In the summer of 1608 an Englishman arrived at the small palazzo near the Grand Canal that served as the official residence of Sir Henry Wotton, James I’s ambassador at Venice. The sailor’s name was Henry Pepwell, and he was just come from Tunis, where he had been gathering intelligence about an English pirate called Ward.

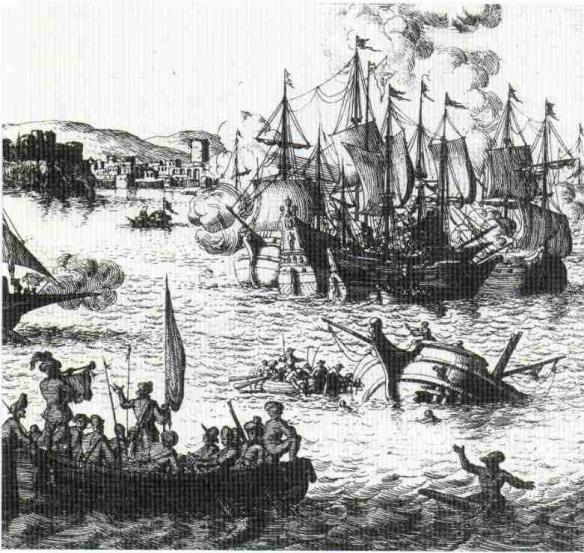

“Captain Ward” had been wreaking havoc in the Mediterranean for the past two or three years, and the English and Venetian authorities were desperate for any intelligence that might help them put an end to his activities. Pepwell told the ambassador how Ward’s criminal career began when he stole a small ship on the south coast of England; how he had settled in Tunis and formed a lucrative partnership with the Muslim ruler there; how his pirate fleet was now heading for the Straits of Gibraltar and the North Atlantic, and how he had vowed “to spare no one whom he can defeat.”

In the course of his story, which Wotton took straight round to the Ducal Palace and presented to the doge, the informant gave a description of the man who was fast becoming the most notorious pirate in Europe:

John Ward, commonly called Captain Ward, is about 55 years of age. Very short, with little hair, and that quite white; bald in front; swarthy face and beard. Speaks little, and almost always swearing. Drunk from morn till night. Most prodigal and plucky. Sleeps a great deal. . . .

This unprepossessing word picture is the only information we possess about the physical appearance of the greatest pirate of his age. Half man, half legend, John Ward was the arch-pirate, the corsair king of popular folk culture. London street balladeers sang of how the “most famous pirate of the world” terrorized the merchants of France and Spain, Portugal and Venice, and routed the mighty Knights of Malta with his bravery and cunning. Parents scared their children with tales of the demon who “feareth neither God nor the Devil, / [Whose] deeds are bad, his thoughts are evil,” and scared each other with reports that those who fell into his clutches would be tied back-to-back and thrown overboard, or cut in pieces, or shot to death without mercy. Clergymen in their pulpits thundered that Ward and his renegades would end their days in drunkenness, lechery, and sodomy within the sybaritic confines of their Tunisian palace, while congregations wondered idly if drunkenness, lechery, and sodomy were really such a bad way to go.

The “most famous pirate of the world” was one among thousands of disenchanted, disempowered sailors who turned to piracy in the early 1600s. Most had once been privateers, sailing with legitimate commissions that authorized them to capture for profit merchant shipping belonging to an enemy; all of the pirate leaders who were hanged at Wapping in December 1609 had begun their careers during the English wars with Spain, which started in 1585 and dragged on intermittently for the next two decades. They attacked Spanish merchant shipping but remained on the right side of the English law by obtaining letters of marque and reprisal, government licenses which authorized them to attack ships belonging to Spain and her allies.

This was an international tradition of state-sanctioned piracy which stretched back for centuries. When a group of London merchants had a huge cargo of wool and other merchandise confiscated in Genoa in 1413, the English king, Henry IV, issued letters of marque and reprisal allowing the merchants to detain Genoese men, ships, and goods until full restitution had been made. One hundred and thirty years later, when Henry VIII was at war with France and Scotland, he declared that any English citizen “shall enjoy to his and their own proper use, profit, and commodity, all and singular such ships, vessels, munition, merchandise, wares, victuals, and goods of what nature and quality soever it be, which they shall take of any of his Majesty’s said enemies.” Elizabeth I’s government regularly issued letters of marque (and took a tenth of the prize money along with customs duties on prize goods); and most of the sixteenth century’s greatest English sailors carried such letters or financed expeditions that depended on them. The explorer Sir John Hawkins promoted privateering ventures, as did the entrepreneurial Sir Walter Raleigh; Christopher Newport, one of the founders of the Jamestown settlement in Virginia, brought prize cargoes of hides, sugar, and spices taken from Spanish shipping in the West Indies to the port of London in the 1590s; Martin Frobisher and Sir Humphrey Gilbert were both involved in privateering. Sir Francis Drake was careful to take letters of marque with him on his voyage round the world, authorizing him to harass Spanish and Portuguese shipping. (At least, he said he did: he refused to show them to anyone who might have been able to understand them.)

The legal rights and wrongs with regard to such letters of commission could be hard to disentangle. If an English privateer attacked and captured a Spanish merchantman while England was at war with Spain, the status of the prize was fairly straightforward: it belonged to the privateer and his backers. But what if an Englishman operating with Dutch letters of marque took a Venetian ship, claiming that it was carrying goods to one of Spain’s allies? Where did the Venetian merchant go for redress? The English Admiralty might make sympathetic noises, but that merchant would be fortunate indeed if he ever saw his goods again. Elizabeth’s government was notoriously flexible when it came to interpreting the legitimacy of letters of marque. Senior courtiers, and even the queen herself, invested in privateering ventures, and if this led to conflicts of interest, they frequently resolved those conflicts in their own favor. And in 1585 the government, concerned that prizes taken by English vessels were being sold unsupervised in foreign ports, ordered that all prizes must pass through the Admiralty Court in London for sentence of forfeiture. Since the Lord Admiral came in for a percentage of their value, there was good reason for Elizabeth’s senior officials to turn a blind eye to the activities of mariners who blurred the distinction between privateer and pirate.

Privateering was big business. In the aftermath of the defeat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, one hundred prizes were brought into English ports every year: together with their cargoes of wines and calicos and sugar and spices, their value amounted to some £200,000, the equivalent of fifteen percent of all annual imports. Years later, the Venetian ambassador reckoned that “nothing is thought to have enriched the English or done so much to allow many individuals to amass the wealth they are known to possess as the wars with the Spaniards in the time of Queen Elizabeth. All were permitted to go privateering, and they plundered not only Spaniards but all others indifferently, so that they enriched themselves by a constant stream of booty.”

This particular route to prosperity at sea came to an abrupt end when James I came to the throne in 1603. The pragmatic and peace-loving James was determined to make peace with Spain, and he immediately issued a proclamation declaring that recent prizes collected by English ships had to be returned, and that anyone who persisted in attacking Spanish shipping after the date of the proclamation would be treated as a pirate. In September 1603 a second royal proclamation, this time “to repress all piracies and depredations upon the sea,” set out in no uncertain terms the consequences of ignoring the first:

No man of war [shall] be furnished or set out to sea by any of his Majesty’s subjects, under pain of death and confiscation of lands and goods, not only to the captains and mariners, but also to the owners and victuallers, if the company of the said ship shall commit any piracy, depredation or murder at the sea, upon any of his Majesty’s friends.

Over the summer of 1604 the Somerset House peace conference brought the Anglo-Spanish wars to an end; a treaty to that effect was signed on August 16. In response, some English privateers offered their services to the Dutch Republic, which remained at war with Spain until the signing of the Twelve Years’ Truce five years later—but in 1605, James I did his best to stop the looting of foreign ships by English privateers by calling home all English seamen serving with foreign powers and prohibiting vessels that carried letters of marque from victualing, or resupplying themselves, at British ports. Anyone who failed to comply would be regarded as a pirate, and, warned the king, “We will cause our laws to be fully executed according to their true meaning, both against the pirates, and all receivers and abettors of them.”

At the same time as he was outlawing English privateering, James I was also running down his navy, and thus making it much harder for Englishmen who wanted a legitimate naval career to find work. By 1607 the English navy, which had been the envy of Europe, numbered only thirty-seven ships, “many of them old and rotten, and barely fit for service,” according to the Venetian ambassador.8 The privateer Richard Bishop articulated the resentment felt by many seafarers when he complained that the king “hath lessened by this general peace the flourishing employment that we seafaring men do bleed for at sea.” Having enjoyed prosperity at sea, many sailors found it hard to give up the life: “We have spent our hours in a high flood, and it will be unsavory for us now, to pick up our crumbs in a low ebb.”

Those sentiments were echoed by John Ward. Born in the Kentish port of Faversham around 1553, he first went to sea as a fisherman; then he became a privateer; and, after James I banned privateering, he joined the king’s navy, serving aboard the Lion’s Whelp, a fast, lightly armed vessel that patrolled the English Channel on the lookout for pirates operating out of Dunkirk. By all accounts he was a morose character, given to heavy drinking and self-pity. He spent his time ashore in taverns, where he would “sit melancholy, speak doggedly, curse the time, repine at other men’s good fortunes, and complain of the hard crosses [that] attended his own.”

Andrew Barker, an English sailor who was held for ransom in Tunis after his vessel was captured by Ward’s pirates in 1608, wrote a vivid account of Ward’s career. A True and Certain Report of the Beginning, Proceedings, Overthrows and Now Present Estate of Captain Ward, which appeared in October 1609, is imaginative, self-conscious, and packed with rhetorical flourishes, but it nevertheless stays very close to the spirit, if not the letter, of the truth.

For instance, one night when the Lion’s Whelp was in Portsmouth harbor and the crew had been given shore leave, Barker has his antihero launch into a tirade about how life has changed for the worse for English seamen since James I came to the throne:

Here’s a scurvy world, and as scurvily we live in it. . . . Where are the days that have been, and the season that we have seen, when we might sing, swear, drink, drab [i.e., whore], and kill men as freely, as your cake-makers do flies? When we might do what we list, and the law would bear us out in it? Nay, when we might lawfully do that, we shall be hanged for and we do [it] now? When the whole sea was our empire, where we rob at will?

The words that Barker put into Ward’s mouth—for he must have, as he couldn’t have heard him speak them—could have come from any one of a thousand disgruntled Jacobean sailors who longed, as he did, for the days that had been. Life in the English navy was hard for sailors like John Ward—so hard that, as Sir Walter Raleigh remarked, men went “with as great a grudging to serve in his majesty’s ships as if it were to be slaves in the galleys.”

Conditions aboard even the best of the king’s ships were unsanitary and overcrowded. The Speedwell, for example, a thirty-gun man-of-war which was rebuilt at the beginning of the century, was about 90 feet long with a beam of less than 30 feet and a depth of about 12 feet. It carried a crew of 191, including 18 gunners, 50 small-arms men, 4 carpenters, and 3 trumpeters. (The Lion’s Whelp, in which Ward was serving, had a smaller crew, but then it was a smaller ship, probably only two-thirds the size of the Speedwell.) Hammocks were still something of a rarity, having only been introduced into the English navy in 1597 as “hanging cabins or beds . . . for the better preservation of [sailors’] health.” Most sailors shared a straw pallet with another man, although they did not usually occupy it at the same time: a two-watch system meant that one worked while the other was resting. They encountered other bedfellows, though: a Jacobean seaman rarely owned more than one set of clothes—typically a woolen Monmouth cap, a linen shirt, and a pair of knee-length canvas slops—which he kept on, waking and sleeping, until they were worn to rags. Clothes and bedding were riddled with lice and fleas.

The food at the beginning of a voyage wasn’t too bad; it might consist of biscuit, salt beef, meal, cheese, and beer. But the beef went bad, the beer turned sour, and the biscuit and meal attracted weevils. Dysentery and scurvy were both common.

These horrors lay in store for every mariner, whether he sailed as a pirate, a merchantman, or a member of His Majesty’s navy. But aboard a private vessel, discipline was relatively relaxed. When the pirate captain John Jennings fell for an Irish whore and installed her in his cabin, for example, his crew burst in on the couple and lectured him on his lax morals, which they blamed for a recent run of bad luck. He lashed out at them with a truncheon, at which they chased him round the deck with a musket. He only managed to save his life by barricading himself in the ship’s gunroom. Eventually tempers cooled and he resumed command. But history doesn’t record what became of his female companion.

That kind of behavior from the crew was inconceivable aboard a naval vessel, where discipline was rigid and the consequences of any kind of insubordination or disobedience were brutal. A minor transgression could earn the hapless sailor a spell “in the bilboes”—shackled by his legs as though in the stocks—or bound to the mainmast or capstan for hours on end with a heavy basket of shot tied round his neck. He might be ducked at the yardarm: “A malefactor, by having a rope fastened under his arms, and about his middle, and under his breech, is thus hoisted up to the end of the yard, from whence he is violently let fall into the sea, sometimes twice, sometimes three several times one after another.”

A refinement on ducking, reserved for more serious offenses, was keelhauling. A rope was rigged up from one yardarm to the other, passing under the keel, and the unfortunate offender was hauled up to one yardarm, dropped into the sea, and dragged slowly under the ship and up to the other. The experience of being half drowned was terrible enough, but much more serious damage was caused by being rasped over the razor-sharp barnacles that encrusted the ship’s bottom. Keelhauling was often a death sentence.

Keelhauling and ducking were cruel but relatively unusual punishments. By far the commonest penalty aboard ship was a thrashing. Minor offenders had to “pay the cobty” by being spanked on the behind with a flat piece of wood called a cobbing-board. More serious crimes were dealt with by the marshal or the boatswain with a painful whip known as the cat-of-nine-tails.

Corporal punishment was an integral part of seventeenth-century life in general. Husbands beat their wives; parents beat their children; masters and mistresses beat their servants; and employers beat their employees. But the unrelenting harshness of naval discipline was of a different order altogether. Remarking that sailors preferred to take their chances “in small ships of reprisal”—that is, in privateers or pirate ships—rather than serve the crown, the naval commander Sir William Monson (himself an ex-privateer) commented that this was because of “the liberty they find in the one, and the punishment they fear in the other.”

Monson had a point. But he glossed over another reason sailors preferred privateering. In the Royal Navy a Jacobean seaman’s pay was ten shillings per lunar month before deductions (the navy calculated sailors’ pay on the basis of a twenty-eight-day month right up until the beginning of the nineteenth century). That wasn’t bad; but the crew of a privateer out on a cruise against the Spanish shared one-third of the prize money among them, and that could easily amount to ten or fifteen pounds, rather more than a top lawyer’s highest fee, for a voyage lasting only a couple of months. Little wonder that professional sailors, especially those who had prospered as privateers before England’s peace with Spain, were less than happy to swap good money and relative freedom as a privateer for punishment and privation in the navy. Or that they wished, as John Ward wished, for the days that had been, “when the whole sea was our empire.”