Ferdinand II, Holy Roman Emperor and King of Bohemia

The Battle of Stadtlohn was fought on 6 August 1623 between the armies of Christian of Brunswick and of the Catholic League during the Thirty Years’ War. The League’s forces were led by Johann Tserclaes, Count of Tilly.

Such an army for all its appearance was not in any way comparable to the armies of later years. There was no obvious way of telling one army from another. As any army advanced across the ravaged plains of Germany during the horrors of the Thirty Years War, it was accompanied by bands of irregulars, bandits and marauders, including spies and other n’er-do-wells who plundered the local landscape like locusts.

Armies learnt to distinguish each other by what would in modern parlance be called ‘call signs’. At Breitenfeld in 1631, a battle which threw into sharp relief the energy and skill of the Swedes under their king, Gustavus Adolphus, the Imperialists under Tilly shouted ‘Jesus-Maria’ as they fought while the Swedes used the phrase: ‘God with us’. As battles were fought and won, it became the custom to reward the officers and men with financial gifts. Thus after Lutzen, General Breuner was given 10,000 gulden while the brave Colloredo regiment was awarded collectively 9,200 gulden.

The names of the Imperial officers came from two sources. The aristocrats who had preferred to convert to Catholicism took full advantage of the political support Ferdinand offered them. Many of the names we encounter here for the first time will pop up again and again in our story: Khevenhueller, Trauttmannsdorff, Liechtenstein, Forgách, Eggenberg and Althan (these last two left behind them world-class works of architecture to commemorate their position and wealth: Schloss Eggenberg, on the outskirts of Graz, and Vranov – Schloss Frein – in Moravia). Then came a group whose careers were made in the long Turkish wars. These included not only Ferdinand’s enemies Thurn, Hohenlohe, Schlick and Mansfeld, but a large number of his most important military commanders from Wallenstein downwards.

By 1620, Ferdinand was ready to move on to the attack. He now had no fewer than five separate armies with which to renew the offensive. Dampierre held Vienna with 5,000 men. Bucquoy was advancing along the Wachau with 21,000; from Upper Austria, the Duke of Bavaria, Maximilian, advanced alongside Tilly with 21,000, while a Spanish army invaded the Lower Palatinate. The previously Protestant lands of Lower Austria and Upper Austria were cleared of the rebels and more than sixty Protestant noblemen fled to Retz with their families. Half of these would be proclaimed outlaws. Both provinces had been recovered for Ferdinand and the Church with barely a shot being fired.

As the armies advanced into Lusatia and Moravia, the irregular forces of the Emperor began to introduce a far more brutal and indiscriminate warfare. Plundering, rape and other atrocities became widespread, especially among the Cossacks sent by the Polish Queen who was Ferdinand’s sister. On the rebels’ side Hungarian irregulars proved no less capable of atrocities and had in Ferdinand’s own words ‘subjected the prisoners to unheard of torture …’ killing pregnant women and throwing babies on to fires. Ferdinand would later note: ‘So badly have the enemy behaved that one cannot recall whether such terror was the prerogative of the Turk.’

These acts of cruelty set the tone for much of what occurred later. On 7 November 1620 Maximilian and Tilly finally reached the outskirts of Prague where they faced the new rebel commander, Prince Christian of Anhalt, who had taken up a potentially strong defensive position exploiting the advantage of the so-called White Mountain, in reality more of a hill, a few miles to the west of Prague.

Anhalt’s forces consisted of about 20,000 men of whom half were cavalry. Some 5,000 of these were Hungarian light cavalry. His artillery consisted of only a few guns. The entrenching tools to convert his position into something more formidable never arrived. Thus was the stage set for destruction of the Bohemian rebels. The Imperial forces were superior in artillery, but more importantly in morale. The commanders were divided on what they should do next and it was only when an image of the Madonna whose eyes had been burnt out by Calvinist iconoclasts was brandished in front of Wallenstein’s ally Bucquoy that he suddenly ordered the attack.

Anhalt deployed his cavalry but they made no impact on the Imperial horsemen and they fled after an initial skirmish. The Bohemian foot followed rapidly and even the feared Moravian infantry dissolved when Tilly appeared in front of them. The Battle of the White Mountain was over by early afternoon. The Imperial forces had suffered barely 600 casualties and the rebels more than 2,000 but what turned this skirmish into a decisive victory was Tilly’s determination to keep up the momentum against a demoralised enemy. Prague, despite its fortifications, surrendered as rebel morale everywhere collapsed. Frederick joined the fugitives streaming out of the city to the east, leaving his crown behind him along with the hopes of a Protestant Europe. As the Czech historian Josef Pekař rightly observed, the Battle of the White Mountain was the clash between the German and Roman worlds and the Roman world won. Had the German world won, Bohemia would have rapidly been absorbed by Protestant Germany and Czech culture would have ceased to exist.

For Protestantism, with the departure of the Winter King and his wife into exile in Holland, the tide of history which had seemed to run in the direction of the new faith in the sixteenth century now appeared to have turned irrevocably. Increasingly perceived as divisive, unhistorical and radical, Protestantism unsettled those who feared anarchy and extremism. The population of Prague sought refuge in the old certainties and comfortable verities of the Catholic Church and within a year the Jesuits had made the city into a bulwark of the Counter-Reformation.

As Professor R.J.W. Evans has pointed out, the demoralised forces of the new faith had little reply to the intellectual and practical solutions of the Society of Jesus. Those who sought refuge in the occult and Rosicrucian view of the world were ‘qualified at best only for passive resistance to the attacks of the Counter-Reformation’.

Moreover not only did Ferdinand’s personal piety inspire his subjects through the widespread dissemination of the Virtutes Ferdinandi II penned by his Jesuit confessor Lamormaini, but the international flavour of the new orders, like Ferdinand’s army, was a powerful intellectual weapon. At the opening of the Jesuit University of Graz the inaugural addresses had been given in eighteen languages. When Ignatius Loyola had founded the Society of Jesus in 1540 he had from the beginning conceived it as a ‘military’ formation led by a ‘general’ who expected unhesitating obedience and the highest intellectual and spiritual formation among his recruits. These principles guided Ferdinand’s vision of his army. The offensive of the intellect was supported by more practical steps. In 1621, all of the ringleaders of the Bohemian rebels were executed on Ferdinand’s orders in the Old Town Square in Prague.

It was typical of Ferdinand II that while these ‘Bohemian martyrs’ were brought to the gallows, the Habsburg went on a pilgrimage to the great Marian shrine of Mariazell in his native Styria specifically to pray for their souls. In the years that followed, prayer and sword moved in perfect counterpoint for the Habsburg cause. If Ferdinand was the spearhead of spiritual revival, on the battlefield the corresponding military reawakening was to be organised by Wallenstein.

Wallenstein stood out from the newly minted nobility around Ferdinand because of his logistical skills, which he deployed with unrivalled expertise despite his physical disabilities. Plagued by gout which often forced him to be carried by litter, Wallenstein ceaselessly instructed his subordinates to organise his affairs to the last detail. Agriculture was virtually collectivised under his control to ensure that every crop and animal was nurtured efficiently to supply his armies. A fortunate second marriage to the daughter of Count Harrach, one of Ferdinand’s principal advisers, brought him yet more support at court. In April 1625, Ferdinand agreed to Wallenstein raising 6,000 horsemen and nearly 20,000 foot soldiers. Wallenstein’s force gave the Emperor freedom of manoeuvre. He now had formidable forces to counterbalance the armies of the Catholic League led by Tilly, who always showed signs of answering in the first instance to his Bavarian masters rather than to the Emperor Ferdinand.

Imperial pikemen, Thirty Years War

Wallenstein’s ‘system‘

At Aschersleben, Wallenstein created a depot for some 16,000 troops. More would follow. By 1628 the Imperial armies would number 110,000, of whom a fifth would be cavalry. From 1628, Wallenstein’s prestige grew and he was given control of all forces in the Empire with the exception of those in the crown lands and Hungary. Many foreign soldiers of fortune, including English, Irish and Scottish officers and even well-known German Protestants such as Arnim, joined Wallenstein as the Imperial army rapidly expanded. Despite the religious feuds of his era, the ‘Generalissimus’ was indifferent to the faith of his commanders. What he valued above all was loyalty and ability.

Wallenstein is largely credited with mastering the logistics of war on a scale hitherto not achieved. By forcing officers to be responsible for the upkeep and pay of their men, Wallenstein obliged villages and towns to contribute to war, thus allowing the impoverished Ferdinand to wage war without regard to the sorry state of his treasury. By levying contributions from enemy states his forces occupied, Wallenstein systematised plunder. In addition, thanks to his own vast resources, he constructed an elaborate system of loans and financing to assist his hand-picked officers with their quotas and his senior commanders with their expenses. By 1628 a colonel in one of Wallenstein’s regiments was receiving 500 florins (approx. $500) a week, more than an officer in other armies received in a month. The normal pay for a foot soldier was at this time barely 8 florins a month.

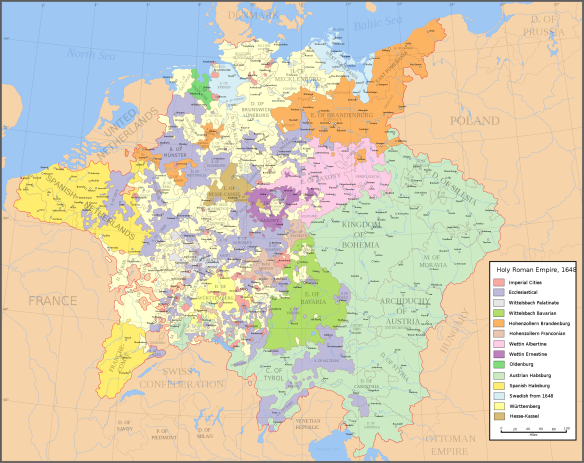

The imposition on the local population defied both convention and even Imperial law. According to this soldiers could demand lodging but were expected to pay for food. In practice this was impossible, owing to the scale of Wallenstein’s forces and their vast cohort of camp-followers. The villages and unfortified towns were ruined, with those houses refusing to pay levies often being torched. More funds could be acquired by ‘tributes’ from wealthy parts of the country, which could be exempted from supplying troops or occupation in return for large payments. Many of these sums were significant; for example Nuremberg paid half a million florins. But the cost, however great, was considered preferable to the destruction that accompanied occupation. Large swathes of Germany thus existed in a state of near-perpetual extortion in which Imperial decrees and laws appeared utterly overtaken by the rules of war. From Saxony to Brandenburg and Pomerania, from Mecklenburg to Württemberg expropriation became the order of the day. Elsewhere, in the crown lands, the ‘Soldier Tax’ became a weekly feature of urban life.

This ‘system’, such as it was, could be open to abuse. At a time of mercenary recruitment the commercial possibilities of all these activities were not lost along the many links of the chain. Bribes, ‘Spanish’ practices such as drawing supplies for non-existent soldiers, flourished in an era where the drawing up of accounts left much to be desired. Nor were these crimes the exclusive prerogative of any one army. For the populace of Germany, the Thirty Years War was truly a terrible era.

Elsewhere in the Habsburg domains taxation was used to preserve the great armouries in the cities of Inner Austria and maintain the Military Frontier which had developed in the late 1570s into a ragged line of frontier posts stretching some fifty miles alongside the Ottoman frontier. This was extended to include the approaches to Graz along the Drave around Varaždin and the area around Karlstadt (Karlovac) in Croatia proper as well as the three sections of the Hungarian frontier. Central funds from the Reichstag covered the costs of the principal garrisons (1.2 million florins a year) but elsewhere families were encouraged to take on the responsibility of particular areas of land, leading eventually to the creation of a warlike caste of military families with their own laws, customs and indeed dialect (Militärgrenze-Deutsch, for example ‘Ist Gefällig’ for ‘Izvolite’, which was heard around Koprivnica in eastern Croatia/Slavonia up to the mid-1970s).

That Wallenstein’s ‘system’ was capable of functioning at all was the result of his bankers, notably Jan de Witte who deploying an extensive network raised money for Wallenstein in sixty-seven cities between London and Constantinople. The powerful financiers of the time, de Witte and Fugger, would lend to Wallenstein when they would never lend to a Habsburg, their fingers having been burnt too often in the past by Ferdinand’s family’s hopelessness with money. But the financial architecture these resourceful and able men now constructed was only possible through generous interest rates and as their financing system came more and more to resemble a giant pyramid scheme it could be sustained only by the sale of vast estates enabled by royal prerogative. Ferdinand dealt with Wallenstein’s bills the only way he could – by ceding yet more land to the warlord.

Imperial musketeer and caliverman of the Thirty Years’ War.

The strategic tide was flowing in Ferdinand’s direction. Everywhere the anti-Habsburg coalition was faltering. As the 1620s wore on, Tilly dealt with the Danes at Lutter where in 1626 for 700 casualties he routed an army under Prince Christian, inflicting thousands of dead, wounded and captured. At one point the battle appeared to be turning in the Danes’ favour but the dispatch of 700 of Wallenstein’s heavy cavalry turned the tables with dramatic effect.

Wallenstein meanwhile had negotiated a truce with the Hungarian rebel leader Gabor Bethlen, a zealous Calvinist who claimed to have read the Bible twenty-five times and who had led an anti-Habsburg insurrection one of whose victims indeed had been the cavalry officer Dampierre. But though the Hungarian Protestants harboured many grievances against the Habsburgs, without external support there was little they could hope to achieve.

At the same time the Danes had retreated, leaving Saxony and Silesia to Wallenstein’s mercy. In May 1627 Wallenstein received the Duchy of Sagan instead of 150,850 florins owed to him by the Emperor, who now continued to write off any further debts to Wallenstein through granting him land. Titles fell to Wallenstein as rapidly as his opponents on the battlefield. He was elevated to Reichsfurst (with its concomitant right of access to the Emperor) and enfeoffed as a duke (Mecklenburg). Even his own coinage began to circulate, to the irritation of the court in Vienna.