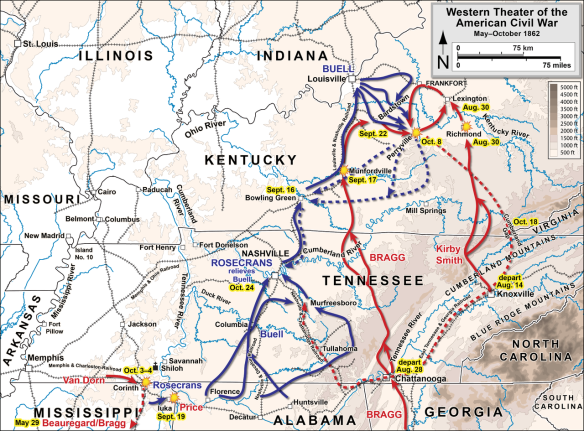

Buell was at last conforming to Washington’s wishes and during early October appeared in the vicinity of Bragg’s army at Bardstown. He concentrated 60,000 men, to the Confederates’ 40,000. They were now, in Bragg’s temporary absence, under the orders of Bishop Leonidas Polk, who led his men to the small town of Perryville, south of Louisville. What drew him there was a need for water, the Southern summer having dried up the streams. A prolonged drought had left the Chaplin River a string of stagnant pools. As that was the only water available, both sides wanted it. Polk got to it first but was soon attacked by the advance guard of Buell’s army, commanded by the up-and-coming Philip Sheridan. Sheridan was aggressive and directed his division’s efforts to such effect that it defeated Polk’s army and advanced into the streets of Perryville, driving its remnants before them. At this stage, Buell should have completed what was turning into the victory of Perryville and destroyed, with reinforcements, what remained of Bragg’s army. By the meteorological accident of acoustic shadow, however, no sound of the battle raging in Perryville reached the ears of anyone else under Buell’s command. He therefore failed to march to Sheridan’s assistance, though as darkness fell the Confederate line was defended by only a single brigade which would have dispersed if attacked aggressively. Next morning, when Buell positioned his army for a general advance, the ground was empty. Bragg had during the night decided he was beaten and had led his army away.

Perryville was an all-too-typical Civil War battle in its lack of decision, despite high casualties on both sides. The indecisiveness of battles is one of the great mysteries of the war. In the East, particularly from 1864 onwards, it was largely explained by the recourse to digging, which produced earthworks from which it was almost impossible to expel the enemy. In the West, by contrast, particularly in the earlier years, earthworks were less commonly constructed. The explanation therefore seems to lie in two unconnected factors: the lack of a military means, such as large cavalry forces or mobile horse artillery, that could deliver a pulverising blow, and the remarkable ability of infantry on both sides to accept casualties. Casualties at Perryville—4,200 Union and 3,400 Confederate—were certainly high, but neither side seemed shaken. An eyewitness, Major J. Montgomery Wright of Buell’s army, describes the strange phenomenon of the acoustic shadow. Riding as a staff officer on a detached mission, he “suddenly turned into a road and therefore before me, within a few hundred yards, the battle of Perryville burst into view, and the roar of the artillery and the continuous rattle of the musketry first broke upon my ear…. It was wholly unexpected, and it fixed me with astonishment. It was like tearing away a curtain from the front of a great picture…. At one bound my horse carried me from stillness into the uproar of battle. One turn from a lonely bridlepath through the woods brought me face to face with the bloody struggle of thousands of men.” Major Wright witnessed the effect of the struggle on one group, which suggests that the battle was having a decisive effect upon them: “I saw young Forman with the remnant of his company of the 15th Kentucky regiment, withdrawn to make way for the reinforcements, and as they silently passed me they seemed to stagger and reel like men who had been battling against a great storm. Forman had the colours in his hand, and he and several of his little group of men had their hands upon their chests and their lips apart as though they had difficulty in breathing. They filed into a field and without thought of shot or shell they lay down on the ground apparently in a state of exhaustion.”1 Yet despite such efforts the Union line did not break, nor did the equally punished Confederate. Bragg, who rightly recognised he was outnumbered, swiftly decided to withdraw during the night of October 8 and fell back to Knoxville and Chattanooga, abandoning his invasion of Kentucky altogether. The Southern press, and several of his generals, seethed with dissatisfaction; Bragg was called to Richmond to account for his failure, but he had a friend in Jefferson Davis, who accepted his explanations and allowed him to continue in command.

Bragg’s abandonment of the attempt on Kentucky completed a general Confederate failure on the central front in the West. Just before Perryville, Generals Price and Van Dorn had been defeated by the Union general Rosecrans at Corinth in Mississippi. It followed another Confederate defeat at nearby Iuka. Grant, who was engaged in the campaign at a distance, had hoped to trap the Confederates either at Corinth or Iuka and was disappointed not to do so. He blamed Rosecrans, for a movement of his troops he thought dilatory, though the recurrence of acoustic shadow may have played a part. For whatever reason, however, the Confederates had failed in their efforts to reverse the balance of power both in Kentucky and Tennessee, in what proved to be the last unforced Confederate offensive west of the Appalachians. As the fighting died down, Grant gathered his forces to renew his campaign against Vicksburg. The citizens of Cincinnati and Louisville relapsed into calm, after what had been some disturbing weeks. Though it was not realised in Richmond, the failure in the West was a grave blow to the Confederacy, reducing their range of strategic options to the well-worn pattern of keeping alive Union fears of an advance against Washington or feints at Pennsylvania and Maryland, theatres where the North enjoyed permanent advantages. The drive into Kentucky and threats against Tennessee were the only imaginative moves made by the Confederacy throughout the war; their failure and the failure to repeat them confirmed to objective observers that the South could now only await defeat. It might be long in coming, but after the end of 1862 it was foreordained and inevitable.

There were objective observers. Two were Karl Marx and Frederick Engels, then in exile in England, where in March 1862 they composed an analysis of the progress of the Civil War of quite remarkable prescience. Marx and Engels’s interest in the Civil War was not political. As revolutionaries they hoped for nothing from the United States. It was simply that as men with a professional interest in warfare and the management of armies they could not prevent themselves from studying military events, and prognosticating based on their lessons. Marx concluded that, following the capture of Fort Donelson, Grant, for whom he had formed an admiration, had achieved a major success against Secessia, as he called the Confederacy. His reason for so thinking was that he identified Tennessee and Kentucky as vital ground for the Confederacy. If they were lost, the cohesion of the rebel states would be destroyed. To demonstrate his point, he asked, “Does there exist a military centre of gravity whose capture would break the backbone of the Confederacy resistance, or are they, as Russia still was in 1812 [at the time of Napoleon’s invasion], unconquerable without, in a word, occupying every village and every patch of ground along the whole periphery.”

His answer was that Georgia was the centre of gravity. “Georgia,” he wrote, “is the key to Secessia.” “With the loss of Georgia, the Confederacy would be cut into two sections which would have lost all connection with each other.” It would not be necessary to conquer the whole of Georgia to achieve that result, but only the railroads through the state.

Marx had foreseen, with uncanny insight, exactly how the decisive stage of the Civil War would be fought. He was scathingly dismissive of the Anaconda Plan, and he also minimised the importance of capturing Richmond. To that extent, his foresight was defective. The blockade, a major element of the Anaconda strategy, was crucial to the defeat of the Confederacy, and it was indeed the capture of Richmond that brought the war to an end. In almost all other respects, however, Marx’s analysis was eerily accurate, testimony to his grisly interest in the use of violence for political ends. The analysis was published in German, in Vienna, in the review Die Presse. It may not have been noticed in the United States.

Marx, who had the keenest eye for strategic geography, did not discuss the importance of Tennessee and Kentucky as a weak spot in the defences of the Union. Materialist as he was, he had already assured himself that the vastly preponderant industrial and financial power of the North guaranteed its victory. He made insufficient allowances, however, for the necessity of fighting for that outcome and for how relentless the struggle would be.