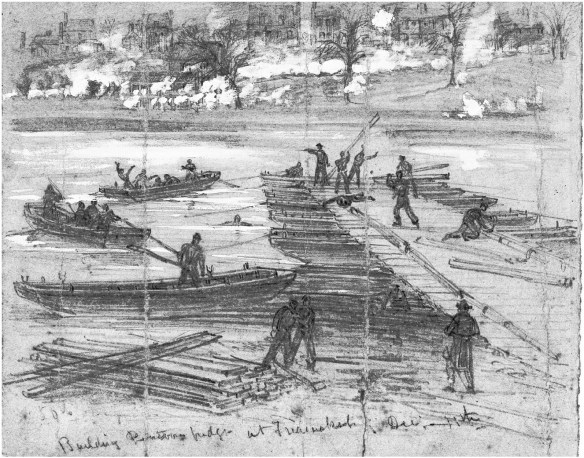

Alfred Waud sketched the 50th New York Engineers, supported by artillery, assembling a pontoon bridge across the Rappahannock at Fredericksburg on December 11.

To act on Burnside’s call for a second bridge train, Woodbury had pontoons “rafted” for towing down the Potomac by steamer. He optimistically expected that the wagons and teams that had delivered the land train would transport these second-train pontoons to Falmouth. The pontoons arrived on November 18, but no wagons and teams were waiting. Delay upon delay had dogged the land train; it did not even leave Washington until the 19th.

To try and make the second train operational, Woodbury extemporized, loading the needed pontoon wagons aboard barges for the journey down the Potomac, only to be held up by a winter storm. The land train was bogged down by interminable rain. Stalled at the Occoquan River, unable to reach either Falmouth or Aquia by road, the desperate engineers rafted the pontoons, disassembled the wagons, and loaded them aboard for towing by a steamer, with the teams going on by road. At last, after vast effort and great difficulties, the two trains were landed, assembled, and reached Falmouth . . . on November 24–25.

Without the initial six-day delay, with initiative and planning in Washington, or with the army’s march held up as Woodbury suggested and Halleck rejected, one or both bridge trains ought to have arrived at Falmouth in concert with the army. Deceitful Halleck denied everything, even that Woodbury had come to him about delaying the march. As it was, Burnside and the Army of the Potomac hunkered down at Falmouth and watched a full week’s worth of opportunity slip away while waiting for the pontoons. Across the Rappahannock, at Fredericksburg, the Army of Northern Virginia assembled in force.

In notable contrast to McClellan, the new commanding general accommodated advice, proposals, and plans from his officer corps. General Burnside, said Chief of Staff Parke, “would not think of making an important movement of this army without full consultation with his generals.” Bull Sumner, finding Fredericksburg empty of Confederates on reaching Falmouth November 17, proposed to Burnside that he cross a force at a nearby ford and seize the town. He was told it was best they first secure their communications. Sumner could appreciate that; he remembered only too well the consequences at Seven Pines “of getting astride of a river. . . .”

Joe Hooker came up with a plan of more ambition, which he submitted to Burnside on November 19 (sending a copy to his prospective patron, Secretary Stanton). With his Center Grand Division, Fighting Joe proposed to cross the Rappahannock well upstream at U.S. Ford and swing south and east to plant his 40,000 men on the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac at Hanover Junction, south of Fredericksburg. He would draw his supplies from a new depot at Port Royal, well downstream on the Rappahannock. His move should catch the Rebels off-guard, for they “have counted on the McClellan delays for a long while.” In any case he was strong enough to cope with any Rebels his move might stir up. Hooker’s stated objective would have warmed Mr. Lincoln’s heart: “If Jackson was at Chester Gap on Friday last, we ought to be able to reach Richmond in advance of the concentration of the enemy’s forces.”

Burnside replied that Hooker’s proposal “would be a very brilliant one” and would possibly succeed, but he thought it “a little premature.” It was 36 miles to the R. F. & P. via U.S. Ford; with the heavy rains of the past two days there was a question of the ford’s viability; the uncertainty of the pontoons’ arrival made support for Hooker’s column problematical. (Boldness, it seemed, was as lacking in Burnside as in McClellan.) To Secretary Stanton on December 4 Hooker grumbled that if Burnside had approved crossing the Rappahannock when they had the chance, they would not now be suffering “the embarrassments arising from the passage of that river, the greatest obstacle between this and Richmond.”

Burnside learned on November 19, the day he reached Falmouth, that his bridge train was only that day leaving Washington, strong evidence his plan to cross at Fredericksburg was in jeopardy. Nevertheless, he rejected Hooker’s idea for a crossing upstream, and made no effort to investigate a downstream crossing either. He stubbornly stayed where he was, waiting (as McClellan would say) for something to turn up—in this case, pontoons.

The days passed and Burnside progressed from uneasy to frustrated to baffled as to what to do. Sumner had called on Fredericksburg’s mayor to surrender the town: “Women & children, the aged & infirm” should evacuate. The negotiations revealed that Longstreet’s corps was coming on the scene. Marsena Patrick noted in his diary, “Burnside feels very blue. Lee & the whole Secesh Army are, or will be, in our front.” Burnside made only mild complaint to Halleck about the nonarrival of the pontoons, but Daniel Larned of his staff affixed the blame directly: “Had the authorities at Washington executed their part of the plan with one half the promptness and faithfulness that Burnside has done his, our command would have occupied the City of Fredericksburg three days ago. . . . We are utterly helpless until our pontoon trains arrive.”

On November 22 General Sumner dined with Generals Hooker, Meagher, and Pleasonton, wherein “all agree our march to Richmond will be contested inch by inch.” This inspired Sumner to again offer his thoughts to the general commanding. With the enemy now present in force across the river, he cautioned that throwing bridges “directly over to the town, might be attended with great loss” from artillery and from “every house within musket range. . . .” He proposed instead establishing a “grand battery” of thirty or more heavy guns a mile or so downstream, where the far shore was an open plain, “which would effectually sweep off every thing for a long distance.” The navy might add gunboats to the barrage. Against this fire the enemy would be unable to throw up works to prevent the bridge building. Sumner observed that the Rebels’ position on the high ground behind the town looked very strong. But cross below, form the whole force in line of battle, “then by a determined march, turn their right flank, is it not probable that we should force them from the field?” Burnside took note for further consideration.

“We in this Army think this whole campaign is a gross military mistake,” force-fed by Radical politicians in Washington, wrote William Franklin; the true road to Richmond, he told his wife, “is by a more Southern route with less land travel.” John Gibbon agreed, and submitted such a plan to headquarters—hold a bluff at Fredericksburg, where the chance for a surprise crossing had passed, take a new base at Suffolk, and operate up the James River to seize the railroad hub of Petersburg. “Once in possession of Petersburg, Richmond will fall.” Burnside recognized Gibbon’s plan as too McClellanesque for the occasion.

Mr. Lincoln was monitoring his new general and became concerned enough that he signaled him they should meet at Aquia Landing for consultation. They met aboard the steamer Baltimore on November 27. The president made a memorandum of the conversation: Burnside said he could take to battle about 110,000 men, as many as he could handle “to advantage.” Their spirits were good. He was committed to crossing the Rappahannock—he offered nothing specific about that—and driving the enemy away, but admitted it would be “somewhat risky.”

“I wish the case to stand more favorable than this in two respects,” Lincoln wrote. First, he wanted the river crossing “nearly free from risk.” Second, he did not want the enemy falling back unimpeded to Richmond’s defenses. He proposed a plan of his own. While Burnside paused where he was, a 25,000-man force would take post on the south bank of the Rappahannock downstream at Port Royal to divert Fredericksburg’s defenders. A second 25,000-man force, escorted by gunboats, would ascend the York and Pamunkey rivers to near Hanover Junction on the R. F. & P. (Hooker’s target, reached by the back door) to block the Rebels’ escape route. “Then, if Gen. B. succeeds in driving the enemy from Fredericksburg, he the enemy no longer has the road to Richmond.”

On November 29 Burnside journeyed to Washington to discuss this new plan with the president and Halleck. Neither general favored it, and Lincoln added a note to his memorandum: “The above plan, proposed by me, was rejected by Gen. Halleck & Gen. Burnside, on the ground that we could not raise and put in position, the Pamunkey force without too much waste of time.” Turning aside Lincoln’s idea, gaining no counsel from Halleck, Burnside returned to Falmouth no wiser about what he should do.

His thoughts finally turned to a downriver crossing, at a bend called Skinker’s Neck a dozen miles from Falmouth. He briefed his generals on December 3 and scheduled the march for the 5th. Irreverent Hooker spoke up that he would like to be on the other shore with 50,000 men and dare anyone to cross. Skinker’s Neck was in fact an idea with promise . . . if attempted ten days earlier upon the arrival of the first bridge train. Now Stonewall Jackson’s corps was occupying the downstream river line. The march was well started when word came that Skinker’s Neck was heavily guarded. The marchers turned back to camp.

Originally Ambrose Burnside had sought, by speed or by maneuver, a new road to Richmond, flushing the enemy into the open. But through miscue and misadventure and mismanagement that opportunity was gone. The Army of Northern Virginia was directly across the river, entrenching as he watched. Afterward Burnside testified to his rationale for fighting at Fredericksburg: “I felt we had better cross here; that we would have a more decisive engagement here, and that if we succeeded in defeating the enemy here, we could break up the whole of their army here, which I think is now the most desirable thing, not even second to the taking of Richmond.” Beforehand he assured Baldy Smith he would make the crossing “so promptly that he should surprise Lee, that he knew where Lee’s troops were, and that the heart of the movement consisted in the surprise.”

At noon on Tuesday, December 9, Burnside called in Sumner, Hooker, and Franklin, his three grand division commanders, and outlined the plan he had settled on. Sumner announced to his staff “the determination to cross the Rappahannock with the Army at daybreak Thursday morning. . . .” Sumner’s Right Grand Division would have the advance, crossing on three pontoon bridges to be laid directly opposite Fredericksburg “under at least 150 cannon on our shore.” Hooker then to cross as a reserve. Crossing “a mile or two below on 2 bridges” would be Franklin’s Left Grand Division. To Washington Burnside staked his claim: “I think now that the enemy will be more surprised by a crossing immediately in our front than in any other part of the river.” His three senior commanders, he said, “coincide with me in this opinion.”

What Sumner had warned Burnside would happen, happened—sharpshooters filled Fredericksburg’s riverfront buildings and their fire riddled the engineer teams and drove them back, leaving the three bridges unfinished about midstream. The artillery Burnside counted on to clear the way pounded the opposite shore, but each time the engineers returned to work the sharpshooters returned to their postings and chased them back. Franklin proposed that he cross the lower bridges and flank the sharpshooters. Burnside rejected that as too risky, insisting on establishing the bridgeheads simultaneously. He demanded the engineers complete the bridges “whatever the cost.”

Major Ira Spaulding of the engineers, who had displayed great initiative in getting his bridge train through hell and high water to Falmouth, proposed a solution to the dilemma—row infantry across in pontoon boats to scour the sharpshooters out of their hiding places. The idea got to General Hunt, who with Burnside’s approval sought volunteers. In Colonel Norman J. Hall’s brigade, Hall volunteered the 7th Michigan, the regiment he had led to war, to cross at the upper bridges. Colonel Harrison S. Fairchild’s 89th New York was tapped to cross at the middle bridge. Hunt laid on the heaviest shelling yet, driving the sharpshooters to cover, and the little fleet was poled and paddled with all speed across the river. There were casualties, but the two regiments made landings on the enemy shore. Support followed. Watchers on the Yankee shore went “wild with excitement, cheering and yelling like Comanche Indians.”

In house-to-house fighting the Confederates were driven away and the engineers completed the three Fredericksburg bridges, but the hour was late. Otis Howard’s Second Corps division crossed and by dark had secured the bridgehead. Charles Devens’s brigade, Sixth Corps, secured the lower bridges site. It had been a long and difficult day, especially for the engineers, but Burnside accepted it as a ponderous first step in a deliberate challenge to Lee. “I expect to cross the rest of my command tomorrow,” Burnside told Halleck.

Early on December 12 Burnside endorsed a Franklin dispatch, “As soon as he and Sumner are over, attack simultaneously.” Nothing came of this spare directive, for it required the entire day to get the army across the river and into position to advance . . . the next day. General Lee watched, detected no Yankee deceptions, and called in Stonewall Jackson from his downriver postings. The entire Army of Northern Virginia was at hand, ready for whatever General Burnside might attempt. These latest of the many delays ended Burnside’s last hope for catching the Rebels unwary or out of position. The crossing, John Reynolds contended, “ought to have been a surprise, and we should have advanced at once and carried the heights as was intended.”

On the low ridge called Marye’s Heights behind Fredericksburg Longstreet had spent three weeks entrenching and posting batteries. At the base of the ridge he had infantry thickly ranked along the Telegraph Road behind a chest-high stone wall—analogous to the Sunken Road at Antietam. Marye’s Heights ended at Hazel Run; from there Jackson took post on low wooded hills extending to Hamilton’s Crossing on the R. F. & P. Massaponax Creek marked the end of a battle line six miles long.

Burnside’s orders set Sumner’s objective on the right as “the heights that command the Plank road and the Telegraph road,” that is, Marye’s Heights. Franklin on the left was to “move down the old Richmond road, in the direction of the railroad,” referring to the Richmond Stage Road from Fredericksburg that paralleled the river and the R. F. & P. Hooker’s Center Grand Division would stand ready to support either Sumner or Franklin as need be. Nothing was said of timing, of priorities, or in Franklin’s case, of objective. Unlike his predecessor, Ambrose Burnside was not haunted by the underdog’s role. While he testified to receiving estimates of enemy numbers as high as 200,000, he made his own estimate—less than 100,000. (Lee’s actual count was about 78,500.)

Sumner’s command—Second and Ninth Corps—had required December 12 to crowd across the three bridges into Fredericksburg. The shelling on the 11th had chased away the last few residents and the town was empty. The troops stood idle, stacking arms and wandering the streets. When Provost Marshal Marsena Patrick reached the scene, “a horrible sight presented itself. All the buildings more or less battered with shells, roofs & walls all full of holes & the churches with their broken windows & shattered walls looking desolate enough.” But that was not the worst of it: “The Soldierly were sacking the town! Every house and Store was being gutted!”

Few restraints had marked the Potomac army’s passage through Virginia since late October. No restraints marked it now. The sack began with a search for food in the abandoned dwellings, then wine cellars and liquor stocks were raided, fueling a rising tide of plunder and vandalism. Fredericksburg’s colonial heritage was ransacked and its artifacts, from carpets to libraries to paintings to spinets, defaced or thrown into the streets. Powerless to restore order, Patrick posted the bridges to at least stop looters from stealing away with their booty. Officers of every rank looked the other way. “Never was a city more thoroughly sacked,” wrote a shocked New Hampshire colonel. “The conduct of our men and officers too is atrocious their object seems to be to destroy what they cant steal & to steal all they can.” In the annals of the Army of the Potomac it was the ugliest of days; for its officer corps, the most unconscionable of days.

While their troops crossed at the lower bridges—christened Franklin’s Crossing—Franklin and John Reynolds (First Corps) and Baldy Smith (Sixth Corps) discussed their next move. Absent fresh orders from headquarters, they agreed, said Smith, that the Left Grand Division should form its 40,000 men “into columns of assault on the right and left of the Richmond road,” carry Hamilton’s Crossing on the railroad, “and turn Lee’s right flank at any cost.”

At early evening on the 12th Burnside arrived at Franklin’s headquarters to inspect the position and to settle on a plan for the next day. By the accounts of Franklin and Smith, Burnside was attentive and responsive to their proposed plan of attack. Franklin termed it “a long consultation.” Smith had Burnside responding, “Yes! Yes!” to their objective—“turn Lee’s right flank at any cost.” This matched Sumner’s November 23 plan that Burnside had already adopted regarding the Franklin’s Crossing site—after crossing, “by a determined march, turn their right flank.” It seems clear that Sumner’s forceful plan was already on Burnside’s mind when he heard more or less the same plan from Franklin, Smith, and Reynolds. To be sure, theirs did not include the “whole force” as Sumner’s did. Yet Franklin’s two full army corps, six divisions, surely counted enough for the task at hand. Burnside promised two of Hooker’s divisions to hold the bridges when Franklin’s flanking attack commenced—raising Franklin’s total to some 60,000 men—and to send written orders for the morrow.

In consequence of those orders, received at 7:30 the next morning, Franklin afterward raised an elaborate construct to defend his conduct when he went to battle on December 13. This construct revealed striking echoes of his last exercise of independent command, at Crampton’s Gap on South Mountain in September, where he misjudged his assignment, shunned both initiative and responsibility, and in his caution quite misread the battlefield.

Ambrose Burnside was strained and wanting sleep, and his orders were poorly framed and hardly a model of clarity. Still, that fails to account for the contrary interpretation Franklin put on them. If at their December 12 council Franklin and his generals came to a firm agreement (as they claimed) with Burnside about a full-blooded assault to turn Lee’s right, then Burnside’s December 13 orders, however awkward the phrasing, took as a given a fully discussed, already-agreed-upon plan.

“The general commanding,” the orders read, “directs that you keep your whole command in position for a rapid movement down the old Richmond road, and you will send out at once a division at least . . . to seize, if possible, the height near Captain Hamilton’s”—Prospect Hill, overlooking Hamilton’s Crossing—“taking care to keep it well supported. . . .” Seizing Prospect Hill was necessary to open the way for the Left Grand Division to drive between Hamilton’s Crossing and the Massaponax and into Lee’s rear. Burnside’s orders twice spoke of Franklin employing his “whole command” for the operation. Sumner would meanwhile assault the other end of the Confederate line, Marye’s Heights, thereby compelling “the enemy to evacuate the whole ridge” . . . or so Burnside hoped.

Before the Committee on the Conduct of the War, Franklin testified to his entirely different reading of the December 13 orders: “It meant that there should be what is termed an armed reconnaissance, or an observation in force made of the enemy’s lines, with one division. . . . At that time I had no idea that it was the main attack.” This tortured reading, this convenient forgetting what had been discussed and agreed to at the generals’ council the previous evening, starkly reveals (once again) William Franklin’s incapacity for independent command. He had a telegraphic link with headquarters to clarify his orders if they were “not what we expected.” He did not use it. Nor did he take the lead in posting his forces for prompt action on the 13th. Nor did he pay even lip service to gainfully employing his “whole command.” He confined the Sixth Corps to keeping open a line of retreat and guarding Franklin’s Crossing, even though he had two Third Corps divisions for just that purpose. He assigned the “armed reconnaissance” to John Reynolds.

In the controversy over Franklin’s reading of his orders, Burnside made the incisive point: Surely Franklin realized “I did not cross more than 100,000 over the river to make a reconnaissance.” Writing his wife, Franklin revealed an untrustworthy state of mind on December 13: “It was not successful and I never thought it would be, but I knew that it had to be made to satisfy the Republicans, and we all went at it as well as though it was all right.”

Sumner, good soldier that he was, may have coincided, but certainly with mixed feelings. Burnside had adopted Sumner’s November 23 suggestion for a bridging site a mile or so downstream where the enemy shore was open and vulnerable, but in the same breath he ignored Sumner’s very pointed advisory against throwing bridges across right at Fredericksburg’s well-defended riverfront. Hooker for the moment held his tongue, his grand division having only a follow-up role in the crossing. Franklin too coincided, recognizing that he had the less risky crossing site of the two.

There was no such unanimity among the Right Grand Division generals that evening when Sumner briefed them. Darius Couch wrote that no words were minced: “The general expression was against the plan of crossing the River.” Poor Sumner defended a plan out of loyalty to the commanding general that privately he deplored. Word of the dissenters got back to Burnside, and the next evening he minced no words of his own to the generals gathered at Sumner’s headquarters. Otis Howard quoted him, “Your duty is not to throw cold water, but to aid me loyally with advice and hearty service.” Couch said Burnside “plainly intimated that his subordinates had no right to express any opinion as to his movements.” Burnside took issue with Winfield Hancock’s plaints. Hancock replied that while he had meant no personal discourtesy, it was certain to be “pretty difficult” to contend against an entrenched foe at their crossing site. Still, Hancock pledged his loyal support, as did Couch in defending his division commander. Amidst these professions of fealty, bluff William French joined the gathering and asked, “Is this a Methodist camp-meeting?”15

At an early hour on December 11—day 24 since Sumner arrived at Falmouth and found no bridge train waiting—the engineers hauled pontoons and gear to the riverbank and by first light were well started assembling their bridges. Henry Hunt posted 147 guns for support. Initially fog blanketed the river, and the engineers could be heard but not seen as they labored to anchor their pontoons, link them with timber balks, and lay down planking. Downstream the two lower bridges met only sporadic enemy fire, quickly suppressed, and by 11:00 a.m. both were completed. But Franklin was told to hold up his infantry. The middle bridge crossing, at the lower end of Fredericksburg, and the upper, two-bridge crossing at the upper end of town, progressed only as long as the fog lasted. The Rappahannock here was hardly 140 yards across, and as one of the engineers put it, “For us to attempt to lay a Ponton Bridge right in their very faces seemed like madness.” As the fog lifted the madness turned into “simple murder, that was all.”