Go.145

Unit: Erg.NSGr.Ostland

Serial: 6X+LT

The plane was transferred to Erg.NSGr.Ostland (Erganzungs-Nachtschlachtgruppe Ostland = Complementary Night-Attack Group of ROA) from air training school, overpainted unit badge is visible. The machine has silver colour.

Why do we still fly for Germany, even though our homeland is probably lost forever? Because Estonia lives as long as we still fight. Enjoy the war as long as it lasts, because the peace is going to be really horrible! -Karl Lumi, Estonian fighter pilot with 7./JG 4, killed in action April 17, 1945

Of all the Luftwaffe’s foreign allies, none had less auspicious origins than those from which sprouted Estonia’s air force. Despite these humble roots, it eventually blossomed into several Baltic squadrons of over 1,000 men, with more than 200 flight crews highly esteemed by their German comrades-in-arms. Estonia possessed several fighter, bomber, and reconnaissance groups of its own before the Russians arrived in 1940, but these were entirely absorbed by the Red Army after June, and its personnel forcibly entrained for the USSR. Most escaped, fleeing into the countryside, where they formed partisan bands with other patriots of various backgrounds operating against the Soviet invader.

Among these “forest brothers” was Gerhard Buschmann, a member of the Eesti Aeroklubi, a semicivilian flying society controlled by the Estonian Army, who achieved the amazing feat of concealing no less than five aircraft from the Communist occupation authorities. His four PTO-4s were two-seat, low-winged monoplanes, their fixed undercarriages fitted with wheels or skis, plus open or enclosed cockpits, and powered by a 120-hp De Havilland Gypsy engine. Somewhat more substantial was Estonia’s only RWD-8, a rugged, steel-canvas-plywood, two-place high-wing monoplane from Poland, notable for stability and good handling characteristics, but more especially because of its ability to take off and land on rough, unworked fields. With their single, four-cylinder, air cooled, 120-hp PZIn2. Junior engines, RWD-8s were the last Polish machines still flying during October 1939, when, pressed into service as “bombers;’ their crews threw hand grenades at advancing German troops.

Buschmann realized his hidden airplanes could not hope to survive any confrontations with the enemy, and therefore kept them under wraps until real opportunities arose for meaningful resistance. The moment came in early summer 1941, when a German attack swept Stalin’s forces from the Baltic States and Buschmann, like many of his fellow countrymen, joined the anti-Communist crusade. He placed himself, his fellow flying enthusiasts, and their handful of old trainers as a “private squadron;’ an “Estonian unit” at the disposal of their “liberators:” Wehrmacht officers dismissed his proposal with amusement, but Buschmann was not without influence.

A Volksdeutsche, or ethnic German, born in Tallinn, he was a covert pre-war member of German military counterintelligence. Thanks to this Abwehr connection, he was able to confer with the SS Police Commander for Estonia, who was so impressed with possibilities for an indigenous, anti-Soviet air force, he forwarded the notion to his superiors in Berlin. Permission to form the volunteers into their own detachment was soon after received with the proviso that it function as a kind of flying “police unit” responsible only to Heinrich Himmler himself. The Reichsfuhrer believed it would be, if nothing else, at least an important example of “Aryan cooperation against the common enemy: Jewish Bolshevism.”

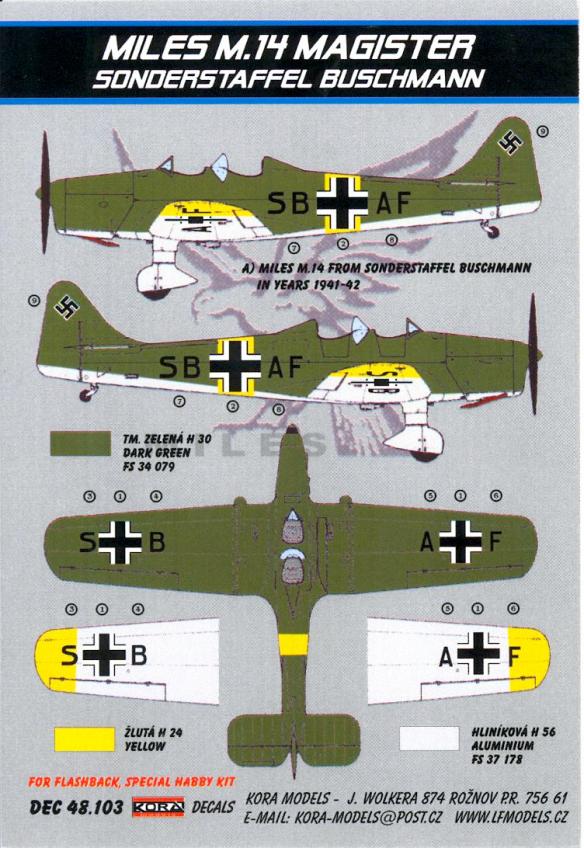

Thus was born Sonderstaffel Buschmann, “Special Squadron Buschmann;’ on February 12, 1942. Wing, fuselage, and tail surfaces of its trainers were repainted with the Iron Cross and swastika, but their propeller hubs bore the blue-black-white national colors of Estonia, and some pilots retained their Estonian uniforms. Others wore civilian dress or German flight suits minus all indications of rank. Before these motley crews could undertake their intended anti-partisan operations, they were essentially commandeered by high-ranking Kriegsmarine officers for the Gulf of Finland, where the German Navy lacked any liaison aircraft of its own. The unarmed Estonian volunteers flew incessant coastal patrols out of Reval-Ulemiste airfield over the next five months, in all kinds of weather conditions, providing invaluable reconnaissance for German shipping.

Their reliability and developing importance impressed Kriegsmarine observers, the quartet of worn-out PTO-4s, and lone RWD-8 were replaced in mid-summer by another Polish trainer in better shape: five Belgian Stampes, one British Miles Magister, and an ex-RAF Dragon Rapicle. The Stampe SV4 was a two-seat trainer, only 35 examples of which were built before the Stampe et Vertongen Company was closed in May 1940. Somewhat more powerful than the Estonians own PTO-4, the SV. 4 possessed a 145-hp Blackburn Cirrus Major III engine marginally better than the inverted, in-line piston De Havilland Gipsy Major I rated at 130 hp that equipped every Miles M. 14 Magister. The spruce and plywood “Maggie;’ as it was popularly known, was an open-cockpit, two-seat, low-wing cantilever monoplane. Another “prize” captured during 1940’s Blitzkrieg was the de Havilland DH. 89 Dragon Rapicle, a short-haul passenger airliner powered by two de Havilland Gipsy Six inline engines rated at 200-hp each.

While these replacements represented some measure of trust the normally parsimonious Germans evidenced for their Baltic allies, they did not constitute much of a real improvement. But the airmen of Sonderstaffel Buschmann were heartily grateful for the relatively “new” machines and carried out their reconnaissance operations with vigor. Meanwhile, their squadron’s namesake was busy rounding up real warplanes for his comrades to be used against Russian submarines prowling the Gulf of Finland in greater numbers. After New Year’s 1943, his tiny eclectic “Special Squadron” had grown to 50 aircraft, mostly cast-off Arado and Heinkel floatplanes, which, although no longer up to frontline service, could more seriously undertake patrols over coastal waters.

The Arado 95 was a single-engine biplane, well liked for its hardihood on rough seas and pleasant handling characteristics in flight, while capable of payloading either 1,102 pounds of bombs or a single 1,764-pound torpedo slung in its own rack under the fuselage. Less beloved was the Heinkel He. 60, made sluggish by a 660-hp BMW VI 6.0 V12 engine and too underpowered to carry anything more than a single 7.92-mm MG 15 machine-gun in a flexible mount for the rear observer. Both types were nevertheless put to vigorous use by their crews, who used Ulemiste Lake for takeoffs and landings.

Their enthusiasm and usefulness had at last come to the notice of Luftwaffe brass, who incorporated the Estonians into the German Air Force. Sonderstaffel Buschmann now became 16./Aufkl. Gr. 127 (See). It immediately lived up to its expectations, directly contributing to the sinking of five enemy submarines trying to break out of the Red Navy base at Kronstadt into the Baltic Sea between May 21 and June 1. Thirteen more Soviet submarines were reportedly destroyed before the unit was withdrawn from its positions. By April 1943, the Reconnaissance Group 127 had attracted so many volunteers, it broke into three squadrons, only one of which continued to perform its duties at sea. The other two formed the Nachtschlachtgruppe 11 (estnisch), the “Night Battle Group 11th Estonian:”

Far more significant than the term implies, Storkampfstafeln, “night harassment squadrons” initiated attacks on enemy positions-often airfields or troop concentrations under cover of darkness or amid conditions of low visibility in slow, obsolete, virtually defenseless aircraft. The attackers would strike just before dawn, at dusk, or during moonlit nights. Sometimes, their arrival was immediately preceded by other aircraft dropping magnesium flares to illuminate the target area. The night harassment fliers depended primarily on surprise for the success of their raids. If caught in the blinding arms of searchlights, they fell as relatively easy prey to ground fire or interceptors. Accordingly, two thirds of the Estonian crews had their floatplanes replaced by no less doddering Heinkel dive-bombers.

Originally designed back in 1931 for the Imperial Japanese Navy, the two-place fabric covered Heinkel He 50 was powered by a 650-hp Bramo 322B radial engine to a miserable top speed of just 146 mph, but it could deliver a 551-pound bomb over 620 miles. Older still were several examples of the Fokker C. V seized after the Germans took Holland. Designed in 1924, it bore every resemblance to a standard World War I-era pursuit airplane fitted with four 110-pound bombs.

A better aircraft provided to Estonian pilots was the Arado Ar. 96, a modern, low-wing monoplane with retractable landing gear. More than 1,150 copies of the Luftwaffe’s standard advanced trainer were produced from 1939 to 1945. But the most common sight in the Storkampfstafeln was the Gotha 145. It equipped all six Axis “harassment squadrons;’ operating in strength until the last day of the war. Altogether, more than 9,500 of the biplane trainers were built for service with the Slovakian, Spanish, and Turkish air forces, as well as the Luftwaffe and Nachtschlachtgruppe. Famous during World War I for the production of large, multiengine bombers, the Gotha Company closed down immediately thereafter, but reopened after Hitler came to power in 1933. Its first new design that year was the Go 145, outstanding for an ability to absorb otherwise crippling punishment and pleasant flight characteristics that made it ideal for covert sorties. Like the Heinkels, Fokkers, and Arados, each Gotha was equipped with a flame-damper over the exhaust manifold to aid in concealment.

Notwithstanding this precaution, after-dark missions undertaken by the crews of these patently outdated aircraft were particularly hazardous for Russia’s changeable weather conditions. Sudden storms or unpredictable cloud cover obscuring the moon could be deadly, and disorientation, even on clear nights, was common. Pilots needed to be highly skilled and just as lucky to survive. But their perilous sorties paid off in handsome dividends, as untold numbers of Soviet warplanes parked in the open were destroyed wherever the NSGr. 11 (est) was stationed. Other victims included trucks, ammunition dumps, fuel storage areas, repair depots, locomotives, railroad stations, and troop concentrations.

Because such operations were conducted at night, the extent of their effectiveness was difficult to ascertain, but it was clearly felt on the battlefield. Success led to the creation of another Storkampfstafel, which came as quite a surprise to the Estonians. In December 1943, the 1. Ostfliegerstafel (russisch) was formed entirely of Russian volunteers. Their duties were identical to those of the other Nachtschlachtgruppen, and they flew the same Arados and Gothas, with a singular addition of the Polikarpov U-2. This was the aircraft that had introduced the very concept of aerial night harassment shortly after the start of Operation Barbarossa.

The rickety Ndhmaschine, or “Sewing Machine;’ as the Germans called it, buzzed their positions in the dead of night, keeping them from their rest and fraying their nerves already worn thin by stressful combat conditions. A U-2 typically came in less than 50 feet above the ground, made a steep climb just before the enemy camp, then leveled off and cut its engine to glide in on the target. All that the sleep-deprived Germans could do was listen to the ghostly whistling of the wind in the biplane’s wire bracing, as prelude to an explosion. After the intruders dropped their bombs, they gunned the engine and sped away, usually with impunity. They caused rare material damage almost entirely by chance, but their impact on the invaders’ mental well-being was significant.

What made such raids all the more vexing was that they were carried out by women. Pilots, even ground crews of the Red Army Air Force’s 588th Night Bomber Regiment, were exclusively female, and cursed by their opponents as Nachthexen. Among the most notorious of these “Night Witches” were Nadya Popova and Katya Ryabova, who successfully completed 18 harassment sorties in just one night. Strangely, the U-2, of 1927 vintage, was virtually impervious to state-of-the-art Luftwaffe fighters or even flak. Cruising at just 68 mph, the little “Sewing Machine” was hard to shoot with a 379-mph Messerschmitt Bf-109G because the target was in and out of firing range within seconds. The Ndhmaschine could also absorb tremendous punishment due to its few vital parts, and its Shvetsov M-11D five-cylinder radial engine was very small.

Moreover, the “Night Witches” flew not only after dark, but at treetop level, rendering interception additionally difficult. Reliable and easy to operate, the Polikarpov U-2 first proved its versatility in agriculture, earning it the nickname Kukuruznik. During the “corn duster’s” military career, it supplied partisans behind the frontlines. In addition to its role as a night-attack aircraft, variants were fitted with sledges or floats, while others could be armed with 265 pounds of bombs and four RS-82 rockets. An air-ambulance version carried a physician, two covered containers for wounded men on stretchers slung under the lower wings, plus provision for two more patients able to sit upright in the fuselage. A later Kukuruznik, the Po-2GN, was known as the “Voice from the Sky” for its powerful loudspeakers that shouted Communist propaganda at Axis troops. With over 40,000 U-2s manufactured between 1929 and 1959, it was the most numerous biplane in aviation history and second only to the more than 43,000 American Cessna 172s as the most mass produced aircraft of all time.