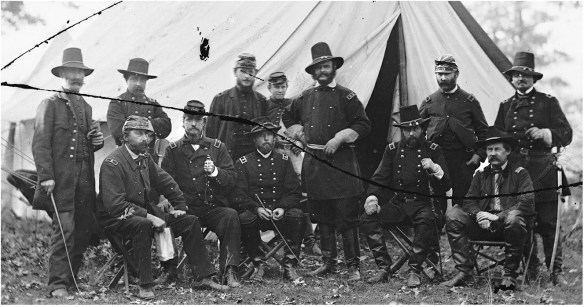

Burnside with a bevy of his generals, photographed by Alexander Gardner on November 10, 1862. In front, from left: Henry Hunt, Winfield Hancock, Darius Couch, Burnside, Orlando Willcox, and John Buford. At rear, from left: Marsena Patrick, Edward Ferrero, John Parke, a staff man, John Cochrane, and Samuel Sturgis.

Pontoon bridges placed by Union forces across the Rappahannock River at Fredericksburg in December 1862. Photo from National Park Service, Fredericksburg and Spotsylvania National Military Park Photo Gallery, online at http://www.nps.gov/frsp/photosmultimedia/photogallery.htm.

That twice before he pressed the Potomac army command on Burnside (reports of which had leaked out) had tempered Lincoln’s choices for a new commanding general. In any case, Burnside had certain qualities that at this critical moment in the army’s history commended him to the post. He did well enough on the North Carolina coast and at South Mountain. At Antietam he performed no worse than several other Federal generals. He was an outsider yet not a stranger to the officer corps. He was considered a friend of McClellan’s yet did not owe his place to him. Although he fought at First Bull Run and lately in Maryland, he was not so deeply rooted in the Army of the Potomac’s culture and politics that his independence was compromised. Just that reason drew Lincoln to Burnside in the first place—he seemed apolitical.

Joe Hooker had the better fighting record, certainly, but Hooker’s outspoken faultfinding and unbridled ambition made him, just then, a potentially disruptive leader. Among the other corps commanders, Porter and Franklin were notably McClellan’s men, and Sumner was notably unsuited for high command. Lincoln recognized that at this moment—unrest and worse reported in the officer corps, the supposed conspiracy disclosed by Major Key—Ambrose Burnside might be the best antidote for whatever poisons infected the Potomac army’s high command. For Henry Halleck, replacing McClellan “became a matter of absolute necessity. In a few weeks more he would have broken down the government.” Gideon Welles reflected the administration’s wait-and-see attitude: “Burnside will try to do well—is patriotic and amiable, and had he greater power and grasp would make an acceptable if not a great General. . . . We shall see what Burnside can do and how he will be seconded by other generals and the War Department.”

McClellan told his wife, “Poor Burn feels dreadfully, almost crazy” about taking the command. In the same vein, he wrote in a note to Mrs. Burnside that her husband “is as sorry to assume command as I am to give it up. Much more so.” Burnside’s reluctance hardly generated confidence among his lieutenants. George Meade heard from McClellan that at first “B. refused to take the command, said it would ruin the army & the country & he would not be an agent in any such work.” In Otis Howard’s opinion, “I should feel safer with McClellan to finish what he had planned & was executing so well. . . . I fear we hav’nt a better man.” To Alpheus Williams, “Burnside is a most agreeable, companionable gentleman and a good officer, but he is not regarded by officers who know him best as equal to McClellan in any respect.” Baldy Smith hoped Burnside would accept advice from those (Smith in particular) who “had his interests at heart.” Darius Couch asserted, in the smug comfort of hindsight, “We did not think that he had the military ability to command the Army of the Potomac.” But William Franklin saw the need to tamp down a potentially volatile transfer of power. He told his wife, “The feeling of the Army is excessive indignation. Every one likes Burnside, however, and I think that he is the only one who could have been chosen with whom things would have gone on so quietly.”

Burnside’s approach to high command was a sharp contrast to the imperial trappings of the Young Napoleon. The new commanding general was a large man of thirty-eight years, with luxuriant muttonchop whiskers—the model for sideburns—and an unpretentious manner. Daniel R. Larned of his staff told his sister, “I wish you could see the General commanding the Army of the Potomac footing it into camp without any orderlies—without his shoulder straps, belt or sword.” His tent, unlike McClellan’s, “is full all the time, & it is as informal as you please.” A guard at headquarters wrote his parents, “Old B. came out of his tent at 2 1/2 o’clock this morning in his shirt & warmed his butt at the fire before his quarters, he is a jolly bugger & will joke with a private as quick as an officer.” But Burnside took his new responsibilities, however unwelcome, very seriously. “He is working night & day . . . ,” Larned wrote. “He has slept but little and is most arduous in his labors and does not spare himself even for the common necessities of health.”

Burnside was granted little time for reflection. With the dispatch assigning him the command came one from General Halleck ordering him to “report the position of your troops, and what you purpose doing with them.” He was prompt to submit a plan of campaign—a plan in debt to McClellan’s thinking on the matter.

In starting across the Potomac on October 26, 1862 McClellan had asked Herman Haupt, superintendent of military railroads, for a report on the lines needed to supply an advance into Virginia—the Manassas Gap and the Orange & Alexandria. He asked about the wharves at Aquia Landing, on the lower Potomac, and about the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac from Aquia to Falmouth, across the Rappahannock from Fredericksburg, and about “repairing that road in season to use it for the purposes of this campaign.”

Haupt reported the Manassas Gap operable but limited in capacity. The Orange & Alexandria would have to meet the army’s immediate needs, he said. Restoring port facilities at Aquia Landing and the R. F. & P. to Falmouth (to Haupt’s disgust, both had been unnecessarily left in ruins by Burnside in evacuating the area in September) received a priority go-ahead. Haupt’s verdict: to support an advance for any distance beyond Warrenton, the O. & A. would be stretched beyond its capacity to supply an army of 100,000 men; “the Orange & Alexandria Railroad alone will be a very insecure reliance.”

Beyond the operational limits of the O. & A., there was the threat of raids on the line by John Singleton Mosby’s guerrilla band, and the greater threat by Jeb Stuart, whose most recent “ride around McClellan” was a raw memory in the Potomac army. McClellan’s interest in Aquia Landing and the Aquia–Falmouth rail line decided him, on November 6, to order chief engineer James C. Duane to shift the army’s bridge train from the Potomac crossing to Washington for potential use in bridging the Rappahannock—indicating that the Young Napoleon was considering a new road to Richmond by way of Fredericksburg. Burnside testified that before the change of command he suggested the Fredericksburg route to McClellan, and McClellan “partially agreed with me.” Staff man Daniel Larned remarked that Burnside inherited “a campaign planned & begun by another person & carried on, not as the General would have done perhaps, had he begun it.”

On November 9 Burnside submitted his plan of campaign. He would open with a feint toward the Rebels at Culpeper, then turn southeast and “make a rapid move of the whole force to Fredericksburg, with a view to a movement upon Richmond from that point.” In rejecting an advance astride the Orange & Alexandria, he argued that the enemy would simply fall back along his communications, drawing the Federals farther and farther from their base along a vulnerable, ever-lengthening supply line. But by seizing Fredericksburg the Potomac army would be on the shortest, most direct overland route to Richmond while always staying between the enemy and Washington.

Burnside’s plan rested on three assumptions. First, the Federals would gain a march or two on Lee, reach Falmouth and cross the Rappahannock on pontoon bridges laid in timely fashion, and seize lightly guarded Fredericksburg. Second, Herman Haupt’s construction crews would repair the Richmond, Fredericksburg & Potomac to Falmouth, rebuild the rail bridge across the river, then repair the line behind the advancing Potomac army as fast as the Rebels wrecked it. Third, the R. F. & P. would be supplied from the restored Aquia Landing wharfs and by additional waterborne stores along the way. Granted these assumptions and these circumstances, it was a perfectly sound plan. The administration, wrote Burnside, “will readily comprehend the embarrassments which surround me in taking command of this army at this place and at this season of the year.” Nevertheless, “I will endeavor, with all my ability, to bring this campaign to a successful issue.”

Halleck met with Burnside at Warrenton on November 12, bringing with him railroad man Haupt and Quartermaster Montgomery Meigs. By Burnside’s account, there was a debate. Halleck was “strongly in favor” of continuing the march toward Culpeper and beyond, while “my own plan was as strongly adhered to by me.” This was a revived Henry Halleck, shed at last of insolent McClellan and looking to oversee his successor. The general-in-chief spoke for Lincoln’s “inside track” to Richmond, but thanks to McClellan’s modest pace the Rebels had blocked the inside track, ending that race before it began. Haupt supported Burnside’s Fredericksburg plan, stressing the grave difficulties of supporting the Potomac army entirely by means of the Orange & Alexandria. (He hardly needed to remind his listeners of the O. & A.’s fate just 25 miles from Washington during Pope’s campaign.) Furthermore, supplying and supporting the army by water and rail from Aquia Landing would greatly simplify Quartermaster Meigs’s task.

An alternative plan—the duplicitous Halleck afterward described it (falsely) as the plan he and Lincoln approved—was for the army to continue southward, ford the upper reaches of the Rappahannock and Rapidan rivers, and reach Fredericksburg via the south bank of the Rappahannock. While this eliminated the risks of forcing a river crossing at Fredericksburg, it relied on the unreliable O. & A., and ran its own risks of being attacked in flank or rear by the Rebels. Burnside rejected this plan as rife with the unexpected, notably so for a new commanding general in his first campaign.

Halleck, characteristically, would not make a decision, saying only that he would take the matter to the president. Before he left, Burnside explained that McClellan’s chief engineer James Duane had already, on November 6, ordered the army’s bridge train moved from the Potomac crossing at Berlin, Maryland, to Washington for use in the new campaign. He wanted Halleck to apply his authority to directing the bridge train at Washington to meet the army on the Rappahannock—once the army marched it would be out of telegraphic communication until it reached Falmouth. On the evening of November 12 Halleck sent a telegram from Warrenton to Brigadier General Daniel P. Woodbury, commanding the engineer brigade at Washington, telling him to order the pontoons and bridge materials to Aquia Creek. He gave Woodbury no details of the purpose of the order nor any timetable nor any priority.

On his return to the capital, Halleck showed Lincoln Burnside’s plan and the arguments regarding it, and the president determined to give his new general his head. Halleck telegraphed Burnside on November 14, “The President has just assented to your plan. He thinks it will succeed, if you move very rapidly; otherwise not.” The next day Burnside set the Army of the Potomac on the march to Falmouth. “I think the Army has got over the depression caused by McClellan’s removal and it is in good heart for anything,” wrote Lieutenant Henry Ropes, 20th Massachusetts, “but in case of serious reverse, there would be a great want of confidence.”

Burnside reorganized the army for the new campaign. He formalized the three-wing structure McClellan had utilized for the march into Maryland, calling them grand divisions and giving them two corps each. He did this to simplify the exercise of command, but also to settle the matter of what to do with Edwin Sumner. McClellan’s attempt to angle Sumner off into a departmental posting had failed, and now he was back from leave, determined not to give away any of his standing. To return Sumner to the Second Corps would bump a string of generals down the command ladder. Giving Sumner the Right Grand Division solved the problem. The Center Grand Division went to Hooker, recovered from his Antietam wound. Fighting Joe was no favorite of Burnside’s, but he had seniority and was a newspaper hero for Antietam and could hardly be ignored. William Franklin, with seniority and on good terms with Burnside, was Left Grand Division commander. Being new to the Potomac army, Burnside let seniority be his guide in changes and filling posts.

Sumner’s Right Grand Division comprised the Second and Ninth Corps. Couch led the Second, Sumner’s old command, with division heads William H. French, Winfield Hancock (replacing the dead Israel Richardson), and Otis Howard (replacing the wounded John Sedgwick). The Ninth Corps, once Burnside’s, then Cox’s, now Orlando B. Willcox’s, had divisions under William W. Burns, Samuel D. Sturgis, and George W. Getty (replacing the dead Isaac Rodman).

Joe Hooker’s Center Grand Division contained the Third and Fifth Corps. The Third, Sam Heintzelman’s since its founding, was posted in Washington during the Maryland campaign and largely revamped. Heintzelman was shifted to departmental command and replaced by George Stoneman, McClellan’s onetime chief of cavalry. Phil Kearny’s old division went to David Birney and Hooker’s old division to political general Dan Sickles. Stoneman’s third division was new, two brigades under Amiel W. Whipple, West Point 1841, a topographical engineer. Fitz John Porter’s Fifth Corps, untested at Antietam, had a new commander, Daniel Butterfield. Butterfield had started in Robert Patterson’s old Army of the Shenandoah and fought his brigade with distinction at Gaines’s Mill. His three divisions were led by Charles Griffin, replacing the transferred George Morell; by George Sykes with his regulars; and by Andrew Humphreys with his rookies.

On learning of McClellan’s dismissal, Fitz John Porter wrote New York World editor Marble, “You may soon expect to hear my head is lopped.” He added, “My opinion of it [Pope’s campaign] predicting disaster is in their possession and brought up against me as proof of intention to cause disaster.” He predicted his fate. The order relieving McClellan also relieved Porter from the Fifth Corps. On November 25 army headquarters announced a general court-martial convened “for the trial of Maj. Gen. Fitz John Porter, U.S. Volunteers.” Porter would be charged with disobeying orders and misbehavior before the enemy at Second Bull Run. It seemed that John Pope had his revenge, at least on Porter; Pope’s charges against William Franklin and Charles Griffin were dropped. In his diary David Strother, whose connection with Porter dated back to Patterson’s Army of the Shenandoah, blamed Porter for McClellan’s downfall: “Fitz John Porter with his elegant address and insinuating plausibility, technical power, and total want of judgment has been the evil genius, has ruined him as he did Patterson.” Following McClellan into military exile, Porter awaited trial.

William Franklin’s Left Grand Division contained the First and Sixth Corps. The three divisions of John Reynolds’s First Corps were commanded by Abner Doubleday, George Meade, and John Gibbon (replacing the injured James Ricketts). The Sixth Corps went to Baldy Smith after Franklin’s advancement. Smith’s three divisions were newly led: W.T.H. Brooks replaced Henry Slocum, promoted to command the Twelfth Corps; John Newton replaced Darius Couch, promoted to command the Second Corps; and Albion P. Howe, from the old Fourth Corps, took Baldy Smith’s division.

Alfred Pleasonton continued to head the army’s mounted arm, comprising the brigades of John F. Farnsworth, David M. Gregg, and William W. Averell. Henry Hunt, now brigadier general, remained chief of artillery. Franz Sigel’s Eleventh Corps (First Corps in the old Army of Virginia) was designated a general reserve for the Potomac army, and when Burnside set off for Falmouth, Sigel covered Washington. Henry Slocum’s Twelfth Corps (Second Corps, Army of Virginia) remained at Harper’s Ferry to guard the Potomac line.

Ambrose Burnside’s army was in all but its commander’s name still George McClellan’s army. Halleck granted Burnside full powers to post or remove any officers except corps commanders (the president’s prerogative), but his only real change was the grand divisions format—and that copied from McClellan. Most generals were McClellan’s generals. In addition to the new grand division commanders, all six corps commanders were new, as were twelve of the eighteen divisional commanders and thirty-five of the fifty-one brigade commanders. Burnside’s experience in battle with his lieutenants was minimal—limited at South Mountain to Jesse Reno, who was killed, and to Joe Hooker, who marched to his own drum; limited at Antietam to Jacob Cox, now gone from the army. In the evolving campaign Burnside would have to forge relationships with his generals, and they with him, on the fly. He confided to Franklin that the “awful responsibility” of command weighed on him and left him sleepless. “I pitied Burnside exceedingly,” Franklin told his wife.

McClellan left the army short-staffed, taking away with him nearly all the headquarters staff; he needed them, he said, to help prepare the report of his command tenure. (Not missed among the departed was the bumbling Allan Pinkerton.) Burnside had capable John G. Parke as chief of staff, but his administrative grip on the army was not very sure.

The moment the Army of the Potomac crossed the Potomac it began to lay a hard hand on the Virginia countryside. John Pope’s general order permitting his army to forage freely in enemy country had migrated into McClellan’s army (now Burnside’s army) and been widely accepted there. “The people here are all rebels,” a Massachusetts soldier told his wife. “We have had a grand time, killing and eating their sheep, cattle and poultry. One farmer here lost nearly three hundred sheep the first night our boys encamped.” In the case of a Union man’s property a guard would be detailed to protect his goods. Otherwise, “Our officers say nothing if we take a rebel’s turkeys, hens, or sheep to eat; they like their share.”

Marsena Patrick, the new provost marshal, had witnessed the demoralizing effect of Pope’s foraging order on the Army of Virginia and he dreaded its spread to the supposedly better-behaved Army of the Potomac. “I am distressed to death with the plundering & marauding,” he told his diary. “I am sending out detachments in all directions & hope to capture some of the villains engaged in these operations.” Cavalry was the worst, “stealing, ravaging, burning, robbing. . . .” The conduct of William Averell’s cavalry brigade “makes one’s blood boil . . . little better than fiends in human shape.”

On November 14, the day before the army was to start for Falmouth, General Burnside, “feeling uneasy,” had his chief engineer C. B. Comstock telegraph the engineer brigade at Washington to be sure the bridge train sent to the capital from Berlin by Duane’s November 6 order was ready to march. Burnside also called for a second bridge train to be “mounted and horsed as soon as possible” to follow the first train.

Daniel Woodbury, head of the engineer brigade, replied the same day that pontoons were only just then starting to arrive from Berlin. He said it would be, at best, two or three days before all the components of a train could be gathered and mounted and ready to march. He added that Duane’s November 6 order to send the bridging materials to Washington was only received at Berlin on the afternoon of November 12. He offered no explanation why a telegraphed order had required six days to reach its destination. With that, the first prerequisite of Burnside’s campaign—steal a march on the Rebels and bridge the Rappahannock and seize Fredericksburg in one thrust—was endangered before it even began.

Pinning responsibility for the six-day delay proved elusive. As of November 6 McClellan’s advance had broken communication with Berlin, and Captain Duane sent the telegraphed order via Washington . . . where the War Department telegraph office, by inscrutable logic, forwarded the order to Berlin by mail, aboard a leisurely packet on the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal. (The Washington–Berlin telegraph line was fully functioning.) This blunder ought to have been caught—except that in the upheaval of McClellan’s dismissal Duane failed to follow up when Berlin did not acknowledge his order. Forgetful Duane (or indifferent Duane; it was he at Antietam who misrepresented the ford on Burnside’s front) then departed the Potomac army along with McClellan’s staff. Burnside trusted Halleck to oversee Woodbury’s engineer brigade at the capital, supposing he “fully covered the case.” A trust misplaced. “I had advised against the Fredericksburg base from the beginning,” Halleck would say, and he lifted not a finger for its support.

Burnside told Woodbury to send the second bridge train by water to Aquia Landing, and went ahead as planned. On November 15 Sumner’s Right Grand Division started for Falmouth. Bull Sumner covered the 40 miles at a fast pace and reached Falmouth on the 17th, the rest of the army not far behind, with Burnside himself arriving on the 19th. Where, he asked, was the bridge train?

A bridge train might have forty pontoons, each mounted on a specially adapted wagon that also carried the connecting timbers, or balks; fifteen other adapted wagons for the cross planks, or chesses; and additional wagons with cables, gear, and tools—perhaps sixty wagons all told, with six-horse teams. At Berlin Major Ira Spaulding of the engineers hastily improvised after he finally received his orders on November 12. He took up the Potomac bridges, had the heavy pontoons towed down the C. & O. Canal to Washington, and sent as many of the lightened wagons overland as he had teams to haul them. In the capital Major Spaulding took up his task anew, laboring with Meigs’s quartermasters to assemble and mount a train for the overland march. It was a slow process, requiring on short notice 270 fresh horses to be collected, harnessed, and shoed.

General Woodbury would claim that before November 14 “no one informed me that the success of any important movement depended in the slightest degree upon a pontoon train to leave Washington by land.” Consequently, surveying the unpromising situation, he went to Halleck and proposed a five-day delay in Burnside’s advance. This would put the bridge train back on schedule with the army. Burnside’s march could be halted with no harm to the plan. By Woodbury’s testimony, Old Brains “replied that he would do nothing to delay for an instant the advance of the army upon Richmond.” His proposal, said Woodbury, would not cause delay but prevent it. But Halleck’s witless response stood. Burnside was not informed or consulted. His march proceeded on the assumption the bridge train would not be unduly delayed.