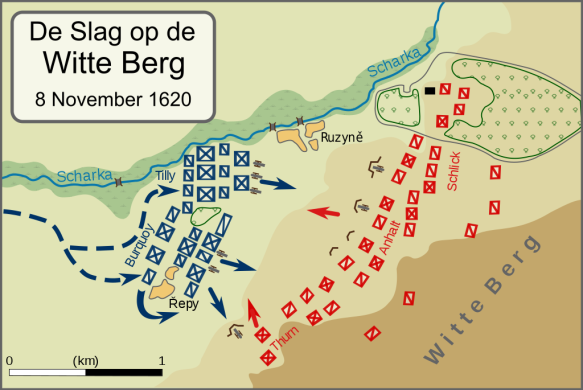

The coming battle was the first major action of the war and proved to be the most decisive. Anhalt’s position was relatively strong. The White Mountain ridge, taking its name from chalk and gravel pits, ran north-east to south-west for about 2km, rising about 60 metres from the surrounding area. It was strongest at the northern (right) end where the incline was steepest. This end of the ridge was covered by a walled, wooded game park containing the Star Palace, a small pavilion where Frederick and his wife had stayed prior to their triumphal entry to Prague a year earlier. The marshy Scharka stream lay about 2km in front of his position, but was deemed too far from the hill to be defended.

Anhalt had 11,000 foot, 5,000 cavalry and 5,000 Hungarian and Transylvanian light cavalry. He wanted to entrench the entire length of the ridge, but his mutinous soldiers were exhausted and said digging was only for peasants. Frederick went on to Prague, persuading the Estates to find 600 talers to buy spades, but it was too late and the soldiers managed to make only five small sconces. Most of the artillery had not caught up, and the ten cannon with the army were distributed along the line. Johann Ernst of Weimar held the Star Palace with his infantry regiment, while the rest of the Confederate army drew up along the ridge in two lines in the Dutch manner, interspersing cavalry squadrons in close support between the infantry battalions. The light cavalry were dispirited, having been surprised earlier that night and most were positioned fairly uselessly as a third line in the rear, while some covered the extreme right. Despite obvious shortcomings, Anhalt remained optimistic, believing the enemy would simply stall in front of his position as at Rakovnic, and Frederick remained in Prague to eat breakfast.

Thick fog obscured the imperial-Bavarian approach on the morning of Sunday 8 November. The advance guard secured the two crossings over the stream, followed by the rest of the army that deployed from 8 a.m. The Liga regiments drew up on the left opposite the northern end of the ridge, while Bucquoy’s Imperialists took station on the right. Together, they had 2,000 more men and two more cannon than their opponents, and they were in better spirits. Both halves of the army deployed in the Spanish fashion, grouping the 17,000 foot into ten large blocks, accompanied by small cavalry squadrons.

The commanders conferred while their men took up their positions and heard mass. Bucquoy wanted to repeat the earlier trick and slip past to Prague, but Maximilian and Tilly were convinced it was time for the decisive blow. The dispute was allegedly resolved by Domenico bursting in and brandishing an image of the Madonna whose eyes had been poked out by Calvinist iconoclasts. If this is true, it was a calculated act, because the Carmelite had found the icon in a ruined house over three weeks before. The Catholic troops were elated when they received the order to attack; they were tired of chasing the Confederates across Bohemia and savoured the prospect of plundering Prague.

The artillery had been firing for some time to little effect. At about fifteen minutes after midday all twelve guns fired simultaneously to signal the advance. The Imperialists had less ground to cover to reach the ridge than the Bavarians who also faced a steeper climb. Anhalt decided on an active defence, sending two cavalry regiments down the slope to drive off the imperial cavalry screening the flanks of the Italian and Walloon infantry spearheading the assault. Thurn’s own infantry regiment then moved down to engage the enemy foot as they laboured up the slope. Seeing their own horsemen retiring, the Thurn regiment fired a general salvo at extreme range and fled. Anhalt’s son tried to retrieve the situation with his own cavalry regiment from the Confederate second line, his men using their pistols to blast their way into one of the imperial tercios. For a brief moment it looked as if the Confederates might yet snatch victory, but more imperial horse came up, and even Bucquoy arrived, despite his earlier wound, to rally the infantry. Anhalt junior was captured and within an hour of the main action starting the Confederate horse were in full retreat, many units pulling out of the line without even engaging the enemy. The Bohemian foot followed soon after, while the Hungarians fled, some dismounting in order to escape through the vineyards covering the way to Prague. Despite claims of their being spooked by Domenico’s sudden appearance through the smoke, the panic stemmed from reports that Bucquoy’s Polish Cossacks had ridden round the south-west end of the ridge and were already at the rear. Schlick’s Moravians on the right lasted longer, largely because of the time it took Tilly to reach them, but they too gave way around 1.30 p.m. A few survivors resisted for another half hour in the Star Palace before surrendering.

Frederick stayed in Prague all day and was tucking into lunch when the first fugitives arrived. Many drowned in the Moldau in their desperation to escape. The imperial-Bavarian army lost 650 killed and wounded, mostly to young Anhalt’s brave attack. The Confederates left 600 dead on the field, with a further 1,000 strewn on the way to Prague, as well as 1,200 wounded. The losses were severe, but most had escaped. Prague was a large, fortified city and it was unlikely the enemy could besiege it with winter approaching. It was here that Tilly’s strategy of relentless pressure paid dividends, transforming a respectable battlefield success into a decisive victory. Already weakened by Tilly’s vigorous campaign, Confederate morale collapsed. Even Maximilian was surprised at the extent of the enemy’s demoralization, expecting defiance when he summoned Prague to surrender. Confederate leadership was utterly pathetic. Tschernembl and Thurn’s son, Franz, tried to organize a defence on the Charles Bridge to stop the Bavarians crossing the river. Frederick hesitated, but Anhalt and the elder Thurn thought the situation hopeless. Queen Elizabeth, heavily pregnant with her fifth child, left early the next morning. Her husband feared angry citizens might prevent him escaping if he took the crown with him, so he left it behind, along with his other insignia and numerous confidential documents, and joined the refugees streaming eastwards out of the city.

Collapse of the Confederation

Imperialists were already entering the western side of the city, catching the tail of the royal baggage train. Many Confederates were still loitering, demanding their back pay, but they dispersed once Maximilian granted them amnesty on 10 November. Those foolish enough to remain were murdered over the next few days. The city was stuffed full of valuables, cattle and other property brought there for safekeeping prior to the battle and now abandoned in the precipitous retreat. Along with empty mansions and houses, it was too tempting for the victorious troops who began seizing what they found in the streets, then breaking into homes, and finally robbing with violence. ‘Those who have nothing, fear for their necks, and all regret not taking up arms and fighting to the last man.’

Under these conditions, further pursuit was impossible. The winter was also exceptionally cold, with even the Bosporus said to have frozen over. Mansfeld still held most of western Bohemia, while Jägerndorf was in Silesia and Bethlen in Hungary. Yet nothing could slow the collapse of Frederick’s regime as moderates distanced themselves from the revolt. The Moravian Estates already paid homage to Ferdinand at the end of December. Frederick fled east over the mountains into Silesia in the middle of November, but was given a frosty welcome by a population angry at his perceived Calvinist extremism. Fearing the Saxons would block his escape to the north, Frederick hurried on down the Oder into Brandenburg in December, leaving the Lusatians and Silesians to surrender to Johann Georg after prolonged negotiations completed in March 1621.

Bethlen had finally renounced his truce with the emperor on 1 September, advancing again with 30,000 horsemen to overrun Upper Hungary and retake Pressburg, where he intended to hold his coronation with the St Stephen’s crown he had captured the year before. Most of the Polish Cossacks arriving during 1620 had been attached to Dampierre’s command and deployed to cover the harvest against Transylvanian raiders. A Liga regiment arrived at the end of September 1620, as well as Croats and the private retainers of Magyar magnates tired of Bethlen’s depredations. The Inner Austrian Estates mobilized 2,500 men, while their Lower Austrian counterparts sent a Protestant regiment that had not joined the Confederate army. Dampierre advanced to disrupt Bethlen’s coronation, and though he was to be killed on 9 October he had managed to burn the Pressburg bridge, denying access to the south side of the Danube. Bethlen sent another 9,000 troops to help Frederick, but these arrived too late for White Mountain and retreated rapidly through Moravia in November.

Though the grand vizier ratified the alliance agreed with Frederick in July, it became clear that the sultan was only using this to pressure Ferdinand to adjust the 1606 truce. News of White Mountain reached Constantinople in January, removing any doubts about the wisdom of avoiding a breach with the emperor. Meanwhile, the Ottoman pasha of Buda seized the Hungarian border town of Waitzen long claimed by his master. This alarmed the Magyar nobility, exposing the consequences of their internecine struggle and Bethlen’s inability to protect them from the Ottomans. The leading families either declared for Ferdinand or at least joined the French ambassador in pressing Bethlen to reopen talks at Hainburg in January 1621.