Serious American conversion discussion of air attacks against Japan predated Pearl Harbor by at least two years. In January 1940 a retired naval officer delivered sensitive documents to the Navy Department for unofficial discussion. The messenger was Bruce Leighton, a former naval aviator representing Intercontinent Corporation and Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company (CAMCO), which operated in China.

Leighton met with Marine Corps Major Rodney Boone of the Office of Naval Intelligence. They proposed “an efficient guerrilla air corps” to assist China, which had been fighting Japan since 1937. The proposed American aid would go to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek’s Nationalists, as the Chinese Communists lacked the strength and alliances to field an air force.

Eight months later, in September 1940, Lieutenant Commander Henri Smith-Hutton, the U.S. naval attaché in Tokyo, reported that Japan’s “fire fighting facilities are willfully inadequate. Incendiary bombs sowed widely over an area of Japanese cities would result in the destruction of the major portions of the cities.” The attaché noted that the few bomb shelters also were inadequate, and he was preparing a list of “important bombing objectives,” including military, government, and industrial targets. “Willfully inadequate” was an apt description. No less an authority than Billy Mitchell had noted Japan’s sustained vulnerability to fire bombing seventeen years before.

During the winter of 1940–41 the Roosevelt administration approved formation of a clandestine fighter group to aid China, staffed by discharged U.S. military personnel. Anticipating eventual Allied bombing of Japan, China’s Chiang Kai-shek had bomber bases constructed in the remote Chengtu area about that same time. A year passed before the First American Volunteer Group (AVG) became operational over China and Burma, entering history as the fabled Flying Tigers, led by former U.S. Army officer Major (later Major General) Claire Chennault. In the months after Pearl Harbor, the AVG’s shark-nosed P-40s presented the most effective opposition to Japanese airpower on the Asian mainland.

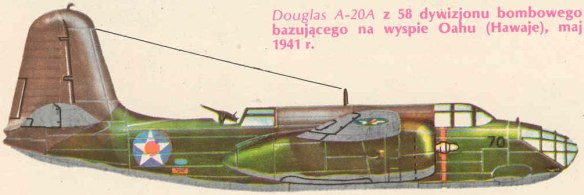

A second AVG [1] was formed with the intention of bombing Japan. Equipped with twin-engine Lockheed Hudsons and Douglas Bostons, the unit’s 440 pilots and staff began departing the United States in November 1941. US reclaimed the bombers destined for the 2nd AVG since they came from British contracts (33 Hudsons and 33 Bostons). Over 70% of the US-produced combat aircraft destined for China in 1941 came from ex-British contracts (if you include the Vultee P-66 Vanguards we took from the Swedes). However, by the time most of the men and some of the aircraft reached Asia, America was fully at war and covert operations were unnecessary.

Other prewar plans had envisioned bombing operations against Japan from Wake Island, Guam, the Philippines, and the China coast. With those options rapidly lost in 1941–42, more ideas emerged.

In March and April 1942, the Army Air Forces sent thirteen heavy bombers to China with the mission of attacking the Japanese homeland. They were led by Colonel Caleb V. Haynes, who fetched up in India, awaiting events as his progress was barred by both the Japanese and Nationalist Chinese. The Japanese surge into Burma posed logistics problems for Haynes’s unit, and Chiang Kai-shek worried that attacking Japan from eastern China would invite retaliation against the population. However, “C.V.” Haynes remained in Asia, becoming Chennault’s 14th Air Force bomber commander.

Meanwhile, the third plan went ahead. It was dubbed Halpro (for Halvorsen Project), led by colorful, hard-drinking Colonel Harry A. Halvorsen, who had helped develop air-to-air refueling in 1929.

Halpro’s thirteen B-24 Liberators departed Florida in May 1942, winged across the South Atlantic from Brazil, and headed for China via North Africa. But they were side-tracked in Egypt, where the bombers were needed owing to pressure from the German Afrika Korps, which dominated the campaign for control of North Africa. Thus, the B-24s were sent to bomb Ploesti, a major source of Nazi oil in Romania. The mission was launched from Egypt in June 1942 with a notable lack of success. Fourteen months later a vastly larger mission was undertaken, pitting 177 Libya-based Liberators against several Ploesti refineries and incurring spectacular bomber losses.

After the Doolittle Raid, and after Haynes and Halpro faltered, the next proposal arose within China itself. In July 1942, shortly after disbanding the AVG, Chennault informed Army Air Forces chief Hap Arnold of the desire to increase the new China Air Task Force to forty-two bombers and 105 fighters supported by sixty-seven transport aircraft. Chennault claimed that with such an assembly he could drive the Japanese air force from China skies, paralyze enemy rail and river traffic in China, and bomb the home islands. Furthermore, with 100 P-47 Thunderbolt fighters and thirty B-25 Mitchell bombers, he pledged to destroy “Japanese aircraft production facilities.”

Nor was that all. Three months later Chennault assured Roosevelt that with 105 of the latest fighters and forty bombers (including a dozen B-17s or B-24s) he would “accomplish the downfall of Japan . . . probably within six months, within one year at the outside.” He added, “I will guarantee to destroy the principal production centers of Japan.”

That a professional airman like Chennault truly believed such puffery is hard to accept. Among other things, he knew from experience that the Japanese had failed to destroy Chinese cities with far larger forces over a period of years. But however his grandiose claims were received in Washington, he remained the U.S. air commander in China for the rest of the war.

Subsequently it took hundreds of B-29 Superfortresses fourteen months to realize Claire Chennault’s fantasy. In fact, when Chennault wrote Arnold that summer of 1942 the Superfortress was not yet a reality.

[1] For those with an interest in the 2nd American Volunteer Group and the idea of a preemptive strike on Japan, I would like to recommend the work of Michael Schaller. In Chapter 4, American Air Strategy and the Origins of Clandestine Warfare, in his U.S. Crusade in China, 1938-1945 (1979), he describes in some detail U.S. plans to sponsor a covert attack upon Japan. Material in the chapter first appeared in American Quarterly (Spring 1976). Dr. Schaller provides interesting material for interpreting the U.S. relationship with China between 1938 and 1945. He examines that relationship over a longer period of time in his The United States and China in the Twentieth Century (1979).

Stilwell’s Mission to China also provides an interesting insight into who was the original architect of this light bombardment unit. CAMCO VP Richard Aldworth was the one who actually drafted the Table of Organization and Equipment for the 2nd AVG and submitted it via letter to T.V. Soong on 17 August 1941, which Chennault subsequently approved via radiogram to Soong on 29 September 1941. Most sources that mention the 2nd AVG (and there aren’t many) indicate the TO&E called for 82 pilots and 359 technicians.

Intriguing that the DB-7s were originally planned to be flown by Chinese pilots. Was the bomb group to be integrated along the lines of the later Chinese-American Composite Wing?

2nd AVG Commander Royal Leonard.

In the Chennault papers at Stanford, he discovered a draft telegram of 3 November 1941 from Chennault to R.C. Chen, of China Defense Supplies in Rangoon, that he is sending a CNAC pilot, Royal Leonard to the U.S. to ferry bombers to China. He is to arrive in D.C. on or about 20 December.

He had the confidence of Generalissimo and Madame Chiang, as he had been their personal pilot. He flew under fire of Communists and Japanese alike in the Boeing 247 and DC-2 during from 1935-1941, carrying out reconnaissance missions and supply drops, in addition to executive transport. Madame Chiang actually placed him in charge of bombardment for the Chinese Air Force when the Sino-Japanese War broke out in earnest in 1937, and in this role he flew as an observer on bombing missions with his CAF charges.

Chennault also recognized his ability in this area, as he called upon Leonard (along with Julius Barr and Ernest Allison) to evaluate potential pilots for the ad-hoc 14th Volunteer Bombardment Squadron. Later during the AVG period, when Chennault was planning a bombing raid on Kyushu island using the SB-3 bombers left by the Soviet mission, he wanted Leonard to lead the mission as he was the best navigator in China.

Leonard was a former Air Corps pilot (actually trained by Chennault at Brooks Field) who was expert in navigation (China in particular), night/instrument flying and had been under fire. These were rare commodities to be found in China in 1941.

When the plans for the SAVG fell through, Leonard re-upped with Pan Am to fly for its subsidiaries, first flying a B-25 from the US to India for Pan Am Ferries, and then rejoining CNAC to fly the Hump for the ATC. He did this until mid-1943

Leonard’s I Flew For China (written in 1942 and not so much an autobiography as an account of his prewar years in China) has the following passage:

When I sailed from China for the United States, Chennault and I had our own plans for the prosecution of the war against Japan already set. I was to proceed to collect a section of pilots, recruiting them in the United States by the same methods that Chennault had used. These were to be solely bombardment men. I was to work with them and train them for flying over Chinese terrain and the sea. The United States government had promised us at least twenty-seven new light Hudson bombers with a 2000-mile range under an effective bomb load. The bombing of Honolulu [7 Dec 1941], among other things, also blew our plans sky-high. Our proposed line of flight, to Manila, then to Guam (which was supposed to have a new landing field completed by the time we were ready to go), and on to China, was blasted. Our fondest dream, the bombing of Nagasaki, was not then to come true.