Ju.87D-8

Unit: Schlachtstaffel 8, ROA

Spring 1945. It was transformed to Nachstchlahtstaffel 2 soon and operated since 13th April 1945.

The Germans transformed its largely psychological role by assigning it tactical bombing duties. Some anti-Soviet airmen of 1. Ostfliegerstafel (russisch) were naturally familiar with the Kukuruznik, and used it no less effectively in the 500 missions they carried out against their fellow countrymen still fighting for Stalin. The irony of these Russians defending northeastern Europe in February 1944 was not lost on other Baltic volunteers who, that same month, formed the 1./NSGr. 12 (lett.).

Its commander-Captain Alfreds Salmins-was Latvian, as were all but 5 of its 124 pilots and support personnel. They operated 18 examples of the Arado Ar. 66c with modified elevators and larger rudder for improved stability in slow flight, and bigger tires for the muddy or rock-strewn flats that were supposed to pass for airfields. The slow, ugly Arado was distinctive for its awkward tail plane configuration, and demanded iron nerves from pilots attempting to score against targets often defended by concerted ground fire. Under cover of darkness as their only real protection, the Latvians flew between unprepared Axis forces and a Red Army buildup going on 30 miles behind the front. Over eight nights of unremitting attacks during mid-May, they delivered more than a thousand 154-pound bombs to the enemy, causing sufficient chaos and casualties, and delaying the Soviet advance long enough for Wehrmacht commanders to ready a successful counterattack.

The Latvians’ timely intervention won fulsome praise from the Germans and a surge of recruits resulting in the formation of another Baltic “Harassment Squadron” The 2./NSGr. 12 (lett.) came into being on June 22, 1944, the third anniversary of Operation Barbarossa. The Axis situation had substantially deteriorated since those early, heady days of irrepressible triumph. Now, immense hordes of Russians and Mongols were poised to descend on the Lithuanian capital. A Soviet steamroller began to move against Vilnius during early July, when all the Baltic Storkampfstafeln engaged in unremitting ground attacks from dusk until dawn, regardless of weather conditions. On the 23rd, 7 of the Second Squadron’s 16 Arados were lost in an unpredicted storm, although all but three pilots eventually found their way back to Gulbene airfield, in northeastern Latvia.

Two days later, men of the 2./NSGr. 12 (lett.) completed their 1,000th mission but were afforded little time for celebration. They were especially busy on August 1, when 35 Arados undertook almost 300 missions in just one night to drop over 50 tons of bombs on Soviet supply concentrations in the vicinity of Jelgava, a city some 30 miles southwest of the Latvian capital. Devastating as these raids were, they could stall but not stop the momentum of a million enemy troops, and the Baltic squadrons withdrew to Salapils airfield, outside Riga. Baltic night-flight operations climaxed after mid-September 1944. Their toll on Soviet forces-especially parked aircraft-relieved pressure on Army Group North, allowing the German command opportunities for effective resistance and civilian evacuation.

By October 8, the two Latvian Harassment Squadrons had completed 5,658 missions over the previous seven months. The bloodied Soviet juggernaut had been slowed, then stopped, but only temporarily. With Stalin’s re-occupation of their homeland, some Estonians lost heart for the fight and defected with their aircraft to Sweden. Although only five Nachtschlachtgruppe pilots dropped out of the war, alarmed Wehrmacht commanders, concerned the trickle of desertions might break out into a flood, disbanded NSGr. 11 (est) over the protests of its more than 1,200 personnel, who affirmed their steadfast loyalty. Both 1. and 2./NSGr. 12 (lett.) were likewise decommissioned, even though no Latvian personnel were guilty of desertion. No less than 80 percent of them had been awarded the Iron Cross and other German and Latvian certificates for valor.

Their flying days were not entirely over, however. A few outstanding airmen were chosen for the creation of two, new Baltic squadrons. The same month that the Night Harassment Groups were disbanded, Latvian pilots of I./JG 54 Grunherz went from the open cockpits of prewar biplanes to the controls of state-of-the-art Focke-Wulf FW. 190A- 8 fighters. Operating first out of Courland, their bases continuously shifted westward into Germany, where they engaged many hundreds of USAAF P-51 Mustangs near Greifswald and over the Eifel Mountains.

Later, the Latvians participated in Operation Boclenplatte, the Luftwaffe’s last hurrah. Its leaders gathered up virtually every surviving aircraft for the Third Reich’s final air offensive on the morning of January 1, 1945, when 1,035 German fighters and bombers struck Anglo-American targets across the Netherlands. Some 300 Allied warplanes were destroyed and at least as many damaged, while enemy airfields were knocked out of commission for the next two weeks. The Luftwaffe lost 280 aircraft, mostly because its new pilots lacked the luxury of time for proper training. One Latvian airman was shot down during the attack. Injured after surviving a forced landing near St. Denis-Westrem, in East Flanders, Lieutenant Arnolds Mencis was set upon and beaten to death by Belgian civilians.

Estonian veterans missed Operation Bodenplatte. They took part in air battles over besieged Berlin during late April and early May 1945, flying FW. 190 fighters to score their final “kills:” From its inception as a flying “police unit” directly responsible to Heinrich Himmler, development into “Harassment Squadrons;’ and final manifestation as the “Night Battle Group 11th Estonian;’ their crews had undertaken more than 7,000 missions on the Eastern Front between February 1942 and October 1944. They contributed importantly to early Axis successes at the Baltic and destroyed enough enemy materiel on the ground through their daring raids in obsolete aircraft to make a difference on the battlefield.

After July 1944, 1. Ostfliegerstafel (russisch) was disbanded, then reorganized as Night Harassment Squadron 8. Its pilots went into action for the first and last time on April 13, 1945, attacking a Red Army bridgehead on the Oder River at Erlenhof, in northern Germany. Their efforts had no effect on the war, which would be over in the next few weeks, but represented instead the Too-Little-Too-Late Problem that undermined Axis hopes for final victory. Long before, the opening guns of Operation Barbarossa had no sooner begun firing, when growing numbers of Red Army Air Force officers and whole crews deserted to the Germans, joining their comrades already taken prisoner, as Luftwaffe volunteers.

They assumed a wide variety of roles, from mechanics and flak gunners to truck drivers and flight instructors. Russian pilots were entrusted with particularly important tasks, such as ferrying aircraft from repair shops behind the lines-and even from Messerschmitt plants inside the Reich itself-directly to waiting Geschwader personnel at the front. By August 1942, so many ex-Soviet airmen had put themselves at the Luftwaffe’s disposal, they formed a unit for the express purpose of creating a new Russian air force aimed at fighting the USSR. Theoretical training began at once, and many Wehrmacht officers became impassioned champions of the proposal. They argued that the Russians proved themselves trustworthy and dutiful. In the hands of these enthusiastic and motivated volunteers, the 1,500 serviceable Red Army aircraft captured by the Germans during the first year of their campaign could help offset the enemy’s terrible numerical advantage. Russian participation on so significant a scale ran against Hitler’s postwar plan to colonize the Ukraine for the permanent relief of Europe’s food crisis and over population. Obtaining this living space would not be possible in the face of justifiable objections made by too many Russians who helped win the war. But all dreams of Lebensraum evaporated in Germany’s steady retreat from crushing defeats at Stalingrad and Kursk, until a confidant of the Fuehrer’s inner circle decided that the Russian volunteers should be mobilized after all.

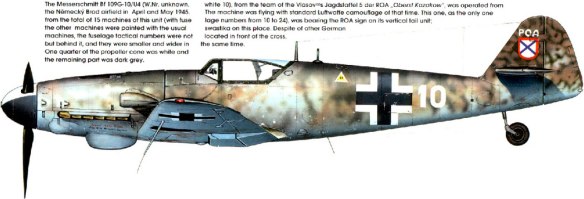

On September 16, 1944, Reichsfuehrer der SS Heinrich Himmler officially recognized the Russkaya osvoboditel’naya armiya, the independent Russian Liberation Army and its National Air Force, which operated separately from but in close cooperation with the Luftwaffe. As some measure of the high esteem in which the Germans held their new ally, select pilots were put through familiarization courses with the top-secret Messerschmitt Me. 262 Sturmvogel for the creation of an all-Russian jet fighter unit. This plan, however, plus months of necessary training, equipping, and organizing, came too late.

At the time of their deployment 17 days before Hitler’s suicide, pilots of Fighter Squadron 5 Kazakov-their Focke Wulf FW. 190s decorated with the ROA insignia of a blue cross in a white disc on a red shield-vainly, if gallantly, opposed Soviet hordes crossing the Oder. What impact they might have had on the course of events in the East, had they been mobilized earlier, remains one of the persistent speculations of World War II. Nor were they the only Eastern Bloc people who served in the German Air Force.

More than 1,000 Galician youngsters volunteered for ground personnel duty with the Luftwaffe. When they turned 18, some transferred to engine mechanics’ school, labor battalions for airfield maintenance, or medical corps. Beginning after New Year’s 1943, Ukrainians with language skills attended translator courses in German, Russian, and English at Prague. They graduated as officers with their own Luftwaffe uniforms, including ceremonial daggers, and a special cuff title emblazoned with their country’s blue-gold national colors and the word, Dolmetsche, for “Translator”.

Eastern Europeans with extraordinary physical and intellectual abilities were eligible for flight training, and some became exceptional pilots in the Luftwaffe. Paul Pianchuk flew 31 combat missions against the Soviets; and Ivan Sushko, together with several other Ukrainian fighter pilots, received the Iron Cross First Class. Serafyma Sytnyk, a former Ukrainian major in the Red Air Force, was the only female pilot in the German Air Force serving at the front.’ Anton Kyivskyj became a wing leader, but the highest-ranking officer of his kind was Major Severyn Saprun, who commanded all Ukrainians in the Luftwaffe. They were distinguished by a blue-gold shield sewn on the shoulder sleeve, signifying the Ukrayins’ke Vyzvol’ne Viys’ko, or Ukrainian Liberation Army, which numbered 80,000 volunteers by war’s end.’

Earlier, many Ukrainians had enlisted in the air arm of the Komitet Oborony Narodov Rossii (“Army for a Free Russia”), created by the former Red Army General Andrei Andreyevich Vlassov, to unite all former Soviet-dominated nations against the USSR, although 20 Ukrainian flight officers signed a petition to Hermann Goering, requesting the formation of a separate all-Ukrainian fighter squadron. The Luftwaffe chief regarded them so highly, he assigned Pavel Olejnyk to command an all-jet unit of Messerschmitt Me-262 Stormbirds for the defense of Berlin, but their operational life was cut short by the close of hostilities in early May.