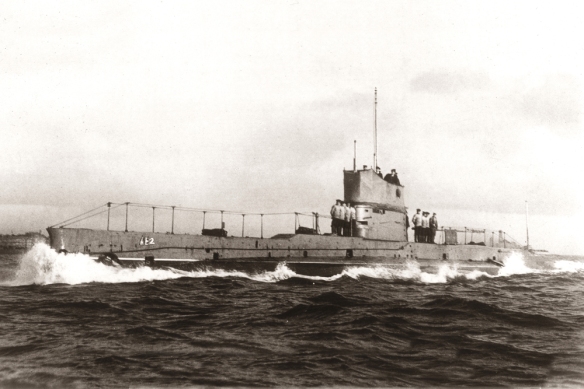

The loss of HMAS AE2 in Turkish waters was the final blow for the Australian submarine fleet after its sister sub AE1 had been lost while patrolling off New Guinea in 1914. The wreck of the AE2 was found by divers in 1998. AWM

Undeterred by the failure of British submarines to penetrate the Dardanelles, Lieutenant Harry Stoker, front row centre, bravely steered his little HMAS AE2 submarine through to the Sea of Marmara, aiming to torpedo enemy ships transporting Turkish reinforcements to Gallipoli. AWM

It was 25 April 1915 when this battle got under way-the same day Anzac troops landed on the western beaches of the Gallipoli peninsula. The troops planned to attack Constantinople (Istanbul) overland fighting their way up this peninsula, but there was also a sea route to Constantinople along the Dardanelles Strait between the peninsula and the mainland which passes through the Narrows and into the wider Sea of Marmara.

HMAS AE2 was bravely trying to help with that bloody battle by sneaking around the eastern side of the same peninsula, attacking the Turks from the rear by destroying transports before they could ferry more troops across the Sea of Marmara and also distracting any warships shelling Allied troops landing on those beaches.

The hazardous mission was directed by top British naval officers anxious to stab Turkey in the back. Admiral John de Robeck told Stoker that if AE2 got through, then `there is nothing we will not do for you’. Stoker was ordered to sink any mine-laying ships he saw in the Narrows and, as the landings were due at dawn the next day, to `generally run amok’ around Cannakale to cause maximum disruption to the Turks.

It was a tall order and a dangerous one for a tiny submarine and inexperienced crew in the narrow confines of enemy-infested waters.

Leaving her base near the mouth of the Dardanelles, AE2 started early so she could reach the entrance to the mighty waterway at 2.30 a. m. under cover of darkness. At first AE2 was able to sail along on the surface under cover of darkness, sailing between the land either side where lights could be seen from fortifications, streets and the homes of Turkish families. Stoker noted that the moon had just set and searchlights played across the dark waters, but: `As the order to run amok in the Narrows precluded all possibility of making the passage unseen, I decided to hold on the surface as far as possible’.

Then, at 4.30 a. m., about the same time as the first of the Anzacs landed on the beaches under fire from the Turks, the enemy guarding the Dardanelles spotted the sub. Stoker said `a gun opened fire at about one and a half miles [2-kilometre] range . . . I immediately dived and . . . proceeded through the minefield’.

So far so good. AE2 dodged that first enemy fire and sailed submerged, covering an impressive 10 kilometres of the 60-kilometre channel. It got lighter until by 6 a. m. AE2 reached Chanak, the narrowest part of the strait, and Stoker saw the first target he could `run amok’ with-the Turkish gunboat Peyk I Sevket. There might have been enemy ships all around him, but Stoker coolly lined up the Turkish boat, fired off a torpedo and hit the bull’s-eye before escaping.

The Turks, alerted to the immediate presence of a deadly submarine in their midst, now hunted AE2 in earnest. Forts on either side sprang into action. Heavy fire opened up from Fort Chemenlik at Cannakale and from Kilitbahir on the other side of the Narrows, while gunboats and destroyers criss-crossed the surface.

Luckily the shore batteries were too far away for accurate shooting, but in the excitement Stoker ran his submarine aground directly under a Turkish fort, which luckily was unable to lower its guns to range on AE2. After four anxious minutes exposed on the surface, the submarine worked itself off the shore while shells fell all around it, and slid back into deeper water.

Stoker immediately submerged and continued bravely weaving his way through a web of lines tethering the mines that filled the waters of the Dardanelles, trying not to hit the bottom but nevertheless grounding from time to time, and bouncing towards the surface now and then, yet making steady progress towards the Sea of Marmara.

Soon after another grounding and a return towards the surface, Stoker realised he had passed through the Narrows successfully-but he was surrounded by enemy ships.

When his periscope was sighted by a Turkish battleship firing over the peninsula at British positions, there was only one thing he could do: dive to the bottom.

By this stage many Turkish ships were on the lookout for AE2. They could not find the submarine’s position when it was submerged and it could attack only when it surfaced. On the other hand, submarines passing through the Dardanelles needed to surface frequently to take accurate bearings from landmarks, otherwise they risked running aground. Feeling he had sufficient data for his course, Stoker now headed the AE2 down the straits past Nara Burnu at some depth before he risked further observations at periscope depth.

Coming back up once more, Stoker saw they were well past the Narrows, but the Turks saw him too and the chase resumed. Diving deep again, the next time AE2 surfaced Stoker saw straight ahead two Turkish tugboats with a cable stretched between them to catch the submarine’s conning tower.

Stoker took AE2 to the bottom and settled the vessel there with engines off. They did not have enough power left in the batteries to get through to the Sea of Marmara, and recharging them would require running on the surface under diesel power.

It was 8.30 a. m. on 25 April 1915. As the Anzacs tried to advance up the cliffs of Gallipoli, these sailors of the Royal Australian Navy were almost through the Dardanelles and into the Sea of Marmara where they could really have a go at Johnny Turk.

Stoker spent the rest of that first Anzac Day sitting on the bottom, hoping the ships searching for him would give up. It was Sunday so, at about the time most Christians would have been going to church back home, Stoker held prayers then gave the crew a chance to sleep.

Overhead they could hear the Turks looking for them and later something being towed from the surface hit the side of the vessel. Leaks were bringing significant amounts of water into the bilges and this water, if pumped out, could reveal their position because it contained large amounts of oil. All day the crew worked carrying water to other parts of the submarine.

At 9 p. m. Stoker finally brought AE2 back to the surface, where he saw his strategy of laying low and hiding had paid off-no enemy ships were in sight. They had spent more than sixteen hours under water. The air become so stale in the submarine that a match would not burn for more than a fraction of a second.

The crew were hurried up top for gulps of fresh air and Stoker restarted the diesel engines, moving ahead to charge the batteries.

Travelling through the night and against all odds, Stoker and his crew made it through the Dardanelles and into the Sea of Marmara by the early hours of Monday 26 April-a major breakthrough. The AE2’s wireless operator repeatedly beamed a message back to the invasion fleet to say they had made it through the Narrows and were into the Sea of Marmara, but no answer was received and AE2 ran on into the night.

Unknown to Stoker, AE2’s message had been heard and news of the submarine’s success conveyed to the top commanders. After the war Stoker was told by Admiral Roger Keys of the morale-boosting effect of the news, as General Sir Ian Hamilton (Commander-in- Chief, Mediterranean Expeditionary Force) had been pondering whether to evacuate the Anzacs. Charles Bean noted in his diary that news of AE2’s breakthrough arrived at headquarters on Gallipoli at about 2.30 a. m. on 26 April 1915. An Australian soldier ashore on that night also said later that the following message was posted at Gallipoli: `Australian sub AE2 just through the Dardanelles. Advance Australia’. It was indeed a great morale booster.

Now the excited Stoker planned to claim a few scalps. From the morning of 26 April and for the next few days, AE2 hunted for Turkish ships in the southern Sea of Marmara. She may not have run amok, but she certainly made her presence felt and deeply rattled the Turks.

AE2 boldly sailed along on the surface, with Turkish fishing boats all around, as Stoker set out to deter Turkish shipping from sailing out south through the Dardanelles with reinforcements for Gallipoli. At one point the cunning Stoker even took AE2 back below the top reaches of the Dardanelles then travelled up through them again with his periscope up, trying to convince the Turks that yet another submarine had broken through the Narrows.

It is a pity Australia’s original fleet of two subs was not still together. AE1 had been lost off New Guinea the previous year.

Just after he tried to create the impression there was another sub with him and just when things were getting too hot, a second Allied boat did arrive. Inspired by Stoker, the British submarine E14, commanded by Lieutenant Commander Edward Boyle, had also got through the gauntlet of the Dardanelles and now joined AE2 to help attack enemy shipping.

Stoker and his men were greatly relieved to see friendly faces:

Five days, about, had passed since we had entered the Dardanelles, vouched for by our experiences, the only true recorders of time’s every varying flight. As one by one the five days had slipped by, the habit of thinking we were alone became so ingrained that realisation of the reverse brought very pleasant surprise.

The two sub captains agreed to run amok together the next day. With double the strength they could really hope to claim some scalps, but next day, 30 April, the torpedo-boat Sultan Hissar, with a gunboat in support, spotted AE2 and forced Stoker to dive as quickly and as deeply as possible.

Then something went wrong and AE2 began to rise uncontrollably, surfacing with its bow sticking out of the water less than 2 kilometres from the torpedo-boat. The submarine had hit swirling patches of denser water that caused it to lose its capacity to stay in balance.

An alarmed Stoker tried to dive again, but AE2 was still out of control and headed well below its maximum permitted depth. There was now the danger it would be crushed by the weight of water, so Stoker ordered full speed astern and blew air into his main ballast tanks. AE2 responded, and this time her stern broke the surface in full view of the Turkish torpedo-boat.

The Sultan Hissar immediately launched a torpedo, which hit and blasted a hole in AE2’s engine room.

Stoker had hoped to use his sub to ram the enemy, but that was now out of the question and he decided to surrender. He ordered his crew on deck immediately, telling them to scramble on board the Sultan Hissar alongside, then scuttled AE2 before the Turks could stop him.

`Within seconds the engine room was hit and holed in three places’, Stoker noted.

Owing to inclination by the bow, it was impossible to see the torpedo boat through the periscope and I considered an attempt to ram would be useless. I therefore blew the main ballast and ordered all hands on deck. Assisted by Lieutenant [Geoffrey] Haggard, I then went round opening all tanks to flood the sub. [Lieutenant John] Cary, on the bridge, watched the rising water to give warning in time for our escape. But then came a shout from him-`Hurry, sir, she’s going down’. As I reached the bridge the water was about two feet from the top of the conning tower.

Stoker got out in the nick of time and, as he boarded the Sultan Hissar, he had the satisfaction of watching his sub sink to the bottom in 55 fathoms. He had done his duty as every captain wished to do on surrendering, cheating the enemy out of taking his vessel as a prize.

The AE2 went down at 10.45 a. m. on 30 April 1915, sliding to the bottom of the Sea of Marmara about 6 kilometres north of Kara Burnu.

Although the Turks herded him and his crew off to a prisoner-of-war camp for the rest of the war-at least none of them had died in this battle.