port of Tarragona, which was also the seat of the archbishop of Catalonia.

Richelieu initially regarded the revolt as a welcome diversion from the crisis in Italy as the siege of Turin reached its climax. He was prepared to recognize Catalonia as an aristocratic republic that could serve as a useful buffer between France and Spain. The deteriorating situation following Los Vélez’s advance forced him to despatch another 13,000 men to reinforce the rebels. The royalists reached Barcelona at the end of December. Their appearance compromised the provincial government that was accused of failing to defend the kingdom. Following the murders of five more judges, the survivors placed themselves under French protection on 23 January 1641, accepting Louis XIII as ‘count of Barcelona’ and effectively ceding Roussillon. Three days later, the combined Franco-Catalan army defeated Los Vélez on Montjuic hill outside the city.

The rebels had passed the point of no return, but ‘acquired the burden of power without any of the fruits’. Half the French effort was directed at conquering Roussillon where Spain still held Perpignan and other key fortresses. Only half the army was sent into Catalonia where fighting concentrated around Lérida (Lleida) to the west of Barcelona, the town that commanded the main road from Castile into the kingdom.

The Catalans were joined from December 1640 by the Portuguese, opening a new Iberian front to the west. The Portuguese had contributed a comparatively modest 1 million cruzados to Spain’s war effort after 1619. Madrid’s demand for 3 million in 1634 struck them as completely unreasonable. Tax revolts erupted in three of the kingdom’s provinces during 1637 just as key parts of the Portuguese empire were lost to the Dutch as well. These problems stirred the latent resentment at the loss of independence. Olivares’ suppression of the Council of Portugal in 1638 did nothing to help this. Anti-Hispanicism mixed with anti-Semitism as Lisbon Jews and Conversos were integrated into Spain’s financial system after 1627 to take up the slack left by the inability of Genoese bankers to manage the burgeoning debt. Anti-Semitism encouraged popular and clerical support for the break with Spain. The yearning for independence was expressed as the Sebastian myth – that the country’s last native king who ‘disappeared’ at the battle of Alcazarquivir (al-Qasr el-Kabir) in Morocco in 1578 would eventually return. Unlike in Bohemia or Catalonia, the presence of the native Braganza dynasty offered a powerful focus for the coming revolt.

Its trigger was the demand in June 1640 for 6,000 Portuguese troops to assist in crushing the Catalonians. Portuguese malcontents stormed the Lisbon palace of the vicereine, Margarita of Savoy, and threw her adviser, Miguel de Vasconcellos, out of the window in the Bohemian fashion on 1 December. The vicereine was bundled over the frontier and Spanish resistance collapsed. Apart from Ceuta in North Africa, the Portuguese colonial empire recognized the new regime in 1641.

The ensuing conflict is known in Portuguese history as the War of Restoration (1640–68). Left largely alone, the Portuguese were able to improvise an army almost from scratch and launch an offensive into Spain in June 1641. Pope Urban received their ambassador, implying recognition, in 1642, while the English agreed an alliance that was later (1660) renewed with the marriage of Catherine of Braganza to Charles II, the match that saw Bombay and, briefly, Tangiers pass to English rule. However, fighting remained limited until the 1650s because Olivares concentrated on combating the Catalan revolt, since this provided an open door to French invasion. The Portuguese opposed Spanish rule, but they still shared a common enemy in the Dutch who continued their conquests in the Portuguese colonies.

The general sense of failure was magnified by bad news from the Indies, the region that had come to symbolize Iberian wealth and power. The Portuguese held on to Goa and Mozambique, but were expelled from Japan by local opposition in 1639. A protracted struggle with the king of Kandy for control of Sri Lanka opened the island to the Dutch who joined the local campaign to eject the Portuguese after 1636. The conflict drained the resources of the Estado da India, undermining resistance elsewhere to the Dutch who had captured most of the Indonesian spice islands by 1641.

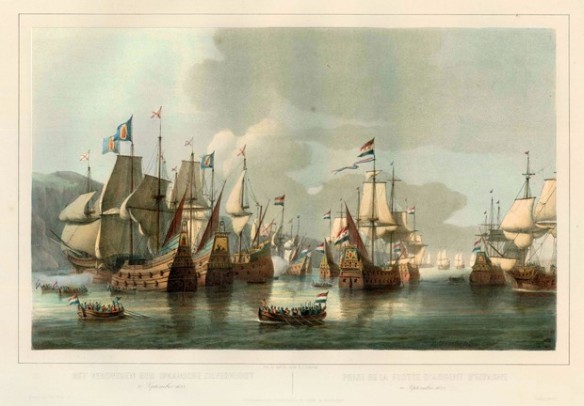

The situation in the West Indies was equally bleak. Using the Matanzas loot, the Dutch West India Company fitted out 67 ships, with 1,170 guns and carrying 7,280 men under Admiral Hendrik Loncq. This was twice the manpower and three times the number of ships deployed to defend Portuguese Brazil. Loncq captured Olinde and Recife, the principal ports of Pernambuco in February 1630. Olivares despatched Spain’s senior admiral, Antonio Oquendo, with 56 ships and 2,000 soldiers to retake the towns before the Dutch could penetrate the sugar-producing hinterland. Oquendo eventually defeated the Dutch off Abrolhos in September 1631. Battered and with no harbour in which to refit his ships, Oquendo was obliged to return to Lisbon. The Dutch extended their positions, occupying the Guianan coast between the Amazon and modern Venezuela. The subsequent capture of Curaçao island in 1634 secured the local salt trade, vital to the Dutch herring industry.

A second relief effort in 1635 similarly failed to dislodge the Dutch, in stark contrast to the successful expedition a decade before. The Brazilian planters realized they would have to collaborate with the occupiers to safeguard their incomes. Portuguese control in Brazil shrank dramatically after the arrival of the energetic Prince of Nassau-Siegen as Dutch governor in January 1637. He won local support by allowing Catholic convents and monasteries to remain open, conducted the first scientific survey of the area and extended Dutch control to 1,800km of the coast by 1641 with a force of only 3,600 Europeans and 1,000 Indians. Two further Portuguese expeditions were repulsed in 1638 and 1640. Meanwhile, the Dutch capture of Elmina on Africa’s Gold Coast in 1637 gave them Portugal’s main slaving base. The Dutch exploited Portugal’s difficulties with Queen Njinga to take Luanda and other positions in Angola by 1641. Axim, the last Portuguese fort on the Gold Coast, fell the following year. Dutch slavers had shipped 30,000 Africans to Brazil by 1654. Dutch sugar exports to Europe between 1637 and 1644 already totalled 7.7 million florins, while other colonial produce worth 20.3 million was shipped over the same period.

Spain’s transatlantic trade collapsed in 1638–41. No treasure reached Seville in 1640. The Tierra Firme fleet brought only half a million ducats the following year, while the New Spain fleet sailed too late in the season and was hit by a hurricane as it left the Bahama Channel. Ten ships went down with 1.8 million ducats. The gross tonnage crossing the Atlantic by the later 1640s was nearly 60 per cent below that during the Twelve Years Truce. Silver continued to get through, but little more than 40 per cent of that produced in the New World was officially declared in Seville, while crown receipts were less than half those of the 1630s. Part of the decline was due to the increased cost of colonial defence, but much disappeared through fraud and the fact that the war forced the colonies to become more self-sufficient and develop their own trade outside the official system.