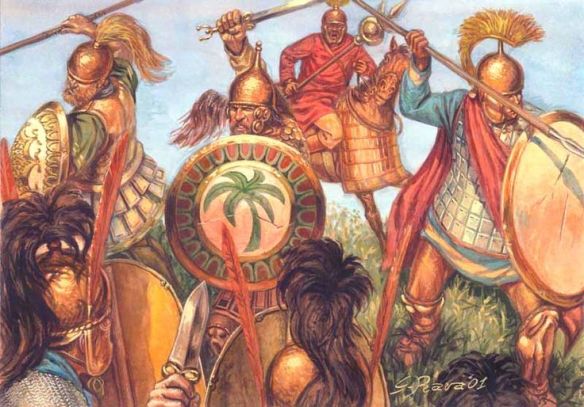

On the whole, the professional soldier was worth his salt until the first war with Rome was over, and he would, by the time of the next bout, supply the core of Carthaginian armies. Unlike a Roman army, therefore, a Carthaginian army was a heterogeneous assortment of races, and in the period of these two wars we hear of Libyans from subject communities, Numidians and Moors from the wild tribes of the northern African interior, Iberians, Celtiberians and Lustianians from the Iberian peninsula, deadeye shooters from the Balearic Islands, Celts or Gauls, Ligurians, Oscans and Greeks, a ‘who’s who’ of ethnic fighting techniques. The army that Hannibal led against the Romans, for instance, differed more from Hellenistic and Roman armies, based as they were around heavily equipped infantry either in a phalanx or a legion, than the latter two did from each other.

Hannibal’s brother Hasdrubal did leave Spain to reach northern Italy in 207, but brought no help to his increasingly beleaguered elder brother in the south. Hannibal was so circumscribed by Roman armies that the consul Gaius Claudius Nero could lead an élite force northwards to join his colleague Marcus Livius Salinator facing Hasdrubal. They destroyed the new invasion at the river Metaurus, just inland from the Adriatic. Nero took Hasdrubal’s head back to deliver to his brother: Carthaginians might remember how in 309 the Syracusans had sent the head of Hamilcar son of Gisco over to Agathocles.

Hannibal hung on in the very south of Italy for four more years. Now he probably hoped that, as long as he stayed, he would keep Africa safe from invasion; indeed old Fabius Maximus opposed Scipio’s project for this very reason. Moreover in 205 Italy was yet again invaded by a Barcid, Hannibal’s surviving brother Mago. Yet by landing in Liguria Mago gave himself no better chance than Hasdrubal of reaching their brother; eventually his invasion was crushed and he himself mortally wounded. By then Scipio was conquering Libya, and Hannibal was finally called home.

The defence of North Africa was first led by the Barcids’ ally Hasdrubal son of Gisco and Syphax, king of Numidia. Originally king of the western Numidian Masaesyli, Syphax had united the country by driving out the would-be king of the Massyli – Masinissa – and had married Hasdrubal’s daughter, the cultured and beautiful Saponibaal (in Latin, Sophoniba, often misrendered `Sophonisba’). They failed to repel Scipio, who landed near Utica in 204 to be joined by Masinissa. After a lengthy period of insincere negotiations, he destroyed their camps and armies in a night attack early in 203, then defeated their new armies inland on the Great Plains near Bulla in the upper Bagradas valley. With Syphax captured, Masinissa was recognised by Scipio as king of all Numidia – though the new king was forced to renounce his new wife Sophoniba, whom he married after falling in love at first sight (or so the tale was told). At his command, she took poison, completing the romantically tragic story.

The last two years of the war limited it to North Africa. After the Great Plains, the Carthaginians sought and accepted Scipio’s peace terms, which removed Carthage’s military and naval capabilities, annexed Spain, and exacted a large indemnity, but left her home territories intact. Peace was then confirmed at Rome, but meanwhile the Carthaginians had sent Hannibal and Mago a recall – and when Hannibal landed at Hadrumetum with his veterans, to be joined by the survivors of his brother’s army, he continued to act as though the peace did not apply to him. Nor, it seems, did his countrymen object, causing Scipio in turn to renew operations inland.

It took Hannibal most of 202 to build up and train a new army, so that only in October did he set out to find Scipio. Before the last battle, the two leaders held a famous personal meeting near Naraggara, 40 kilometres west of Sicca, which resolved nothing but let each get to know the other. Next day, probably 19 October, Scipio defeated his opponent in the so-called battle of `Zama’ – a misnomer perpetrated by Nepos – by routing his elephant corps and cavalry, then beating down each of Hannibal’s three rather disconnected battle lines in turn. The battle was still in the balance, with Hannibal’s third line of mainly Bruttian veterans fighting Scipio’s legionaries (most of them survivors of Cannae), when the Roman and Numidian cavalry returned to strike the veterans in the rear, a reversal of Hannibal’s coup at Cannae. Hannibal got away with a few horsemen and told his countrymen to seek peace.

Scipio’s new terms were rather harsher: no Carthaginian navy except ten ships, no overseas wars at all and none in Africa without Rome’s permission, an indemnity of 10,000 talents over fifty years (60,000,000 Greek drachmas or Roman denarii), and – a clause which would bring future trouble – Masinissa was entitled to the lands held by his ancestors. But Carthage remained intact, independent and in control of Libya: in fact Scipio surveyed and confirmed her existing borders. Hannibal was left untouched.

In 201, as his last act in Africa Scipio anchored the navy of Carthage, large ships and small, in sight of the city and burned them: the symbolic end of Carthage as a great power. From then on she had to make her way in a changed world.

HANNIBAL’S WAR: AN ASSESSMENT

Could Carthage have won the Second Punic War? Rome’s military strength is often pointed to as the critical factor for victory – as a contest of Goliath versus David in which Goliath won. Another argument, less popular today though going back to Polybius, is that a nation of comfortable merchants who paid others to do their fighting had no chance against a tough farming people who each year went out to inflict massive damage on their foes. In reality, as mentioned above, Carthage’s military strength from the start was at least equal to Rome’s. Even in 207, when some 130,000 troops were still serving in Roman armies from Italy to Spain, Carthage’s armies as reported by Polybius and Livy totalled as much as 150,000. Moreover her revived navy grew to well over 100 quinqueremes. The unwarlike-merchants picture is just as flawed: the ruling élite was as much, or more, a landowning class accustomed to military as well as naval leadership. Roman society, in turn, was already commercially developed by 264 and still more so by 218, while the Roman authorities were alert to the importance of trade: so the fuss with Carthage in 240 over the arrested Italian traders showed, and then the war with the Illyrians in 229 over Illyrian piracy.

The war might, arguably, have been won had Hannibal marched directly on Rome after his crushing victory at Lake Trasimene in 217, or after Cannae the year after. He might have retrieved the situation as late as 207, if he had made a better effort at leaving Apulia to join forces with his brother (as Hasdrubal was expecting). A less noticeable point, but just as important, is that large reinforcements sent to Italy by sea – not to Spain or Sicily, as they were – could have made the difference even as late as 212; Hannibal’s only reinforcements were 4000 men and 40 elephants in 215. Indeed, had Mago in 205 brought his 25,000 troops and elephant corps to Bruttium, the Romans might not have authorised Scipio to go to Africa, although by then the best that Carthage could hope for would be a compromise peace.

As for the Romans, they may have thrown away their best chance for an early victory, saving tens of thousands of lives, by electing to abort the planned invasion of Africa in 218 while continuing the expedition into Spain. An African invasion would have met no Carthaginian general of Hannibal’s abilities (nor were Greek mercenaries in service by now), while there was as yet no navy able to prevent a Roman blockade of the city by sea as well as land. The Carthaginians’ greatest weakness – or inhibition – was over an invasion of their home territories, as both Agathocles and Regulus had shown and as Scipio proved. It took Scipio only two victories in one year to bring them to terms, even if Hannibal’s return then required a third before peace finally came.